Against the Status Quo: Louis Paul Boon in a Wider Literary Context

Louis Paul Boon (1912-1979) stands apart from other Flemish writers of his generation because of his insistence on finding his own voice. That distinct voice combines a rootedness in Boon’s own particular Flemish locality — the outskirts of Aalst, a provincial Flemish town — with an emphatic and even aggressive refusal to be bound by dominant literary conventions or dominant political and social ideals. This innovatory distinctiveness must explain in part why Boon’s early works — My Little War (Mijn kleine oorlog, 1947), Chapel Road (De Kapellekensbaan, 1953) — were commercial failures and had to wait until the 196os for readers to become interested in them.

Boon’s work has frequently given rise to literary comparisons by critics and commentators, perhaps because it cannot be readily categorised. Another indication of this resistance to categorisation is the range of authors whose work offers a basis for comparison. On the one hand there is the nineteenth-century Dutch writer, Multatuli, with his critique of the Indonesian colonial enterprise in the layered, apparently chaotic prose of his novel Max Havelaar (1860), but also other great European realist novelists of the nineteenth century such as Flaubert, Dostoyevsky and Dickens.

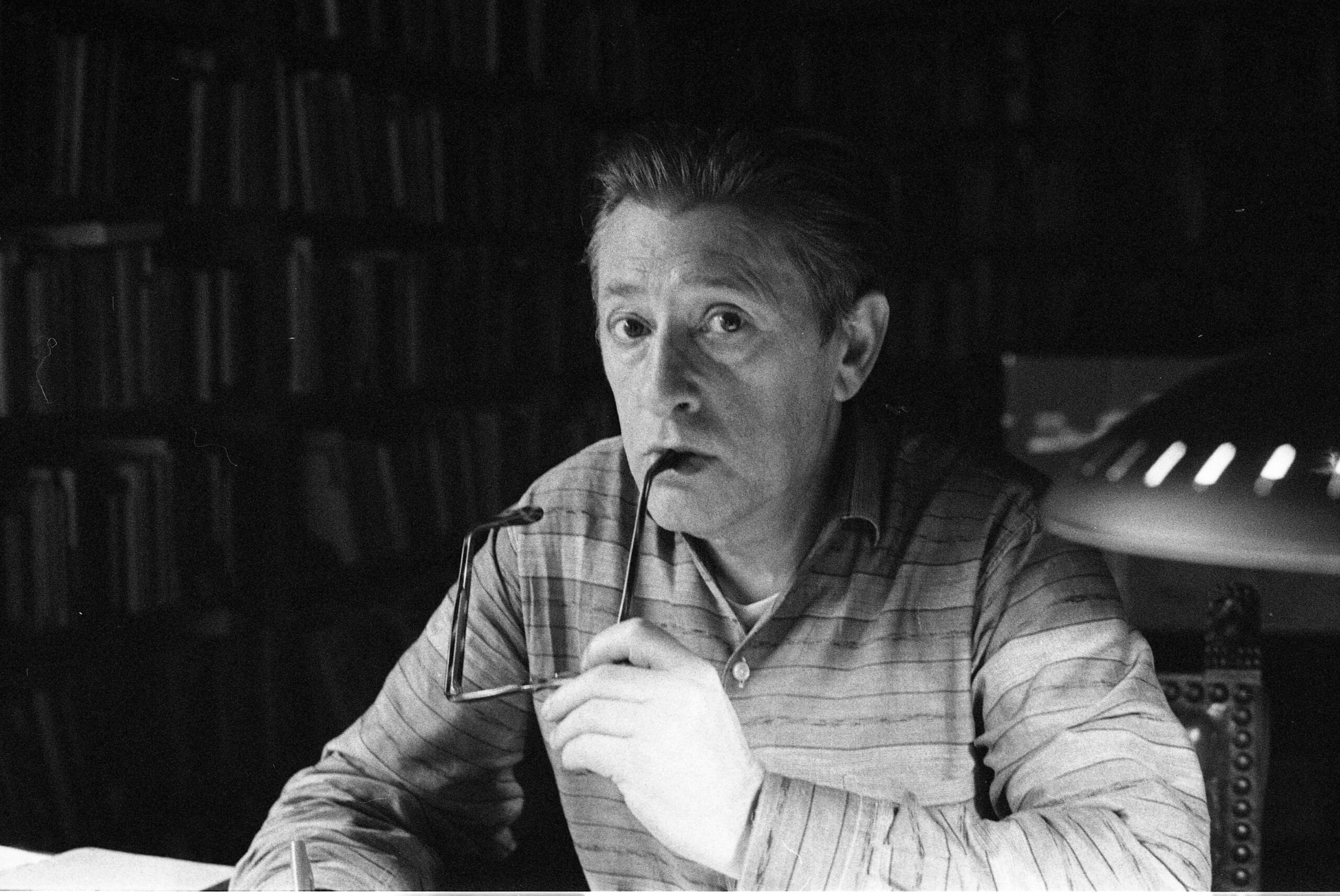

© Jo Boon/heirs Boon

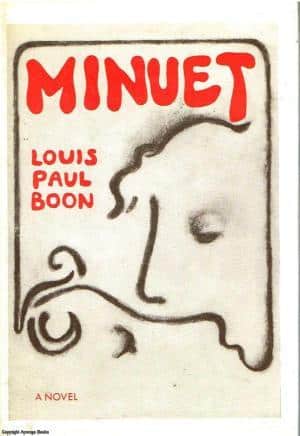

On the other hand, Boon has also been compared with postmodern writers from North and South America, such as Barth and Cortazar, as well as the English novelist John Fowles. This suggests that Boon’s work must contain elements of a broad, critical portrait of society, but what about the realism of the traditional large-scale nineteenth-century narrative? Surely that cannot be combined with the postmodern challenge to the reader, since one works from within literary conventions while the other sets out to undermine and subvert them? This question will be explored in relation to four works by Boon from the immediate postwar period: My Little War, Chapel Road, Minuet (Menuet, 1955) and Summer at Ter-Muren (Zomer to Ter-Muren, 1956).

