A Wedding of Words. Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes Revisited by Connie Palmen

The relationship between Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath is one of the most famous love stories of Western literature. It ended in 1963 with the American writer’s suicide. Since then hundreds of publications about the poet couple have been published, featuring Plath as a martyr and assigning Hughes the role of traitor. In her masterful novel Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story) Dutch author Connie Palmen gives Ted Hughes a voice. She achieves this feat in bravura fashion.

When I heard that Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story), the most recent novel by the Dutch writer Connie Palmen (b. 1955), which was awarded the prestigious Libris Literature Prize in 2016, was about the relationship between Ted Hughes (1930- 1998) and Sylvia Plath (1932-1963), my first reaction was fairly negative. Hadn’t enough been written on the subject? There is the autobiographical work of Plath herself: a sizeable collection of letters, diaries, the roman-à-clef The Bell Jar and of course the poems, most of which have a decidedly autobiographical character. In the 1980s one biography after another appeared and in addition an unstoppable flood of memoirs and recollections by friends and acquaintances who had known the American poet in a particular period of her short life.

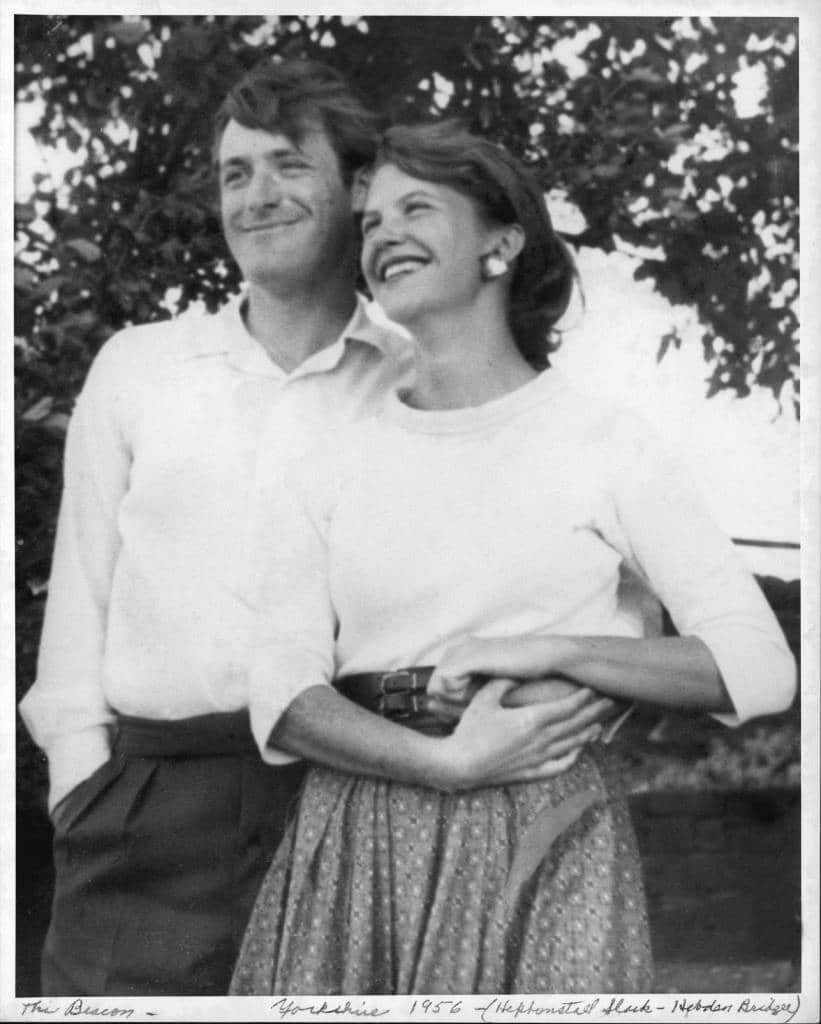

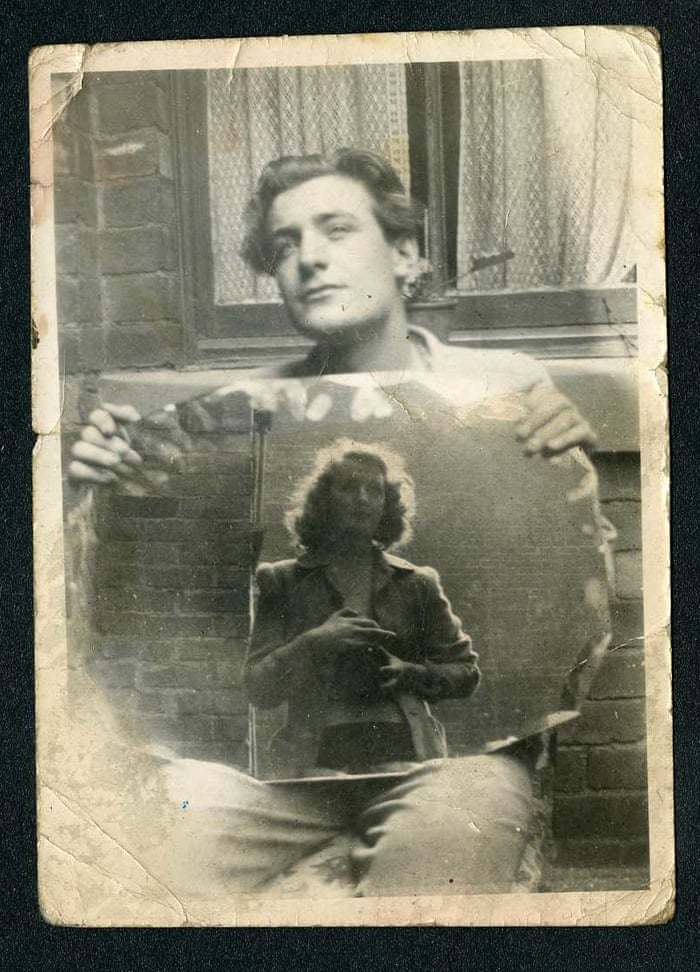

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath in Yorkshire, 1956

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath in Yorkshire, 1956© Photograph: Harry Ogden/Courtesy Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Massachusetts

Moreover ad hoc subgenres emerged around Plath and Hughes: examples include Her Husband: Hughes and Plath – A Marriage by Diane Middlebrook, on the two poets’ married life (1956-1963), and in 2013 – Mad Girl’s Love Song: Sylvia Plath and Life before Ted by Andrew Wilson, which describes Sylvia’s life up to her meeting with Ted on 25 February 1956. In the latter book we find an unbelievably exact record of every boy she ever dated, with whom she corresponded and who were her boyfriends, first in high school and later at Smith College.

The most curious book in this category is The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes

by Janet Malcolm. Malcolm interviewed a series of authors who had written about Plath and Hughes. In order to obtain permission for longer quotations those writers had to submit their manuscripts to the estate of Sylvia Plath, who committed suicide on 11 February 1963. At that point she had been living apart from Hughes for six months. Because they were not yet divorced and no will was found on her death, Hughes became her legal heir. For negotiations on copyright issues relating to her work he appointed his sister Olwyn, two years his senior, as a literary agent. In Malcolm’s fascinating book Olwyn Hughes is the central character.

