Within the confines of society’s norms and expectations, Roland Gunst – half Flemish, half Congolese – uses installations, performances, film and video to explore the search for his own identity. He has travelled from rage to reconciliation. Flandria is his first musical theatre performance.

Roland Gunst

Roland Gunst© Freddy Willems

It would be odd – offensive even – to call Roland Gunst (1977) a new voice on the arts scene. Gunst has been a filmmaker, musician and artist for over a decade, so he can hardly be called a debutant. Perhaps we mean new in the sense that it’s only now that we’re starting to really notice him and his work, a phenomenon not unusual for Black, Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) artists, who now suddenly find themselves in the spotlight of a white-dominated arts and culture sector. Roland Gunst is only really a newcomer when it comes to theatre, and with Flandria (2019) he tries his hand at musical theatre, together with composer Benjamien Lycke, soprano Emma Posman and the Kugoni Trio.

Gunst’s work has strong autobiographical roots. Again and again it tells the story of the search for his own identity, within the restrictions that society imposes on it. At the end of the 1980s – when the beginnings of the extreme right party Flemish Block (now known as Flemish Interest) could be felt– Gunst, son of a Flemish father and a Congolese mother, ended up with his family in Nieuwpoort, a village on the Flemish coast.

Survival Strategy

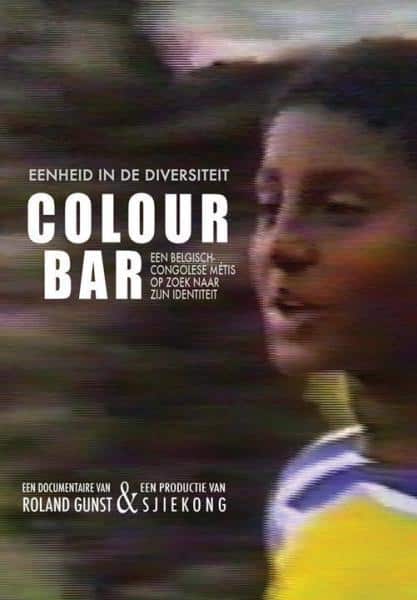

As a child of colour in completely white surroundings, Gunst initially did his utmost to be as Flemish as possible in order to ensure his place in society. It was a “survival strategy,” says Gunst. He became aware of how all encompassing this drive was during the production of the documentary Colour Bar (2011). “I used the outside world as a reference point for a long time. It is how socialisation works: you look for a group and you try to mimic them as closely as possible,” says Gunst.

Colour Bar (2011)

Colour Bar (2011)At school, the young Gunst internalised people’s preconceptions about his African heritage, making him fear that he lacked ‘civilisation’. “I felt a strong urge to prove my intelligence and good manners. So I made sure I belonged to the very top of the class, and that I was among the best pupils at school. But at the same time I was a troubled student and my behaviour didn’t make things easy for my teachers,” he says.

Creating Colour Bar, in which Gunst reconstructs the search for his identity, brought about a change of tack. Thanks to conversations with people who had been in a similar position, he realised that his mission to become truly Flemish (or even better: hyper-Flemish) was unachievable for him, simply because the Flemish themselves do not know what it means to be Flemish. Gunst explains, “At the time I was really working on this, I asked Flemish people if they could give me a clear definition, so that I wouldn’t get it wrong. That turned out to be a difficult task. It’s much easier to say what you are not, rather than to explain what you are. But if that’s difficult for a Flemish person, how can you ask an outsider to try and fit that mould?”

Only then did Gunst realise just how big the impact of forced assimilation is – of the experience of being black within a white-dominant perception of civilisation. It is a burden that has saddled him with a sense of inferiority, which will be with him for a long time yet. Gunst translates the feeling he had as child, desperate to fit in, into an artistic strategy.

An exercise in becoming Flemish

What jumps out at you the most is the LION-project, a multi-year project which also encompasses the musical theatre performance Flandria. In its first phase (2011-2013), LION is an exercise in becoming Flemish. Through video installations and lecture performances we see how John K Cobra, Gunst’s alter ego, applies a ‘therapeutic model’ to himself. This is supposed to guarantee his integration into Flemish society. He appears, for example, wearing a white latex mask to ensure there are “only white faces on the streets”. At the same time his ‘being black’ remains inextricably part of his identity.