'Flemishness' and the critique of Flemish society

In asserting himself as a writer, Boon is also asserting the Flemish language and culture, for example through his choice of the outskirts of a provincial town as setting and its ordinary inhabitants as his characters, with their speech authentically reproduced. Boon foregrounds both the social conditions and the range of attitudes and opinions on politics, religion, humanity and literature, all of which are voiced in a distinctly Flemish idiom. My Little War consists of individual anecdotes about how ordinary people coped with the war in their daily lives, suffered hunger and fear, how they collaborated, stole coal, profiteered. The anecdotes are punctuated by more vehement, less coherent outbursts which draw attention to injustice and indifference. My Little War ends with the now famous cri de coeur “Kick the people until they acquire a conscience”.

Boon’s own position when he portrays these working people is that of being one of them: he lives and works among them although, as an observer, he also sets himself apart. By portraying these people rather than an educated elite Boon is making a political point, but this does not mean that he sees them as working-class heroes, as My Little War makes clear. The only time he is prepared to turn a blind eye to their collaboration and opportunism is in the euphoria of ‘The First Hour’, a moving description of being liberated by Allied soldiers.

The essence of Boon’s writing is an acceptance of human weakness

Chapel Road and its sequel Summer at Ter-Muren broaden the portrayal of Flemish society by virtue of their multiple narratives. One of these, a historical narrative, shows the advent of socialism and its apparent failure to bring about radical change in the period from the end of the nineteenth century up to the time of writing. Perhaps the essence of Boon’s writing is that his commitment to the world of ordinary people does not express itself through adherence to any political ideology, but rather through an acceptance of human weakness.

