From Jeanne Brabants to Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui: Royal Ballet of Flanders Celebrates 50 Years

On 2 December 1969 dance legend Jeanne Brabants’ dream was fulfilled in the foundation of the Royal Ballet of Flanders. Fifty years, a new name – Opera Ballet Flanders – and an opera fusion later, the only remaining professional ballet company in Belgium faces new challenges. A bird’s eye view of a turbulent history.

On 20 October Opera Ballet Vlaanderen (Opera Ballet Flanders) presented the premiere of Cantus Firmus/Mea Culpa: Brabants/Cherkaoui, a piece of dual choreography, celebrating and bridging fifty years of the Royal Ballet of Flanders: from the first empowering steps by founder Jeanne Brabants (1920-2014) to the intercultural social criticism of the current artistic director Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui at Opera Ballet Flanders.

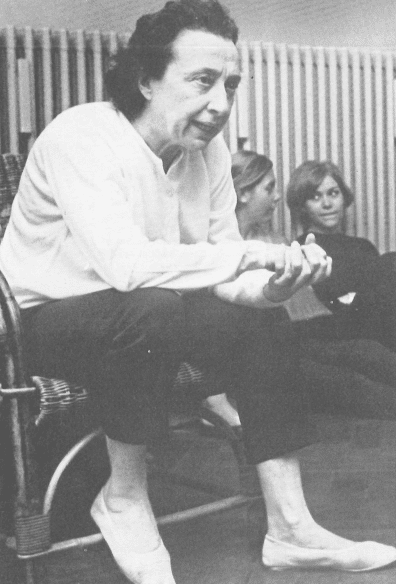

Jeanne Brabants (1920-2014)

Jeanne Brabants (1920-2014)In Cantus Firmus the Royal Ballet of Flanders returns to a work by Brabants, who created the piece in 1968 for her students at the Royal Ballet School Antwerp. In 1970 she revised the piece for the new Royal Ballet of Flanders. We see abstract pointe dance of a moving purity, focusing not on technical prowess but on clean lines of movement and references to modern dance. The choreographic space is delineated, with lots of frontality and movements towards the audience. It is remarkable how the work retains that fresh feel today. The original set, designed by Brabants’ regular scenographer John Bogaert, is an ingenious, manoeuvrable construction of ropes between two arches, inspired by J.S. Bach’s organ and Calder’s kinetic sculptures. It fitted into a single suitcase, like the gramophone version of the Bach psalms: Brabants wanted to be able to perform everywhere, from China and the United States to Flemish parish halls. In the current format, B’Rock Orchestra plays live on early musical instruments.

Mea Culpa, the second part of the festival programme, is a performance originally created by Cherkaoui for the Ballets de Monte-Carlo in 2006. Long before the theme burst out into the performing arts, Cherkaoui was staging the impact of colonialism on a shifting layer of power relationships between master and slave. Cherkaoui places two Congolese musicians on stage for this performance. He mixes confrontational video work, African dance and song with the Renaissance music of Heinrich Schütz. He transposes the virtuosity of the dancers into the sometimes biting language of movement, conveying the force of his theme. The subject of gender fluidity is also raised: somewhere along the way someone runs away from a drunk, drifting man and the androgynous Drew Jacoby takes over the male lead role. The fact that this is a regular ballet company with a fixed hierarchy contributes to the mix: there are (ex)-dancers from Cherkaoui’s contemporary dance company Eastman and guest roles for dancers from other companies and dance traditions. Mea Culpa is theatre dance of the purest kind. At the same time, it has the social relevance that Brabants so admired in The Green Table – the anti-war dance theatre of Kurt Jooss and Sigurd Leeder which she saw on stage in 1936.

But Mea Culpa’s set for won’t fit into a suitcase, and Brabants would hardly have dared to dream of costumes by Karl Lagerfeld.

Alongside the fresh purity of Cantus Firmus, Mea Culpa reveals a self-confident, well-oiled machine with enough production leeway to make this choreography a crowd-pleaser and prize-winner. Whatever Cantus Firmus has been in the past. Can we then conclude that Cherkaoui’s appointment as artistic director, his star quality, and his mix of daring and allure, which Brabants also strove for, enriches the Royal Ballet of Flanders?

