A Triple First and More: the New English Translation of Multatuli’s Max Havelaar

Max Havelaar, the classic novel by Multatuli about Dutch colonialism in Java, has a brand new English translation. Reinier Salverda, Honorary Professor of Dutch Language and Literature at University College London, reread what is perhaps the greatest Dutch novel of all and noticed many improvements. “The new translation is as fresh as if Multatuli had just written it himself.”

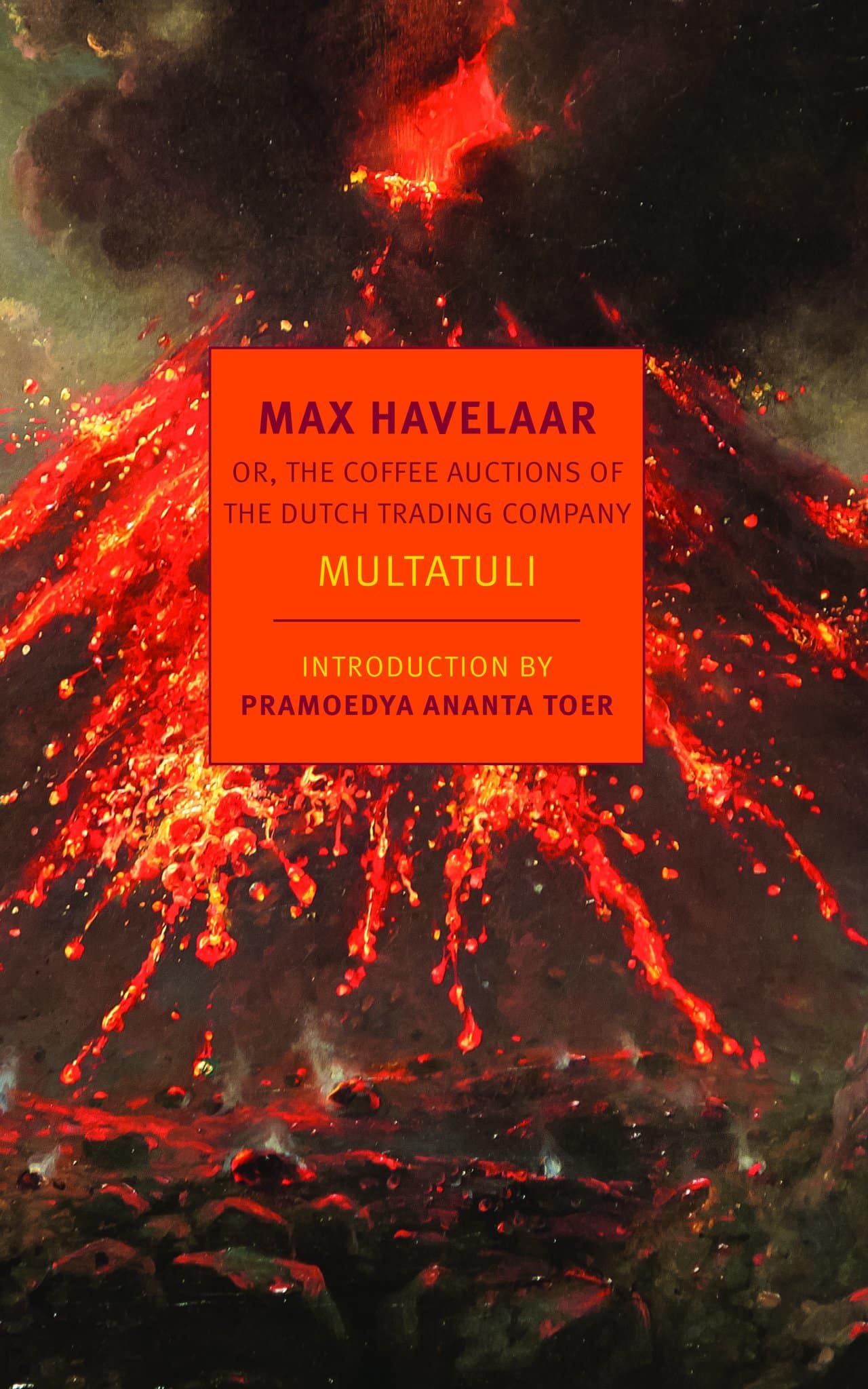

New English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019

New English edition of Max Havelaar, 2019On Wednesday 13 March 2019 the weekly Dutch Translation Seminar at the University College London was dedicated to Multatuli’s great novel of 1860 on the Dutch colonial era: Max Havelaar or, the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company. The book wasn’t out yet in the UK, yet – thanks to its publisher, the New York Review of Books, and to Waterstone’s Gower Street Bookshop – we received the necessary advance copies in time before the Seminar, and well before the bulk of the books is due to arrive, Brexit permitting, in the UK in April-May.

Secondly, in addition to the books, and thanks to the London Book Fair, we also had one of the novel’s translators, David Mackay, and some others, notably Mikael Johanis from Indonesia.

