‘Aleksandra’ by Lisa Weeda: Little People as Pawns in Politics

Lisa Weeda has in recent weeks emerged in Dutch news outlets as an expert on the war in Ukraine. This has to do with her excellent debut novel Aleksandra, which tells the story of a divided Cossack family.

Now that Ukraine has been dramatically thrown into the spotlight, Lisa Weeda’s debut novel Aleksandra seems to have taken on a second life. In addition, the book has been shortlisted for the Libris Literature Prize. This is well deserved, because Aleksandra is a tour de force, an imposing novel with many layers, interspersed with history large and small, in an imaginative style that swings the reader back and forth between then and now, between The Hague, Moscow, Kyiv, Odesa, and Luhansk, from kitchen table to battlefield and back again.

Lisa Weeda

Lisa Weeda© Geert Snoeijer

We meet narrator Lisa in August 2018, at a border crossing between Ukraine and the Luhansk People’s Republic, one of two breakaway states in the far east of Ukraine established in 2014 that are recognised only by Russia. Lisa tries to persuade a soldier to let her through, in vain. She is persistent because her grandmother Aleksandra has entrusted her with a mission. She has to bring her uncle Kolja a special cloth, on which their family tree is embroidered in red and black. But since he may have died in 2015 during the battle for Luhansk, she is in fact looking for his grave. Her 94-year-old grandmother Aleksandra was deported from Luhansk by the Nazis in 1942, when the city was still called Voroshilovgrad.

The soldier at the border will not be swayed, even when Lisa makes a point of their shared hatred of Nazism. But when someone steps on a landmine in a field, Lisa seizes her chance to cross amid the havoc. She is helped by a kind old man, but stumbles anyway and has a bad fall.

