Before Amsterdam made an international name for itself as a port and trading town, it became known as a place of pilgrimage in the Middle Ages. Thanks to a Eucharistic miracle.

As much as we may like to imagine that those at the top of the social and political ladders – the kings, queens, counts, and dukes, politicians, merchants and bankers – are the people who drive history onwards, it is everyday people that truly live and experience most of what happens in history, whether or not their names go in the record books.

In this episode, we imagine the extraordinary life of a farm boy from Kennemerland who, as the youngest, must venture out to find work and a life beyond his parent’s farmstead. He has benefited from the educational system set up by the Brethren of the Common Life, a lay-religious community, and is able to read, giving him an advantage in everyday life. Being the 1400s he is faithful to the church and, from a young age, determined to make a pilgrimage to the holy town of Amstelredam.

Consequence of constant war

Our lad begins his pilgrimage and must head to the village of Sloten, and there find the Heilige Weg, the Holy Way, which was a road and waterway that lead straight to Amsterdam. Its creation was demanded because of the sudden increase of pilgrim traffic into the town following a miracle. However, on his way, he falls victim to one of the near-constant risks of wandering around the Low Countries at this time.

In the 1420s Holland was embroiled in a civil war, between Lady Jacoba of Bavaria and her Hook supporters, and her uncle, Lord John of Bavaria, and his Cod faction. Our traveller is captured by some Cod soldiers, taken and interrogated. Because of his ability to read, he is able to gain the trust of his captors and is then enlisted to become a Cod soldier.

Usually, soldiers would be enlisted by being indebted to their direct lord, who was ordered to mobilise forces. Being a pilgrim would likely have protected you somewhat from being accosted, but we wanted to put a bit of drama into the story and also explore what kind of things soldiers were forced to do and go through, on behalf of the territorial ruler they were fighting for. Our character goes through war, until in 1419 the Treaty of Woudrichem allows him to leave his company and complete his pilgrimage to Amstelredam.

The Oude Kerk (Old Church) is Amsterdam’s oldest building. It was erected around 1213.

The Oude Kerk (Old Church) is Amsterdam’s oldest building. It was erected around 1213.© Wikipedia

Amstelredam in the early 15th century

Amstelredam grew out from a dam built in the 13th century at the mouth of the Amstel River. The dam’s purpose was to fortify a dike system that defended against the tides of the Zuiderzee, and to control a canal system that allowed the Amstel to irrigate the farmlands around the town before feeding out through the dam into the sea without allowing any saltwater back in.

The miracle of Amstelredam happened in 1345. It almost instantly turned the town into a holy destination for pilgrims from all around Europe. People would make a pilgrimage for various reasons; it could be a family tradition, it could be done by one’s own pious volition, but it could also be a sentence imposed on someone as penance for a crime. What this meant is that people began to descend upon Amstelredam.

The city was on the rise commercially. It had tapped into the growing superiority of the Dutch herring and ship-building industries, and was also expanding its reach further and further north, where vast quantities of grain, fur and wood could be bought cheaply and brought back to be sold in other markets. The miracle and the tradition of pilgrimage provided another pillar to the economy of the town, and provided even more opportunities for making money.

This meant that by the 1420s Amtelredam’s population had boomed to around 7000 people, and was spilling out beyond the city ramparts. Not everyone was a citizen with burgherrecht

(citizen’s rights). One could live for years, or indeed be born there and not be a citizen. Generations of a family could find no recourse for true protection from living in the city in which they were born and lived. Rich foreigners, of course, could come in and buy these rights for a small fortune.

Oldest surviving map of Amsterdam (1538) showing the city's finished medieval walls, towers and gates

Oldest surviving map of Amsterdam (1538) showing the city's finished medieval walls, towers and gatesHow the medieval town looked

Amstelredam at this time would have already felt busy, especially for a person from a rural area. It was made almost entirely from wood, at the time our story takes place. We can imagine lots of oak beams and thatch, through the cracks of which you would see smoke drifting out from the open hearths within.

Were you to walk down the street you would be struck by the dank and woody smell of these hundreds of hearths burning vast quantities of peat for warmth. Occasionally the more acrid smoke from a forge would be added to it. The street would be a muddy, clay mix, and outside the houses there would be straw thresh thrown down. The main streets were the original dikes (much as they are today) and on these you would be surrounded by all kinds of different people: poor, wealthy, religious, foreign and local, young and old, all walking around tending to their business, or just relaxing and chatting.

