A Monument Against Fake News: The Planetarium of Eise Eisinga

The oldest working planetarium in the world can be found in Franeker in the Dutch province of Friesland: the Royal Eise Eisinga Planetarium. The Netherlands wants this unique planetarium to be included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. The life’s work of Eisinga (1744–1828) is a monument of the Enlightenment; He wanted to use science to stop the madness of his time. What about today, in times of “virus madness”, fake news, and vaccine doubt? Albert Meijer, who grew up in Franeker, explores Eisinga’s legacy.

If you look at the Enlightenment in the Canon of the Netherlands, you will see a strange blue circle. It is the ceiling of the planetarium, created by the wool comber Eise Eisinga from Franeker, the Frisian town where I grew up.

Portrait of Eise Eisinga by Willem Bartel van der Kool, 1827

Portrait of Eise Eisinga by Willem Bartel van der Kool, 1827© Wikimedia Commons

Franeker, or Frjentsjer in Frisian, counts less than thirteen thousand souls, but those souls are all proud of a few achievements in which they delight many visitors:

1. It is one of the Frisian eleven cities, containing a beautiful old town centre;

2. In the inner city lies the Sjûkelân, a holy patch of grass for the Frisians. the oldest existing sporting event in the Netherlands, the largest annual handball tournament (“PC”), is held here;

3. It is home to the oldest working planetarium in the world: the planetarium of Eise Eisinga.

As a child, I thought the world was largely populated by the mentally ill. Our house was next to an apartment complex that housed people when they were discharged from a psychiatric hospital, generally only for a short time. I remember the woman who stopped at every flower she came across to smell it, and moved like a bee from pistil to pistil through the street; the man who, in a psychotic fit, threw all his furniture out of the window, buck naked; the man who, every week, lined up alongside the barrel organ with a fly swatter pretending to be a conductor, and gave every woman who walked by a slap on the ass. My world was small, and yet cluttered.

The Eise Eisingastraat in Franeker, with the Planetarium on the right

The Eise Eisingastraat in Franeker, with the Planetarium on the right© Wutsje / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0

The end of times

Such madness was also an important part of life in the city and surrounding villages during the time of the University of Franker (1585–1811). When the sun rose on 8 May 1774, and let its light shine on the nearby village of Bozum, Eelko Alto, the local pastor, must have had a sleepless night. According to him, the Apocalypse was near, because that day the planets (Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Mercury) would collide with the moon. The earth would be catapulted straight into the sun by the explosion.

About twenty kilometres away, the young wool comber Eise Eisinga was smiling. He had read the ideas of Reverend Alta in the reverend’s book, but as an amateur astronomer Eise knew it was nonsense; the planets were not on a collision course, and the earth would not end that day. In fact, Eisinga wanted to fiercely fight the pastor’s madness and began building a planetarium, a planetary system made to scale, moving in real-time by means of a complicated clock mechanism. Eisinga built his planetarium in the only place available to him: the timber roof of his home in Franeker.

The planetarium in Eisinga’s living room

The planetarium in Eisinga’s living room© bertknot / Wikimedia Commons

Two and a half centuries later, Eisinga’s planets are still moving across the bright blue painted woodwork above the stone floor, forever making their rounds between fireplace and bedstead. The lead of the pendulum clock that drives the whole thing has to be replaced every once in a while, but the wheels keep on ticking steadily. In all those years, the painted spheres – which are supposed to represent Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn – are only a few seconds ahead of their much larger counterparts in the sky. When Eisinga finished, in 1781 after seven years of diligent work, Uranus was discovered, but there was no more room in the little home of the wool comber. The discovery of Neptune was then another sixty years away; dwarf planet Pluto was not discovered until 1930.

A monument against fake news

While the earth moves a tiny bit on Eisinga’s ceiling, the curfew goes into effect outside. The streets are whisper quiet (although that is often the case in Franeker, even before the COVID-19 pandemic). A few individuals walk their dogs on the strongholds surrounding the city. Very occasionally, someone with a vital profession drives by. I also walk the dog and pass the Planetarium, with its large sundial, which shows no time at this hour.

In accordance with the spirit of the Enlightenment, Eisinga built a monument for science, which also served as an indictment of superstition

In accordance with the spirit of the Enlightenment, Eisinga built a monument for science, which also served as an indictment of superstition, of assertions that were based on nothing: the gut feeling of mad pastors who sold their delusions as truth. The Planetarium is a symbol of the victory of reason over madness, a perpetuum mobile (a device that exhibits perceptual motion) against what we would now call fake news.

But as the world kept on turning the superstition remained, and even seemed to grow stronger. The news reported more and more aggressive ‘drinking a cup of coffee together’ demonstrations at Museumplein. In Eindhoven, a woman was sprayed down by a water cannon. In the United States, a gunman wanted to enter the imaginary basement of a pizzeria.

In Franeker, things remained quiet, at least in the public space. I began to wonder if there was a causal connection between Eise Eisinga’s science monument and the apparent lack of Corona madness. I decided to investigate the place where I expected to find the most conspiracy theories: Facebook.

I began to wonder if there was a causal connection between Eise Eisinga’s science monument and the apparent lack of Corona madness in Franeker

I looked at the comment sections of the local newspaper (the Franeker Courant) and the online newspaper (FranekerActueel). Apart from a few critical posts about governmental policies and vaccinations, I couldn’t find any real untruths here, so I decided to infiltrate a private Facebook group: Friends of Frentsjer. But before I could properly and surreptitiously check the posts for fake news, I was welcomed by name as the 4,700th member of the group, apparently a noteworthy addition. I felt guilty that I had joined the group only to look for fake news, a feeling that was reinforced when I found very few conspiracy theories among the thousands of posts and comments. I saw photos of winter walks across the city’s strongholds, old black and white postcards, messages of people trying to track down former neighbours who they lost sight of ‘Greetje died a long time ago,’ as someone wrote in a comment.

