The court of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, became widely known as the most extravagant and luxurious in Europe during the almost fifty years of his reign between 1419 and 1467. Using pomp, ceremony and patronage of the arts, an image was created of Philip as a wise, just and fair ruler; the “Grand Duke of the West”.

During the celebrations of Philip the Good’s marriage to Isabella of Portugal in Bruges, in 1430, he created the Order of the Golden Fleece; a military group that celebrated the chivalric tradition and served to add prestige and honour to the immense power that Philip had acquired in his schemes of territorial expansion.

The creation of such an order was part of a greater image of courtly splendour, festivity and spiritual devotion that Philip established in order to validate his rule and create stronger bonds of identity with his subjects. Even when those subjects went into rebellion against him, which Bruges did in 1436, his subjugation of them would include using these elements to reinforce their relationship.

Marriage to Isabella of Portugal

By 1430 Philip was in his early 30s and had already been married twice. As a child he had partaken in that great family tradition of being married off by his parents to the offspring of a political rival for matters of diplomacy. At the tender age of eight, Philip was engaged to Michelle, a daughter of the Mad King of France, Charles VI and Isabeau of Bavaria. But she died as well as the next woman he would marry, Bonne of Artois.

So here was this rich, virile man, and we say virile because he already had several illegitimate children with a vast dominion of lands, but still no legitimate heir to them. He was, simply put, a very eligible bachelor and a lot was riding on his next marriage. We can assume that Philip not only wanted to make a smart political move, but also to choose a wife who could ably perform her role in governance.

Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy, painted by the workshop of Rogier van der Weyden, 1450, Getty Center, Los Angeles

Isabella of Portugal, Duchess of Burgundy, painted by the workshop of Rogier van der Weyden, 1450, Getty Center, Los Angeles© Wikipedia

Philip investigated various possibilities before deciding to set his sights on Isabella of Portugal, daughter of King Joāo of Portugal and sister of the appropriately named Henry the Navigator, whose future sponsorship of voyages of exploration would become so crucial in establishing the early Portuguese thalassocracy during the Age of Exploration.

Isabella was born in 1397 and for her first thirty years had very little luck in her official love life. Attempts had been made by her father to capitalise on her marital worth, such as with the English in 1415, but all had failed. She was an intelligent and capable woman who was also linked by family to the Lancastrian English, her great-grandfather being Edward III – the King of England who had had himself crowned as King of France in Ghent roughly ninety years earlier which had started so much of the turmoil we’ve found ourselves mired in.

Philip always had to consider relations with the English and the French in every decision he made, and while his first two marriages had kept him close to France, by this stage the English had a very solid foothold on the continent and still engaged in conflict with elements of the French royal family. Philip was officially allied to the English and in a powerful enough position to no longer have to pander towards his very weakened, yet still technical sovereign, the King of France. He saw the potential in making this alliance to maintain the balance system he rested upon. So he sent a delegation to Portugal to figure things out.

Philip was officially allied to the English and in a powerful enough position to no longer have to pander towards the King of France

Seven months passed between the arrival of Philip’s embassy and the legitimisation of the marriage. Philip had sent his chamberlain/court painter Jan van Eyck as part of the embassy to Portugal, to take part in the negotiations and also with the instruction that he send back two portraits of Isabella for him. A sneak preview, so to speak. The two were actually officially wed with proxies and then Isabella and the whole contingent due to go back to Flanders waited a further eight weeks before setting off, with violent weather along the route creating further delays.

On Christmas day, 1429, her ship came to dock in Sluis, outside of Bruges and Isabella of Portugal arrived in the Low Countries. We can only imagine how she must have felt, but we can assume it involved generous portions of being cold and nervous. This kicked off a frenetic few weeks in the area as representatives of the Four Members of Flanders came to greet her and preparations were made for the wedding and Isabella’s grand arrival in Bruges. Although the wedding itself was a low-key affair in Sluis on January 7, her entrance into Bruges the following day was a fantastic display of the wealth, extravagance and ostentatiousness for which the Burgundian court became renowned.

