Alice Wong Weaves Together Information and Stories

Alice Wong (b. 1989) calls herself a story designer. She grew up in Hong Kong but has lived and worked in the Netherlands for a number of years. Chinese culture still plays a big role in her work, but what she is really interested in is something much more abstract and penetrating: how reality is shaped.

‘You write one thing in order to talk about something else’. It is almost an aside in the Argentinian author Maria Gainza’s book Optic Nerve, but it would be an excellent motto for Alice Wong’s work. Her video Weaving Stories (2018) – in partnership with thonik and Alexandre Humbert – begins as a rather traditional documentary about two Chinese weavers, both women. The emphasis appears to be on the process and tradition of weaving. But after a while they talk not only about their work, but also about Chinese society. One of them remarks that with their salary they could never afford to buy these fabrics. They even talk about their love lives. This explains the second meaning of the title, Wong weaves stories, perspectives and subjects through each other, until they appear to form a single entity – because you can pick out the different threads and see where they take you.

Borrowing images

Wong obtained a Master’s in Information Design at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, a course involving a lot of research, which is aimed at teaching understanding and information design in the age of the internet. She had lived in the Netherlands before, until she was four. But then her father died, and she returned with her mother to Hong Kong, where her parents were born. She returned to the Netherlands to study design, ending up in a city where the boundaries between autonomous and applied art are flimsy.

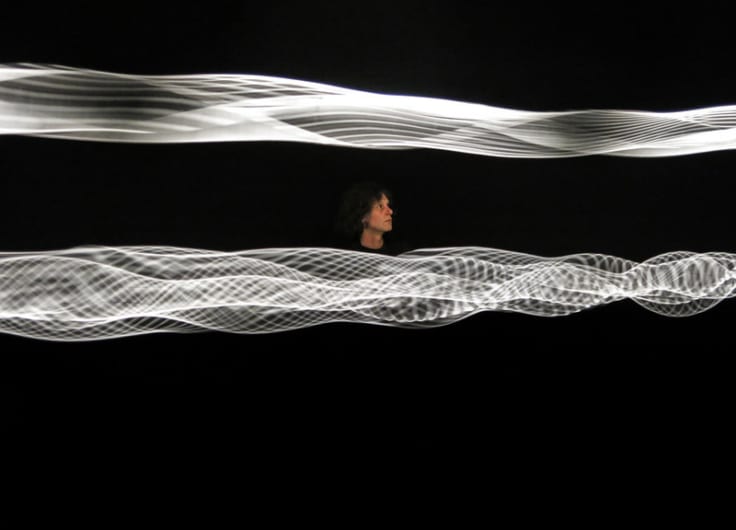

Alice Wong, Weaving Stories, 2018

Alice Wong, Weaving Stories, 2018That is evident not only at the art academy, but also in the often-multidisciplinary exhibitions at the Van Abbemuseum and Mu, in Eindhoven, two places where Wong has exhibited as well. She refers to herself as a story designer, but her work shares more similarities with video and media art than with design. You could call her a hybrid designer/artist, but perhaps fluid would be a better word. She seems to switch easily from pop culture to geopolitics, from a personal story to an awkward, abstract question: how does understanding actually work?

Wong’s videos share a thematic link but come over much more strongly as complete entities

For the larger part of her oeuvre Wong has worked with ‘found’ images, using fragments from news and current affairs programmes as well as animated and feature films. Other people’s images interest her because of their rhythm and sound, for example, but also because of the background to them. In a certain sense her way of working fits into a broader trend in video and media art, prominent representatives of which are the German artist Hito Steyerl and the Dutch duo Metahaven.

They often make long, layered video works that exist largely of borrowed images. Geopolitical and economic themes are dealt with in a non-linear, associative way to imitate the fragmentary, intermittent provision of information via, for example, the internet. Viewers must find their own way through it. Wong’s videos share a thematic link but come over much more strongly as complete entities. Appearances can be deceptive though.

Disintegrating stories

The difference with artists like Steyerl and Metahaven is related to something Wong’s partner Aryan Javaherian (b. 1991) says; he is himself a design strategist and works closely with her. Javaherian believes that people’s capacity to understand information has increased enormously, thanks to mobile phones and the internet. The speed with which we process information and move on is high, whereby we make our own sort of ‘entity’. Wong links that situation to socially relevant themes and research.

