On a trip to Mechelen, Derek Blyth discovers lost mediaeval rivers, Beethoven’s Flemish roots and the world’s oldest carillon school.

Five hundred and thirty-six. Deep breath. Five hundred and thirty-seven. Almost there. Five hundred and thirty-eight. And I’ve made it to the top of Mechelen’s tower. When the weather is right, they say, you can see all the way to the Atomium in Brussels.

The impressive tower of St Rumbold's Cathedral.

The impressive tower of St Rumbold's Cathedral.© Visit Mechelen

When it was begun in about 1452, Mechelen’s tower was intended to be the world’s tallest structure. It would have reached an astonishing 167 metres, according to the original plan, drawn up by Andries Keldermans the Elder. His son Anthonis took over the construction in 1481, and grandson Rombout worked on the project from 1488 until the 1520s. But then the work was inexplicably halted.

It might have been a lack of funds, political unrest, or some other reason. It must have hurt local pride to see the half-finished tower, just 97 metres high, a long way short of Antwerp Cathedral’s 123 metres. Yet the unfinished construction still impressed Vauban, Louis XIV’s military engineer, who ranked it as the eighth wonder of the world.

The tower of St Rumbold's Cathedral dominates Mechelen.

The tower of St Rumbold's Cathedral dominates Mechelen.© Visit Mechelen

Five centuries on, the tower still dominates Mechelen. It has two carillons, each with 49 bells, that ring out across the city every hour. Sometimes the city carillonneur Eddy Mariën will climb all those steps to the little room up in the tower to perform a concert. As you wander through the streets, you might hear him play a traditional folk melody, or a Chopin nocturne, or an Abba song.

Carillonneur at work

Carillonneur at work© City of Mechelen

The city has been a centre for carillon playing since the first concert was performed in 1892. The world’s first carillon school was established in Mechelen in 1922 by the city carillonneur Jef Denyn. It was the only place in the world where the difficult art of carillon playing was taught until a Dutch school was established in 1953. The Mechelen school, which recently moved into a former priory, still attracts students from all over the world.

Back down at street level, I took a look inside the Cathedral. Begun in about 1200, it is dedicated to Saint Rombout (or Rumbold, if you prefer). Like many saints, his life is rather sketchy. He may have been born in Scotland. Or perhaps not. He is believed to have lived in the sixth century (or it might have been the seventh, or the eighth, according to Wikipedia). He is said to have been murdered by two men after he accused them of sin. It seems quite a thin life story for a saint who has given his name to Belgium’s most important cathedral.

Inside the St Rumbold's Cathedral

Inside the St Rumbold's Cathedral© Visit Mechelen

The interior is a stunning example of Gothic architecture with a booming organ that shakes the dusty statues. It has a dramatic carved pulpit and enough paintings to fill a decent museum. The art collection includes a series of damaged oil paintings that illustrate episodes in the life of Saint Rombout. These carefully-preserved works are among the great masterpieces of Flemish art.

The Cathedral has ruled over Mechelen for centuries. But the church has in recent years been rocked by endless scandals. It no longer plays a role in many people’s lives. Its diminished status used to be neatly symbolised by a trendy burger restaurant named Il Cardinale that opened opposite the Cathedral. The interior was decorated with hundreds of ironic statues of the Virgin Mary while the menu listed burgers with cheeky names like Mary Had a Little Lamb and Baby Jesus.

I can remember when Mechelen was a sleepy provincial city between Brussels and Antwerp. The locals had a reputation for being slightly stupid. It went back to a story, possibly invented, when someone thought the Cathedral tower was on fire. It was in fact the moon shining through the tracery. It led to a popular insult. Maneblussers – the idiots who tried to put out the moon.

The nickname of the inhabitants of Mechelen is the Maneblussers.

