The Battle of the Bulge Sealed Nazi Germany’s Fate

On 16 December 1944, the Germans launched their last major western offensive campaign of World War II. Operation Mist, better known as the Ardennes Offensive and the Battle of the Bulge, took place in the densely forested Ardennes region of Belgium and was intended to split the Allied forces and re-take the strategically important port of Antwerp. It was the largest and bloodiest battle that American soldiers have ever fought. The battle lasted five weeks and was won by the Allied troops.

‘It’s just as comfortable here and we feel just as safe as we did when we were in England,’ the English soldier Joe Schectman wrote to his parents on 15 December 1944 from the area around Bastogne. He didn’t have long to enjoy this peace and quiet, though, because at half past five on the morning of 16 December the last German offensive on the Western Front began.

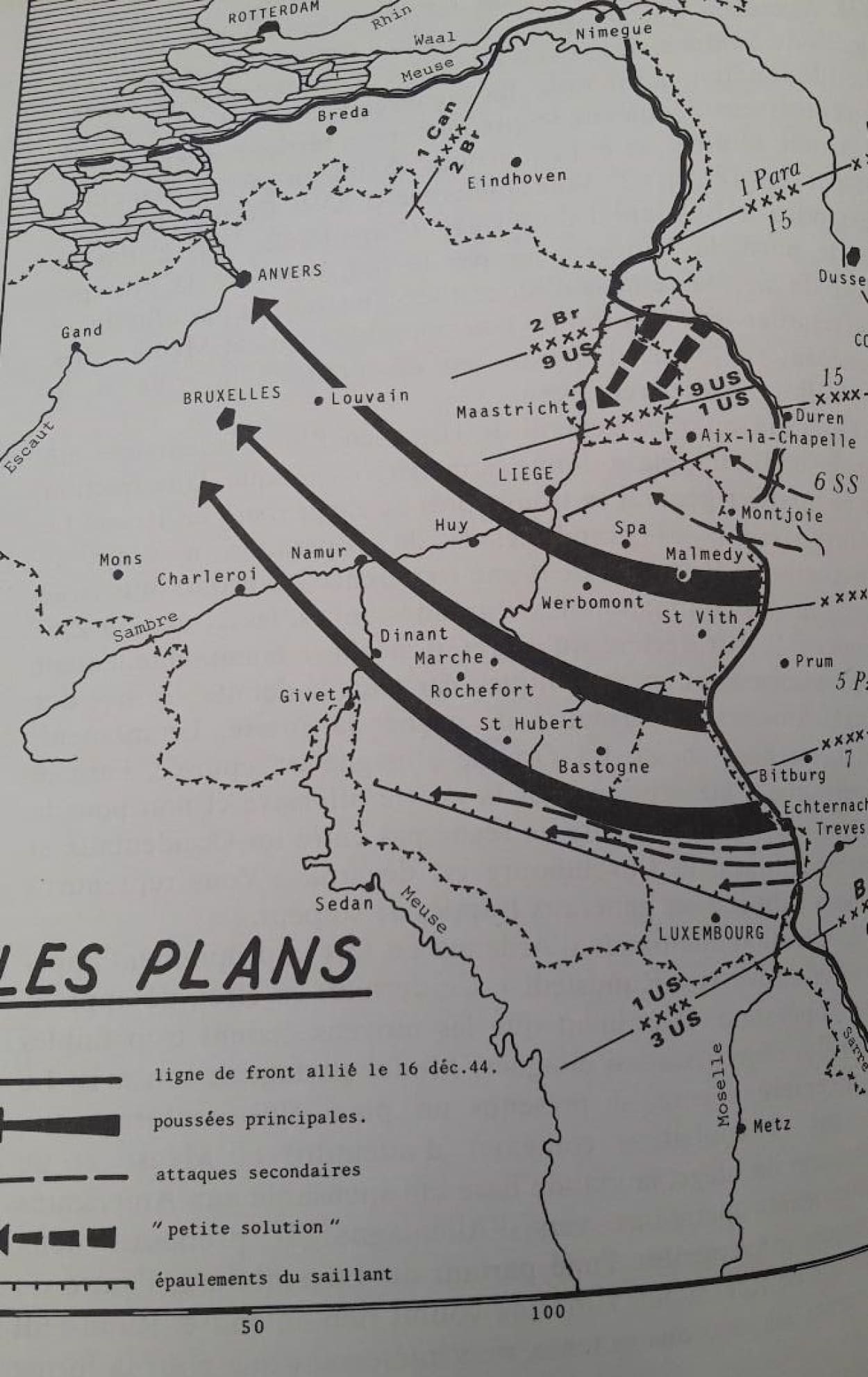

The plan, devised by Hitler himself, was to launch a large-scale attack across the Maas with the aim of re-taking Antwerp and driving a wedge between the advancing Allied troops. According to the Dutch historian Lou de Jong, Hitler’s objective was chiefly political. The Führer was presumably hoping that this attack would lessen the Allies’ will to continue the war and that British and American differences of opinion about military and political strategies would increase.

