A Garden Full of Symbols. Flora in the Paintings of Van Eyck

From daisies to columbines, no fewer than 76 different flowers and plants have already been identified on the Ghent Altarpiece. And all that greenery is rich with significance. This masterpiece by the Van Eyck brothers depicts a luxuriant garden of symbols and allegories.

All creatures of the world

Like a book and like a painting

Are like a mirror for us:

Our life, our death,

Our condition, our fate

All are minutely inscribed.

Alan of Lille, theologian, poet and Cistercian monk (ca. 1120 – 1202)

The Garden of Paradise depicted in The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb

The Garden of Paradise depicted in The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb© Art in Flanders, photo KIK-IRPA

The Garden of Paradise depicted in The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, on the central panel of the Ghent Altarpiece, contains a large variety of plants but is essentially a garden full of symbolism. Christian church fathers and medieval thinkers loved biblical allegorical images of plants. In the works they wrote in Latin or Greek, they regularly used plant imagery. Often this goes back to Biblical texts like the Song of Songs (or Song of Solomon) and the book of Ecclesiastes. From the 13th century onwards, more and more allegorical plant imagery appeared in vernacular literature. It is logical, therefore, that the Van Eyck brothers would make full use of it on the Ghent altarpiece.

Part of the Garden of Paradise after restoration

Part of the Garden of Paradise after restoration© Art in Flanders

The Garden of Paradise, for example, is depicted with numerous evergreen plants, which symbolise immortality. On the other hand, the spring bloomers in this paradise represent Christ’s resurrection and faith in his rising from the dead. The abundant medicinal herbs on the altarpiece stand for the healing power of faith and the forgiveness of sins. Indeed, in the Middle Ages, such herbs not only helped against illness they were also often a symbol of the healing powers of God and Christ. In the imagery of the church fathers and other medieval Christian thinkers, God and Christ were the ultimate healers. Moreover, the role of the Virgin Mary was gradually becoming more important too.

Mary plants

In the early Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary was a rather minor figure in Christianity. From the 11th century onwards, however, her veneration increased. In particular, the influential Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153), a Cistercian abbot and church reformer, played a major role in the development of the Marian cult. Partly under the influence of his Sermons on the Song of Songs, Mary began to be considered as the most important mediator between mankind and God. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the growing cult of Mary was also translated into allegorical imagery. Because the imagery of the Song of Songs was applied to Mary as a heavenly bride, she is often depicted in an enclosed garden or hortus conclusus. And in that garden grew plants which, analogous to the texts of the church fathers and other Christian thinkers, the medieval poets associated with her over and over again.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna at the Fountain, 1439, KMSKA Antwerp