The nickname of the inhabitants of Mechelen is the Maneblussers.© City of Mechelen

Mechelen didn’t seem to have the style of Antwerp or the progressive spirit of Ghent. It was a dull, stuffy place. The mood struck you the moment you stepped off the train. The station was old and grimy. The main street into town was lined with furniture stores where they sold heavy oak tables and stuffy English sofas.

But then it changed. The transformation, most people agree, began with the election of Bart Somers as mayor. That was back in 2000. He took charge of this rather grey city of 86,000 people with roots in 120 different countries. His plan from the beginning, long before the refugee crisis, was to integrate everyone. ‘What counts is not your origin, but your future,’ he argued.

Bart Somers was elected Best Mayor of the World 2016 for transforming ‘the rather neglected city of Mechelen into one of Belgium’s most attractive places’.

Bart Somers was elected Best Mayor of the World 2016 for transforming ‘the rather neglected city of Mechelen into one of Belgium’s most attractive places’.© Flanders Chancellery and Foreign Office

He surprised some with his tough policies on crime and other urban problems. He wrote a pamphlet with the title ‘Iedereen Burgemeester!’ – ‘Everyone for Mayor’. He argued that citizens had to accept responsibility for their city, instead of just complaining. It worked. Mechelen was praised as a successful model for urban regeneration. Somers also attracted attention for his plan to integrate the city’s refugees by launching a ‘buddy’ programme that matched new arrivals with locals. In 2016, he was awarded the World Mayor Prize for transforming ‘the rather neglected city of Mechelen into one of Belgium’s most attractive places’ as well as making it ‘a role model for integration.’ Three years later, the Financial Times listed Mechelen as one of the top ten micro-European cities of the future. Something was happening in sleepy Mechelen. I wanted to find out more.

As I walked through the streets, I noticed signs announcing new traffic regulations. It meant cyclists and pedestrians had priority over cars on every street. Mechelen had become one of the first Flemish cities to adopt a radical plan to deter cars.

It made a huge difference. I turned into Onze-Lieve-Vrouwestraat, a lively street with concept stores, food shops and the independent bookstore De Zondvloed. The street seemed lively, even on a Sunday morning. People were walking, or cycling or sitting on benches. Children were playing in the streets. The slow traffic had an impact on the way you experience the city. You walk more slowly, notice architectural details, hear the carillon bells.

The Dijlepad takes you past ancient houses, abandoned factories and overgrown gardens.

The Dijlepad takes you past ancient houses, abandoned factories and overgrown gardens.© City of Mechelen

I turned down a narrow alley that led down to the Dijle waterfront. Here was another new urban project. A wooden walkway, the Dijlepad, has been constructed along a stretch of the river formerly only accessible by boat. The route takes you past ancient houses, abandoned factories and overgrown gardens. Several new apartment buildings have already sprung up in this forgotten location with terraces overlooking the river. It could almost be Copenhagen.

The waterfront trail led to the Zoutwerf, a former harbour where an impressive renaissance house was built in 1530 for the guild of fishermen. The walkway then passed under a low bridge to end at the Lamot cultural centre, located in a former brewery.

On the Zoutwerf an impressive renaissance house was built in 1530 for the guild of fishermen.

On the Zoutwerf an impressive renaissance house was built in 1530 for the guild of fishermen.© City of Mechelen

I was looking for Van Beethovenstraat, formerly known as Steenstraat. The name is a reminder that Ludwig van Beethoven’s grandparents lived in Mechelen. Not that the composer ever visited Mechelen. He was only three when his grandfather died. And yet his roots are in Flanders, which is why his name uses the Flemish van, not the German von.

Is this important? you might wonder. It is to some people. In 1993, the Japanese journalist Nagayo Taniguchi travelled to Mechelen to investigate the elusive Van Beethoven connection. He went through the phone book looking for Beethovens and visited the city archives. Here he found the baptism certificate of Ludovicus Van Beethoven, the composer’s grandfather, who sang in Saint Rombout’s Cathedral, and later settled in Bonn. The journalist asked in a cafe if the waiter knew any Beethovens, and, believe it or not, the man said he had gone to school with a boy called Van Beethoven. A phone call later, and the journalist was introduced to no less than ten Van Beethovens living in a village outside Mechelen.