Dance as autonomous art discipline

Let us dive into history. In 1969 – a year of vision and future opportunities – the Royal Ballet of Flanders started up under Brabants’ initiative. This was the pedal point of visionary ambition after decades of steps towards putting dance on the map as an autonomous art discipline. The genesis of the Royal Ballet of Flanders is closely connected with its personal history and reads like a battle for empowerment on many fronts. The company comes with a political agenda too. The first Flemish minister of culture gave them the green light in December 1969, a strong signal at the height of the Flemish language struggle.

According to Brabants dance needed to establish lasting autonomy

Brabants herself fiercely defended Flanders’ dance talent at a time when all things French-speaking had higher status. But for Brabants, Flemish empowerment was just one aspect. For her, it was first and foremost about securing a sustainable foundation for dance, about institutionalisation, visibility and a dependable pedagogical basis as levers to that end. In 1987 a change in directorship resulted in dance star Maurice Béjart leaving opera house De Munt, and the resources that were subsequently freed up went elsewhere; to Brabants this again was strong evidence that dance needed to establish lasting autonomy.

Flanders’ own ballet school

Brabants’ mission had a great deal to do with the structural gaps she had encountered while learning to dance as a child. Only in 1936, after two years of dance gymnastics, was she able to start a private, semi-professional course in modern expressionist dance with a rudimentary ballet foundation, under Lea Daan in Antwerp. She was sixteen by then. In her family, it was the only option at a time when classical ballet was still associated with abuses at the 19th-century Paris Opera (involving poverty and prostitution). Just before World War II, she began a course with the masters of German dance expressionism themselves, in England, where Kurt Jooss and Sigurd Leeder had found asylum, along with movement theoretician Rudolf von Laban. When the war broke out, Brabants was forced to return home.

Lea Daan (1906-1995)

Lea Daan (1906-1995)© Jean Van der Haegen

After the war, everything German was out of favour. Determined and pragmatic as she was, Brabants went in search of instruction in ballet technique in London and Paris. She found a teachers’ course under Ninette de Valois at the Royal Ballet School. That allowed her to emerge in Europe as one of the transitional figures between theatre dance and an innovative ballet form with modern influences. Birgit Cullberg in Sweden played a similar role. After starting her school and company with her sisters Jos and Annie, in 1951 Brabants succeeded in starting a ballet school at the opera in Antwerp. Ten years of tireless lobbying and the support of her clan led to the Royal Ballet School, a state-run school proving a general education and an officially recognised diploma.

New Flemish dance wave

With Brabants’ retirement approaching in 1985, a battle over dance ideology arose on various fronts. She was so vehemently opposed to the appointment of the Russian Valery Panov as new director that she left a year early, in 1984. Panov was a brilliant dancer from Kirov, but to her, he represented an outdated Soviet-style, not suited to a young, forward-looking company. At the time, the new Flemish dance wave was just around the corner. For the new generation, ‘old-fashioned’ ballet formed a perfect target. It was the beginning of an idiosyncratic Flemish feud – again politically coloured, since it was about subsidies, about pennies.

After Valery Panov had moved on, Antwerp citizen Robert Denvers brought peace – at least to the ballet ranks. Under his directorship, the company moved to a new building on Antwerp’s Eilandje, and he parried criticism from the contemporary dance field by inviting Jan Fabre for an updated version of Swan Lake.

In 2005 a new fury made her entrance in the form of the Australian Kathryn Bennetts. With years of experience as a teacher with William Forsythe’s company, she brought the corps de ballet to a clear pinnacle, and to the big international stages, as Forsythe allowed her to rehearse a number of his works with the Royal Ballet of Flanders. Impressing the Czar

toured worldwide, attracting prizes in its wake. In Belgium the work was shown in venues exclusively focused on contemporary dance, engendering new mutual respect.

Awkward fusion with opera

Bennetts’ ambitions for the company, unfortunately, outstripped the subsidy pot. Concerned for the Royal Ballet’s financial situation, the Flemish government decided on a fusion with the Flemish Opera. Kathryn Bennetts appealed against the plan. Brabants, now past 90, published furious letters in the national media. To no avail: the fusion went ahead. In 2012 Bennetts resigned and the Portuguese Assis Carreiro took over. She came up with ways of performing ballet on smaller stages, but as a non-dancer, she didn’t resonate sufficiently with the company. She did bring in work by Cherkaoui for the first time.