Only after a photo was posted of the local gymnasium being converted into a vaccination centre, someone commented saying that toxins were being injected here. But he appeared to be a loner; other group members responded impetuously, and asked the man critical questions about what his opinion was based on.

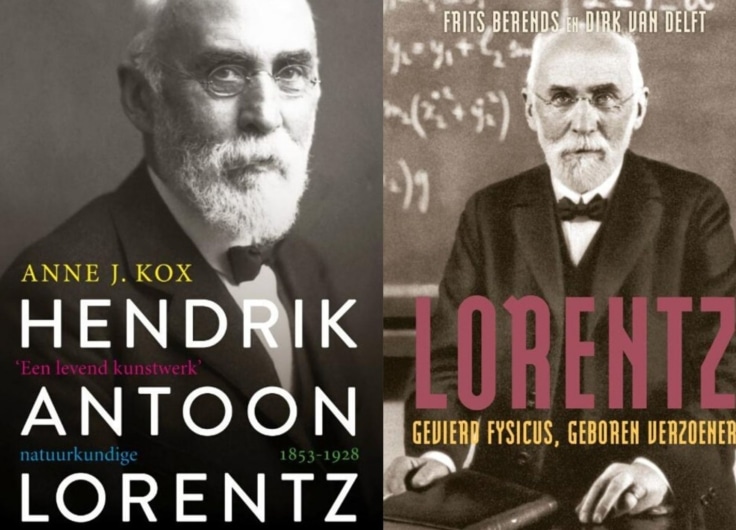

Oort cloud

At the Breedeplaats, Franeker’s church square, there is a fountain by French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel, which emits a cloud of steam when you press a button. The fountain is a depiction of the Oort Cloud, which was given to the city as part of Leeuwarden-Fryslân 2018, when Leeuwarden was allowed to call itself the European Capital of Culture.

The Oort Cloud Fountain by Jean-Michel Othoniel, near the Martini church

The Oort Cloud Fountain by Jean-Michel Othoniel, near the Martini church© RomkeHoekstra / Wikimedia Commons

The Oort cloud is not actually a cloud, but a thick layer of billions of comets swarming around our solar system. The cloud was discovered by Jan Hendrik Oort, an astronomer born in Franeker in 1900.

If you were to extend the scale of Eisinga’s planetarium, my former elementary school would float somewhere in this Oort cloud. The school was right behind the planetarium – every day I walked down the street that has been called the Eise Eisingastraat for years. Yet we never went inside. We saw the planetarium on Omrop Fryslân, but never paid a visit. Maybe it was because the teachers, with 37 children in their class, didn’t have the energy to organize trips in addition to taking care of so many children. I only learned that Franeker had produced a rock star among astronomers, in addition to Eise Eisinga, with the arrival of the Ort Cloud Fountain.

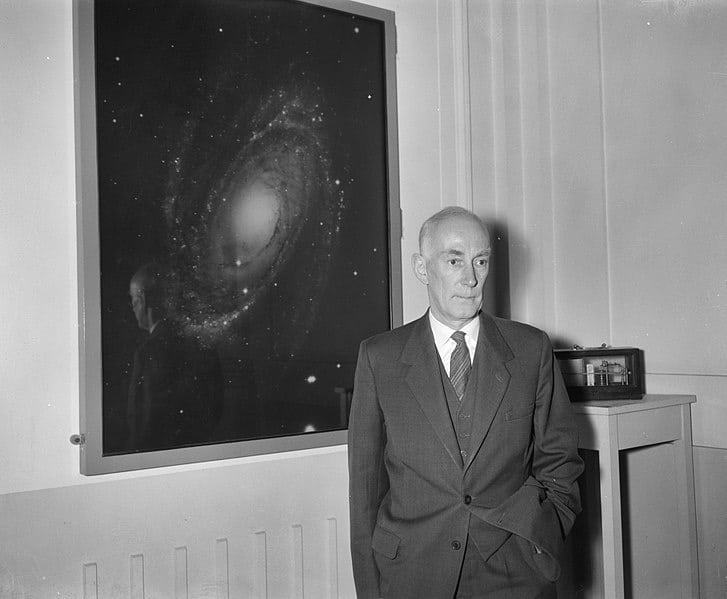

Jan Hendrik Oort, professor of astronomy at the Leiden Observatory, May 1961

Jan Hendrik Oort, professor of astronomy at the Leiden Observatory, May 1961© Joop van Bilsen / National Archives, Anefo collection

In the meantime, I was starting to hear the first stories from around Franeker, which suggested there were indeed more conspiracy theorists running around here than I initially thought. My sister, who is a nurse in a nearby town, has some colleagues who don’t want to get vaccinated because of alleged microchips in the vaccines; an acquaintance refuses to get vaccinated even though she works in close contact with vulnerable target groups; and a family member is increasingly speaking out on social media against the “virus madness”.

Unesco

So, the life’s work of Eisinga that tries to fight madness with science has not gotten through to all of the people of Franeker. Perhaps an annual class trip to the planetarium would not have made the difference either; people seem to like to shape their own reality.

Nevertheless, the importance of the planetarium is increasingly emphasized. In 2022, the building will even be officially nominated by the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science for consideration for the Unesco World Heritage List. Whether it makes a difference or not, one thing is certain: no matter how they relate to science, the people of Franeker will be boasting about Eise Eisinga’s astonishing structure for centuries to come.