Isabella of Portugal and Philip the Good by an unidentified painter

Isabella of Portugal and Philip the Good by an unidentified painter© Wikipedia

Order of the Golden Fleece

During the wedding celebrations in Bruges, Philip created a chivalric order known as the Order of the Golden Fleece. Such groups had been around for a long time. They were basically lads clubs for rich knights. High-born nobles with certain ideas about their family’s glory could come together and make agreements about ways to behave and whether to go and fight wars or not. Being in an order increased the perceived valour and honour of a knight who was anointed in one. At this stage in our story we are coming towards the end of chivalric tradition and the role of knights in society, but the Order of the Golden Fleece simply dripped with class and was another mantle upon which Philip could demonstrate his extremely high prestige.

Meetings of the Order of the Golden Fleece were known as Chapters, and they would come together at irregular intervals; between 1431 and 1559, they met in total 23 times. These were moments of great pomp and circumstance and would be huge events for the places that held them. During the Chapters, there was a kind of behavioural review in which members had to swear that they had done nothing to damage or cause offence to the honour of the Order. If it was decided that they had, the sovereign could determine and mete out punishment. If it was decided that they hadn’t done anything disgraceful, they would be patted on the back for a job well done but then urged to do even better. After this, the sovereign himself would go through the same process with the knights of the order laying judgement on him too and admonishing him for misdoings, something which would occur quite often with the next Duke of Burgundy after Philip.

Philip, wearing the collar of firesteels of the Order of the Golden Fleece which he instituted, After Rogier van der Weyden, circa 1455, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon

Philip, wearing the collar of firesteels of the Order of the Golden Fleece which he instituted, After Rogier van der Weyden, circa 1455, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon© Wikipedia

As a supposedly militant body, members had to demonstrate proficiency in martial arts with some sort of weapon. But given that the whole thing was shrouded in symbolism designed to just boost self-image, and that it included some pretty old and non-militant men, it is doubtful that members had to do more than wave a sword around, or twirl a staff around a bit, if anything at all. There were strict guidelines on what they had to wear and when they had to wear it, whether red or black or white robes or whatever. One rule was that they had to wear, every day, a special golden collar which they received upon entrance into the order.

The heirs of any knight of the order who died were, honour band to return the collar to the Duke of Burgundy for him to give to the next member. Apparently one of those collars today is worth fifty thousand euros. As you might imagine wearing such a thing all the time is not exactly practical so this rule was quickly amended so that they could just wear the sheep pendant on a silk string, and in battle they were allowed to replace it with an engraving on their armour so that nobody would grab it and take off with it.

The ceremonies which they undertook were tied up with the strict Catholicism of the time, so included mass and prayer, but often recognition of deceased members, whose names would still be called out in the role call but be followed by the words Il est mort (He is dead), with a candle then being lit displaying the dead knight’s coat of arms.

Necklace from the Spanish branch of the Order of the Golden Fleece

Necklace from the Spanish branch of the Order of the Golden Fleece© Curtius, Liège

Throughout the almost six hundred years since its creation, the Order of the Golden Fleece has consistently been considered the most prestigious and exclusive Christian order. Membership meant that you could join no other chivalric club (except for royalty who were the leaders of those clubs). Throughout history, it would split into two branches, one Austrian and one Spanish, but only the Austrian can trace a direct line of obedience to the religious order that Philip the Good summoned into existence on his wedding day in 1430. So even though the membership capacity was thus doubled to fifty at any one time, it still means that only around 1300 people have ever been part of it. More recent members of the order include Akihito, former emperor of Japan, Queen Elizabeth II of the UK and Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands.

Philip’s patronage of the arts

By the 1530s Philip had settled into his role as the Grand Duke of the West. With the instability that had continued rocking the French throne and by keeping himself out of conflict with the English he established probably the most dependable regime in western Europe. He ruled a diverse array of subjects, who lived in culturally different provinces, each with their own traditions and historical quirks.

Philip needed to find ways to build connections between himself and them as best he could and this was usually done in his family’s manner of throwing festivals, banquets, and giving gifts to the right people. All of it was to reaffirm his curated image of Burgundian prestige and an understanding of what the relationship between him and his subjects was, which was built on three pillars: justice, equity and common good. Don’t get confused between equity and equality. Equity meant that essentially everyone should be on the same page that Flanders was legally his land, he the prince had the power of justice and that his subjects were owed and could expect his protection. One of the most evident ways that Philip fostered that identification and relationship was through his patronage of arts.