A statue of the young Ludwig van Beethoven is a reminder that his grandparents lived in Mechelen.

A statue of the young Ludwig van Beethoven is a reminder that his grandparents lived in Mechelen.© City of Mechelen

The city is proud to celebrate its connection with the great composer. It has put up a curious statue of the young Ludwig looking up at his grandfather. And there is a new (and controversial) Beethoven bridge next to the Lamot centre. The Japanese journalist even discovered a nightclub called Disco Beethoven but I think it might have closed.

I walked across the Beethovenbrug to reach the former fish market square. It’s a lively spot on the waterfront surrounded by cafes and restaurants. I dived into De Gouden Vis, an old brown cafe with wooden floors, a romantic conservatory and a tiny hidden terrace at the back overlooking the water. It seemed like the perfect spot to try the local Gouden Carolus beer.

The Hof van Busleyden Museum occupies a flamboyant palace where the humanist lawyer Hieronymus van Busleyden lived in the early 16th century.

The Hof van Busleyden Museum occupies a flamboyant palace where the humanist lawyer Hieronymus van Busleyden lived in the early 16th century.© City of Mechelen

I had been planning to visit the Hof van Busleyden Museum. The city museum occupies a flamboyant palace where the humanist lawyer Hieronymus van Busleyden lived in the early 16th century. Built in Late Gothic style by Rombout Keldermans, the palace became a centre of Northern Renaissance culture visited by Erasmus and Thomas More. In 1938, it was turned into a local history museum. When I first visited, it contained a dark and dusty collection of relics. Some old paintings of Maneblussers stick in my mind. And there was an intimate dining room decorated with Renaissance murals, including a scene representing Belshazzar’s Feast.

The museum was renovated a few years ago. It told the story of Mechelen through religious art, portraits and music. The paintings of the Maneblussers disappeared. Then the museum unexpectedly closed again for essential renovation work. It is due to open again in autumn 2023.

The Hof van Busleyden Museum tells the story of Mechelen through religious art, portraits and music.

The Hof van Busleyden Museum tells the story of Mechelen through religious art, portraits and music.© City of Mechelen

Van Busleyden settled here during a brilliant period in Mechelen’s history. Its golden age began in 1474 when Charles the Bold installes the Grote Raad (Great Council) in Mechelen. This body was the supreme court of the Low Countries, turning Mechelen into the Strasbourg of the 15th century. The city attracted lawyers and councillors, but also artists and musicians.

Mechelen received another boost after Charles the Bold died, and his English widow Margaret of York moved into a palace in Mechelen. She had no children, but raised several step-grandchildren here, including the boy who became Philip the Fair and the girl who grew to become Margaret of Austria.

After Margaret became regent of the Low Countries, she moved the court from Brussels to Mechelen, and built herself a palace across the road from the building where she had spent her childhood. The move turned this modest city into the capital of the Low Countries and a centre of northern Renaissance culture.

Margaret of Austria’s former palace is now a law court.

Margaret of Austria’s former palace is now a law court.© City of Mechelen

I set off to see what had survived from Mechelen’s finest years. Some local school students were waiting at a bus stop on the little square outside Margaret of York’s former palace (now the city theatre, opposite the palace of Margaret of Austria). It was difficult to believe this neighbourhood was once teeming with European nobles, artists and lawyers. I took a look inside the renaissance courtyard on the opposite side of the street where Margaret of Austria’s guests would have arrived, among them Albrecht Dürer, Erasmus and Bernard van Orley. Her palace is now a law court. The only people allowed inside are lawyers and defendants.

