A Façade of Decency. How the Netherlands Deals With Its Colonial Past

For the Netherlands, the year 1945 was not an end to its war history. The country started a ruthless war, lasting almost five years, against Indonesian independence. Dutch colonialism had a façade of decency about it, a façade that has endured long after the so-called “police actions”. Dutch tolerance extends only so far; there is still no room for issues that question the decency of the establishment. In 2020, seventy-five years after the declaration of Indonesian independence, it was high time for apologies to be made at the level of government, and for historiography and a national memory that is more inclusive.

The Hague, 14 September 2011. In a courtroom, fifty-eight-year-old cement worker and activist Jeffry Pondaag and his lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld tensely await the judge’s verdict. Three years earlier, through his foundation the Committee of Dutch Debts of Honour (Komite Utang Kehormatan Belanda, KUKB), Pondaag had accused the Dutch state, on behalf of eight Indonesian widows and one male survivor, of being accountable for the execution of their partners in the Javanese village of Rawagede. There, on 9 December 1947, according to Indonesian counts, Dutch soldiers shot dead 431 men.

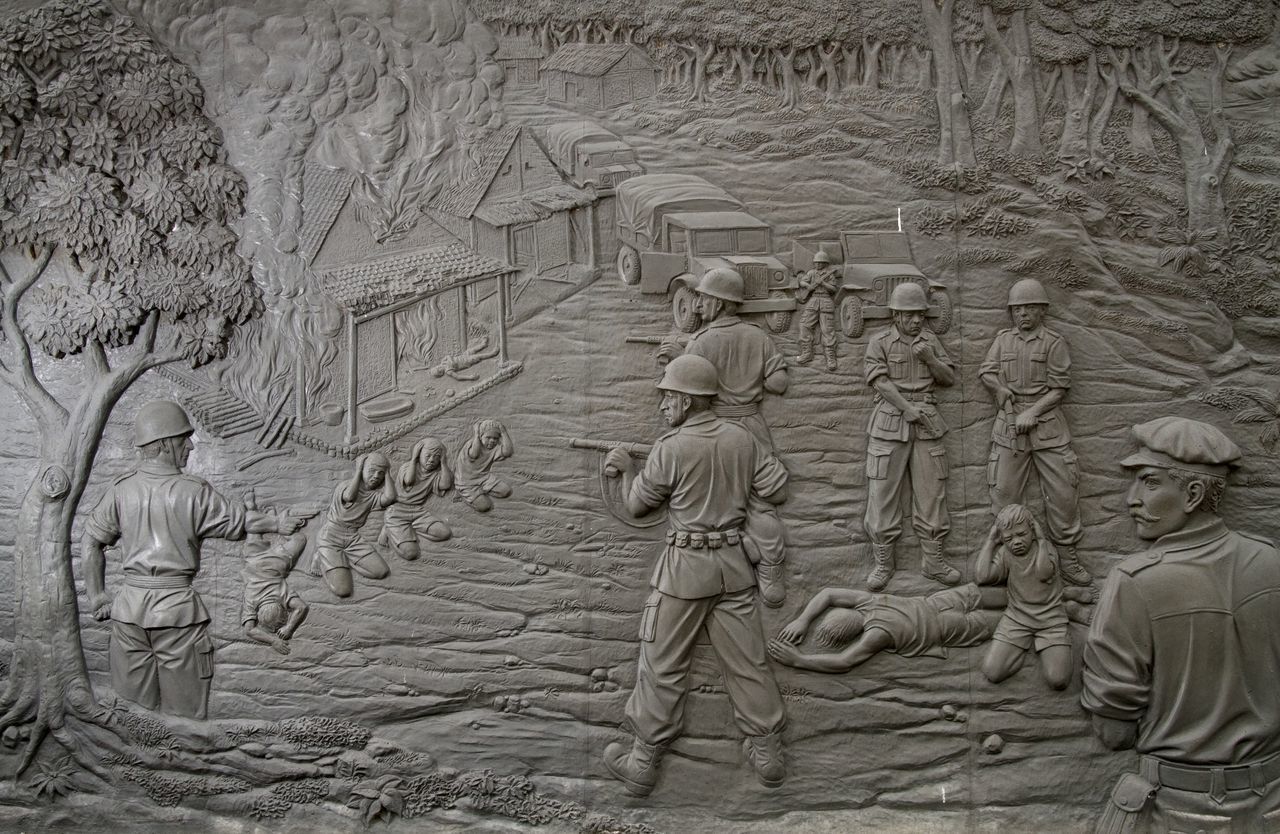

A mural at the Rawagede monument of independence depicts the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops.