This is embodied in the story of Ondine who is the central figure in this historical narrative with its theme of social injustice. The story shows two possible routes to social emancipation: socialism which involves rejecting the values of the ruling class, and individual upward mobility which involves embracing these values. In Chapel Road Ondine chooses the latter, and uses her sexuality to gain entrance to the world of the factory owners. Precisely because of the limited perspectives offered by her social position, she cannot see that this will not gain her permanent admission, and in the course of the novel this painful realisation is borne in on her until she accepts her position as a member of the proletariat. What is the reader to make of a character who is selfish, ruthless, ignorant, steals and neglects her children, or who kills her first baby, the illegitimate child of one of her landowning lovers? Ondine is monstrous, but the reader sees her in the context of poverty and lack of opportunity which gives rise to her particular survival strategy. It is clear to the reader that there is plenty wrong with such a society, and although a predictable response might be to look for solutions, or embrace social ideals, the realism of Chapel Road offers the reader no such consolation. The local socialists are not idealised. They meet with fierce opposition, not just from the local ruling class, but from ordinary people like Ondine.

Another narrative of Chapel Road and Summer at Ter-Muren is set at the time of writing; it picks up the chronological thread of My Little War, depicting a group of friends in the immediate postwar period who have in common a mood of disillusionment, though they deal with it in different ways. Tolfpoets / Polpoets refuses to take things seriously, Tippetotje reacts with cynicism, Msieu Colson takes refuge in facts and figures, and the music master takes it all too seriously. If the past in the form of the Ondine story and the present do not offer the possibility of realising the dream of emancipation, what of the younger generation growing up during the Second World War? Summer at Ter-Muren paints a worrying picture of them as wild, cruel and anti-social. When the music master plants new trees in his field, the children trample them. Children throw stones at a dog trying to climb out of a canal until it drowns, something which its master on the other side of the canal had been unable to accomplish. When the music master who witnesses this tells his class, they laugh.

In Minuet the negative view of the younger generation is explored in depth through the character of the girl who helps out in the house of the man and his wife. The girl rejects school, religion, hard work, and deliberately sets out to undermine not only the wife’s belief in work and progress but also the relationship she has with her husband. The girl is precocious and in a hurry to taste adult ‘pleasures’. She tells the man she wants to get drunk, and flaunts her sexuality. She is depicted as predatory, watching the man and woman like a hawk, as they go about their seemingly ordinary lives. Although the man is attracted to her and her critical attitude toward society, he is painfully aware of her destructiveness and nihilism which he does not share. Hardly a man of action, he spends much of his time collecting newspaper cuttings about human cruelty which fascinates him. Both the man and the girl look down on the wife and her life of mindless activity. Against a background of an uncaring and hostile society the three characters interact and yet remain isolated.

Boon holds up Balzac and Dostoyevsky as examples for their sharp analysis of social relations and rejection of idealism

It is above all the panoramic view of Flemish society which led to the comparisons with nineteenth-century realist novels, and Boon himself holds up Balzac and Dostoyevsky as examples for their sharp analysis of social relations and rejection of idealism. Like Dickens, Boon uses local detail and colour, while transcending the parochial through his concern with social injustice. Rather than exposing social conditions with social reform in mind, Boon depicts them and exposes the failure of socialism in Flanders. In fact there seems to be an increasingly negative analysis of contemporary society in these novels from the forties and fifties. Ultimately inequalities will not be eliminated because of human nature, and if collective solutions fail all that remains is to look after one’s own interests, which is the path taken by the younger generation.

© Jo Boon/heirs Boon

Narrative innovation

None of this explains the comparisons with postmodern authors, however. In focusing on Boon’s social panorama, the textual complexities of his work have been ignored. Indeed, if one compares Boon’s narratives with the traditional realist novel they seem chaotic, uncertain, rambling, fragmented and generally challenging to the reader. A look at the contemporary reviews of Chapel Road in Dutch and Flemish newspapers confirms this. The literary theorist Theo d’Haen, while stating that he does not wish to make any “inordinate claims for either Boon or Dutch literature” nevertheless demonstrates convincingly that in its technical innovation Chapel Road is comparable to Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Barth’s Letters and Julio Cortazaf’s A Manual for Manuel which were all published in the 1970s. In other words, Chapel Road “does seem to be in the vanguard of a trend subsequently manifesting itself in most other Western literatures”.