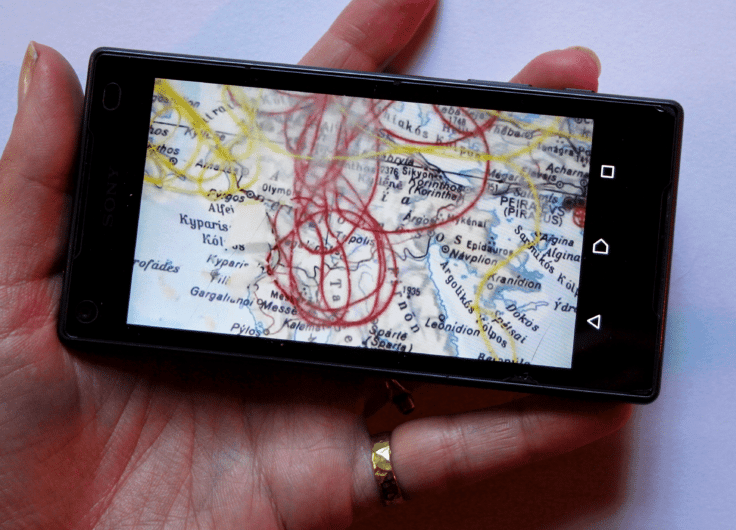

Alice Wong, Double 11, 2018

Alice Wong, Double 11, 2018© Nicole Marnati

A good example is the video Double 11 (2018), which Wong made with Javaherian. In principal, the video loop has no beginning and no end, and shows images on seven different screens. It must be possible to come into the exhibition room at any time and follow the story without too much difficulty, just as, on the internet, you also go from one news broadcast or YouTube video to another.

Double 11 is a ‘story’ that is apparently told coherently, like a news item. The video is basically about the Chinese Singles’ Day – a festival that takes place every year on 11 November – and how it was quickly hijacked by Alibaba, the Chinese company that runs the world’s biggest web shop. The company has turned the day into a feast of commercial consumption on a gigantic scale.

Double 11 is also about Alibaba’s co-founder/face Jack Ma, about how the idea of a web shop had to be reconciled with Chinese culture, and many, many more (sub) subjects. Fragments of TV interviews with Ma alternate with the singer Jessie J singing her worldwide hit ‘Price Tag’. On the one hand, her slick show suits the massive proportions that Bachelors’ Day has taken on. On the other, she sings something that clashes with Alibaba, ‘It’s not about the money / We don’t want your money’. The concert fragment leaves you scratching your head – what are you watching actually? Watch it again a few times and Ma appears to contradict himself regularly too, just like the montage of the images. What was a coherent story seems to disintegrate.

Alice Wong, Reconstructing Reality, 2015.

Alice Wong, Reconstructing Reality, 2015.The characteristic tension between whole entity and fragment in Wong’s work is well illustrated in Wong’s graduation work Reconstructing Reality (2015). At first sight, this moving video is mainly about the death of Wong’s father. She was four at the time. Her mother had always been rather vague about the circumstances, so she went in search of the truth. The video ends with the discovery that her father was murdered – not why or by whom.

But that is not what Reconstructing Reality is about either, it is really about the question of how that event and its discovery have influenced Wong’s perception of reality. As we hear her voice recounting her search, we see a host of images from cartoons, feature films, and video games. At first sight the pop culture images seem to clash with the personal story, but in fact they are very close to Wong’s attempts to form a picture of what happened.

She tells me, for example, that she tried to find out what sort of pistol was used to kill her father. But that information did not help her to imagine the shooting, whereas the films she had seen did. By borrowing images from the films, she got much closer to what was going on in her head.

Propaganda soap

Although Chinese culture plays a major role in much of Wong’s work, she should not be seen as an (emigrant) artist ‘opening up’ her country of origin for a western audience. Her main theme is understanding, and it feels natural for her to take subjects that are close to her as her starting point.