Margaret of Austria (1480-1530), painted by Bernard van Orley in 1518

Margaret of Austria (1480-1530), painted by Bernard van Orley in 1518© Wikipedia

Margaret of Austria married three times, but each of her husbands died, and she remained childless, writing sad poetry to console herself. She went on to surround herself with children from aristocratic families, including the 12-year-old Anne Boleyn who was sent by her diplomat father in 1513 to serve as one of Margaret’s maids of honour. Anne spent a year in Mechelen where she learned the art of dancing, hunting and courtly love. Then she made the fatal decision to marry Henry VIII.

Mechelen lost its role as capital of the Low Countries when Margaret died in 1530. The capital moved to Brussels and the city went into a slow decline. The wealthy lawyers and aristocrats moved away and their palaces were abandoned. But the city still has impressive buildings dating from Mechelen’s brief period of greatness. Some are Late Gothic. Others have Early Renaissance details.

The most striking buildings are three brightly-painted houses on the Haverwerf. They are covered with curious figures – you might spot Adam and Eve on one house, or a row of carved devils on its neighbour. They suggest Mechelen must have been a bright, intelligent place.

Three brightly-painted houses on the Haverwerf.

Three brightly-painted houses on the Haverwerf.© City of Mechelen

But the city changed after Philip II of Spain turned it into a bastion of Catholicism. He appointed an archbishop, Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, who moved into Margaret of Austria’s empty palace. Mechelen became engulfed in the rule of terror imposed by Philip II of Spain. Its tolerant renaissance period came to a brutal end.

The quiet, religious backwater began to recover in the early 19th century when the first railway line in Continental Europe ran from Brussels to Mechelen. The city developed into an industrial hub with railway workshops, breweries and furniture factories. But its industrial prosperity didn’t last. The factories started to close and the unemployment rate went up. Until recently, Mechelen seemed to face a grim future. But now there are ambitious plans that include the construction of a new railway hub and several new hotels.

The first railway line in Continental Europe ran from Brussels to Mechelen.

The first railway line in Continental Europe ran from Brussels to Mechelen.© City of Mechelen

It used to be difficult to find a room for the night in Mechelen. It wasn’t a destination for tourists. But now there are stunning places to stay in unusual buildings. The Van der Valk Hotel opened in 2019 in a renovated former Art Deco swimming pool where locals once learned to swim. The original changing rooms are still in place, but the pool has been turned into an ornamental pond.

The country’s first brewery hotel is another new initiative. Located next to Het Anker brewery, where the strong dark ale Gouden Carolus is brewed, the hotel looks out on the courtyard where beer trucks pull up. Guests can watch the brewing process from the breakfast room and drink a beer in the brewery’s nostalgic tavern.

Both seemed tempting. But I had decided to book a room in a 19th-century Franciscan church turned into a stylish hotel. Its 79 unique rooms incorporate original details such as Neo-Gothic arches, stone columns and stained-glass windows. An almighty sin, some might argue.

A 19th-century Franciscan church turned into a stylish hotel.

A 19th-century Franciscan church turned into a stylish hotel.© Brussels Times

In 2015, the Belgian singer Stromae booked the entire hotel for a secret wedding. He married his stylist Coralie Barbier in a simple ceremony inside the former church. Room 528, where the couple spent the night, is a beautiful space with a Neo-Gothic vaulted roof and stained-glass windows. It has become a favourite with social media influencers and romantic couples.

***

The next morning, I went to Kazerne Dossin. It’s not an easy place to visit. More than 25,000 Jews and several hundred Roma were held in Dossin army barracks on the edge of Mechelen before they were put on trains to Auschwitz and other camps. For many years, Belgians were hardly aware of this dark period in the country’s history. But that changed in 2012 with the opening of Kazerne Dossin.

Kazerne Dossin tells the history of the Holocaust.