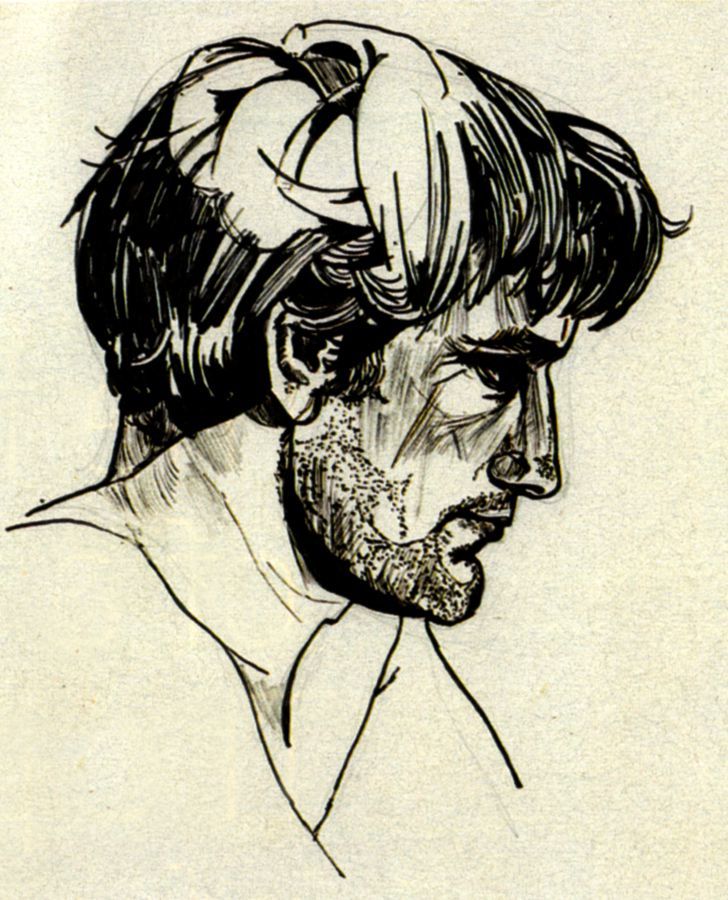

Ted drawn by Sylvia, 1956

Ted drawn by Sylvia, 1956Olwyn Hughes (who died on 3 January 2016) was an unrelenting gatekeeper. After Sylvia Plath’s death there was gossip suggesting that Ted Hughes was partly responsible for his wife’s suicide. He had supposedly neglected her after leaving her and their two children. Or rather, after he had been thrown out of the house by her because of his adultery. At the time they were living in rural Devon. In the winter of 1962/63 she had moved back to London, where she ended her life in dramatic circumstances. She put out milk and sandwiches for the two children, who were sleeping on the top floor, sealed the gaps in the bottom of the door with towels, opened the window and then went into the kitchen, where she put her head in the gas oven.

At that time Ted Hughes had published two volumes of poetry, both awarded major literary prizes. Sylvia Plath was the author of the poetry collection The Colossus and the autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, which appeared under a pseudonym. And then came this bombshell: the rumour mill was unstoppable, but Olwyn Hughes had other ideas. Anyone wishing to quote from Plath’s work at length had to work via her. And permission depended on the attitude of the author in the Plath-Hughes controversy. Those who did not clearly take Hughes’s side had her to deal with. In Janet Malcolm’s book you can read the evidence of how she tried to influence authors and pressured them.

Ted Hughes kept in the background as far as possible, especially after 1969, when his then girlfriend Assia Wevill gassed herself together with their young daughter. This could no longer be coincidence. In this the ‘libbers’ – as Ted and Olwyn Hughes called the feminists – found new ammunition for their attacks on the poet. In the background he may have been, but he was not idle. Little by little the work of Sylvia Plath was published. Hughes edited or collaborated on those posthumous editions – and intervened. He rearranged the poems in her best-known collection Ariel, and omitted a few. Passages in the letters and diaries were censored. Moreover, he admitted that he had destroyed the diary of the last few months of her life and that a second diary had vanished without trace.