A mural at the Rawagede monument of independence depicts the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops.The incident took place during the almost five-year war that the Netherlands waged against its former colony after Indonesia declared independence on 17 August 1945. In the Netherlands, the war was euphemistically referred to as “police actions”. Pondaag, the son of an

Indo-Dutch mother and an Indonesian father, in the years prior to the lawsuit had built a reputation for himself as the uncompromising thorn in the side of the establishment. He put the Rawagede case on the agenda, and with it the question of Dutch guilt in Indonesia.

The graves of Indonesian victims of the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops at the Rawagede memorial.

The graves of Indonesian victims of the 1947 massacre by Dutch military troops at the Rawagede memorial.On that autumn afternoon, sixty-four years after the crime, with only a handful of people present, the judge in The Hague delivered the ground-breaking verdict: the widows of Rawagede had been wronged. They were entitled to a state apology and to compensation for their suffering over the years. When the judge pronounced the ruling, the news took a while to register, sinking in for Pondaag only later, when he was approached by the media outside the court. At long last, recognition for the victims, he told the NOS news programme: ‘Their honour has been restored.’ After years of petitioning the Dutch state and lobbying the country’s historians in vain, the judge had thrown open the debate about colonial history for good.

“Good colonials”

Vergangenheitsbewältigung

(coming to terms with the past) – this is how Germany has addressed its fraught wartime history at the national level: subjecting itself to a thorough historical self-examination. With regard to its colonial past in Indonesia, but also in Suriname and the former Netherlands Antilles, such scrutiny never happened in the Netherlands, which resulted in an incomplete picture of Dutch identity. The judge’s ruling in the Rawagede case was at odds with the Dutch self-image of a tolerant nation. The belated awareness of a violent colonial past has meant that the Netherlands is only beginning to come to terms with that history now. At the same time, hardly any attention is allotted in the debate and historiography to the long freedom struggle as it was fought on the other side of the ocean. Postcolonial and Indonesian voices are still being side-lined, and exacting questions are often ignored. This typifies the notion of Dutch tolerance: it does not accommodate issues that question the decency of the establishment. This is central to the difficulty in handling the colonial past, which Pondaag also encounters in his struggle for recognition for Indonesian victims.

The belated awareness of a violent colonial past has meant that the Netherlands is only beginning to come to terms with that history now