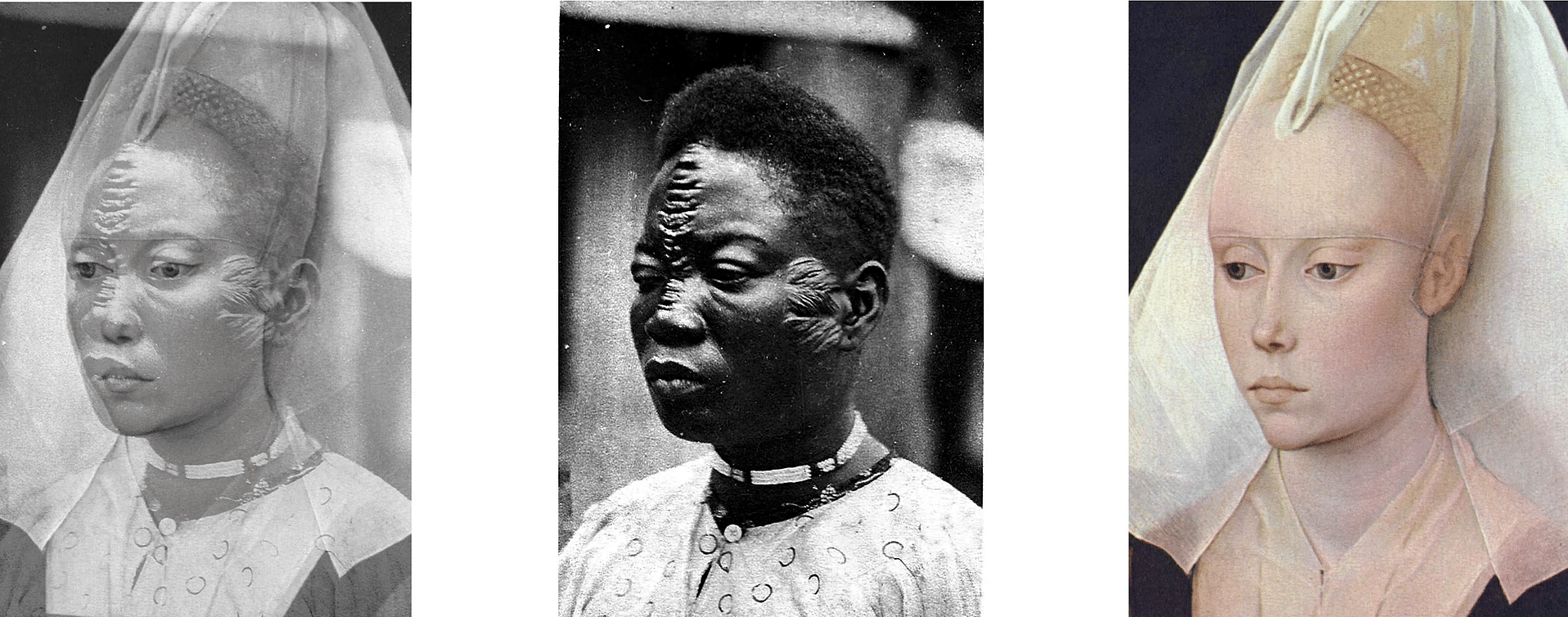

In the second phase of LION (2014-present) Gunst lifts his personal quest to a societal level: from now on, “King LION” doesn’t just want to solve the integration problem for himself alone; he wants to solve it for all of Flanders. ‘Integration’ or ‘assimilation’ have become hostile terms: focusing on Europe’s mixed heritage, this black Lion of Flanders now strives to replace the illusive dream of ‘purity’, with a new narrative that embraces transnationalism.

Gunst playfully turns the mythology, heraldry and symbolism in Hendrik Consciences’ novel The Lion of Flanders on its head. In his performance Flandria, a black king is treated like a saviour: by marrying his bride Flandria, he catalyses the transformation of a one-sided white way of thinking, into the ideology of ‘Afro-Europeanism’ – the awareness of Europe and Africa’s shared heritage.

Afro-Europeanism is an exercise in historical awareness, whereby the history of mankind is retold in terms of equal African-European influence. To do this, Gunst uses strategies such as reversal, fictionalisation and irony, but the conciliatory gesture that supports Afro-Europeanism is sincere. The storytelling in Flandria may be symbolic, but the facts are historic. “It’s a fact that since the 1500s more and more Europeans moved across to Africa, and vice versa. There was an exchange of knowledge and experience, and of course there was a simple exchange of genes too. Great noblemen from the Medici family and the Pushkins had African roots. When you’re aware of the exchange of biology, politics, culture, science… you can’t deny the existence of a deep bond between Africans and Europeans,” Gunst explains. It’s a way of thinking that fits with Gunst’s own heritage, “We mixed-race people live with two cultures and between two parents. It would be unthinkable for me to choose sides. To hate the Flemish, would mean hating my own father, and so I’d also be hating a part of myself.”

Humour and self-deprecation

The conciliatory attitude in Gunst’s work has evolved and the rage that resonated in his earlier work seems to have subsided. For example, in the documentary N-ID: The Stigma of the Negro-Identity (2007), or the series of performances titled VELLER (2011-2013), Gunst slaughters a “negro”. Today he believes more in the power of humour and self-depreciation than in the radicalism of anger. Gunst explains, “I’ll always remain an activist, but I’m past the phase of wanting to offend. Rage doesn’t help; you drown in it; you become consumed by it; you lose clarity of vision on the situation. Having said that, I think it’s of the utmost importance that other artists assert their anger, so we can fight on different fronts. I fully support artists who demand a radical decolonisation, and refuse to wait any longer for the change and progress that has been promised for so long. I see my work as complementary to theirs. You can either position yourself outside of the system, or you can work within it, and continue to try and make a connection with the opposing party. I think we need both strategies.”

Supported by the Gent LOD Musical Theatre, Flandria will be the first time that Gunst uses the power of musical theatre to make his point.

Gunst himself opens Flandria with a reading before the performance slips into a musical ritual. The opera music, written by composer Benjamin Lycke, reinforces the many historical references, and soprano Emma Posman performs the role of the mystical bride Flandria. Her transformation follows Gunst’s personal experience. He invites his audience to make that same journey and to recognise and embrace one’s own hybrid identity. When that finally happens, real social and political change is within reach. “Once you learn to see your own identity from a multi-faceted perspective, you will look differently at immigrants around you,” says Gunst, “They are no different to us. They’re just part of the stream of migration that has been a natural phenomenon since the time of the earliest Homo sapiens.”

Flandria

FlandriaNow that an increasing number of BAME artists are coming to the fore, Gunst thinks that there’s an opening to raise that awareness. “We need to work hard now, talk lots, write lots, and produce lots,” says Gunst, “so that we can confront as many people as possible with the natural logic of transnationalism. I think there’s a momentum now that we must seize.”