A House as a Second Skin. The Documentary ‘Housewitz’ by Oeke Hoogendijk

Oeke Hoogendijk’s Housewitz is a documentary portrait of her mother whose phobias have kept her from setting foot outside her house for about three decades. Her cluttered upstairs rooms are full of “unprocessed junk.” A film about a house as a second skin: about security, being trapped and travelling in your imagination.

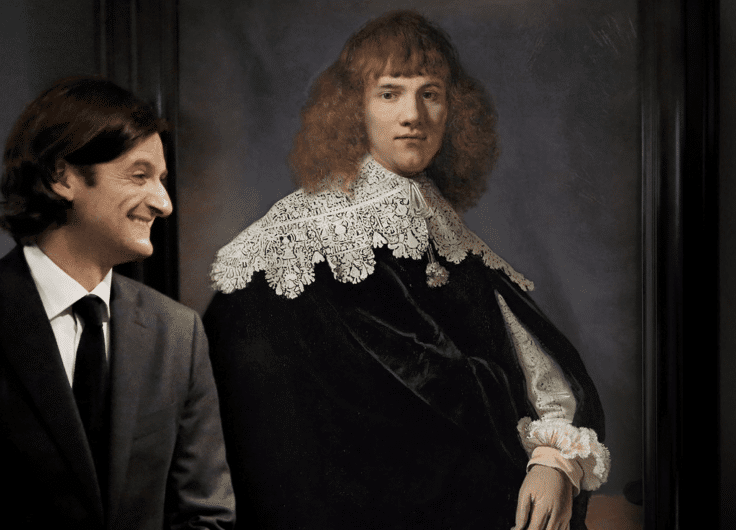

Oeke Hoogendijk

Oeke Hoogendijk© Annaleen Louwes

‘I’ve been to Iceland, South Africa and Colombia. I also want to go to Switzerland in the snow sometime, with this train.’ These words are spoken by Lous Hoogendijk-De Jong (1926 – 2020), mother of the perceptive Dutch documentary maker Oeke Hoogendijk (The New Rijksmuseum, My Rembrandt). Mother Lous is the subject of the portrait entitled Housewitz, which her daughter Oeke worked on for fifteen years. What makes the statement about the journeys made by mother Lous immediately intriguing is that they probably never physically took place. She stands in front of her television. Rail Away is on (also known as Die schönsten Bahnstrecken): her favourite programme, which shows hours and hours of images of trains and tracks from around the world. Is the TV her window to the world? Or is it perhaps a mirror as well?

Tracks appear to play a leading, deeply ambiguous role in this documentary portrait about a Jewish woman with a concentration camp past. Lous was once taken by train to the camps in Westerbork and Theresienstadt. Family members who were put on transport never returned. Tracks led to the destruction of her world. Tracks have left deep scars in her personal history.

Phobias have kept her from setting foot outside her house for some thirty years. Only at home does the elderly Lous still feel safe. But as an image on the television, the railway offers her an opportunity to escape: to go into the outside world, to travel, to experience new adventures. The reassuring, regular cadence of the metal wheels on rails lulls her to sleep, often only around three in the morning, or even later when things go wrong. She often dreams about going somewhere, but then not being able to get home. It is well past noon before she scrambles out of bed that is in the living room, flanked by a refrigerator, television, radio, and CD player.

Tracks play a leading, deeply ambiguous role in this documentary portrait about a Jewish woman with a concentration camp past.

Another line of contact with the outside world runs over the phone. When Oeke calls Lous, Lous invariably answers with: ‘Yes, it’s me.’ To which Oeke’s drily replies: ‘Yes, me too.’ It has a comical effect. Humour – always present in Hoogendijk’s work – is also in Lous’ creative arsenal of curses: ‘Bloody useless! Jesus Christ Superstar! I wish I would drop dead!’ Or in the form of a rhyme: ‘It gives me the creeps! Being the black sheep!’ Or simply, ‘I wish I was dead.’ Black humour that seems to be both a heartfelt desire and a grotesque exaggeration. She asks the girl who has brought her groceries whether she would like to see her daughter’s 2003 documentary The Holocaust Experience as a thank you. The girl responds with, ‘Yes, I would like that.’