There would be lots of livestock being moved around, or even slaughtered on the street and sold in slabs and pieces to members of the diverse crowd. It might even be cooked on stoves people have set up on the street, so you can add the smell of burning fat and meat to the sensory image we are creating.

Beyond the sounds of a noisy crowd, you would hear the bleating of the livestock, the striking of hammers on forges, the shouting of vendors advertising their wares, and bells ringing out from churches and cloisters.

Map of Amsterdam in the Middle Ages

Map of Amsterdam in the Middle Ages© David Cenzer

The miraculous host

The earliest original source recounting the story of the miracle of Amstelredam comes from 1378, therefore 33 years after the event is supposed to have occurred. It is written by Albert I of Bavaria, the regent of Holland (father of William VI & grandfather of Jacoba of Bavaria), who recorded an account of the miracle in a letter he wrote to the newly elected Avignon Pope, Clement VII.

‘When in the city of Amsterdam in Holland, in the diocese of Utrecht someone became seriously ill, he feared he would soon die. He therefore asked to receive the last rites from the priest. The priest went to see him and when he had heard the sick man’s confession, he administered the sacrament of the Eucharist. The sick man, however, could not stop himself from throwing up; he managed to reach the fireplace and vomited into the fire. He inadvertently spewed the intact Eucharist which he had just consumed into the fire, which flared up high. But the Sacrament remained undamaged by the fire. A beautiful chapel was built on the place where the miracle took place, and in it the very same Sacrament is still reverently preserved and miracles occur daily.’

The (Eucharistic) Miracle of Amsterdam. Woodcut made in 1518 by Jacob Cornelisz (1470-1533).

The (Eucharistic) Miracle of Amsterdam. Woodcut made in 1518 by Jacob Cornelisz (1470-1533).© Wikimedia Commons

However, the miracle was recognised by Utrecht’s episcopal authorities very early on. In 1346 the auxiliary bishop of Utrecht, Nythardus, came to Amstelredam, and issued a charter granting forty days of indulgence to those who made a pilgrimage to ‘where the miracles with the Sacrament occurred’. A month later the actual bishop of Utrecht, Jan van Arkel, wrote to the town clergy about the ‘Body of the Lord’. He told them that they could hold as many processions in honour of it as they deemed necessary, keep it open to the public, held within a crystal monstrance that his vicar had blessed, and publicly proclaim the miracles that were bound to happen around it.

He also allowed them to replace the actual bread itself, given its material composition and inevitable tendency to decomposition. The bread must be kept looking fresh to bolster people’s devotion. In fact, the regulations of how good the Eucharist had to look were fairly established within the ecclesiastical order. It had to be bright white and intact—no mouldy bread. The texts of these affirmations were re-recorded in 1442.