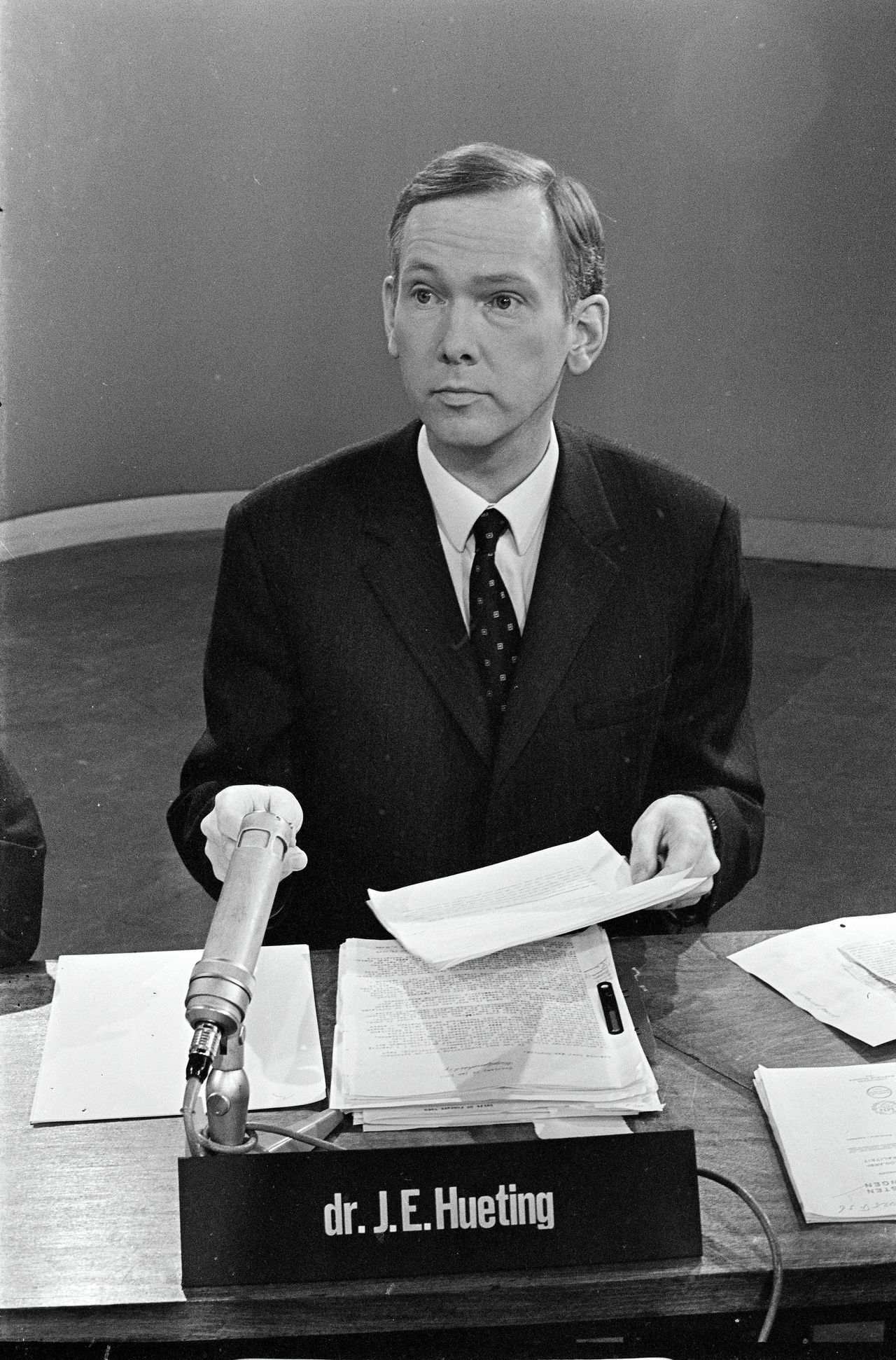

By his own account, Pondaag got lucky when he arrived in the Netherlands from Jakarta in 1969 at the age of sixteen. After twenty years’ silence on the matter, earlier that year war veteran Joop Hueting had appeared on national television saying he had witnessed and was guilty of war crimes in Indonesia. It was like a bomb exploding. Hueting had to go into hiding with his family because of the numerous threats he received from East Indies veterans. Never before had the Netherlands been so directly confronted with the flipside of 1945: the Dutch people saw themselves as victims of war by the German occupiers, not as perpetrators in Indonesia.

The Dutch military Joop Hueting gained national fame in 1969 because he spoke openly about war crimes committed by Dutch soldiers in Indonesia.

The Dutch military Joop Hueting gained national fame in 1969 because he spoke openly about war crimes committed by Dutch soldiers in Indonesia.The commemoration of 1945 was about “never again”, about peace, coal and steel, the idea that liberal democracy had finally won out in an economically united Europe, not about asking fundamental questions about one’s own identity. But the historical interpretation of “never again” is inextricably linked to the role played by Europe in its colonies. The image posited by Hueting hit extra hard because the Dutch saw themselves as “good colonials” in the Indies. Few Dutch people know that in 1933, when Hitler came to power in Germany and to everyone’s horror locked up his political opponents, Surinamese nationalist Anton de Kom and Indonesian nationalist Sukarno were being banished for their political views in the Dutch Indies. Indonesian freedom fighters were simultaneously silenced by the hundreds in camps in intolerable places such as Boven-Digoel in New Guinea.