Jan van Eyck, Madonna at the Fountain, 1439, KMSKA Antwerp© KMSKA

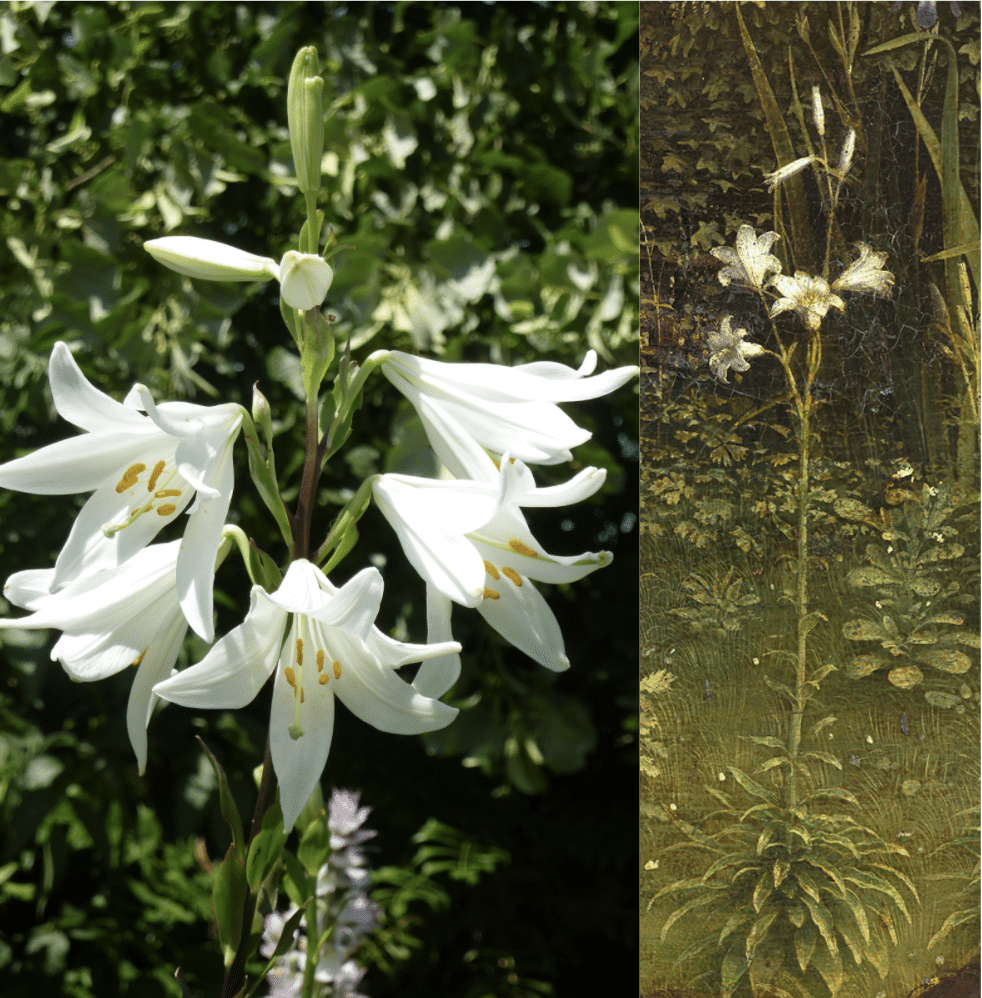

Jan van Eyck uses the same imagery in the hortus conclusus of his Madonna at the Fountain (1439: KMSKA Antwerp). Indeed, on this panel we only see Mary flowers: French roses, daisies, March violets, blue irises, columbines, lilies of the valley and a type of peony. In the garden in the Virgin of Chancellor Rolin (ca. 1435, Louvre Museum Paris), Mary plants also grow. Clearly recognisable are his blue irises, a type of peony, a cultivated variety of the French rose and, above all, the Madonna lilies, the symbol par excellence of purity, innocence and virginity.

Madonna lilies are the symbol par excellence of purity, innocence and virginity.

Madonna lilies are the symbol par excellence of purity, innocence and virginity.© Wikimedia Commons / Art in Flanders

Above all, however, the Garden of Paradise in the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (1432) teems with plants symbolising Mary. Besides those already named, we also find garden marigolds, wild daffodils, summer violets, spotted lungwort, Lady’s bedstraw, Lady’s mantle and, amongst the shrubs, pomegranate. Every one of these species is also documented in medieval texts as a Marian plant, including in a series of poems in Middle Dutch. Some examples are an anonymous hymn, Onser vrouwe bloemengarde, about Our Lady of the flower garden, a hymn about the VII flowers (de VII bloemen), and a poem written by Jan Praet, a poet from Bruges, ca. 1400. In his Sp(i)eghel der wijsheit (Mirror of Wisdom), the latter attributes five virtues to Mary using flower allegories. The daisy represents mercy, columbine humility, the marigold faithfulness, the Madonna lily purity and the rose love.

Marigold

Marigold© Art in Flanders / Wikimedia Commons

We know of other Mary plants thanks to their medieval names, lac benedictae virginis (milk of the Blessed Virgin), for example, for lungwort. Another example is the common columbine, with its medieval name Our Lady’s shoes. Some contemporary plant names still point to the medieval tradition of naming plants after the Virgin Mary, like lady’s mantle, which used to be known as Our Lady’s mantle, or Our Lady’s bedstraw for sweet woodruff. Lungwort is also still referred to variously as Our Lady’s milk, milk drops, or Our Lady’s milk drops.

