A Gem for Enthusiasts: ‘The Land Between the Languages’ by Stefan Zweig

Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) liked to visit Belgium and did so frequently. His reportages on those visits have now been translated into Dutch and collected into a small, beautifully illustrated volume. The stories vary greatly in quality, revealing Zweig’s evolution as a writer, as well as his struggles with the Great War.

It is thanks to poet Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) that Zweig developed a penchant for Belgium, and in particular for the (artistic) cities, early in his writing career. As a student, Zweig had come into contact with Verhaeren’s poetry. He considered Verhaeren as important to Europe as Walt Whitman was to American poetry and language, and he was, therefore, keen to translate Verhaeren from French into German. With that idea in mind, in his early twenties, Zweig travelled to Brussels in the hope of meeting the poet there, but that initially seemed a hopeless mission.

Stefan Zweig

Stefan ZweigWikimedia Commons

Until he visited the now almost forgotten sculptor Charles Van der Stappen, and to his great surprise Verhaeren dropped in. Zweig was delighted to hear that Van der Stappen was working on a bust of Verhaeren, and that during the final session, which coincidentally was to take place that day, he needed someone to converse with the poet for a couple of hours, to pass the time. Zweig described that first, instantly intense meeting in detail in his Erinnerungen an Emile Verhaeren (Memories of Emile Verhaeren, 1917), and later again in his masterful, posthumously published autobiography Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday, 1944). We also have that first book about Verhaeren to thank for the title of the recently published reportage book in Dutch Het land tussen de

talen (The Land Between the Languages): this is how Zweig described Belgium in his book on Verhaeren.

It is thanks to poet Emile Verhaeren that Zweig developed a penchant for Belgium

During that same first trip to Belgium, Zweig also visited Ostend and Bruges, which are the subjects of the first reports in the book. They are essays by an already erudite writer, but an inexperienced one. Zweig showcases his knowledge, but in contrast with his friend and contemporary Joseph Roth, he hardly pays any attention to significant detail, or to matters such as suspense. The piece on Ostend in particular is full of high-minded, general observations which might have applied to any worldly European seaside town. Only in the framework of a larger work, such as this book, does it have any value.

The first piece on Bruges suffers from the same shortcoming. Although here Zweig does something, in a modest form, which he later turns into one of his trademarks. He pairs reportage with the admiration he feels for works of art relating to the city. For instance that first essay on Bruges is also a story about his love for the painting of Hans Memling, a visit to an exhibition of works by the Flemish Primitives, and a modest ode to Georges Rodenbach’s Bruges–la–Morte. During his lifetime Zweig was to acquire fame among other things as a biographer of many artists, philosophers and politicians, such as Erasmus, Marie-Antoinette, Casanova, Stendhal and Tolstoy.

Zweig was European to the core, attaching no importance to borders

His second story about Bruges, written barely two years later, shows how Zweig has evolved as a writer. He is a little more graceful, and he ventures to air his own opinion from time to time, instead of constructing his stories mainly around the work of other artists, although Memling and Rodenbach are again mentioned. He describes Bruges as a city cut off from reality, a city as cold as a tomb. The picture he sketches is not especially cheerful, but the melancholy Zweig has pledged his heart to that silent Bruges.

Zweig continued to travel to Belgium in subsequent years and often spent his summers in Ostend and De Haan. He wanted to visit his new friends there, to talk about their work, as well as to give more attention to lesser-known artists of the French-speaking world in the German-speaking cultural sphere. Zweig was European to the core, attaching no importance to borders. In 1914, the first year of the war, he visited Liège, Louvain and Antwerp. The war is present in his essays but not prominent. Zweig struggled to speak out and was sometimes circuitous with the truth. He was reluctant to offend his German friends (or clients), nor did he wish to distance himself from his French-speaking and other cosmopolitan friends.

His almost lyrical description of the Menin Gate, the British pilgrimage site, is particularly beautiful

We might call it a lack of courage, but perhaps Zweig’s attitude in fact sprang from incomprehension: incomprehension of the violence of war, of people who do not distinguish between the culture and the leaders of a country. That Verhaeren of all people vehemently condemned the Germans and their culture, caused Zweig great sadness, but he would never abandon his friends. Zweig was a desperate humanist, who lived in part in an elite cultural bubble, with little eye for the geopolitical aspirations of government leaders and their military henchmen. It was the same hesitant attitude for which he was fiercely indicted in the run-up to the next world war by Roth, who accused Zweig of paying too little attention to the destructiveness of the Nazis.