Kazerne Dossin tells the history of the Holocaust.© © Flanders Chancellery and Foreign Office

The museum occupies a sober modern building designed by Antwerp architects AWG led by Bob van Reeth. Its aim to tell the almost unbearable history of the Holocaust using photographs, documents, video interviews and historic objects. The first display to confront visitors is an enormous photo wall that rises through four floors. It is covered with 25,500 official passport photos (or silhouettes, where no photo has been found) to represent the people who passed through the barracks.

25,490 Jews and 353 Roma were deported from the Dossin barracks on 28 train transports to Auschwitz-Birkenau between 1942 and 1944. Today the old military base is a site of reflection and remembrance, a Memorial.

25,490 Jews and 353 Roma were deported from the Dossin barracks on 28 train transports to Auschwitz-Birkenau between 1942 and 1944. Today the old military base is a site of reflection and remembrance, a Memorial.© Kazerne Dossin

A large section of the museum is given over to the 28 train convoys that left from Mechelen, each carrying more than 1,000 people. In a series of small rooms, the details of each convoy are listed. How many were taken. How many survived. The figures are brutal. And, to add to the pain, there are photographs of a few of the victims. Not passport photographs this time, but framed family snapshots from before the war. Two smiling girls. A mother pushing a pram. A couple on a café terrace.

The museum has carefully pieced together a number of individual stories using small objects that somehow survived the war. They include drawings, children’s toys and confiscated possessions. The museum has also gathered a collection of scribbled letters and postcards that victims threw from the trains as they were taken off to an unknown destination (Holland, they were often told). The letters carry desperate final messages for relatives back in Belgium. The last post, the museum calls them.

Displayed in a glass case, two small objects tell a rare story of heroism. A fake emergency lantern and a small pistol were used by three young students to stop the Transport XX train carrying 1,600 Jews to Auschwitz. More than 200 people escaped, including Simon Gronowski, who now talks to Belgian schools about his experience.

There is a second, more reflective, place across the road. The Memorial occupies several rooms in the former barracks where people were held. Opened in 1995, and given a total makeover in 2019, it is a quiet, reflective place compared to the museum. The Museum analyses the history, but the Memorial tells you about the victims.

The first room you enter is a dark, unsettling space with victims’ haunted eyes seen through small slits. Then comes a more upbeat space with pre-war music playing in the background. The walls covered with photographs of Jews celebrating weddings, walking in the sun, eating ice cream. The mood turns darker in the next room, which is furnished with two desks and a typewriter. You hear the rattle of the keys as names slowly emerge on a ledger. Lining the room, glass cases are crammed with old passports, documents and photographs.

Then comes a room where you see simple drawings made by the inmates. Many are by Irène Spicker, a German Jewish artist who passed the time drawing scenes in the barracks. She sketched the view through a window, a glimpse of sky, a series of children’s portraits.

Down in the basement, a dark brick cellar is filled with photographs of children who were held in the barracks. In 2020, a painting by Irène Spicker known as The Girl with the Red Hair and the Green Coat was hung in this space. This portrait of an anonymous girl was chosen to represent all the young people who passed through Dossin.

The final room is designed like a memorial chapel with a shape forming the Hebrew word ‘Sakhor’ (never forgotten) placed on a bed of white pebbles. The names of all 25,500 victims are slowly read out in this room. It takes more than 24 hours for every name to be spoken. I listened to a dozen or so. ‘Vos, Lisa, one year old’, was the last name I heard as I left the room.

The Memorial is definitely not a place that lifts your mood. But it does something important. It tells you about some of the people who lost their lives in the Holocaust. You see their faces. Discover their stories. It means they are not forgotten.

