Abdelkader Benali: ‘The Bastard Language is the Language of the Future’

The bastard language is the language of the twenty-first century because we are the children of a crazy, chaotic age in which the individual has to figure things out for himself. Language adapts to who we are. If language has first to conform to the laws of grammar, it must now also conform to the laws of the street, the laws of migration, the laws of liberalisation. The bastard is on the alert. The one you hear is who I am.

The bastard language embraces new words at the speed of light. Kapsalon (lit. barbershop) for an abundant meat dish with chips and cheese, terroroehoe (lit. terror owl) for the winged creature that terrorises neighbourhoods with its horrific sound, and then there is aanspoelstrand (lit. wash-up beach) where the refugees from North Africa are washed ashore. Every day new items come to the language market, like freshly caught fish. Words that have exhausted their usefulness are just as easily thrown back into the language sea.

Dutch is heading along a motorway where vehicles are entering and exiting at high speed. The quicksilver words join the social motorway via the slip roads of the media and street noise. At the end of the year the new words are listed in the press. The lists are a reminder of the world we were living in. This is who we were, this is what preoccupied us, what annoyed us. Those words are the mirror of what we believed in last year, of how we controlled reality and what we thought of it.

Dutch adapts remarkably flexibly to our linguistic wish to name reality accurately; the strength of the bastard language is that it is never lost for words, hence the habit of quickly reaching for an English loanword when the moment requires it. The nigglers are wrong when they say Anglicisms are an admission of weakness. It isn’t laziness, it’s the powerful, confident way Dutch plays ‘word grab’. Like rivers and seas, the bastard language knows no bounds.

The strength of the bastard language is that it is never lost for words

Our bastard language is a mixture of foreign and local words, of words from the dictionary and words from songs, words from the distant past and up-to-the-minute words, words found in the clouds, low-life words. The bastard language is the thermometer in the bottom. The bastard language is an indicator of the condition of language.

Language is prestige

It was once thought that bastard languages were exotic variants of Dutch. And so they are. They arise when formal language proves inadequate in daily intercourse. It is the secret route to feeling. To understand the origin of the bastard languages we must go abroad.

We’ll begin in the former colonies. In the period of slavery Dutch was the language of the master for the Surinamese. Speaking the language was in itself an act of resistance. Anyone who spoke Dutch could see through the machinations of the rulers. On the other hand, the language humanised power and made it vulnerable. Being able to talk back to the rulers in their own language was the first step towards liberation and emancipation. The elite of independent Surinam prided themselves on speaking better Dutch than the Dutch. Language became a matter of prestige. The Surinamese Dutchman Ricardo Pengel, a doctor at the Radboud Hospital in Nijmegen, told me how he learned Dutch geography in Paramaribo: ‘I knew all the lakes and rivers and canals off by heart. Only when I arrived in the Netherlands and saw those rivers for the first time, did I realise what I had learned in Paramaribo.’

The Surinamese who came to the Netherlands after Surinamese independence brought their Surinamese Dutch with them, interspersed with words and phrases of the marons, runaway slaves, and the Javanese, Chinese and Hindustanis. Under the Dutch surface Sranan Tongo, the language of Surinam, made itself heard like a spitfire. It refused to be forgotten and could never be. The language of the Surinamese was like moksi metti, their national dish, in which various types of meat and vegetables are combined. Moksi metti means mixed meat. In Surinamese one travels through three cultures in one sentence.

Words in the language of Surinam, Sranan Tongo

Words in the language of Surinam, Sranan TongoWhen I grew up in Rotterdam my mother tongue, Berber, was joined by the dominant formal Standard Dutch. At school, we learned the correct pronunciation, with every word approved by pedagogues. At home, we switched to Berber, but that could not prevent the steady encroachment of Dutch. What began in one language could be finished in the other. Anyone who spoke too correctly was looked down on. Prestige was closely linked to street cred. Outside, a different reality prevailed. In the street raw, stiff Rotterdam dialect danced with the Dutch of the Surinamese. Wat seggie? Als ie val dan leggie! Ja toch? (What dya say? If ya fall ya on the floor! Right?)