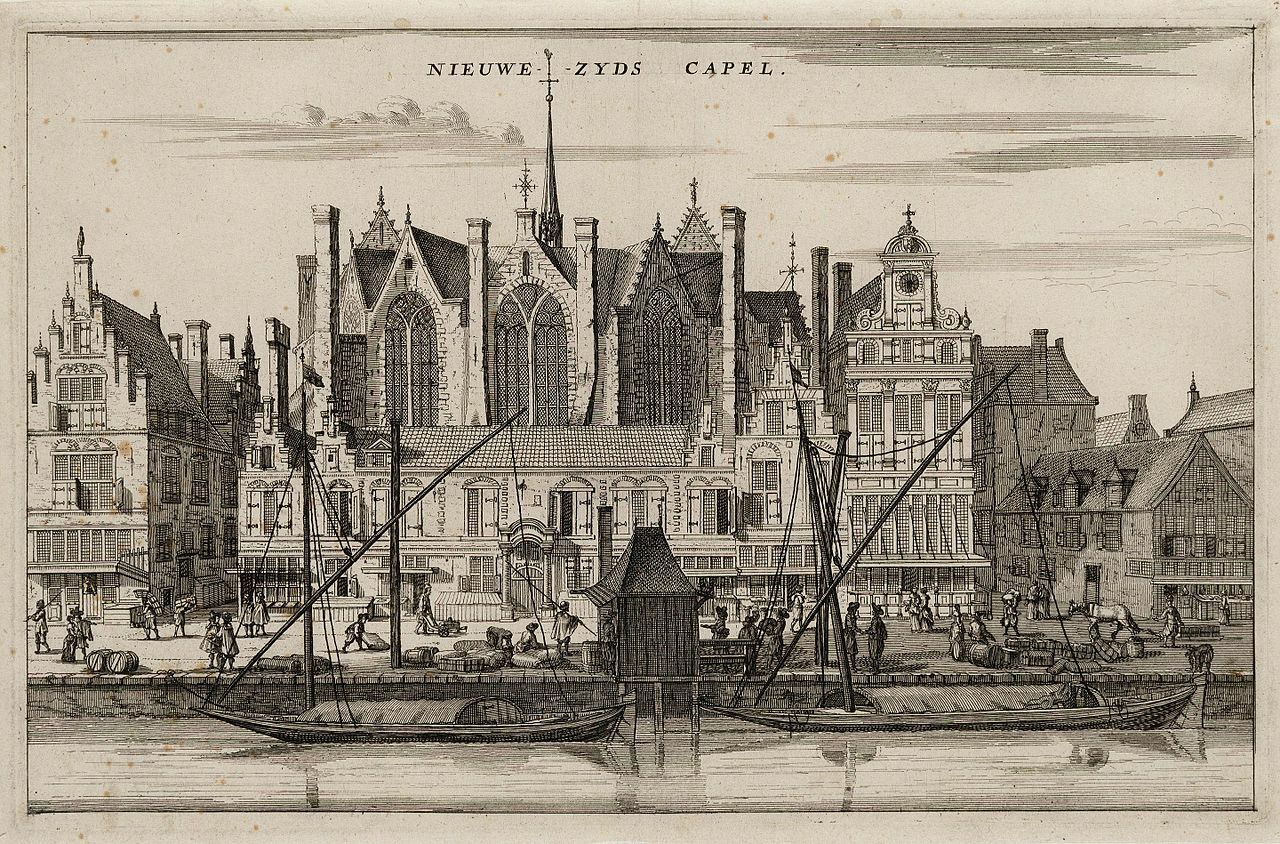

The sick man evidently did not survive, despite vomiting a miraculous bread up. Within two years his house had become the Heilige Stede, a hot spot for visitors and worshippers. A chapel was built and word spread around Europe. By 1415 the chapel was in a poor state, and the town council took over the responsibility for it, which moved the crystal monstrance and its constantly refreshed bread to the Oude Kerk (the Old Church). Donation boxes were set up for money to repair the Heilige Stede chapel.

Engraving depicting the Heilige Stede or Nieuwezijds chapel in 1663.

Engraving depicting the Heilige Stede or Nieuwezijds chapel in 1663.© Wikipedia

The miracle procession

The oldest surviving account of the miracle procession in Amsterdam comes from an apothecary named Walich Syvaertsz (1549-1606). In 1604 he wrote a book called “Romish Mysteries”, in which he described the miracle procession from his memories of seeing it as a child. We borrowed heavily from that description. To read the text yourself, brush up on your old Dutch and click here.

It is important to remember that Syvaertsz lived through the so-called “Alteration” in 1578, when Amsterdam changed from being a Catholic city to a Protestant one. So the recollections which he makes are no doubt heavily influenced by his conversion and no doubt personal disapproval of the tradition, which had since been halted. It was also written as an old man, recalling the days of youth.

Although his account was written more than a hundred years after the time period we were attempting to describe in this episode, it’s the closest we could get. We also know how Amsterdammers do street parties and simply don’t think the general vibe of it would have changed too dramatically.

Sacrament of Miracle, painted by Antoon Derkinderen in 1889 for the Begijnhof Catholic Chapel, Amsterdam

Sacrament of Miracle, painted by Antoon Derkinderen in 1889 for the Begijnhof Catholic Chapel, Amsterdam© Wikimedia Commons

Sources

- De Amsterdamse herberg (1450-1800) – Geestrijk centrum van het openbare leven by M. Hell, (UvA)

- Theo Bakker’s Domein on medieval Amsterdam

- De Boerenwetering

- Eerste 300 Jaren

- van ‘die Plaetse’ tot de Dam

- Meertens Institut site about Miracle of Amsterdam and pilgrimages there

- Historiek ‘Een historische scheldwoordenlijst’ by Enne Koops

- De Oude Kerk te Amsterdam: Bouwgeschiedenisen restauratie by Herman Janse

- The Miracle of Amsterdam: Biography of a Contested Devotion by Charles Caspers & Peter Jan Margry

- A timeline with photos of items found during archeological excavation of Amsterdam, in the construction of the Noord-Zuid metro line.

- Hajo Brugmans – Opkomst en Bloei van Amsterdam

- J. Hartog, A.M Vaz Dias – Amsterdam van Toen tot Nu

- Historisch Amstelland

- Geert Mak – A Brief Life of the City

- Russell Shorto – Amsterdam: A History of the World’s Most Liberal City