***

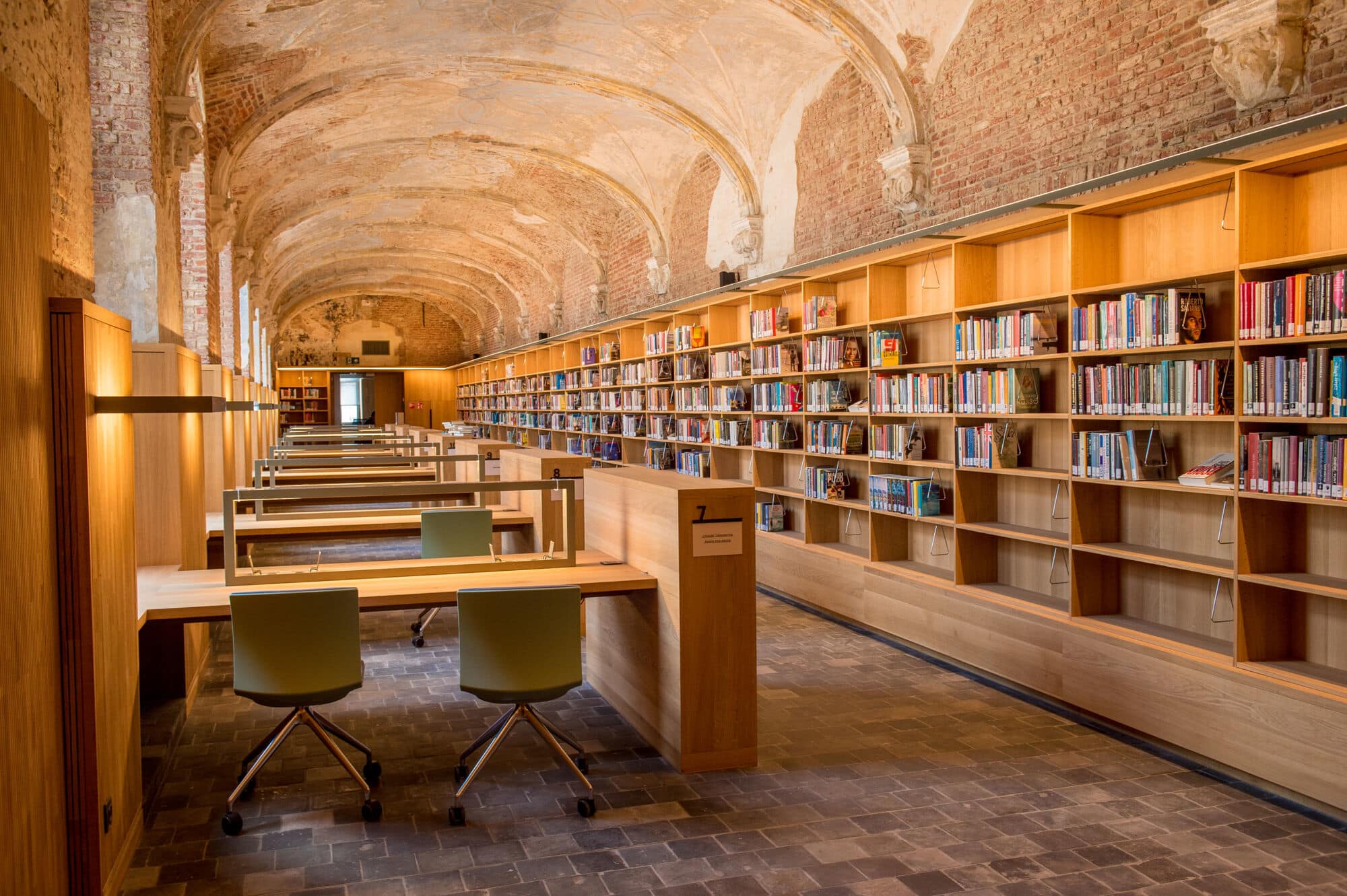

The public library is housed in an abandoned baroque monastery.

The public library is housed in an abandoned baroque monastery.© City of Mechelen

Not far from the barracks, the city has created a stunning public library inside an abandoned baroque monastery. This welcoming space (with a stylish café) reflects Mechelen’s new mood. The monastery was founded by Catholic monks fleeing the Netherlands. But it has not seen a monk in more than two centuries.