In the street Dutch freed itself from the tight constraints of formality to be able to sing its polyphonic song freely. It was simply allowed to be. In bastard language liveliness takes precedence over formalism, timing over well-considered periods and humour over seriousness. Bastard language is the currency of the street, which becomes more valuable the more the owner exchanges it. Without the bastard languages, Standard Dutch has no right to exist and will die out. The bastard does not give his father and mother a moment’s rest in his yearning for recognition.

Secret language

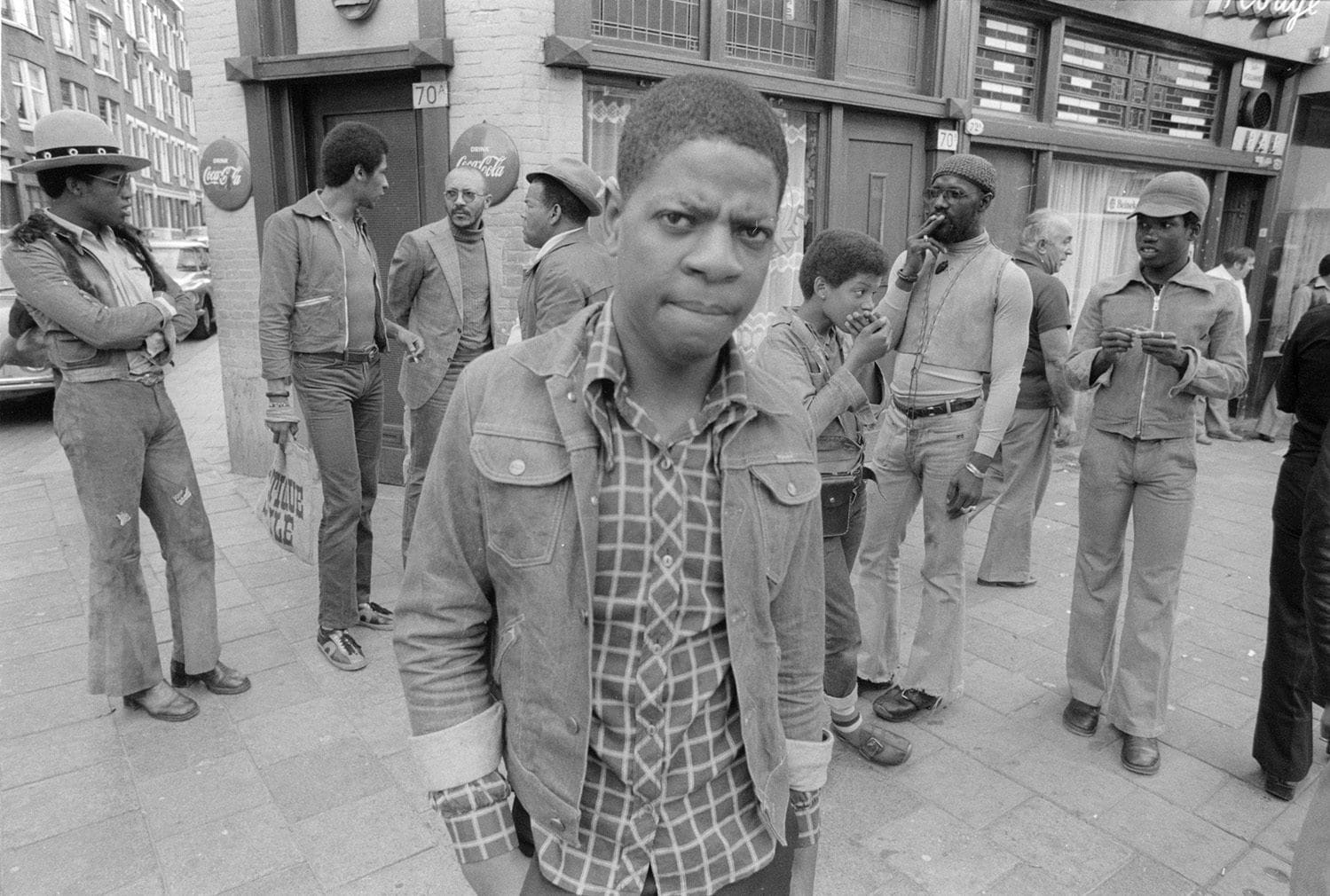

In the street where my father had his butcher’s shop, West-Kruiskade, tough Surinamese guys ruled the roost. They stood in front of the shop, the kings of the street. Their Dutch sounded tough. On their heads they wore Panama hats from Venezuela, gold chains hung around their necks and thick silver rings squeezed their fat fingers. Their language was weighed down just as heavily. Their voices growled as low as a chain saw felling a tree, and when they laughed I heard the tree fall. When they laughed, the wires above the tram line vibrated.

On hot Wednesday afternoons, there was nothing to do in the shop and I eavesdropped on their conversations. At the start, it was incomprehensible because it was so far removed from the Dutch I was familiar with, but little by little I got used to it and actually started to understand it. What happened was that I started to see Dutch as a foreign language, a language that I had to master. And just when I thought I understood everything they turned away from me and never came back, after which other men took their place and the game began again from the beginning. Whenever they had something to discuss in the clan they switched to their secret language, and then the door closed in my face and I again felt like the outsider I had always been. Language could also be a secret language. And I understood that a language that wants to survive has to be reborn each time anew.