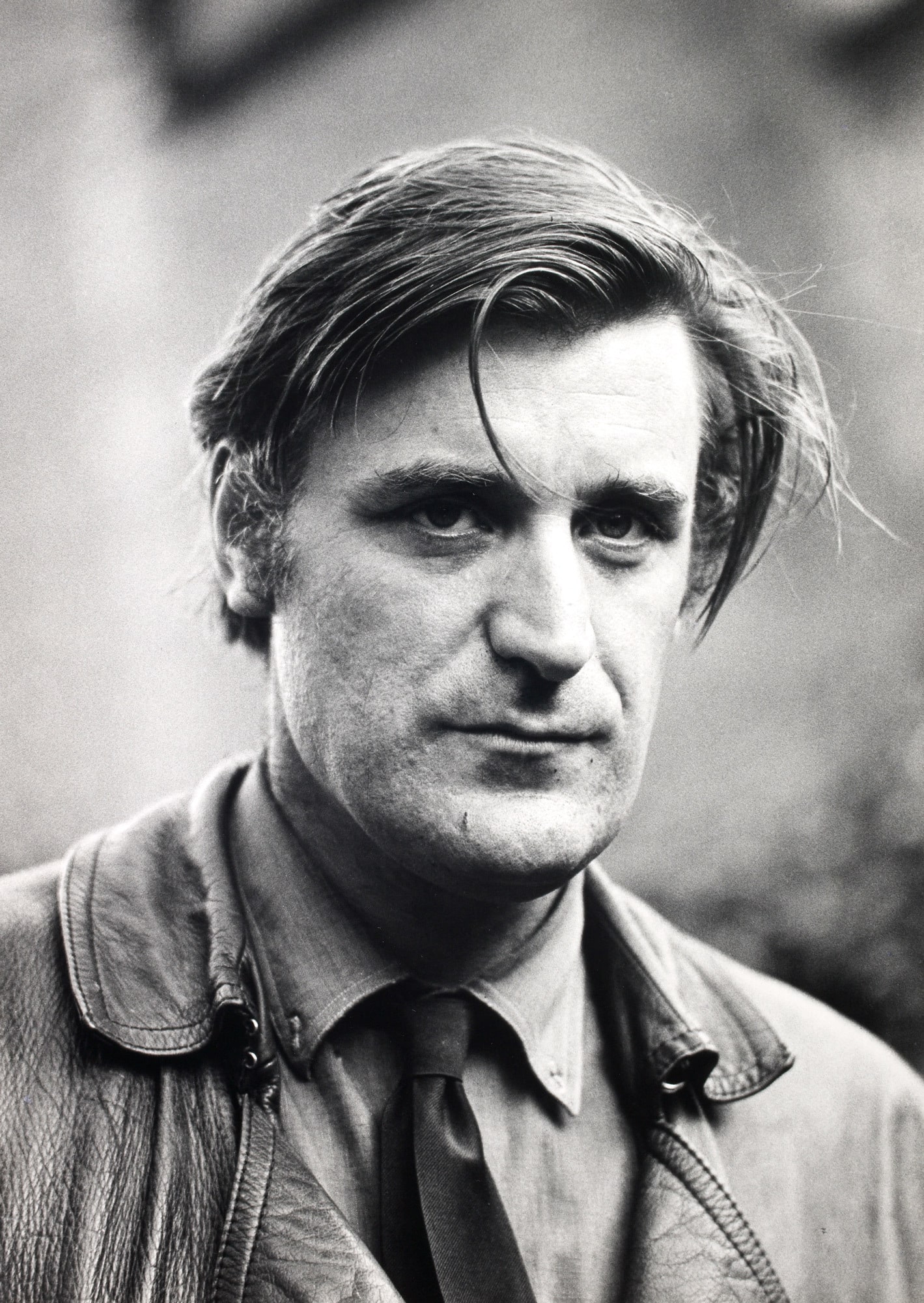

Ted Hughes

Ted Hughes© British Library Board, photo: Fay Godwin

Janet Malcolm quotes from a letter that Hughes wrote to Plath’s biographer Anne Stevenson: ‘I have never attempted to give my account of Sylvia, because I saw quite clearly from the first day that I am the only person in this business who cannot be believed by all who need to find me guilty.’ That situation changed in 1998 when he published Birthday Letters, 88 poems about his relationship with Sylvia Plath. The book appeared in an unusually large edition: it was the fastest-selling collection of poetry in the history of English literature (over 100,000 copies before the end of the year). Ted Hughes was already suffering from cancer when he wrote the majority of the poems. He died on 28 October 1998.

