Allart Van Everdingen, the Man Who Fell in Love With Waterfalls and Spruce Trees

After travelling through Norway as a young man, the Alkmaar artist Allart van Everdingen (1621-1675) fell under the spell of the rugged mountain landscapes of Scandinavia. The impressive natural environment with its waterfalls, log cabins and spruce trees would inspire him for a lifetime when painting, drawing, and etching. Exactly four hundred years after his birth, he now has his very first retrospective in the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar.

For a medium-sized museum, organizing expensive blockbuster exhibitions makes little sense. The Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar has proven for many years that concentrating on its own collection and presenting artists who were born or who worked in the city in question is particularly fruitful. Several seventeenth-century Alkmaar artists have already been presented in monographic exhibitions: Claes Jacobsz van der Heck (in 2015/16), Caesar van Everdingen (in 2016/17) and Emanuel de Witte in (2017/18). These painters have now definitively secured their place in art history thanks to the extensive and richly illustrated exhibition catalogues in which specialists in different fields collaborated.

Portrait of Allart van Everdingen by Arnold Houbraken, 1719

Portrait of Allart van Everdingen by Arnold Houbraken, 1719© Wikimedia Commons

Now it is the turn of Caesar van Everdingen’s younger brother, the landscape painter Allart van Everdingen (1621-1675), to present himself in his native city.

A very large number of painters were active in the Dutch Republic. If they wanted to gain a foothold in the free market, it was essential to specialize and excel in a certain type of art. While Caesar was a history painter who contributed to the decoration of the Oranjezaal in Huis ten Bosch, his brother Allart chose landscape painting.

His first teacher in this field was landscape painter Roeland Savery in Utrecht. Subsequently, Allart was apprenticed to landscape painter Pieter de Molijn and/or marine painter Pieter Mulier I in Haarlem. In 1640 he returned to Alkmaar as an accomplished master and started painting Dutch seascapes. At the beginning of 1645, he married a girl from Haarlem, Janneke Cornelisdr. But before settling down and starting a family, he realized a plan that was not so obvious and for which he probably saved money: not a study trip to Italy, like most of his colleagues, but a study trip to Scandinavia. That journey must have taken place in 1644.

Norwegian Scenery with Rushing Stream and Castle, early 1660, oil on canvas

Norwegian Scenery with Rushing Stream and Castle, early 1660, oil on canvas© Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

Scandinavia as a source of inspiration

Allart’s interest in the exotic mountain landscape undoubtedly arose during his apprenticeship with Savery. At the behest of Emperor Rudolf II in Prague in 1606 and 1607, he had travelled through Tyrol to capture the Alpine landscape. Those mountain landscapes became Savery’s trademark.

Christi Klinkert, the curator of the Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar and organizer of the exhibition, explains in a clear essay that a trip to Scandinavia was practically feasible for a Dutchman. There was a lively trade with Norway, which at that time was a province of Denmark. Dutch and Frisian merchants exported foodstuffs, textiles and Gouda pipes and mainly took back wood from Norway for use in Dutch shipbuilding and carpentry. Dutch ships on their way to the Baltic area also called at ports on the Norwegian coast. There was therefore every opportunity to go to the North from the port city of Hoorn, for example.

About sixteen drawings that Allart made in Norway have been preserved. The names of places he sometimes noted make it possible to somewhat reconstruct his journey. In any case, he visited the coastal towns of Langesund and Risør and the region around Gothenburg: the village of Mölndal, fortress Bohus and the waterfalls at Trollhättan. That area was Danish at the time but was annexed to Sweden in 1645.