The monastery was closed down under the French occupation at the end of the 18th century. It briefly became a poor house, then a military arsenal and hospital, and finally a military barracks. The building was abandoned by the Belgian army in the 1970s, left to rot for more than 40 years, and finally rescued in 2019 by Rotterdam architect Mechthild Stuhlmacher. She reshaped the monumental building by installing polished stone floors, reading desks and a fabulous children’s library in the attic. Stuhlmacher has a way with wood, which is incorporated into the fabric to create a warm feeling. And she has preserved intriguing traces from the past, including faded wallpaper, ancient wood beams and carved gravestones.

The scope of transformation is reflected in photographs taken before the renovation, showing the abandoned ruin at a time when it was colonised by bats, buried under ivy and flooded with rainwater. It’s easy to understand that it took a budget of €25 million to renovate the ruin. There are beautiful reading rooms, meeting spaces for local groups, and quiet corners where you can sit with a novel. The result is a warm, complex building where visitors can browse the shelves, drink a coffee in the old cloister, or sit out in the garden to hear a concert.

The city is gradually uncovering a network of hidden streams (vlietjes in Dutch) that run through the city.

The city is gradually uncovering a network of hidden streams (vlietjes in Dutch) that run through the city.© City of Mechelen

On leaving the library, I came across another new initiative. The city is gradually uncovering a network of hidden streams (vlietjes in Dutch) that run through the city. So far, the project has uncovered ten stretches of water to create appealing trails through the centre (some too new to appear on Google maps). The first of the restored waterways, the Nieuwe Melaan, was created in 2007 around the walls of the art school. Another stream meanders behind the old houses in Muntstraat. The project won financial support from the EU under a plan called Water in Historic City Centres. It has been praised as a way of helping the city cope with heavy rainfall caused by the climate crisis.

I came across another impressive project in a quiet back street. The Vleeshalle, an abandoned 19th-century meat market, has been converted into a huge smaakmarkt (food market), filled with stands where you can order tapas, Vietnamese pho, croquettes or a barista coffee.

The Vleeshalle has been converted into a huge food market.

The Vleeshalle has been converted into a huge food market.© City of Mechelen

The city has also created some striking new spaces for culture including a cinema inside the Stadsfeestzaal, a former festival hall. Harder to find, the cultural centre nOna occupies a former printing works hidden away in a warren of narrow lanes.

I ended my urban ramble in the Groot Begijnhof. This quiet warren of cobbled lanes was once occupied by Beguines, a religious order of single women. The women have all died, but their neat, whitewashed houses still make this one of Mechelen’s most attractive neighbourhoods.

Not much is known about the Beguines. They were not nuns, but more like early feminists. The movement emerged during a period when unmarried women had almost no rights. Some single women chose to live in a Begijnhof, or Beguinage, in a house they owned or rented. They earned an income by nursing the sick, teaching or lace-making. The Beguines also ran a brewery within the Groot Begijnhof walls. Some locals decided to launch a Begga Festival in 2022 to celebrate these straffe madammen, or strong women.

Pope John Paul II paid a visit to Mechelen in 1985.

Pope John Paul II paid a visit to Mechelen in 1985.© City of Mechelen

As I was about to leave the Begijnhof, I noticed a curious brown sign attached to a house behind the church. It claimed (in four languages) that Pope John Paul II knocked on the door of Moreelstraat 6 during a visit to the Begijnhof in 1985. His Holiness apparently asked to use the toilet. The ‘Holy Toilet’ has since become a destination for an annual pilgrimage because of its miraculous healing powers, the sign said. Holy cow! Really?

Sadly, it’s not true. The owner of the house, who is Dutch, put up the sign as a joke. Some locals seem to have fallen for it. But then that’s not at all surprising when you remember the legend of the fire in Mechelen’s tower that turned out to be the moon.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.