The techniques employed by Boon can also be described as postmodern characteristics. However disputed the phenomenon of postmodernism itself might be, there does seem to be an accepted notion of certain typical features: self-reflexivity, a blurring of the boundaries between author, characters and reader, the use of montage, to name a few, all of which have the effect of manipulating the reader into reading more actively since s/he is deprived of a linear plot to follow and rounded characters to identify with. Chapel Road has three narrative strands which interrupt one another: the historical Ondine story, the contemporary narrative and the stories of Reynard the Fox retold.

© Jo Boon/heirs Boon

Reynard the Fox

In the contemporary narrative, a writer character, sometimes ‘I’, sometimes ‘you’, discusses the book he is writing with a group of friends who comment on the emerging text which is, of course, the Ondine story itself. One of the group, Johan Janssens, who is always referred to as ‘poet and journalist’, is writing a series of reworkings of the medieval Flemish stories of Reynard the Fox, and these are also included in the text, forming a distinct, third narrative strand. There are two main ways in which the Reynard stories are integrated in the novel as a whole. First, the many parallels between the character Johan Janssens and the author Boon himself add a self-referential dimension, and second, the Reynard stories themselves echo the view of society and human nature in the other two narratives. The society in which Reynard lives is organised for the benefit of the king and his immediate associates, and the other animals have to find their own survival strategies. Isengrim the bear, being somewhat slow-witted and lacking in deviousness, comes off badly, whereas quick-witted Reynard has the last laugh at everyone else’s expense.

Boon’s / Johan Janssen’s Reynard stories are in a sense extraneous text which gained a separate published existence as Brothers-in-Arms (Wapenbroeders, 1955), and as such are an example of a form of montage. Minuet, of which montage forms a structural ingredient, has been compared to the novel U.S.A. (1937) by the American writer John Dos Passos since both works incorporate newspaper cuttings, though to different effect. The man in Minuet spends his spare time collecting cuttings, and the text has an unbroken string of cuttings running parallel to it. Although the two text types are kept separate, there are strong echoes of the man’s perspective – the world of the cuttings presents a sick society. The presumably factual nature of the cuttings impinges on the way the fiction is read, generalising the particular stories of the man, woman and girl. Similarly, the three different narratives of Chapel Road make it impossible to give a parochial reading because of the generalising effect created as each narrative strand affects the way the others are read. Far from being gratuitous, the technical innovation can be seen to reinforce the social message of Boon’s work.

© Jo Boon/heirs Boon

More than anything else, Chapel Road and Summer at Ter-Muren are novels about writing, not just writing in general, but the genesis of the novels themselves which is depicted as a democratic process with the group of friends responding to what has been written so far and offering suggestions. When Boon’s wife tells a story, she suggests a title: “god helps those who help themselves”, and sure enough, that is the title of the section itself. In Summer at Ter-Muren, the characters themselves compose some of the story of Jan de Lichte’s band of robbers which replaces the Reynard stories. Johan Janssens writes journalistic pieces about the historical background of 1750; Tolfpoets / Polpoets digs around in historical documents of the period; and Tippetotje writes an erotic fantasy involving a beautiful woman in a stagecoach held up by the highwaymen. It is this rejection of traditional auctorial authority that has given rise to the comparison with The French Lieutenant’s Woman, although in this case the reader is to choose his / her own ending, or accept all the endings proposed by the narrator.

Returning to the question of how Louis Paul Boon can inspire comparison with writers as disparate as Dickens and Fowles, the common factor is their desire to undermine the status quo, whether social or literary. Boon’s distrust of authority finds expression both in his choice of subject matter which is fiercely critical of those in power, and in his narration itself with a narrator who is as far removed as possible from the traditional all-powerful narrator with his seamless plot and neat ending.

This article first appeared in The Low Countries – 1998, № 6, pp. 232-237