Tansy

Tansy© Art in Flanders / Wikimedia Commons

A special case in the Garden of Paradise depicted in the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb is the tansy, which has been used since the Middle Ages in the herbal bouquets that are consecrated on the feast day of the Assumption of Mary. This custom is still found in the Belgian-Dutch Meuse region, the area from which the Van Eyck brothers most probably come. The 9th

century Benedictine monk Walahfrid Strabo referred to tansy as ambrosia, which means immortal or immortalizing.

Christ plants

As already mentioned, all medicinal herbs are, according to medieval tradition, symbols for Christ, i.e. Christ plants. Those on the Ghent Altarpiece can also undoubtedly be understood as such. But make no mistake, many Mary plants can at the same time symbolise Christ, as well. That is the case, for example, of the lily of the valley (Lilium convallium), whose downward bending flowers are a symbol of humility,

a virtue the Virgin Mary and Christ shared. A common name for this plant, since medieval times, is Our Lady’s tears or Mary’s tears.

Many Mary plants can at the same time symbolise Christ

Flowering plants of the crucifer family, such as wallflowers and summer violet, are thought to symbolise Christ’s crucifixion. Typical of this family is the four-petal flower, in which the pious in the Middle Ages could discern Christ’s cross. On the polyptych, for example, we find the wallflower in two places on the rocky outcrops in The Just Judges panel and in The Knights of Christ. On the central panel, The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, we find halfway up on the far left a white and, a little further to the right, a light blue form of summer violet.

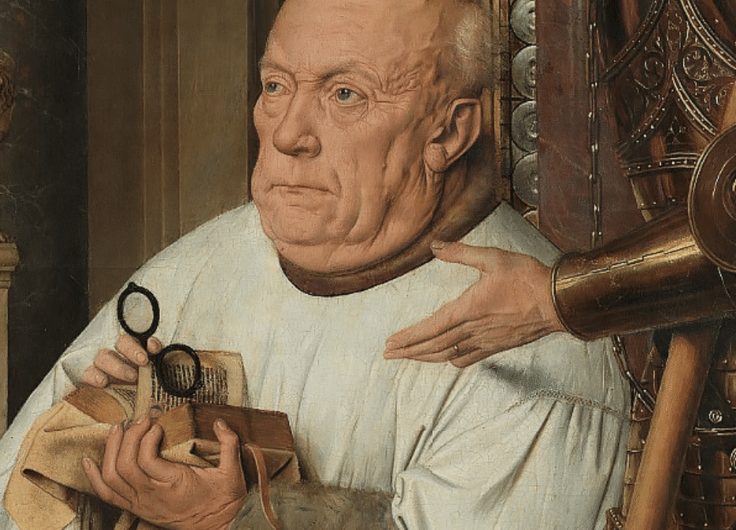

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon Joris Van der Paele, 1436, Groeninge Museum, Bruges

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon Joris Van der Paele, 1436, Groeninge Museum, Bruges© Groeninge Museum

Later, in the painting Madonna with Canon Joris Van der Paele (1436, Groeninge Museum Bruges) Jan van Eyck would use both colour varieties of the summer violet even more clearly as Christ plants. On this panel the Christ child gives a posy of flowers to Mary. In addition to the summer violets, this posy of sweet-smelling flowers contains a few red carnations, which used to be called nail flowers in the vernacular. The shape of the carnation flower is something like an old-fashioned forged nail. They are used, therefore, to symbolise the crucifixion of Christ and the nails of the cross.