Indonesian freedom fighters were simultaneously silenced by the hundreds in camps in intolerable places such as Boven-Digoel in New Guinea

Hueting’s statement of guilt in 1969 caused a great deal of controversy amongst veterans. Pondaag’s Indo-Dutch uncles who had served with the KNIL (Royal Dutch East Indies Army) were furious. The Indo community had come back traumatised, their history scarred by the Japanese occupation of Indonesia during the Second World War and the Bersiap, a revolutionary period in which Indonesian youths killed thousands of mixed-race and pro-Dutch people. For the veterans, the Indonesians had been “terrorists”. ‘I was called a murderer right here on the street for being Indonesian,’ says Pondaag. ‘But were we not liberated on 17 August 1945?’ he had asked his Dutch family incredulously. The official Dutch interpretation is that Indonesia only became independent when the Netherlands transferred sovereignty on 27 December 1949, a date that means next to nothing in Indonesia. Accordingly, the question of who the inhabitants of the Indonesian archipelago were in the period between 1945–1949, and what consequences this entails – a question that Pondaag regularly asks during public debates – still leads to upset in the Netherlands.

Hueting’s disclosure in 1969 was followed by the so-called Excessennota (Note on Excesses), an inventory hastily drawn up by the government of violent acts committed by Dutch military personnel, which concluded that these were merely isolated incidents. The lid was closed again. Three years later, in 1971, a statute of limitations was even instituted, a criminal law stipulating that war crimes could not expire, with the exception of those committed in Indonesia by Dutch soldiers in the period 1945–1950. The law was thus used politically to prevent Dutch people from being tried of war crimes in Indonesia.

Everyone knew, but no one could say it

The other side of Liberation in 1945 – the brutal war waged by the Netherlands against the independence of Indonesia, and its aftermath – also remained underexposed in academia. Historians asked few questions and people went along with the political refusal to address the subject. Writer Rudy Kousbroek (1929–2010), interned as a child in Japanese camps in the Dutch East Indies, denounced Dutch historians who, in his view, consciously noted only the unblemished parts of history and skilfully avoided the more tarnished pages. A famous clash between Kousbroek and the Leiden historian Cees Fasseur – who had compiled the Note on Excesses as a civil servant in 1969 – exposed how the academic establishment was skirting the issue. The two clashed about the 1904 Rhemrev Report, a government-commissioned and then covered-up report on the atrocities committed against contract coolies on the east coast of Sumatra, which was only dusted off in 1987 by the sociologist Jan Breman.