Burgundian court

Burgundian court© Wikipedia

Musicians, poets, painters and sculptors were drawn towards the Burgundian court, paid handsomely, and encouraged to create works that celebrated the kind of cultural elements that would become associated with what we understand to be the Renaissance. The social elite in all his domains would seek to imitate his lead and so put ever more value on patronage and a culture began developing in which artists could strive to improve their skills and reach their potential.

A group of composers who became known as the ‘Burgundian School’ emerged in Bruges, Brussels, Lille and Arras. The encouraging atmosphere of the Burgundian court allowed for the creation of authorised secular music and this cultural freedom would engender an atmosphere that kept inspiring and drawing in more musicians. There was a shift from Paris to Burgundy as the centre for the modern fashion of polyphonic vocalised secular music. The best-known composers of the time include Gilles Binchois and Guillaume Dufay.

Philip was also a patron of the arts in other ways, with his court assembling some of the greatest painters of the time. We briefly mentioned Jan van Eyck earlier, Philip’s chamberlain and court painter who had been sent to paint those portraits of Isabella before the wedding. Considered to be one of the greatest early painters of the Low Countries, van Eyck had previously been in the employ of John of Bavaria in Holland, but after his death, van Eyck had travelled south and ended up in Philip’s household. Van Eyck was a great exponent of using oil-based paintings in his work, as well as a drying agent which was becoming popular for artists in the Low Countries at the time. His expertise in applying specific layers of colour, of varying transparency or opaqueness and being able to apply extra layers meant he could portray depth, light and texture in a way that must have been absolutely mindblowing at the time.

Some masterpieces of Jan Van Eyck who was the chamberlain and court painter of Philip the Good

Some masterpieces of Jan Van Eyck who was the chamberlain and court painter of Philip the Good© Wikipedia

Philip found ways to implement his power in different ways in different places, whether in towns or regional areas. If you cast your mind back to the beginning of the 14th century, you’ll remember that Flanders was constantly facing the prospect of being absorbed into the French realm. Even Philip’s grandfather and father had concerned themselves more with French affairs than those of their Low Country domains, and we have seen how Philip had set out on a very different approach, creating a sense of centralised low country autonomy. Philip built up a clientele network amongst the local elite and nobility with him at its centre, using the arts and other means by which to sell the idea of a strong and independent Flemish identity, but with a powerful prince.

In Holland and Zeeland, which was mired in the civil war between Hooks and Cods, whose respective levels of influence varied from town to town, Philip set about putting in his own ducal administrators and trying to build the same sort of clientele network. However he had to tread extremely carefully because of the parochialism that lingered between Hooks and Cods.

Because he was not physically present much in these northern domains he could not maintain the relationship with his subjects as easily as in Flanders or Brabant, where traditions such as the Joyeux Entrees and glamorous Burgundian weddings performed those roles, and also where there were literally central courts. In Holland and Zeeland local power bases were bound to grow, and Philip appointed a stadtholder to rule in his stead, and act as a conduit by which he could make decisions for the territories. The noblemen he appointed to this position were consistently foreigners to Holland, and also members of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

Revolt in Bruges

The Burgundian Dukes, when they became the Count of Flanders, proved themselves pretty apt at balancing the simmering angst that we have seen consistently arising between Flemish urban and regional needs and the demands of their counts. To be fair, Philip the Bold had learned well from his father-in-law, Louis of Male, and John the Fearless had shown himself willing to put a lot of responsibility onto Philip the Good from a young age.

We saw around the time of the Liège rebellion, in 1411, how a young Philip had navigated his way through rebellion by the Bruges militia. They had abandoned his father’s army in France and refused to reenter Bruges until Philip did away with the calfsvel law, which had forbidden them from assembling without the count’s permission. Philip had given this and other concessions, and so avoided full-scale rioting in Bruges and the always present threat that revolt could ignite in towns and cities across Flanders.