Hoogendijk exploits the Kammerspiel form of her documentary to the maximum. The house is like a second skin, a body with a history, shaped by experiences and events. Its common thread is television shows of railway journeys. There are images that were shot when she is visiting her mother, sometimes in the company of her brothers. There are webcam images of the mother alone grumbling through her Amstelveen house until late in the night. As usual, Hoogendijk does not shy away from letting us see the rough edges of her working method: how she herself sometimes appears in the frame, what happens on the fringes, and how her mother wants to direct her.

Exterior shots of the house show a protective shell whose lattice-like slat also makes it look an awful lot like a prison. From the inside we see a view of a wall with a roof, above which two treetops are sticking out illuminated by the evening sun: Mother Lous thinks it’s a ‘beautiful’ sight! It’s merely a matter of accentuating the right details.

Lous wants to become invisible, finds it too strenuous to relate to other people

Lous makes no secret of the fact that she doesn’t really take to other people. Even her cat seems more like a roommate than a friend. Just like the boss, the beast is slightly chubby, stiff, and miserable, although – unlike her – he does venture into the open air. Whenever there is a knock at the door, Lous starts trembling: she wants to become invisible, finds it too strenuous to relate to other people. Yet it appears from her stories that go with old photographs that she once did venture outside, was married for four years, had three children, and has indeed known happy days. Now she says what really makes her happiest is being alone.

The “friends” and “dear acquaintances” that now surround her are a lot easier to handle in that respect. People from the TV have one big advantage: you can turn them off whenever you want, at the push of a button. You don’t have to try and fit in with them, you can just be yourself. A camp like Theresienstadt brings a constant state of panic down upon you, Lous says. ‘You become alienated, your feelings become switched off, you lose your own being: you are no longer who you used to be.’ It’s troublesome even when the cat demands something. Nothing is good, Lous grumbles as the beast meows for her help to open a door. ‘God save me.’

Housewitz is not just about being imprisoned but escaping as well. Imagination turns out to be an important counterbalance to the spectres of fear that visit Lous in her dreams. Besides the importance of having a safe haven, this film is also about home as a starting point for a journey through the world. If physical travel is not possible, TV images or music can lend a hand with fantasy travel. In these times of corona and lockdowns, the portrait consequently transcends her mother’s specific traumatic past and says something in a broader sense about what living in a solely inner world means. And so, the film is also an ode to human fantasy: about how images, letters, objects, or music can stir you, evoke thoughts, and comfort you. A song by DJ Tiësto turns out to have a surprisingly cathartic effect: the ethereal sounds stimulate Lous’ imagination. She sees something come out of it, it gets her charged up: ‘Energetic, like you’re in love, your head in the clouds,’ she says.

Lous: 'A camp like Theresienstadt brings a constant state of panic down upon you'

Just how much the documentary metaphorically portrays the house as a second skin is clear in the role played by the upstairs rooms. They are chaotic, a source of happy and unhappy memories, crammed with “unprocessed junk”. Memories are retrieved from them, excavated from the past, and tidied up with the help of the children. When one of her sons comes to help clear things out, he exclaims, ‘Man, what an incredible mess it is here!’ Lous herself puts it this way: ‘My entire life has been an accumulation of clutter.’

It is extraordinary to see how new memories are also made from reviewing the Westerbork camp letters, old photographs, and clothes she kept. Life between four walls is not all doom and gloom. And the past is not only a source of misery. Yes, Lous feels an ‘enormous aversion’ to looking at the old Westerbork letters. But she is delighted with some special garments that come out of the boxes: ‘A gem! A Schnuckel!’ A summer dress brings sunshine: ‘That was so nice!!!’ And then Lous suddenly turns out to have made real trips, as evidenced by a plaid she once brought from Lausanne.