Symbolism for advanced students

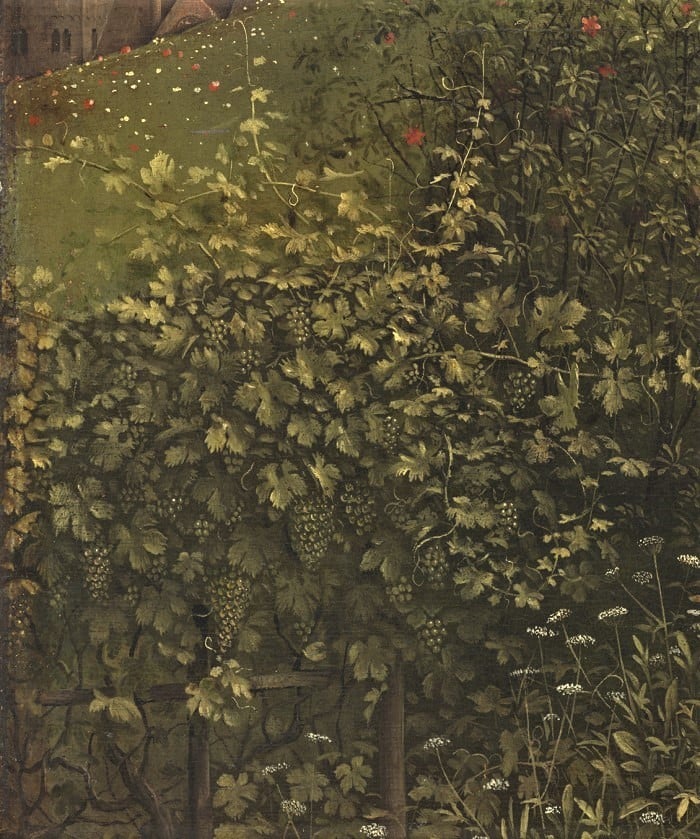

The visual language of some plants can have multiple meanings, even on one and the same work of art. A striking example of this is the vine, or grapevine, that appears several times on the altarpiece.

For those who look at the Ghent Altarpiece

today and know something of the Bible, there can be no more obvious Christ plant than the vine.

Vine on the central panel of the Ghent Altarpiece

Vine on the central panel of the Ghent Altarpiece© Art in Flanders

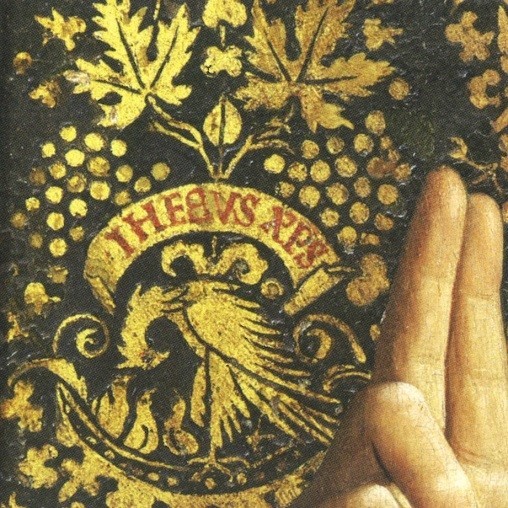

After all, did not Christ say of himself, “I am the true vine” (John. 15:1)? It is immediately clear, therefore, that the vine is the symbol par excellence of Christ, and the branches of the vine represent the faithful (John 15:5).

© Art in Flanders

On the back carpet of the enthroned God the Father, we see above the pelican, which brings its dead young back to life by sprinkling them with its blood, a vine under which the name of Jesus Christ stands. The imagery could not be clearer.

In the central panel, however, another symbolic interpretation of the vine is also possible. In medieval Christian symbolism, Mary is represented as a vine and Christ as a bunch of grapes. Mary as a vine is a reference to the book of Ecclesiastes

(24:17) and more particularly to the Song of Songs. The bunch of grapes, which will later be crushed in the wine press, are used there as a symbol of Christ’s blood, which was shed for mankind. Similar imagery appears in works by influential figures such as Bernard of Clairvaux and the Cistercian Abbot Adam of Perseigne (ca. 1145-1221). Dirc of Delf, an influential Dominican and a contemporary of Van Eyck, used similar imagery.

Finally, a third interpretation is also possible. If the passage from Ecclesiastes applies entirely to Mary, then the vine is only a Mary plant. This imagery can be found, for example, in a text from the Limburg Sermons (ca. 1300).

Number symbolism

On the Ghent Altarpiece there are also many examples of Christian numerical symbolism, which was still very widespread in the Middle Ages.

Lilies of the valley on Mary's crown

Lilies of the valley on Mary's crown© Art in Flanders

Take three, for example. Three is the number of the soul in Christianity. Theologically it stands for the Trinity (the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit). It also corresponds to the number of days Christ spent in the Tomb and to the number of divine virtues (Faith, Hope and Charity). That makes it a very important number. As a symbol, we find it in plants with trifoliate leaves, such as the numerous wild strawberries and white clover in the green meadow of the central panel. Some plants were even adapted by the Van Eyck brothers. The lilies of the valley on the central panel have three clusters of white hanging flowers and they display the same peculiarity on Mary’s crown. In reality, however, they bear only a single cluster.