Cees Fasseur / Rudy Kousbroek

Cees Fasseur / Rudy Kousbroekphoto Kousbroek © Wim Ruigrok

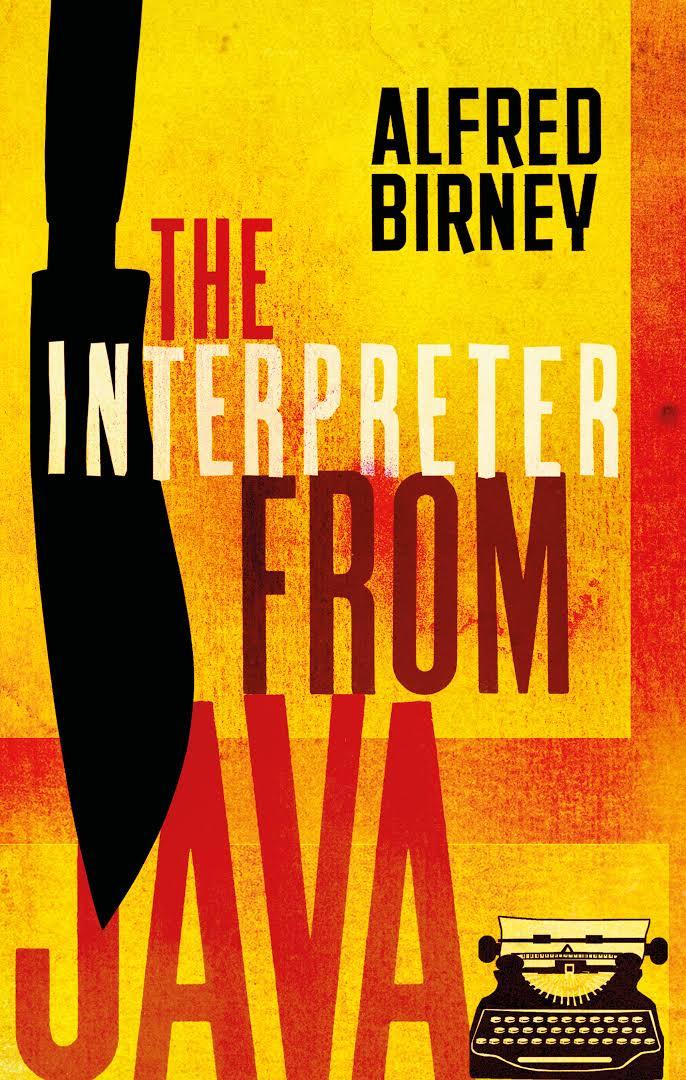

What troubled Kousbroek most about the report was the attitude of the parliamentary minister back in 1904 who had ridiculed the speakers quoted in it, knowing full well that in reality the abuses were much worse. ‘It is that mentality, that feigns innocence of murder, that façade of decency I have come to regard as the most miserable aspect of colonialism,’ he wrote in his book Het OostIndisch Kampsyndroom (The East-Indies Camp Syndrome; 1992). Kousbroek reproached Fasseur for knowing about the report, but having done nothing about it. Fasseur claimed that the archive was publicly accessible. This was the mainstream defence of the establishment when it came to the violent colonial past. It was mostly via the media and literature such as Alfred Birney’s De Tolk van Java (The Interpreter from Java) that a different reality became apparent, while independent researchers were often dismissed as incompetent or activist.

The Interpreter from Java by Alfred Birney

The Interpreter from Java by Alfred BirneyIt later transpired that the very same Fasseur had kept an important report on Dutch war crimes in his attic for a long time. The Swiss-Dutch historian Rémy Limpach (Netherlands Institute for Military History), formerly an independent researcher, was the first to state, in his 2015 dissertation at the University of Bern, that the excessive violence in Indonesia had not, as the Note on Excesses claimed, been incidental but rather structural. A conclusion that the historical establishment had not dared to voice, but which Fasseur – who avoided the subject himself as a professor at Leiden University – would call “obvious” in his memoir Dubbelspoor (2016). Everyone knew, but no one could say it, he said, displaying precisely that mentality, that façade of decency, which Kousbroek had attributed to the colonial system.

It will not have been a coincidence that Fasseur accompanied former Queen Beatrix as an adviser during her state visit to Indonesia in 1995. The occasion offered a chance to recognise Dutch moral failings as well as Indonesian independence, but it turned out to be a denial of both. Although she had been invited by the Indonesian authorities to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Republic of Indonesia, the Queen was absent on 17 August, arriving a few days later. Her absence was especially painful because the Dutch TV channel RTL had aired a documentary about the Rawagede massacre just days before. During the visit, the monarch subsequently did not mention the moral failings of her country, but spoke to Indonesians about their own handling of human rights. Pondaag, on the other hand, had deliberately decided to be in Jakarta with his family that day in 1995. ‘I wanted my children to understand the significance of 17 August for Indonesia.’ They learned very little about it at school, says Pondaag. And it is their in his view inadequate history lessons that prompted him to speak out about this history. The airing of the documentary about Rawagede was the deciding factor for him to visit and start campaigning for recognition of Indonesian victims. But the Netherlands would not hear his case.