German machine gunner marching through the Ardennes in the Battle of the Bulge

German machine gunner marching through the Ardennes in the Battle of the Bulge© Wikimedia Commons

This German plan has been given different names: the Ardennes offensive, the Battle of the Bulge, and sometimes it is mistakenly called the Von Rundstedt offensive. Field Marshal G. Von Rundstedt was the commander of the Western Front. He realised that Hitler’s plan was insane, but he didn’t dare contradict the Führer. The Germans called the plan ‘Wacht am Rhein’ (the Watch on the Rhine), with the intention of creating the impression that it was more of a defensive plan designed to stop the advancing Allies at the Rhine. A strict timetable was drawn up for the attack: 16 December: D-day; 18 December: the Maas is reached; 19 December: the Maas is crossed; 23 December: Antwerp is captured.

To implement this plan a military force of around 220,000 soldiers was assembled. They had enough fuel to reach the Maas; after that the German troops would make use of captured Allied depots. Liège and Antwerp were bombarded with V1 and V2 bombs. The assault was to be supported by two special units: a group of parachutists and a group of German servicemen dropped behind Allied lines and operating in American uniforms. This unit was under the command of Colonel Otto Skorzeny, the ‘most dangerous man in Europe’. Many of his men were unmasked because their American English wasn’t good enough or because they turned out to be wearing German underwear beneath their American uniforms.

American soldiers make their way through a snowstorm and prepare to shoot at a Nazi plane, January 1945

American soldiers make their way through a snowstorm and prepare to shoot at a Nazi plane, January 1945© Wikimedia Commons © National Archives

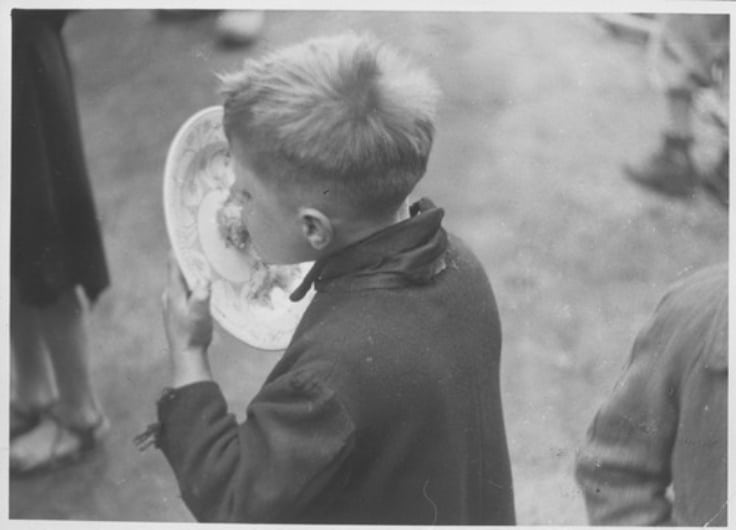

Over a front of 125 kilometres, from Monschau to Echternach, the German military force faced a total of 85,000 American soldiers. Initially the German action had some success and the American troops came under very great pressure. However, their indomitability was best characterised by the Battle of Bastogne. On 21 December the Germans surrounded the town. But when German officers came to demand surrender, the American commanding officer General Anthony McAuliffe answered ‘Nuts’. Or at least that’s how the story goes, because in fact the general hesitated over his answer for a long time and the German officer who had to communicate the answer didn’t quite understand what the general meant by it. Four days later General Patton relieved the town.

Two American soldiers on the streets of Bastogne, a city under siege by the Nazi army, 19 December 1944

Two American soldiers on the streets of Bastogne, a city under siege by the Nazi army, 19 December 1944© National Archives

On 24 December the German offensive became stuck at the Maas. Weather conditions also improved, which meant that the Allies were able to use their air power. By 25 January 1945 the battle was over. It had lasted five weeks, cost fifty thousand lives and had changed the front line hardly at all.

The devastated ruins of the Belgian city Stavelot, 30 December 1944

The devastated ruins of the Belgian city Stavelot, 30 December 1944© Wikimedia Commons

Seventy-five years on, the Battle of the Bulge still fires the imagination. Heroic combat encounters, in exceptionally bad climatic conditions, have given rise to many stories and myths, which are reflected in eleven museums in Belgium and Luxembourg.

The Mardasson Memorial in Bastogne

The Mardasson Memorial in Bastogne