Unconditional love

Such a steep wall of literature is daunting. What can be added to the dossier? No, I wasn’t really planning to read Connie Palmen’s novel, but on 10 October 2015 I saw on the BBC Stronger than Death, a poignant hour-long documentary on Hughes, with testimony from friends and biographers and for the first time a long interview with Frieda, the daughter of Sylvia and Ted, herself a poet and painter, who had designed the dust jacket for Birthday Letters. This documentary demolished the wall and my prejudices. The next day I bought Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story).

Stephen Spender, W. H. Auden, Ted Hughes, T. S. Eliot, and Louis MacNeice at a Faber and Faber cocktail party honoring W. H. Auden, 23 June 1960.

Stephen Spender, W. H. Auden, Ted Hughes, T. S. Eliot, and Louis MacNeice at a Faber and Faber cocktail party honoring W. H. Auden, 23 June 1960.© Smith College, photo Mark Gerson

It is tempting to see everything that has been said and written about the two poets as elements in never-ending legal proceedings: indictment, case for the defence, case for the prosecution, an irrepressible series of witnesses, with echoes and reports in the media. How did Hughes react? In Palmen’s novel it recurs like a refrain: ‘I have remained silent.’ ‘I said nothing.’ ‘I was silent.’ Hughes’s silence was not absolute. When in the 1970s a letter to the editor appeared in the Guardian, containing the accusation that Sylvia’s grave in Heptonstall, West Yorkshire, the village where Hughes had spent part of his childhood and where his parents lived, was being neglected and the story was taken up by The Independent, Hughes flew off the handle. The letter had been signed by academics and writers, including Joseph Brodsky. Hughes wrote long indignant responses to the two papers, explaining that the gravestone had been removed because ‘libbers’ (who else?) had scratched out the name Hughes no less than four times and that the stone was now in the stonemason’s yard awaiting his decision on how to proceed.

Birthday Letters is not so much a speech in self-defence as a public confession, or better still a commentary on a photo album: sometimes business-like, sometimes in verses where the emotion can be glimpsed. As expressive as all Hughes’s poetry, but for the first time in a relaxed parlando style. What is lacking for the reader who is not thoroughly prepared is coherence and clarity. And that is precisely the aim of Connie Palmen’s novel: to bring clarity. As in Birthday Letters, Hughes speaks in the first person, but his style is more elaborate and direct, less impressionistic and concealing.