Persistent misunderstanding of Sukarno’s struggle

Jeffry Pondaag

Jeffry PondaagIn 2005, sixty years after Indonesia’s independence, Pondaag founded the Committee of Dutch Debts of Honour on 5 May, a reference to the Japanese debts of honour and to Liberation Day, ‘to emphasise that Dutch war history did not end in 1945’. In August of the same year, during the Indies war commemoration in The Hague and then in Jakarta, Ben Bot, the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, said that the Netherlands had been ‘on the wrong side of history’ and that the date of Indonesian independence was accepted ‘politically and morally’. It was the first time that a moral statement had been made by the Dutch government regarding the past in Indonesia. But what exactly did Bot’s words mean, and for whom? In March 2020 a great gesture finally came from a head of state: an apology for excessive violence by King Willem-Alexander in Bogor. Although it is an important step, it still leaves many issues untouched. The societal discussions about the colonial past are thus not tied off yet.

These faltering attempts to relate to the colonial past highlight the focus on one’s own national history. That focus has shuttered off the Indonesian ideas about freedom, change and resistance. A few years ago, Pondaag started dressing up as Sukarno in a white suit with a black peci cap, and he now regularly appears like this when campaigning in public. It is a political statement. ‘Sukarno has never been accepted here in the Netherlands.’ The total absence in the Dutch public debate of Sukarno – the patriarch of the Indonesian nation – is striking, and reflects the Dutch incomprehension of the long struggle for independence.

Sukarno, Indonesia’s first president

Sukarno, Indonesia’s first presidentOn 17 August 1933 – twelve years before the declaration of independence – Sukarno was interrogated in Bandung, on the orders of the Council of the Dutch East Indies, for writing the pamphlet Mentjapai Indonesia Merdeka (“achieving Indonesian freedom”). In the police report drawn up of his arrest, Sukarno defended his cause: a free Indonesia was a legally justified struggle, ‘similar to the workers’ struggle in Europe.’ His interrogator likened the freedom struggle to the antics of a child who wanted to be released from ‘parental authority,’ as an expression ‘of hatred for the parents.’ Sukarno remarked that unlike children, Indonesians were not born of the government, whereby he captured the essence of Dutch paternalism. He was banished by the Governor General.

The unfamiliarity with Indonesian nationalists and their ideas of freedom caused persistent misunderstanding. During the war of independence, a military doctor on the demarcation line in Java had already warned, in a letter sent to the Dutch mission in Jakarta, that the lack of political awareness among the Dutch military was leading to atrocities against Indonesians. The soldiers made statements such as: ‘Sukarno is just like Mussert, a collaborator: get rid of him!’ They did not believe him when he explained that Sukarno, Sutan Sjahrir and many others had been imprisoned for decades. The doctor tried to explain the sustained rejection of Dutch authority by the Indonesians; this message never arrived in the Netherlands. Nearly seventy years later, Indies veterans still burst out in rage when they hear the name “Sukarno”. The first Dutchman to interview Sukarno was the journalist Willem Oltmans in 1956. The two became friends, in response to which the Dutch government thwarted his career for a long time. With his white Sukarno suit and black peci cap, Pondaag counterbalances the dominant narrative in the Netherlands in which the struggles of Sukarno and of many other Indonesians, which preceded 1945 by far, are still ignored.

Colonialism in crisis

Pondaag’s action of drawing public attention and debate to a colonial problem via a costume does not stand alone. In 2011, the same year as the court’s ruling on Rawagede, Quinsy Gario, an artist and activist with a Curaçao background, printed “Black Pete is racism” on his shirt during the annual festivity of the arrival of Sinterklaas, which took place that year in Arnhem. The white saint’s black helper had always been explained in the Netherlands as a sooty chimney sweep, but Gario stated that Black Pete depicted a slave and should no longer be represented as such in this day and age. Racism and the history of slavery were put on the map in one fell swoop and it led to a fierce social debate. Again, it was not the historical establishment but activist voices from the postcolonial community that set the agenda.