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui© Dries Segers

Cherkaoui, too, had no background in ballet – he was trained in contemporary dance. He studied choreography with Alain Platel’s theatre dance company, later gaining experience for big ballet companies. He also worked with mentally disabled performers from Theater Stap in Turnhout. He too had won important prizes. Cherkaoui brought the Royal Ballet of Flanders a great openness to other dance styles and cultures. He invited innovative external ballet choreographers, which is precisely what Brabants had also worked so hard for. Cherkaoui also emerged as a figure to reconcile contemporary dance and ballet in Flanders: this season Alain Platel is on the programme with Choeurs, with the choir, orchestra and dancers of Opera Ballet Flanders. Next year they will host Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker with her version of Cosi Fan Tuti, bringing her own dance company Rosas.

A third pillar

The question remains which way the Royal Ballet of Flanders will go today. Which way it needs to go, which ways are open to it. Cherkaoui can do a great deal for the company’s international image and branding. But his dual role means that he is often absent. He is also the artistic director of his own company Eastman and makes regular excursions into pop culture – see his work for Beyoncé and Broadway. Will he succeed in guaranteeing the focus and enthusiasm to keep the entire company in public view in the long term, in Belgium and abroad? Can the house offer all 43 dancers enough tours and stage appearances?

Opera Ballet Flanders also wants to be a platform for ‘experiment, innovation, talent development, art education, inclusivity and intersectionality

Moreover, how much should we worry about the fusion with the Opera – which Brabants so wanted to avoid? From this season Jan Vandenhouwe is the new general director. He cherishes ambitious plans. Around the idea of openness and hybridity, in the new season, he wants to take Opera Ballet Flanders to the next level as an innovative art house. The focus of his plans is a complete third pillar alongside opera and ballet: a platform for ‘experiment, innovation, talent development, art education, inclusivity and intersectionality’, according to the press release. With eyes wide open to the diversity of Antwerp and Ghent, where the company has its venues, the house wants an opportunity for external perspectives and forms to fully interact with the medium of opera and ballet.

These are strong ideas. The question is what they mean for ‘ballet’ as an institution in the longer term. Brabants was ahead of her time in working boldly on a recycling model to ensure a historical continuum for dance and to prevent the loss of resources. The best students of her internationally renowned school gained places in the company. She shaped young choreographers, with an eye for innovation. Brabants also founded a teaching department, again with employment in mind, for instance in part-time music schools – where she also put dance on the map. She was intensely occupied with the social status and protection of dancers and provided a retraining budget after their short careers.

Uncertain future

Artistically, Brabants and Cherkaoui have no trouble seeing eye to eye across the 50 years that separate them, with their inclusive and socially committed view of ballet and theatre dance. Does the same go for Brabants’ cyclical model of anchoring and empowering dancers? The Royal Ballet is the Flanders’ last company with dancers in fulltime employment. (In contemporary dance and performance, such employment ceased many years ago – for instance, the Brussels Munt ended Rosas’ position as a regular ensemble in 2006.) Does the Royal Ballet till have space for and an interest in the dancers of the Royal Ballet School? And what about Junior Ballet Antwerp, recently established for young dancers to gain stage experience – currently on payment of an entry fee?

Dancers of Opera Ballet Flanders in 2016

Dancers of Opera Ballet Flanders in 2016© Filip Van Roe

Or are we heading for a dance world in which no institute or company offers dancers job security? Where ‘the ballet’ in time will have to make way for an economic model of self-management, with individual dancers in extremely precarious situations? Recently the new Flemish minister of culture announced a draconian cut in project subsidies for this category of artists. We hope that the planned third pillar of Opera Ballet Flanders will bring comfort to those talented, young dancers, as they provide the impulse that keeps the dance field alive. It would also be wonderful if Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui were to honour Jeanne Brabants’ ideas of social involvement and empowerment in this great Flemish artistic institution.