Surinamese Dutchmen in the West Kruiskade quarter, Rotterdam, 1975

Surinamese Dutchmen in the West Kruiskade quarter, Rotterdam, 1975© Peter Martens / collection Nederlands Fotomuseum

I heard the thick ‘w’s of the tough guys with the chains around their necks again in the Antwerp Flemish of my cousins in Wilrijk as if they had been to the same pronunciation school. That thick ‘w’ was suppressed on the news and in formal exchanges – where it had to be as thin as watery soup. My cousins did not stick to grammar, they mixed Moroccan and Berber with Antwerp dialect, a potpourri of Flemish restlessness. The new Belgium. As a favour to me, they toned down their language in my presence, started speaking more correctly and became duller. I didn’t care for it at all, but how could I persuade them to be themselves? They were proud of the ability to switch ‘languages’ so fast within one language. It gave them power.

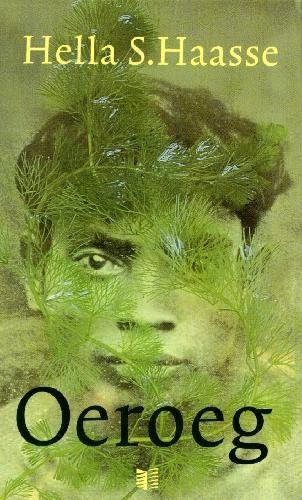

When a language goes travelling, it assumes the protective colouring of the new environment. Spanish, regional, Antwerp, Portuguese and African words fitted effortlessly into that tropical Dutch and the Dutch of my cousins. Dutch’s capacity for absorption was a sign of its vitality. The language’s great open-heartedness also met with resistance: a bastard is not yet an adopted child, it is talked of with shame and the outside world must not know about it. ‘You have no business here,’ Oeroeg barked at his Dutch friend in the novella of the same name by Hella Haasse – this threat that deals a fatal blow to the friendship between Oeroeg and the first-person narrator, is spoken in Dutch, not Indonesian. The last words exchanged between two friends are filled with bitterness. Five words that could not have better summarised the tragic transition from the Netherlands Indies to Indonesia, from a sentiment to a reality.

Oeroeg, the novel of Hella Haasse, is set in the Dutch East Indies, and tells the story of an anonymous narrator growing up on a plantation in the Dutch colony West Java.