Seven is also clearly depicted in some other plants, especially the Mary plants. The number seven can symbolise the seven sorrows and the seven joys of Mary or seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, or even the seven days of creation. In the Roman Catholic tradition, it can also refer to the seven virtues.

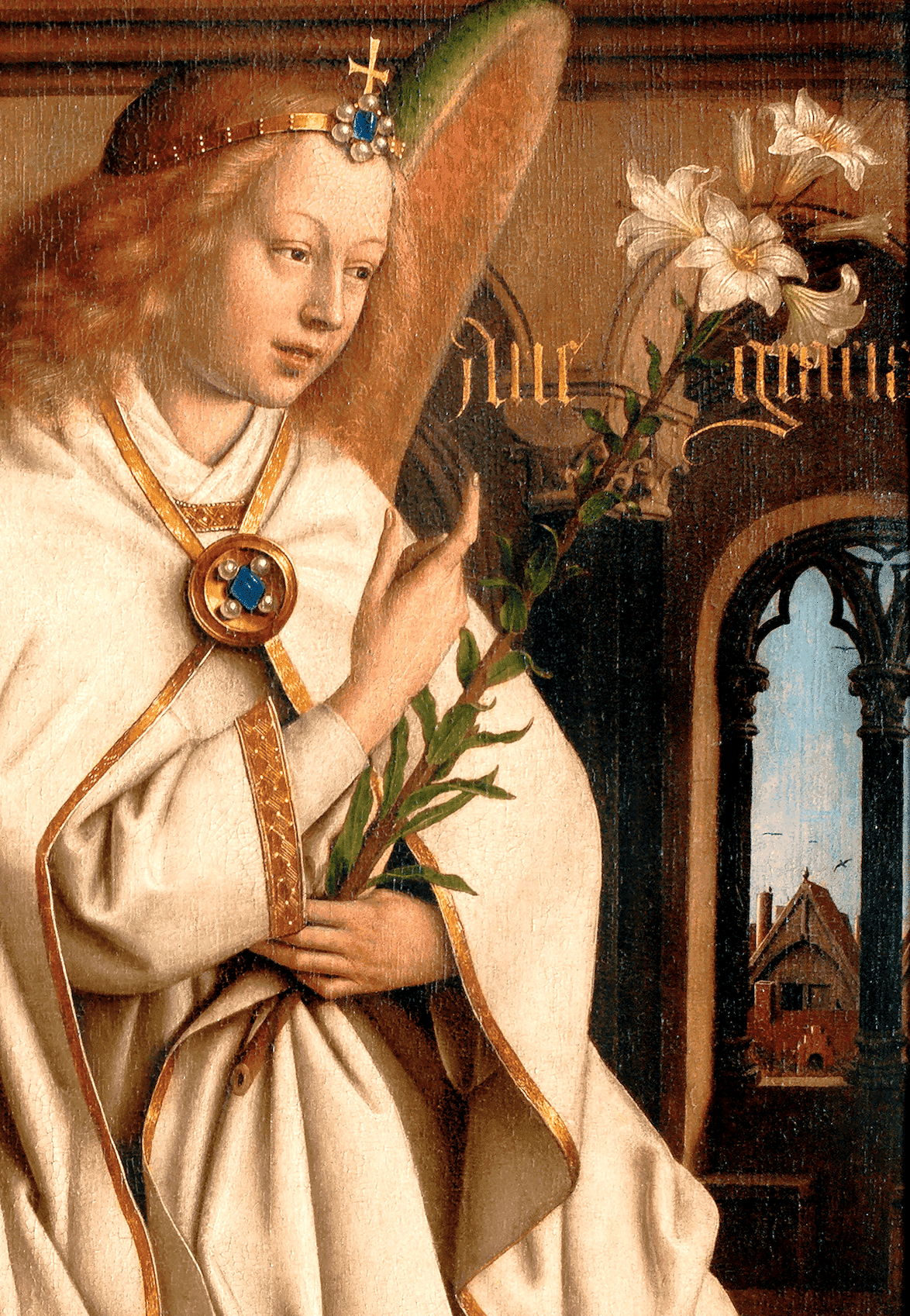

The archangel Gabriel holding Madonna lilies

The archangel Gabriel holding Madonna lilies© Art in Flanders

Once again, the Van Eyck brothers gave nature a bit of a helping hand. The lily of the valley is systematically depicted with seven leaves on the Ghent Altarpiece, yet in reality the plant has only two leaves. Another example, the flowering white lily or Madonna lily not only has seven flowers on the central panel, but also on the panel with the archangel Gabriel. On both panels there are four flowers in full bloom and three that have not yet opened completely. Do these white lilies perhaps refer to a statement by the church father Augustine that the number three refers to the spirit (the soul) and the number four to the material (the body)? Or is this mere coincidence?

Jewish symbols?

Professor Luc Dequeker, emeritus professor of Jewish Studies (KU Leuven), posits in his book on the mystery of the Ghent Altarpiece (Het Lam Gods, 2011) that the polyptych represents the universal redemption of man at the end of time and was inspired by the Jewish question.