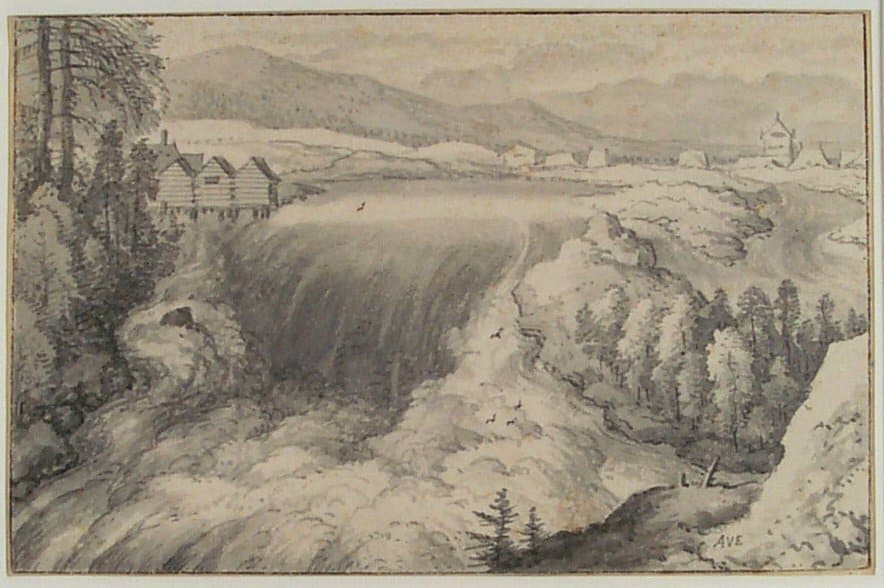

Waterfall near Trollhättan, c. 1644, pen and brush and gray ink, wash

Waterfall near Trollhättan, c. 1644, pen and brush and gray ink, wash© Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

His drawings of mountains, pine forests, waterfalls, watermills, and log cabins laid the foundation for paintings that he would work out when he returned and settled in Haarlem with his wife in 1645. The first paintings with a Scandinavian landscape were created in 1647, two years after Allart had settled in Haarlem. One of those early works with a Scandinavian landscape, the monumental Mountain Landscape with River Valley from 1647, is impressive because of the contrast between the river flowing into the valley and the high, inaccessible rocks, topped by a few lonely spruce trees.

Mountain Landscape with River Valley, 1647, oil on canvas

Mountain Landscape with River Valley, 1647, oil on canvas© Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

The two puny figures of travellers in the lower right corner accentuate the power of the wilderness. While landscapes were traditionally painted on a horizontal plane, Allart soon introduced a portrait format with a high horizon, in which the enormous waterfalls, in particular, came into their own, such as his Norwegian Landscape with Waterfall and Watermill from 1650. The watermill is built from rough logs, just like the typical Norwegian log cabins. The small figures of three men and a dog stand on the rocks looking at the fast-flowing water.

Norwegian Landscape with Waterfall and Watermill, 1650, oil on canvas

Norwegian Landscape with Waterfall and Watermill, 1650, oil on canvas© Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemälde sammlung, Munich

About 140 of the 160 landscapes painted by Allart contain Scandinavian elements. But how realistic were those paintings really? That is the subject of Klinkert’s second essay. The conclusion is that Allart, like almost all other artists of his time, adapted, combined, and moved the elements from his drawings in order to obtain an attractive and balanced composition, often in line with existing pictorial traditions.

He had already become acquainted with the combination of a colossal mountain wall and a low river landscape in Savery’s work, but in a much smaller format. Log cabins, waterfalls, and watermills Allart drew from nature, but in his paintings, he adapted the locations and added figures for the dramatic effect that are too small in relation to the rocks and trees. His whimsical and virgin landscapes – whether they were true to nature or not – matched the fascination with the exotic that arose in the seventeenth century thanks to the increase in international trade.

His landscapes were particularly popular as wall decorations. In this way, Dutch citizens could let their gaze travel through these un-Dutch mountain landscapes from their armchairs and let their imaginations run wild.