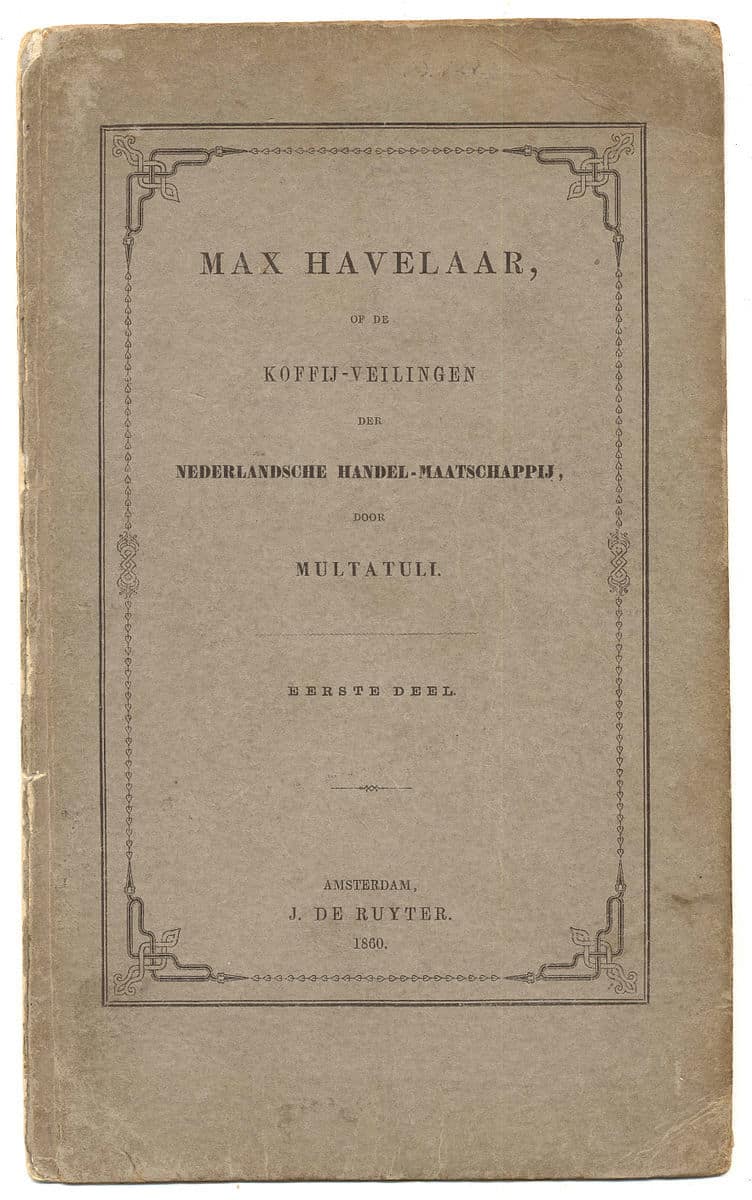

Thirdly, this week it is kick-off time for our strategic lobbying and fundraising campaign for the future of Dutch and Low Countries Studies, both at UCL and throughout the UK, in tandem with a celebration of the centenary achievements since 1919 of the UCL Chair in Dutch. It is fitting to start this with Multatuli’s Max Havelaar, first published in the Netherlands in 1860, first published in English translation in 1868, and by any standard today still the greatest work ever in Dutch literature.