Quinsy Gario wearing the shirt 'Black Pete is racism'

Quinsy Gario wearing the shirt 'Black Pete is racism'But even though the call for polyphony is getting louder and louder, there is another that harks back longingly to colonial times, to the good old days. For example, Thierry Baudet, the leader of the radical right-wing political party Forum for Democracy, paints a positive colonial past with seventeenth-century Dutch flagships booming in the surf. Shining a light on a glorious, but one-sided past is a hallmark of the international rise of authoritarian politics: Trump is making America “great again” and Putin is looking for the “primeval” Russian.

By making a distinction between population groups, as Baudet also does, he upholds the core of the colonial system. Baudet’s concerns about “uprooting” in politics, which he targets against newcomers, stem from his self-confessed Dutch Indies background, where themes such as uprooting and nostalgia were important. For example, in 2018 he contended in the Dutch Indies monthly magazine Moesson (Monsoon) that the Netherlands should never have given up Indonesia and should only apologise for one thing: ‘that we gave free rein to the criminal regime of Sukarno’. For him, Sukarno is the criminal who took the beautiful colonial times away from his family, who uprooted people, synonymous with the threat of strangers now standing at the gates of Europe.

Thierry Baudet

Thierry BaudetThe meanwhile highly polarised Dutch colonial debate was recently described by Ariel Heryanto, professor of Indonesian Studies at Monash University, in the NRC Handelsblad newspaper, as “colonialism in crisis”. In 2016, after persistent social pressure, the Dutch state released money for a four-year historical inquiry into Dutch conduct in Indonesia in the period 1945–1950, which after all this time was an important step forward. The social debate has since shifted from the national-centric Vergangenheitsbewältigung to the “decolonisation” of historiography, public space, museums, education and commemorations. British academic Priyamvada Gopal explains decolonisation as a process whose main purpose is to understand more of other people and cultures. The use of violence has been shrouded in silence, but so have the Indonesian views, and this shows how the colonial attitude still prevails. It is this lack of multi-perspectivity in dealing with the colonial past that the Netherlands continues to struggle with. The National 4 and 5 May Committee, which organises the annual commemoration of the Second World War, has so far been unable to bridge the gap from “never again” to the flipside of 1945, to Indonesia, and in the national historiography, the Dutch voice still dominates the narrative.

(continue reading below illustration)

© Trui Chielens

The repositioning of landmarks

On 27 June 2019, Pondaag once more found himself in court in The Hague, alongside his lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld. The Dutch state had appealed against the ruling in the case of Mr. Yaseman, now deceased, who had been tortured by Dutch soldiers in a prison on East Java in 1947; the judge had ruled in his favour and awarded him a sum of €5,000. Also present that day were the children of two victims of the executions by Dutch soldiers in South Sulawesi; they too sought justice. The session coincided with the opening by King Willem-Alexander of the Sophiahof in The Hague, a museum established in memory of the Dutch East Indies. Outside, the relatives of Indo-Dutch soldiers, who have been fighting for decades for the unpaid wages of their husbands and fathers during the Japanese occupation, were protesting. The Indo-Dutch community does not feel heard, while one of the main defences used by the Dutch state in court was that the reliability of Indonesian witnesses is poor. Once again, it is this persistent refusal to listen to people’s testimonies, in the knowledge that Yaseman’s torture was one of at least tens of thousands, if not many more, that makes the façade of decency noted by Kousbroek painfully tangible.

It is time for the Netherlands to acknowledge the crime committed by the Netherlands in waging war against the young nation

On 17 August 2020, it will be seventy-five years since Sukarno, together with Mohammed Hatta, proclaimed Indonesian independence. It is time for the Netherlands to graciously recognise this date and history. The legacy of the colonial past cannot be tied off simply by apologies at government level. What is at stake really is the enduring space that will have to be provided for various voices, and for critical debate that questions the decency of the establishment. Only this can reposition the landmarks of the colonial legacy to allow for historiography and a national memory that is more inclusive.

This article is the English translation of Een façade van zindelijk fatsoen. De Nederlandse omgang met het koloniale verleden, published in the book Nulpunt 1945 (Zero Point 1945, Ons Erfdeel vzw, 2020).