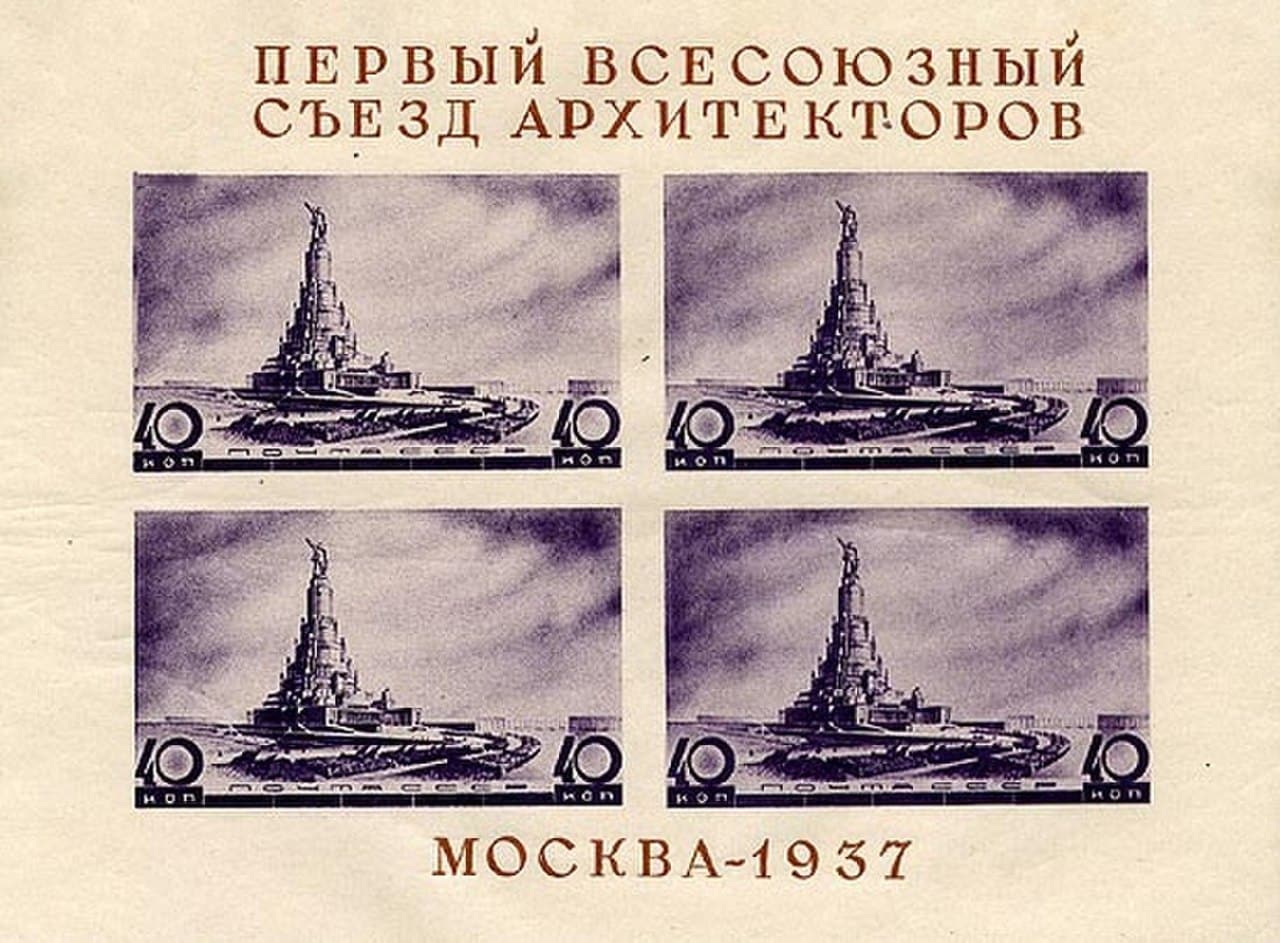

One of the designs for the never realised Palace of the Soviets

One of the designs for the never realised Palace of the Soviets© Wikipedia

When she wakes up in the next chapter, she finds herself in the “Palace of the lost Cossack”, an imaginary place that bears a striking resemblance to the Palace of the Soviets Stalin wanted to build in Moscow on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. This megalomaniac project never got off the ground, and after World War Two its dug-out foundations were used as a gigantic outdoor pool.

In the Palace, Lisa meets her great-grandfather Nikolaj, Aleksandra’s father. They talk as they wander through the gigantic complex, look at the social-realist symbolism of the art on the walls, end up in interrogation rooms and eventually in that swimming pool. The chapters set in the Palace are full of magical-realist fragments, in a clear reference to writers such as Nikolai Gogol, who wrote in Russian but was of Ukrainian origin. Chapters from Luhansk, set during the conflict of 2014 and its aftermath in the following years, are interspersed with chapters from the Palace.

That Palace and meeting her great-grandfather is a wonderful device Weeda uses to tell the impressive history of her family. Her family is descended from the Cossacks, an ancient nomadic people who roamed the steppe and received privileges from the tsar in exchange for mercenary service. Some eventually settled as farmers in Ukraine, where they cultivated mainly wheat.

The story of the Temnikovs is also the history of Ukraine

Thus we learn the story of the Temnikovs, which is also the history of Ukraine. And it is heart-breaking. The family is now being torn apart by the war in the Donbas, the eastern region bordering Russia. Relatives drift apart or disappear, and it has always been like this. They are typical victims of politics, little people who serve as pawns in the geopolitical aspirations of dictators such as Hitler, Stalin, or Putin.

Lisa is herself a product of those great entanglements. Her grandmother Aleksandra had been deported to Germany by the Nazis in 1942 as a teenager, to work at a factory of IG Farben, the chemical giant that produced the Zyklon B gas with which Jewish people and other victims were gassed during the Holocaust. After the Second World War, she eventually ended up living in the Netherlands.