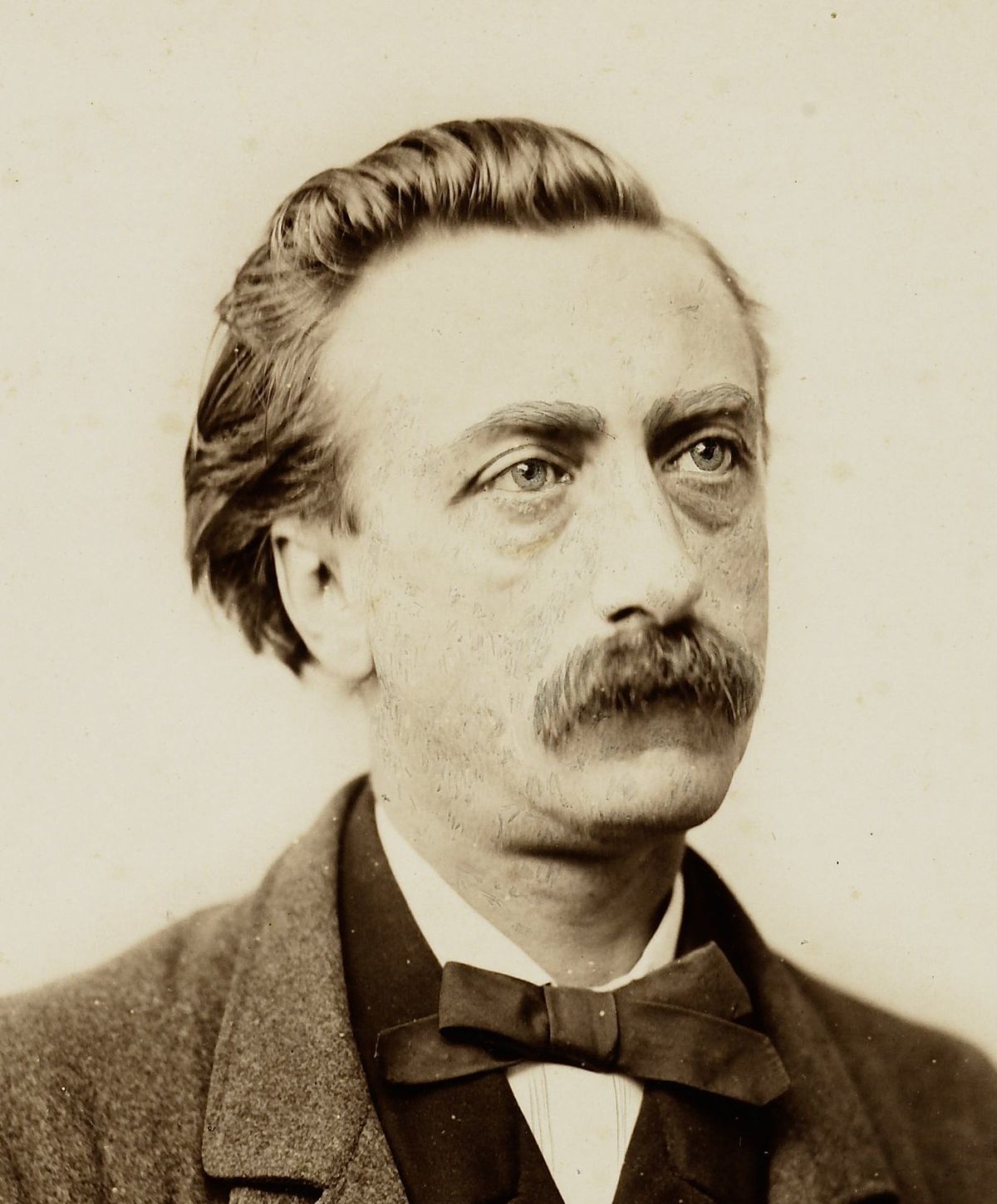

Multatuli (1820-1887)

Multatuli (1820-1887)Chaired by UCL Prof Reinier Salverda, the initial focus of our seminar was on the innovations offered by the new translation: a more colloquial and accessible English style throughout, and a stronger handling of the novel’s Dickensian humour – Multatuli’s seductive but also deeply critical play on the two national archetypes, both much larger than the book in which they figure: the Amsterdam coffee broker Drystubble, cantankerous champion of truth and common sense who makes his money off the Dutch monopoly on auctions of Javanese coffee, versus the idealistic colonial civil servant Max Havelaar, who believes in humanity and justice, and when he is sent to the District of Lebak, happens to takes his oath to protect the native Javanese rather more literally than was customary – a figure of inspiration to the Dutch Fair Trade Movement, of which he is the patron saint today.

Another theme in our discussions was how this new translation compares to the previous one, by Roy Edwards of 1968, still available in Penguin Classics. Here we took a number of soundings throughout the text, employing close reading as a technique of postcolonial criticism – first the opening page, where Drystubble makes his unforgettable entry – then Multatuli’s discussion of linguistic prejudice and discrimination in colonial society on account of their way of speaking against people who weren’t born and bred Dutchmen – thirdly, the famous and widely translated tale of Saijah and Adinda, two Javanese villagers, young, romantic and in love, who came to a very bad end at the hands of the Dutch colonial army – and finally, the magnificent political peroration by Multatuli himself, who – almost like a Javanese puppeteer – breaks through all the fictions and myths in his novel and launches into a fierce attack on the robber state on the North Sea that is Holland – with an appeal to the Dutch King, to put an end to the corruption and violence perpetrated in His name against his millions of native subjects in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).

Cover of the first edition of Max Havelaar, J. De Ruyter, 1860, Amsterdam

Cover of the first edition of Max Havelaar, J. De Ruyter, 1860, AmsterdamThe new translation is as fresh as if Multatuli had just written it himself. There are great innovations here: the addition of a new introduction by Indonesia’s greatest author, the much-persecuted Pramoedya Ananta Toer – the cover image of an exploding volcano on Java, by the famous Javanese painter, Raden Saleh, a contemporary of Multatuli – also, the use of recent Multatuli scholarship in particular the critical edition by Kets-Vree in 1992 – the inclusion of Multatuli’s own disillusioned notes which he added later in life – a Glossary of Indonesian terms, and a very helpful timeline. All these greatly enrich the book and enable readers of today to better understand this great novel, which – as Pramoedya said – ‘was the book that killed colonialism’.