Oeroeg, the novel of Hella Haasse, is set in the Dutch East Indies, and tells the story of an anonymous narrator growing up on a plantation in the Dutch colony West Java.In Hella Haasse Dutch changes from being the language of friendship into the language of the enemy. History dons a new jacket. The Dutch disappeared, leaving behind the plantations, balconies and dusty words. Travelling through Java in search of the roots of the Oerol festival on the Dutch island of Terschelling in the tea plantations around Bogor, I pass shops whose signs refer to past Dutch commercial activity. As if nothing has changed. A pharmacy is an apotik (Dutch ‘apotheek’). A garage is a bengkel (Dutch ‘winkel’ = shop) and the cemetery (Dutch ‘kerkhof’), the place where language finally comes to rest, is a kerkop. The Dutch of an elderly Moluccan with whom I strike up a conversation is dusty, formal and far too cultured for the easy-going conversation we are having. That was how it sounded fifty years ago, what I hear is a living fossil.

World language

I shall never forget the man who ran the most famous tango café in Buenos Aires. He had eyes full of fun and a wonderful Latin moustache of the kind that can only be found in those parts. I had taken refuge there with my Argentine publisher – young dude, ponytail, weak left foot in football – to recover from the interviews I had given. Above us hung a photo of the same table, seated at which were the two sacred monsters of Argentine literature: Borges and Sabato.

‘I wonder if the owner has a poster of this?’ and I headed for the man behind the bar.

‘Do you have a poster of that and if so can I buy one?’ I mumbled in English, hoping for the best.

‘What country are you from?’ he asked in amusement.

‘The Netherlands’, I replied and to my astonishment, he broke into fluent Dutch. ‘That photo is not just hanging there for no good reason, they settled a long-standing argument in this café’, and he presented me with a poster. For nothing. I had nothing to say about the poster, but I did about his mastery of the language of the Low Countries. ‘How come you speak such good Dutch?’ His eyes gleamed. ‘It’s a world language, isn’t it?’ He had me there. By giving Dutch this predicate, quite apart from the fact whether it was true or not, he had made me a provincial and himself the true citizen of the world. He quickly reassured me. The owner of the café spent a part of the year in Brabant. ‘With my love.’ So it was another case of love. And the tango danced on. What would Dutch sound like if it were spoken by Argentines? Or Ghanaians? Or Russians?

The Argentinian writers Ernesto Sábato and Jorge Luis Borges

The Argentinian writers Ernesto Sábato and Jorge Luis BorgesThe future of all languages

A strange sensation, being spoken to in the language of home in unexpected places. In some Berber villages in the Rif, they swear in Dutch and count dirhams with a soft ‘g’. Seated on the soft sofas of the Moorish palaces of returned emigrants, they watch the Dutch World Service and dream of chips with mayonnaise, a cloudburst and a sprint on the bike. Across the balcony, one sister yells at the other to ‘Bring back a bottle of coke and a packet of tampons.’ No one can understand them. So they thought.

In some Berber villages in the Rif, they swear in Dutch

Standard Dutch is a myth propagated every evening anew on national television; the rest of the world prefers to speak in as broad a dialect as possible. You don’t hear language, you taste it. On a sandy beach in Al Hoceima there is a cacophony of regional pronunciations, Brabant, Limburg, West Netherlands conurbation, Ghent and Antwerp, all twittering together at thirty degrees in the shade and if I close my eyes and the languages flow into my ears from all sides, they merge into a language I no longer understand, a new language that at some time in the future will assume its fixed form. This must have happened to languages down the ages.

A bastard language diverges from the official language; it is the illegitimate child born of an undesirable courtship between the grand lady and the street urchin, the judge and the whore. In hip hop music the bastard language screams for recognition. In a vital, noisy and fearless mix of street language, pidgin and formal grammatical structures which are played around with to the heart’s content of the speaker, the voice of the new, the unpolished, the explosive energy, demands its place. But the raison d’être of the bastard language is that it will never become official; it shrinks from formal recognition as the bat does from the day. It cannot live in that assigned status. All attempts by Standard Dutch to regularise the language will result in its death. Both sides benefit from this uncomfortable relationship, like two lovers who in their quarrels push each other’s characters to new heights.

The bastard language is the result of a deep love between language and humankind. It is the future of all languages.

This article was previously published in our yearbook The Low Countries 24 (2016).