The scene in which Nikolaj says goodbye to his daughter on the train platform is simultaneously hard-hitting and loving. Weeda makes clear here, without becoming emotional, what war does to families, to people. The description of Stalinist rule and how brutally mistreated the people of Ukraine were in the 1930s is also apparent through their family history. The passage in which Aleksandra, as a young girl, must choose which of their two horses can stay on the farm, and therefore which must go to work at the kolkhoz, one of the new collective state farms set up under Stalin, is particularly powerful.

Throughout, the narrative is full of symbolism. We learn about the existence of Cossack deer, always wounded and with an arrow in their body, harbingers of death. Those deer keep cropping up throughout the book. And we learn the meaning behind the red and black lines on Lisa’s grandmother’s embroidered cloth.

With Aleksandra, Weeda has written not just a gripping family novel. It is a book that provides insight into the history of an entire country on the basis of one family. She does so without exaggerating or romanticizing the violence of war, without dramatizing the emotional family elements, and with a layer of magic-realism that turns the book into a kind of feverish dream.

An excerpt from ‘Aleksandra', as translated by Paul Vincent

Palace of the lost Cossack

Wide marble steps stretch out on either side of my body. I get up and go up the stairs as fast as I can. The steps are so high that I have to jump. When I catch my breath on a landing, I see a gigantic tower. A hysterical birthday cake, a narrower version of the Tower of Babel. The colossus consists of six large round layers. On top is a statue of Lenin. Each floor is lined with columns. On top are statues: people, five times my size. They carry flags and march forward, I see workers and children, kolkhoz girls, boys carrying chisels and hammers. They are dressed in two-piece overalls, dungarees, aprons over dresses, headscarves, and caps. Lenin makes up almost a quarter of the building and points into the distance, towards the checkpoint in Ukraine, towards the West, away from the war zone, away from the border with Russia. I follow his finger and see the soldier’s helmet move at the edge of the wheat field.

Is he still following me? Behind the first row of columns, a wooden door slides ajar with a creaking sound.

“Hey, there!” the voice hisses, “what are you doing?”

A head peers outside. I recognize the face from a black-and-white portrait that hangs above my grandmother’s bed.

“Holy crap,” I whisper, “Nikolaj.”

He doesn’t look a day older than on the photograph: a few long wrinkles on his forehead, crow’s feet, a trimmed moustache, dark eyebrows, and a sharp jawline. He beckons with his small hand. I look at Lenin one last time.

“What is he doing here,” I call, “isn’t that man a century late?”

“Does it matter,” Nikolaj rushes, “just come inside.”

I run up the stairs and slide across the gleaming landing to the door, out of which grains of wheat are streaming.

“This all has to go back inside,” he says, concerned.

I kneel before the door. I make a bowl with my hands, carefully scooping up the grains.

“Faster, as fast as your young body is able, my girl!”

Using my hands like little snowploughs, pushing the grain in front of me, I hear the soldier hollering that I’m in the middle of a minefield and should stay still.

“I can’t see exactly what you’re doing, but listen. Stop. Moving!”

For a moment I hesitate about whether to go in, or whether just to shut my eyes and stop moving, as the soldier says, play dead, out in the field, until someone fetches me, but when I look into my great-grandfather’s kind blue eyes and hear the soldier approaching behind me, I sweep in the last of the grain and wrench myself into the building.

Once inside, I push the heavy door shut with Nikolaj. He bends his knees and exhales deeply. I take off my bag and let myself fall back into the grain. The vaulted ceiling and walls are covered in frescoes: people waving red flags, children in white uniforms with red neckties. They parade on boulevards as wide as the six-lane motorway that runs through the middle of Kyiv and where military parades are held on 9 May. The corners of the ceiling are decorated with hammers and sickles, I can see red stars, gilt frames, and stone banners. Nikolaj reaches out a hand and pulls me up.

“Finally,” he says, “after all this time.”

Lisa Weeda, Aleksandra, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2021, 352 pages.