A Soldier at a Typewriter. Alfred Birney’s Novel about Java

The Interpreter from Java by Alfred Birney is a throat-grabbing father-son novel about the colonial past in the Dutch East Indies, which highlights the lasting consequences of a civil war in a penetrating way. ‘Birney’s most important book is more than a contemporary Max Havelaar or a Dutch version of Malaparte’s Kaputt.’

Alfred Birney

Alfred Birney© Patricia Bo

Alfred Birney’s (b. 1951) book De tolk van Java (The Interpreter from Java) makes its readers shiver. It is a novel about a traumatised father, Arend, who murdered dozens of people in Indonesia during the war, a war which for him simply continued within the family he subsequently began in the Netherlands. That war only ends for Arend’s son, the first-person narrator of the novel, with his father’s death. ‘I won’t fight anymore, this is where it ends’, states the final sentence of this rich novel about identity, trauma, racism (in Indonesia, in the Netherlands and in the Dutch army), the Japanese occupation of Indonesia, the bloody battle of the Dutch against Indonesian independence, a father who abuses his children and the boarding-school life which begins for the narrator and the four other children from the family when they are sent away from home. The reader will find no sweet nostalgia here (that is a ‘lie’, writes the father, and the narrator wants nothing to do with it either) or a description of childhood paradise, as is often the case in famous Dutch literature about Indonesia.

Birney has lived with this theme for years, but his novel came along at the right moment: in 2016, the year in which De tolk van Java was published, the Netherlands saw the reopening and deepening of a discussion of war crimes committed by the Dutch army, which was tasked with restoring the colonial administration in Indonesia after 1945, and about the government which did not wish to accept independence. Until then the official version had stated that the main issue had been incidental ‘excesses’ (rape, robbery and plundering), rather than structural war crimes, covered up by the colonial administration, the Dutch government and the military judiciary. After new research it can no longer be denied that the Dutch army was responsible for systematic war crimes.

The Interpreter from Java begins with a sentence about Arend which stretches over more than a page, describing what he saw and heard, stating who he betrayed, and that he was tortured and helped the Allies. These are stories which Arend always told his son, his son who hates him, who sees him as a mass murderer and who accuses him of largely ruining his life. Arend raises his children as he himself was raised: harshly and with liberal use of his fists, confirmed in his path by his traumatic war experiences. He always sleeps with a knife within reach, even taking it with him in his bicycle pannier when he goes into town, and one day he pursues one of his suspected enemies in The Hague carrying it.

Birney makes his father the central character and his identity is far from unambiguous: born in Java as the illegitimate son of an Indo-European father, who refuses to acknowledge him, and a Chinese mother, he is the only one in his family to identify with the Netherlands. While his fellow soldiers keep pin-ups on their walls, above his bed hangs a portrait of the queen of the Netherlands. Due to the turbulent events in Indonesia, Arend regularly changes sides and doubts his choices: together with Indonesian friends he fights the Japanese occupiers, but after 1945 he sides with the Dutch against his compatriots. Indonesia is not his country, he says: as an illegitimate child he has been humiliated by the ‘Indo’ (Dutch-Indonesian) people and as an Indo boy he found himself caught between the Dutch and the Indonesians. His son doubts his principles and suspects that Arend simply always took the side of the strongest party. Just before his departure for the Netherlands, Arend plans to change his name to Noland, in order ‘to distance himself from colonially tinted Indo-Europeans and similarly white Indonesian Dutch people’. It is a name which speaks volumes for his hybrid identity, and one which also has predictive power, as he will never feel at home in the Netherlands either. His intended paradise turns out to be a country riddled with racism.

When I say that Birney’s novel makes me shiver, it is an allusion to a pronouncement by a member of the Dutch House of Representatives, who in 1860 after the publication of Multatuli’s then controversial novel Max Havelaar said that ‘recently, a certain chill has gone through this country, caused by a book’. Birney makes various references to this classic of Dutch literature: in his mother’s new friend’s pantry the narrator finds ‘the sea chest from my father’s passage to the Netherlands’. He continues: ‘I opened the chest and saw all sorts of paperwork inside: books, piles of papers, letters, photos and files.’ This is reminiscent of another package, which also came from Indonesia, ‘Scarfman’s package’ from Max Havelaar. Droogstoppel, one of the narrators from that book, says, ‘There I found treatises and essays’, followed by a list of subjects. While large parts of the ‘Package’ are woven into Max Havelaar, parts of the father’s manuscript are published in The Interpreter from Java.

In his manuscript, which he tried in vain to publish, Arend describes his youth and the period up until his forced departure to the Netherlands. Forced, because he was blacklisted by Sukarno, the first president of the independent republic of Indonesia, a country in which he was now unsafe because he had murdered countless Indonesian freedom fighters. This message is central to the novel and the narrator confronts his mother, who has very little interest in Indonesia, and his brother with its content, raises questions and provides commentary. One part, almost 200 pages, in which Arend recounts the events from 17 August 1945, the day on which Sukarno announced independence, until he leaves Indonesia on a ship bound for the Netherlands, is included without interruption or commentary from the narrator. It consists of sometimes detailed descriptions of horrific crimes – on the side of the Indonesian freedom fighters too. For that reason, and because it is written from the perspective of the Dutch army, the losers, it can be compared with the atrocities in Curzio Malaparte’s 1944 novel Kaputt. Malaparte, too, opted for the perspective of the losing party.

