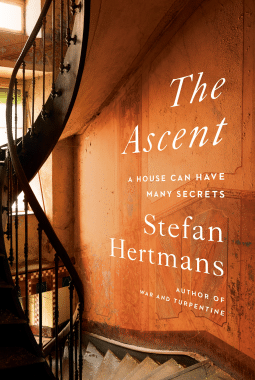

A Literary Triumph: ‘The Ascent’ by Stefan Hertmans

In his novel about a Flemish Nazi collaborator, bestselling author Stefan Hertmans, famous for War and Turpentine, reveals the ability to empathise with vastly differing characters. The Ascent presents a sharp image of life under German occupation, which Hertmans links perceptively to the personal history of his characters.

Stefan Hertmans

Stefan Hertmans© Saskia Vanderstichele

Stefan Hertmans’ latest novel, The Ascent, which has now also been published in English, is richly illustrated for a novel, featuring small photos, sometimes vague snapshots, portraits and group photos, scanned letters, official documents, buildings, furniture and items of all kinds that play a role in the book. The images are not generally expressive in themselves; the author perhaps wished to lay his cards on the table (to head off criticism of the kind directed at War and Turpentine): to anyone who may doubt the authenticity of my book, behold, here are my sources.

The book is more than a documentary novel, however. At countless points crucial to the author of a novel, those sources fall silent, leaving the writer to penetrate to the most dramatic dimensions of the history he has researched, drawing on his imagination.

Unspoken and hidden dimensions are inherent in the history of The Ascent, which centres on clandestine wartime activities, the associated shame, on betrayal and disloyalty in a political and moral sense and in love and family life, as well as the capacity to see one’s own mistakes or those of others.

Not for the first time, Hertmans demonstrates the ability to empathise with vastly differing characters, the precise opposite of the SS order he cites a couple of times, instructing officers to be unempathetic – a forced blinding which was to enable murder and subsequent “heroic” silence on the matter. In that sense, The Ascent may be called a literary triumph.

The starting point is a biographical fact. In the summer of 1979, Hertmans bought an old house in the district of Patershol in the historic centre of Ghent. In the process, the notary involved made a couple of apparently off-hand remarks about previous owners. “They were perfectly respectable people,” although on the mantelpiece there was a bust of “well, you know whom, Herr Dolf”. Apparently, the significance was lost on the buyer at the time.

More than twenty years later, he is handed a book titled Zoon van een “foute” Vlaming

(Son of a Flemish man on the wrong side) and realises that he has been living all that time in the house of a former SS officer. The name of the son, Adriaan Verhulst, will have further spurred him on to immerse himself in the life of that Flemish man deemed to have been on the wrong side, as Hertmans had been taught history by him at university.

That Flemish man, Adriaan’s father Willem Verhulst, is not just slightly on the wrong side, he is unambiguously and extensively wrong, as revealed by Hertmans’ research. The first event of interest in young Willem’s life – possibly a partial explanation for his later slipping into criminality – takes place when he is four: during an event at his elder sister’s “dance studio”, he suddenly falls to the ground, convulsing and foaming at the mouth; when he comes to, he can no longer see anything. One eye later recovers, the other remaining blind. Although it bothers him a great deal and he is also sometimes bullied for it, by his own account he has a happy childhood until the age of thirteen, when his mother dies.

After that, however, things rapidly go downhill. At the age of nineteen, under the influence of the Flemish nationalist politician August Borms, and after being rejected for military service due to his eye, in 1917 he becomes a radical supporter of the Flemish Movement. He hates anything French and makes no effort to conceal his aversion to the Belgian state or his “Greater German sympathies” and after the German surrender, he flees to the Netherlands for a while.

Hertmans succeeds masterfully in retaining the reader’s attention, thanks to his ingenious arrangement of the many revelations about Willem’s life

It therefore cannot come as much of a surprise that in 1940, when Ghent is groaning under the German occupation, he is appointed director of the “Gentse Radiodistributie”, a propaganda radio broadcaster in the purest form. Willem’s career in broad strokes follows the history of the war, making it largely predictable, which must undoubtedly be a handicap to the chronicler; nevertheless, Hertmans succeeds masterfully in retaining the reader’s attention, thanks to his ingenious arrangement of the many – often shocking – revelations about Willem’s life.

Those discoveries leave a trail of destruction through the lives of his nearest and dearest. Willem is married to a Dutch woman from a strict Reformed background, Mien, from whom he long keeps his dark practices secret. She wants nothing to do with bombastic militarism: “All those uniforms made her skin crawl.” Meanwhile, without a trace of compassion, Willem assiduously keeps lists of all foreign, anti-Germanic elements, and is thus responsible for the brutal murders of countless citizens. Hertmans is at his strongest when he describes the sultry, unspoken tension between Mien and Willem, and later also between Willem and his children.

His novel not only presents a sharp image of everyday life under German occupation, particularly the collaboration and resistance in Ghent, but it also links it perceptively with the personal histories of his characters.

In September 1944, Willem is one of 15,000 Flemish collaborators to flee to Germany – along with Griet, his lover of many years and ideological soul mate. There is no question of regret, at most self-pity. During one of the RAF bombardments his temporary accommodation in Hannover is hit, yet “Griet’s stories of the event verge on the idyllic.” Not a word about the horrors of war: “Titi and Wim munched porcini with gusto in an Arcadian setting. … Her account reads like postcards from a happy holiday.”