Philip sold Joan of Arc to his English allies in 1431, who then burned her alive

The revolt that kicked off in Bruges in 1436 was brewed from the same ingredients that the Flemish town revolts we’ve seen already were; different factions defending their rights or pushing for greater political influence and rights against their count on the backdrop of certain economic and social conditions. Of course, by ‘certain economic conditions’ we mean ‘the ability to get cheap wool from England.’ Also, he also captured Joan of Arc, who had built a stunning career to become a top French general at fifteen years old. Philip sold her to his English allies in 1431, who then burned her alive.

In 1435 Philip ditched his alliance with England and signed the Treaty of Arras, renewing his allegiance to France. This was effectively an end to the divisions between Burgundy and France that had seen civil war and the assassinations of the Duke of Orleans and John the Fearless. For the Flemish people it was the sort of stuff that nightmares are made of. Their long-sought trade agreement with England was threatened now that the hundred years war had kicked off again, and so much of their economic stability depended on it.

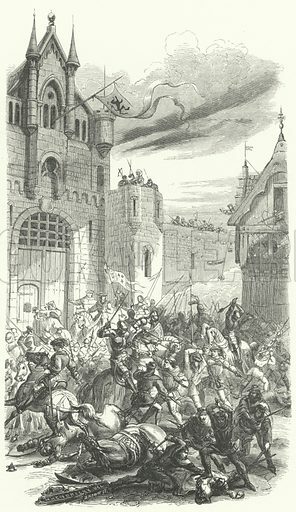

Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, fighting against an uprising in Bruges, 1437. Illustration for Histoire De Belgique by Theodore Juste, circa 1870)

Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, fighting against an uprising in Bruges, 1437. Illustration for Histoire De Belgique by Theodore Juste, circa 1870)© Wikipedia

At the same time, other economic power bases were beginning to come into conflict within the entangled web of international business. The Hanseatic League and Holland started jabbing at each other, and then took the next step to piracy which caused instability for international commerce. Essentially, the people of Flanders were in a recession and looking at how big events beyond their control were probably going to cause even greater uncertainty to their already uncertain lives. Then, in the midst of all this, Philip told the towns of Flanders to get ready and set about assembling an army to help him to attack the English at Calais in the middle of 1436. The Flemish were not happy about this. Eventually it led to yet another revolt, against Philip the Good, in 1437. It was a messy incident but eventually Philip took control of the city, levied a huge fine, of 200,000 golden riders, and stripped Bruges of many of its privileges.

Joyous Entry

Negotiations continued, however, between Burgundian, French and English entourages to try and sort out all the messiness of what had just gone down and to try to bring matters to a close. In 1439 emissaries from all three sides met just outside the town of Gravelines, right near the border of English and Burgundian territories. Representing Burgundy was Isabella of Portugal, the Duchess, who was a sympathetic choice for the English due to her Lancastrian family ties, whilst the English were represented by Isabella’s uncle, Cardinal Henry Beaufort.

A gigantic temporary town was erected, a bunch of huge pavillions and tents, with apparently ostentatious displays of hospitality between the two sides. The negotiations dragged on for months and although no lasting peace was decided here between England and France, Isabella was able to marry her and Philip’s eldest son and future Duke of Burgundy, Charles, at the tender age of seven, to the daughter of the French king Charles VII.

Probably the most important thing to come out of this conference for our story is that trade relations between England and Flanders were once again normalised after Isabella and her uncle apparently sat down face to face together and hashed out a bunch of arrangements. A treaty was made to ensure the safety and security of merchants from both sides in their dealing in the other’s territories, and this agreement would continue on until the end of the century.

Isabella was able to marry her eldest son and future Duke of Burgundy, Charles, at the tender age of seven, to the daughter of the French king Charles VII

Perhaps even more spectacularly, however, in these negotiations Isabella was also able to secure from the English the release of Charles, Duke of Orleans, from their custody. Charles was the son of Louis of Orleans, who Philip’s father John had had butchered on the street in Paris. He had been part of the Armagnac faction with whom the Burgundians had had so much tension and after the battle of Agincourt he had been captured by the English and then held hostage for twenty-five years in the Tower of London. Isabella had been able to convince most of the French nobility to throw in cash to buy his release, and Charles himself had agreed that he would give up on the quest for revenge for his father’s death which he had sworn himself to all those years ago.