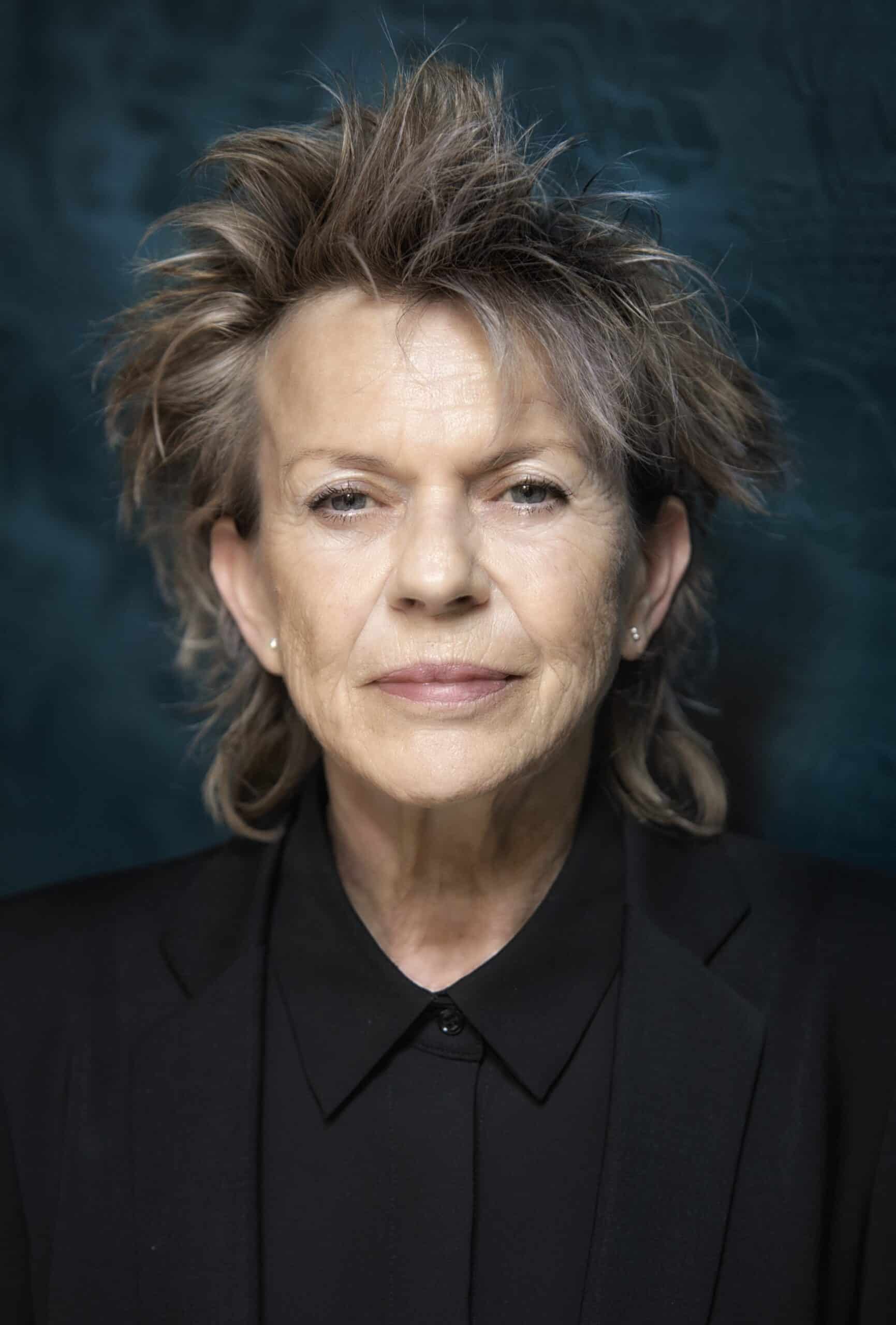

Connie Palmen

Connie PalmenConnie Palmen uses the well-known biographical material available in the many books about Plath; until recently Hughes had to make do with one biography, The Life of a Poet

(2001) by Elaine Feinstein. Ted Hughes. The Unauthorised Life by Jonathan Bate appeared after the publication of Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story). This massive tome, 600 pages long, was rightly criticised because of Bate’s predilection for focusing on the poet’s extramarital escapades rather than his work. (Hughes married Carol Orchard in 1970.) In Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story) the biographical facts are a kind of guideline, the chronological thread around which the novel is woven, but are drowned out by the reflections and comments of the narrator.

The core of Hughes’s story is the constant affirmation that his love for Sylvia was unconditional, that he never questioned that love for a moment, and that in the last weeks of her life there were even plans to move back in together. Through the way in which Connie Palmen empathises with Hughes’s feelings and has him make, for example, the following confession, we enter the field of the novel (cf. the statement by Bernard Crick, the biographer of George Orwell: ‘None of us can enter into another person’s mind; to believe so is fiction’):

‘Everyone around me thought me overprotective of my bride, saw her as possessive, demanding, and jealous, and me as an obedient dog, a sleepwalking bridegroom who couldn’t see how manipulated, drilled, and trained he was becoming. They forgot that everything she saw and felt, I underwent as if I saw and felt it myself. Her pain was my pain, her fears were my fears, except I reacted differently.’