Those responsible for the Dutch war crimes in Indonesia have never been prosecuted and the Dutch government will have to adopt a new position with respect to that period. While historical research leaves no room for doubt, Birney presents a more complicated and less straightforward take on the entire issue – that is the task of literature. Questions of whether Arend wrote the truth and whether his memories are correct pervade throughout the book and in the discussion between the brothers. Here, too, Multatuli offers a clue, as the question is not whether all the details are true, but what effect the book has on readers. After the story of Saïjah and Adinda in Max Havelaar, Multatuli writes, ‘But I know more. I know, and I can prove, that there were many Adindas and many Saïjahs, and that what is fiction in particular is truth in general.’

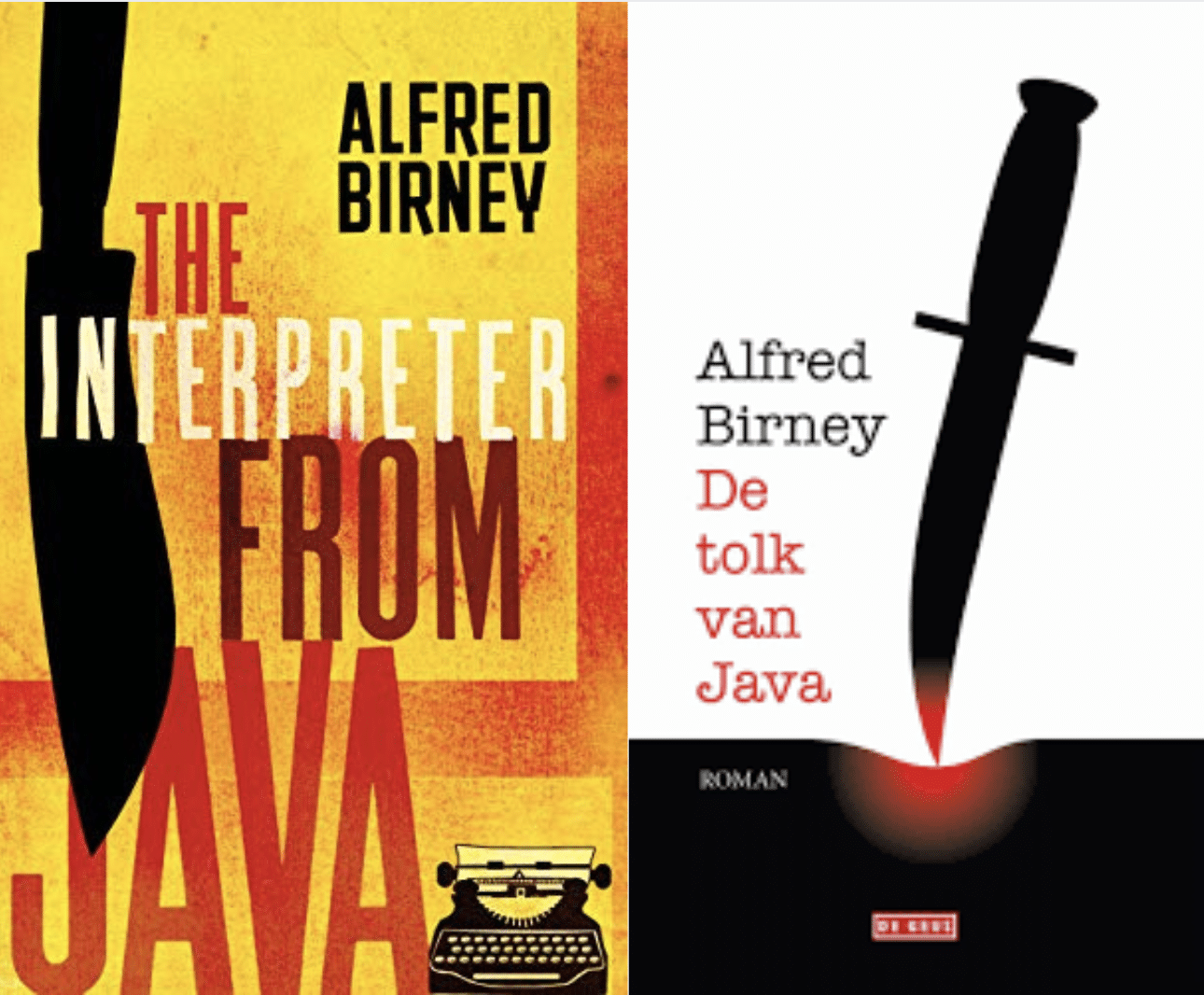

But The Interpreter from Java is more than a contemporary Max Havelaar or a Dutch version of Malaparte’s Kaputt. Birney has now published fifteen novels, essays and anthologies and this may well be his most important book, in which he impressively unites all the themes of his previous work. It is only fair that he has won two Dutch literary prizes for it.

Alfred Birney, The Interpreter from Java, Head of Zeus, London, 2020

Original title: De tolk van Java, De Geus, Breda, 2016

This article was previously published in the 2018 yearbook The Low Countries № 26.