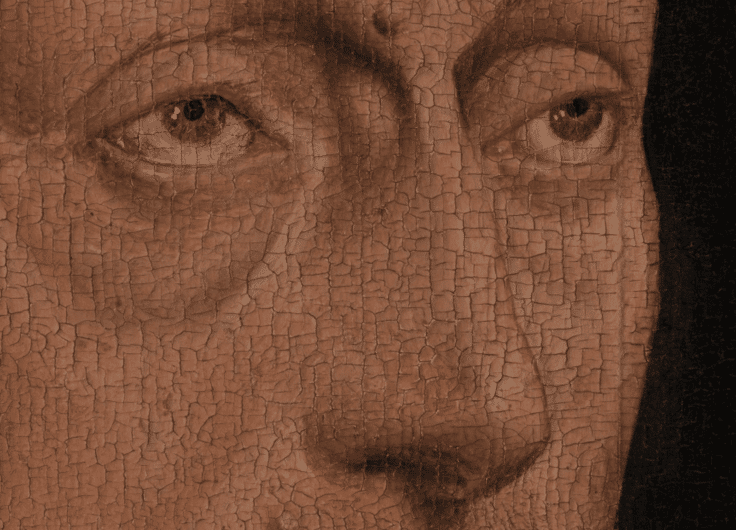

The poet with the Adam’s apple or Jewish etrog

The poet with the Adam’s apple or Jewish etrog© Art in Flanders

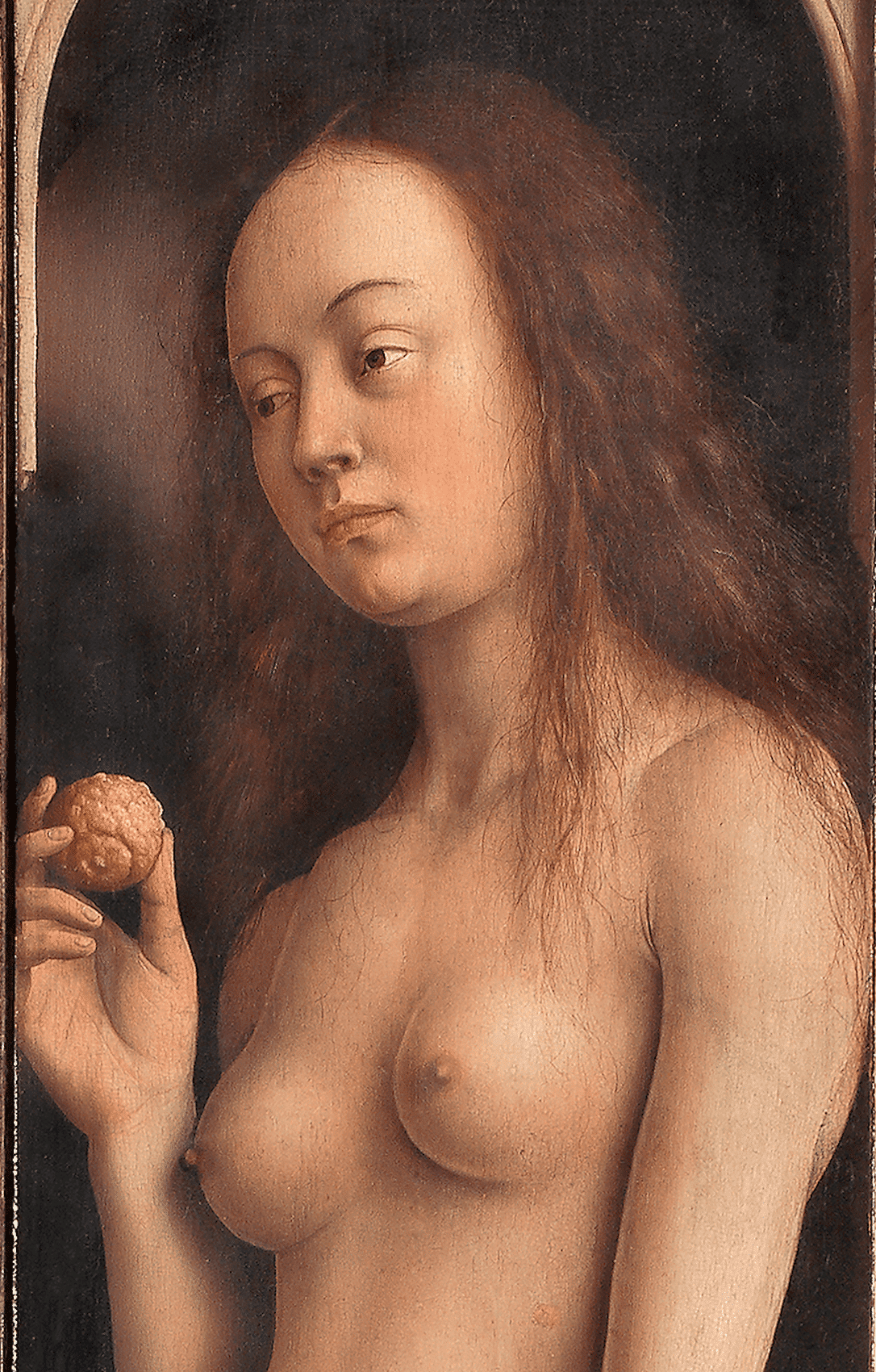

The so-called “celebrated poet with white cloak”, in the central panel, is said to be a representative of the Jewish nation. He does indeed have a Jewish symbol in his hands, the Adam’s apple or Jewish etrog, a citrus fruit that may symbolise the Jewish feast of Tabernacles, or Sukkot. A contemporary of Van Eyck, the Flemish mystic Dionysius the Carthusian (ca. 1402-1471), compared the picking of the etrog with the acceptance of redemption through Christ. The Adam’s apple in Eve’s hands then probably refers to Mary as the new Eve and to Christ as the new Adam.

Eve holding an Adam's apple

Eve holding an Adam's apple© Art in Flanders

To the left of the “celebrated poet” stands a man with a somewhat hidden willow branch, which may also be a reference to the Jewish Feast of Tabernacles.

In the same group, in front, stands a man with a blue cloak. He is holding a green branch, a cut-off olive branch, and he seems to be about to graft it. The apostle Paul used the cultivated olive tree from which branches have been cut, as an image for the Jewish people that had remained faithful to Christ and his prophets.

© Art in Flanders

For the elite or for ordinary people?

The above might lead one to conclude that plant symbolism could only be understood by Bible specialists. In the Middle Ages, however, plants were part of ordinary people’s everyday culture. Even before the birth of Christianity, plants were regarded as animated creatures that should be approached with the greatest caution, for they harboured hidden meanings. The art was to decipher them and use – or misuse – them. With the advent of Christianity, plants were also finally Christianised and acquired a new symbolism for use by the faith. Try it for yourself, look carefully at the columbines on the Ghent Altarpiece. Can you see the doves, God’s messengers in the Christian faith and symbols of the Holy Spirit?

‘In Search of Paradise: Flora on the Ghent Altarpiece’, Ghent, Province of East Flanders, 2020, 295 pages