Dominated by literature

Besides the physical attraction – Palmen describes at length their first meeting, when Sylvia kissed Ted on the cheek until he bled and then:

‘We didn’t embrace—we attacked each other. (…) It was cruel, it hurt. It was real. We plundered each other.’

– there was of course literature. The famous first meeting took place in Cambridge on 25 February 1956. A party was being given for the launch of Saint Botolph’s Review, a literary magazine that was to cease publication after its first issue. Hughes had published a few poems in it and Sylvia was so impressed that she knew them by heart and recited bits of them as she threw herself at Hughes. They married a few months later on 16 June, Bloomsday, the day on which the action of Joyce’s Ulysses takes place.

Olwyn Hughes reflected in a mirror as she takes a photograph of her brother Ted, the future poet laureate.

Olwyn Hughes reflected in a mirror as she takes a photograph of her brother Ted, the future poet laureate.© Photograph: Stuart A Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library, Emory University, Atlanta

From the outset then their lives were dominated by literature. Sylvia was Ted’s muse and Ted was Sylvia’s mentor. They read their poems to each other and commented on them. Sylvia typed out Ted’s messy manuscripts until she was able to make up a collection and entered it for an important American debut prize. That collection, The Hawk in the Rain, won the prize and was published simultaneously in England and America: exceptional for a debut. Hughes had begun on a lightning career. The mentorship of the prize-winning poet consisted in his commissioning poems and also stories from Sylvia, since it was one of her ambitions to publish in well-known journals like The New Yorker. Hughes felt she wrote too autobiographically and worried so much about the expectations of those magazines that she did not show herself to her best advantage. He constantly advised her to search deeper in herself for her authentic voice. Plath found that voice at the end of her life, when in Devon and London in difficult circumstances caused by having to care for two children she was obliged to steal a few hours in the early morning to write the poems that were to make her posthumously famous.

Not the last word

In the years when they were still together, their collaboration was so intense that in the archives of the American universities, where their manuscripts are preserved, versions of their poems were found on the back of each other’s rough drafts. During the few years that they lived in Devon, they often wrote about the same subjects. Connie Palmen has Hughes say that at a certain moment the intensity of their collaboration became too stifling and was probably the deeper reason for their estrangement and split. Ironically, in Birthday Letters we find constant echoes of Sylvia Plath’s last poems, exactly as if they are writing on each other’s rough drafts again. A special case of intertextuality, which Connie Palmen expresses brilliantly:

‘In the years following her death and now—now that I’m trying to fill the void left by her suicide with poetry, carrying out a posthumous dialogue instead of a discussion that’s no longer possible, completing the eighty-eight birthday letters to my bride to lay claim to my version of our love, affirming my rightful ownership of my memories, and allowing the poetic version of her story to be echoed in mine—the image often comes back to me of how we sat for the last time together by the fire in the crimson sitting room, and how the flames’ glow clearly showed our words merging; one body, one spirit, a marriage of language.’

Connie Palmen has given a voice to one of the best-known English poets of the last century. She achieves this feat in bravura fashion. The story is believable, incredibly compelling and not at all redundant as I had initially feared. The reader is not given an answer to all the questions. Why, for example, Hughes appointed his sister Olwyn as an intermediary, knowing that the two women were arch enemies and that Olwyn’s opinion after Sylvia’s death even hardened. I read somewhere that Hughes in that way tried to keep the money from her literary legacy in the family. But enough of that: Jij zegt het (Your Story, My Story) is a wonderfully structured book, full of passion and empathy, though most probably not the last word.

Connie Palmen, Your Story, My Story, translated from Dutch by Anna Asbury and Eileen J. Stevens, Amazon Crossing, Seattle, 2021, 206 pp.

This article is a translation of the review of the original Dutch book Jij zegt het (Prometheus, 2015), published in The Low Countries № 25 in 2017.