By November, Charles, Duke of Orleans, was a free man and met by Isabella, apparently speaking better English than French, which makes sense considering he’d spent over half of his life in an English prison. In these negotiations, Isabella had proven herself to be extremely capable and Philip had made a very wise choice indeed picking her to be his wife. So with this new trade agreement sorted out, and having an extremely high profile former enemy now in their debt and in their possession, the Duke and Duchess of Burgundy decided that the best thing to do now was to show Flanders who was boss, and did so by embarking on a tour through the county, showing off with as much Burgundian splendour as possible.

After the revolt in Bruges, Philip would have seen his relationship with his subjects, not only in Bruges but quite possibly in wider Flanders too, as somewhat fractured. The carefully crafted image of Burgundian strength, prosperity and culture would need to be used to reacquaint the Flemish people with the pillars of justice, equity and common good that their relationship was based on. So Philip and Isabella, with the freshly released Duke of Orleans in tow, made a series of Joyous Entries into various towns around Flanders, beginning with Saint-Omer. They were those highly choreographed, ceremonial affairs in which a duke would make a grand entrance into a city during which their rule would be recognised, and in turn the ruler would himself acknowledge the rights and privileges of the town. It was kind of like a big show between ruler and ruled where both tried to show the other how great they were, and that even though they didn’t probably didn’t actually like each other very much, they would all pretend they did.

Jean Wauquelin hands over his 'Histoire d'Alexandre' to Philip the Good. The book, for which the author was paid in 1448, is one of the first known examples of the duke's patronage.

Jean Wauquelin hands over his 'Histoire d'Alexandre' to Philip the Good. The book, for which the author was paid in 1448, is one of the first known examples of the duke's patronage.© Wikipedia

Philip the Good built upon the strong Burgundian identity he had inherited and as his domain expanded he cultivated an identity as the Grand Duke of the West. Through his patronage of the arts he made it fashionable for social elites in the Low Countries to invest in musicians, sculptors, painters, writers, entertainers and anybody else who could bring prestige to a court in a cultural manner. By doing this, he engendered a connection between his subjects and himself.

The uprising in Bruges in 1436 would not be the last time he would have to deal with Flemish urban revolt; it happened because of a political weak-point that was far more ancient than the House of Burgundy – the wool trade with England. Philip experienced how he could still lose control over the loyalty of some of his subjects and would be forced to extreme measures, such as blockading Bruges. His Joyous Entry into the rebellious city in 1440, and the splendour with which it was celebrated, in which he was compared to Christ himself, would become a template he would use to reinforce his authority and respect for the Burgundian regime upon any city that might try to rebel against him again. Philip still has another few decades of rule ahead of him and in that time the Burgundian Netherlands would reach its peak.

Burgundian territories under Philip the Good, reigned 1419-1467

Burgundian territories under Philip the Good, reigned 1419-1467Sources

- Jason and the Argonauts through the Ages by Jason Colavito

- Charles the Bold, the Last Duke of Burgundy by Ruth Putnam

- ”Fleece as Blonde Hair”

- “Order of the Golden Fleece” by J. Balfour Paul in The Scottish Historical Review Vol. 5, No. 20 (Jul., 1908), pp. 405-410

- The Chronicles of Enguerrand de Monstrelet

- Beggars, Iconoclasts, and Civic Patriots: The Political Culture of the Dutch Revolt by Peter Arnade

- Henry VI by Bertram Wolffe

- “The ‘Terrible Wednesday’ of Pentecost: Confronting Urban and Princely Discourses in the Bruges Rebellion of 1436–1438” by Jan Dumolyn in History Vol. 92, No. 1 (305) (january 2007), pp. 3-20

- “The Archives of the Order of the Golden Fleece and Music” by Barbara Haggh in Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 120, No. 1 (1995), pp. 1-43

- “Ducal Patronage and Performance as a Power Expression in Conquered Cities: The Case of the Burgundian Low Countries” by Oskar Jacek Rojewski

- “The nervecentre of political networks? The Burgundian Court and the integration of Holland and Zeeland into the Burgundian state” in The Court as a Stage: England and the Low Countries in the Later Middle Ages by M. Damen

- Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy, Volume 3 by Richard Vaughan

- The Promised Lands by Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

- Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States: The Unification of the Burgundian Netherlands, 1380-1480 by Robert Stein