Inspiration for Romantic painters

In 1652 the Van Everdingen family moved to Amsterdam, where more wealthy merchants and art lovers lived, and sales were therefore greater. One of his patrons there were the brothers Louys and Hendrick Trip, very wealthy merchants who made a fortune selling Swedish iron, copper, cannons, and other weaponry. Around 1662 they commissioned Allart for several Scandinavian landscapes that were placed above doors and for a particularly large painting that shows a panorama of the factory site of the Trip family in the Swedish Julita Bruk in Södermanland. In accordance with the wishes of the clients, the panorama is undoubtedly strongly documentary in character and may have served as a kind of business card of gigantic dimensions in their home. You can see mines, smoking furnaces, forges, and foundries, with cannons produced in the foreground. Allart probably composed his painting based on information from the Trip brothers and drawn maps.

Hendrick Trip's Gun Foundry in Julita Bruk, c. 1662, oil on canvas

Hendrick Trip's Gun Foundry in Julita Bruk, c. 1662, oil on canvasRijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Allart’s painting colleagues were also impressed by his Norwegian depictions of firs, log cabins and waterfalls. Because of his example, the famous Jacob van Ruisdael also started incorporating raging waterfalls into his work also choosing a portrait format for his dramatic, monumental landscapes. Allart’s influence was great as well on the later painting of German Romanticism. One of his greatest admirers in the first half of the nineteenth century was the Norwegian Johan Christian Dahl, who worked mainly in Dresden.

Interest in Dutch industry

While Allart also concentrated on painting Dutch waters and landscapes, he also needed new inspiration. Around 1655 he travelled to the Ardennes, which was the most accessible area with mountains for a Dutchman. Compared to rugged Norway, the Ardennes will undoubtedly have seemed much more civilized to him. Of interest are the drawings he made of various wells that still exist in Spa, from which the famous Spa mineral water is extracted.

Allart’s Scandinavian landscapes were a novelty with which he became famous, and this will rightly be the focus of the Alkmaar exhibition. The exhibition and catalogue also emphasize the versatility of this artist and pay additional attention to his many Dutch landscapes, sea and river views, such as View of Alkmaar from the water of the Zeglis, which shows his great talent for painting water features and high cloudy skies. Typical for Allart is the depiction of the activity on and around the water. His interest in the Dutch industry is also reflected in other paintings and drawings.

View of Alkmaar from the Zeglis, undated, oil on canvas

View of Alkmaar from the Zeglis, undated, oil on canvas© Fondation Custodia, Frits Lugt Collection, Paris

About 650 of his drawings are still preserved. Most of it was not study material, but intended as independent works of art, for which high prices were paid. Allart introduced a special type of large-format drawings (approx. 18 x 30 cm) for the free market, which he worked out carefully and updated with various colours of watercolour. About half of them represent Scandinavian landscapes, the other half Dutch landscapes, and cityscapes. For those who could not afford an oil painting or drawing, Allart also started making etchings with imaginative Norwegian landscapes in his Amsterdam time. The catalogue contains a very informative essay by Yvonne Bleyerveld about the drawings, while Erik Hinterding treats the prints in detail.

Drawings of Reinaert de Vos

Finally, Allart turns out to have another unexpected side. Towards the end of his life, he produced many drawings and a series of 57 prints illustrating the famous story of Reinaert de Vos, the Middle Dutch epic in which the animal world functions as a mirror for general human behaviour. As a small, separate exhibition, his drawings from the British Museum in London will be on display for the first time alongside prints that Allart made himself based on these drawings. Some of these are mezzotints, again something special, because Allart was a pioneer in this etching technique. The essay by Marjan Pantjes is devoted to his portrayal of the Reinaert de Vos epic.

The Fight between Reynard the Fox and Isengrim the Wolf, etching, third state

The Fight between Reynard the Fox and Isengrim the Wolf, etching, third state© the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Paris (Auguste and Eugène Dutuit Bequest, 1902)

The content and meaning of Allart van Everdingen’s art are also accessible to an English-speaking public, because the catalogue is available in both Dutch and English.

Allart van Everdingen (1621-1675). The Rugged Landscape, Stedelijk Museum Alkmaar, 18 September 2021 – 16 January 2022.