In World War I Zweig eventually chose the side of the international pacifists, after encountering the group centred around the French writer Romain Rolland in Geneva, where he travelled for a performance of his play Jeremias. There in Switzerland, he made the acquaintance of the Flemish artist Frans Masereel, for whom he immediately exhibited great admiration. In The World of Yesterday he describes his friendship with Masereel as intimate, “with the tempestuousness you otherwise only have in childhood friendships”. He thought Masereel was the most heroic and gifted artist of the international group which was trying to counter the war propaganda in Switzerland through small publications. After the war, he was to travel to Paris regularly, where he always sought out Masereel.

An element of the pacifism stoked by Masereel and his associates resonates in the final report in this short collection, an essay written in 1928 about Zweig’s visit to Ypres. He had been there before, but now describes the World War I tourism affecting the town. His almost lyrical description of the Menin Gate, the British pilgrimage site, is particularly beautiful: “more impressive than all triumphal arches and victory monuments I have ever seen”. At the same time, he recognises the flipside of war tourism, calling it horrific how the living now gain from the dead, and that the carefree descendants can look upon the gruesome torments of half a million brothers so easily and in such a well organised form. It is undoubtedly the strongest essay, which also reveals how Zweig became a better, more fluent writer over the years, with a sharper eye for detail and the daily lives of ordinary people.

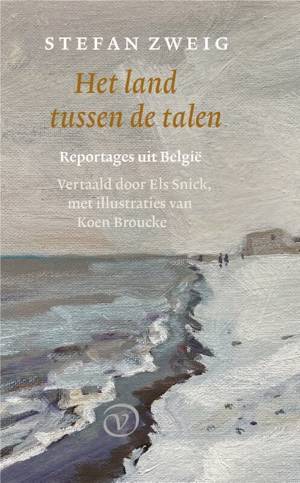

Ypres, oil on canvas, 2021. The illustrations by Koen Broucke wonderfully capture the melancholy, sometimes sombre mood of the stories.

Ypres, oil on canvas, 2021. The illustrations by Koen Broucke wonderfully capture the melancholy, sometimes sombre mood of the stories.© Koen Broucke

The Ypres article had previously been included in a different Dutch translation in De geschreven oorlog (The Written War, 2016), a publication by the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres. The stories in this collection are skillfully translated by Els Snick, who previously won her spurs translating the journalistic work of Joseph Roth and later brought his masterpiece Radetzkymars to a new readership with a fresh, contemporary translation. For Privé-Domein she also translated correspondence between Zweig and Roth, Elke vriendschap met

mij is verderfelijk (Every friendship with me is malevolent, 2019).

It is certainly not down to Snick that the first pieces in this collection of Zweig’s work make rather more awkward reading than the final story, which he wrote at a moment when he had reached full maturity as an author, a big literary name of his time. Zweig’s first reports have fared less well against the test of time than his later work, and the same goes for his short stories and novellas. The land between the languages is therefore primarily a gem for enthusiasts.

Nevertheless, there are two elements which absolutely lend this collection extra cachet. Firstly there are the magnificent illustrations by Koen Broucke, which wonderfully capture the melancholy, sometimes sombre mood of the stories. The illustrations are in black and white, further underlining the melancholy. Other than a lonely cyclist, there is also no human to be seen.

There is also an excellent afterword by Piet Chielens, former director of the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, an enthusiast and expert on Zweig’s work. He clarifies why Zweig had so much difficulty speaking out at the beginning of the war. He chose silence in the hope of preserving friendships and picking them up again as soon as the violence of war had subsided. Chielens also explains why Zweig intentionally remained unclear in his reports on Liège, Louvain and Antwerp, but cuts through the lies Zweig deployed at the time. Chielens refuses to impose a moral judgement, and rightly so, but from a distant sideline that would be all too easy.

Stefan Zweig, Het land tussen de talen. Reportages uit België, (The Land Between the Languages: Reportages from Belgium) Van Oorschot, Amsterdam, 2022, 96 pp.