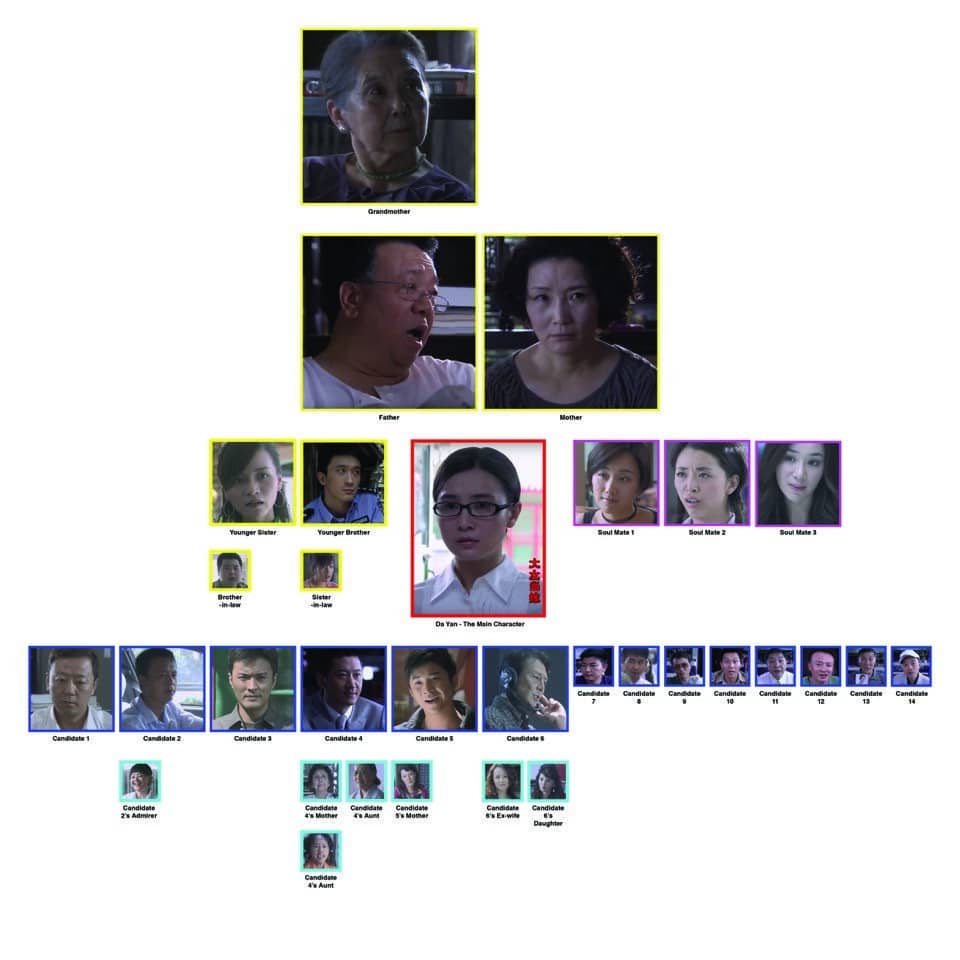

As this article is being written, she is working on a new project with Javaherian, Marriage Matters. The working title was Leftover Women, a reference to highly educated Chinese women who are over twenty-five and still single. Due to the one child policy there are now more men than women in China, and the many single men in the countryside are the source of a major problem of aggression. The government is trying to solve it, to some extent, by persuading the ‘leftover women’ to marry.

Marriage Matters uses images from a popular soap about a woman in her thirties who is ‘still not’ married. As a result, her family worries about her future. With these pictures Wong and Javaherian have created an interactive story – like, for instance, the Netflix film Black Mirror: Bandersnatch (2018) – in which members of the audience take over the role of the woman.

Alice Wong, characters for Marriage Matters, 2019

Alice Wong, characters for Marriage Matters, 2019With this project Wong shows very clearly how propaganda shapes reality. An ideal image is circulated that has real consequences: worried family members, for example, or Chinese women who end up emigrating to avoid an unwanted marriage. Marriage Matters is typical of Wong’s oeuvre, with which she recognisably demonstrates how terribly closely reality and representation are linked.