Nazi collaborator Willem shows no regret, at most self-pity

At the end of 1945 Willem is arrested. In 1946 he is transferred to a prison in Flanders. A “highly incriminating document” in his handwriting is read out to the court, in which he argues for the “radical extermination of all centres of degeneracy and bastardisation in Flanders”. In 1947 he is given the death penalty, which is converted to life imprisonment, but in 1953 he is set free. There is still no suggestion of regret. His “prison letters” lamenting his plight – analysed mercilessly and in minute detail by Hertmans – reach unprecedented levels of obscenity.

For a moment I thought that the story was finished and that Hertmans might have done better to end his book on this point, around three quarters of the way through. But I was compelled to change my view. The follow-up soon turned out to be more than an obligatory epilogue. The author himself comes into view, including his role as a student demonstrating in 1968. He sketches nuanced portraits of Willem’s children: his two daughters, of whom one, Letta, as a counterpart to Adriaan’s book about the father on the “wrong” side, wrote a tribute to Mien, their so humiliated, but always decent mother; and of course there is a portrait of Adriaan, the pride of the family, who succeeded in becoming a professor and was “a feared and a respected opponent in all public debates about culture or equal rights for the Flemish”, but who had been ironically and quite unjustly characterised by an always jovial Godfried Bomans as “having a ‘Burgundian’ outlook and belonging in a painting by Bruegel”.

Coincidence also affords the author a variety of surprises which could not have been permitted to go unremarked. For instance he is given a booklet which was published in 1997 by the extreme right-wing Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) on the occasion of the ninetieth birthday of Willem’s disreputable lover Griet, who lived a life consumed by resentment. Her eulogy, untainted by any hint of regret or guilt, turns out to have been written by Bart De Wever (current chair of the Flemish nationalist party Nieuw-Vlaamse Alliantie and mayor of Antwerp, editor).

Also noteworthy is Hertmans’ discovery that the bust of “Herr Dolf”, an important motif in the book, turns out to have been made by the father of a good friend. The war, as he so poignantly demonstrates, casts a long shadow in the lives of countless survivors.

Excerpt from 'The Ascent', translated by David McKay

Can you see the animal running, always in the same way?

Alessandro Baricco, The Barbarians, trans. Stephen Sartarelli

It was in the first year of the new millennium that a book came into my hands from which I learned that for twenty years I had lived in the house of a former SS man. Not that I hadn’t received any signals; even the estate agent, the day I visited the house with him, had mentioned the previous occupants in passing, but at the time my thoughts were elsewhere. And maybe I repressed the knowledge, saturated as I had been for years with the painful poems of Paul Celan, the testimonies of Primo Levi, the countless books and documentaries that leave you speechless, the inability of a whole generation to describe the unthinkable. Now I saw my intimate memories invaded by a reality I could scarcely imagine but could push away no longer. It was as if phantoms came looming up in the rooms I’d known so well; I had questions to ask them, but they walked straight through me. There was nothing I was so loath to do as write about the kind of person who now began wandering the corridors of my life like a ghost.

I could still see the day I had noticed the house for the first time. It must have been in the late summer of 1979. I was walking through a dusty city park bordered by a row of old houses; through the gaps between the fence posts I glimpsed the back gardens. Winding through the rusty rails of one of these fences were the thick, near-black branches of a wisteria. A few late clusters of flowers hung low, sprinkled with dust, but their fragrance touched a deep place, taking me back to the overgrown garden of my childhood; curious, I stopped for a better look through the fence. What I saw was a small, neglected urban garden where a slender maple shot up among nondescript clutter; a coal shed with leftover firewood under a layer of black dust; some five metres further away, the broken window of the run-down annex; and next to that a veranda with a high arched window offering a view of the interior, all the way to the other side. I stares straight through the dark, empty rooms. The front windows gleamed with vague light from afar.

A strange excitement ran through me; I walked out of the park and made a U-turn into a small, dark street in an old part of town. There I found it: a large townhouse with a pockmarked front, into which moisture had eaten its way over the years. With its high windows and flaking front door, the building had known better days; it was obvious it had been vacant for some years. In one of the windows hung a sign, FOR SALE, wrinkled from the damp. It began to drizzle as it can only drizzle in old cities; the copper flap of the letterbox gave a brief, gloomy rattle in a gust of wind.

The district is called Patershol, named after the narrow canal that gave access to the monastery in the Middle Ages, through which the paters, the monks, would bring in stocks of food and, as the story goes, smuggle whores inside. The area once belonged to the Counts of Flanders; this historic part of the city is next to a twelfth-century fortress and was for centuries the home of the city’s leading dynasties and the haute bourgoisie. With the rise of the proletariat in the nineteenth century, many stately buildings were replaced with working-class housing. Poverty set in, and over the years the district developed a bad reputation. The narrow alleyways and cul-de-sacs fell into decay until the student revolt of the late 1960s, when bohemian artists settled there. The house I was looking at was on the northeastern edge of the district in a side street called Drongenhof, not far from where the Leie River flows past the musty old houses, slow and dark.

Want to read a longer translation? Take a look at Flanders Literature.