Amsterdam is Everywhere. The Legacy of the 1928 Olympic Games

The 1928 Olympics were held in Amsterdam, the only time they’ve taken place in the Netherlands. There is not much left to see nowadays, but fortunately, there is still a visible legacy here and there. No matter where you are in the world, the Amsterdam Games have left their mark – probably even in the street you live in.

Precisely one hundred years ago, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided the 1928 Olympic Games would be held in Amsterdam. At a congress on 2 June 1921, the city was chosen over a number of American competitors, some of whom did not agree with the selection. What they didn’t know was that, behind the scenes, a secret baronial agreement had been made. IOC president Baron Pierre de Coubertin had signed a deal with Dutch IOC member Baron Van Tuyll van Serooskerken. As a result, Amsterdam became the sporting capital of the world for a few months in 1928.

Aerial view of the Olympic Stadium during the opening of the Olympic Summer Games of 1928

Aerial view of the Olympic Stadium during the opening of the Olympic Summer Games of 1928© Wikipedia

A sporting city of stone

Architect Jan Wils was responsible for building the Olympic Stadium. Luckily, that is still functioning in 2021. In fact, Amsterdam wanted to demolish the stadium in the 1980s to make way for housing, but after a long series of public actions, they were prevented from doing so. The Marathon Tower still stands on the square in front of the main entrance. It is a historic location, because, on that tower in 1928, the Olympic fire was lit for the first time in history. It was Wils himself who imagined the fire, to ensure the entire city would be able to see the Olympics were in full swing. The Olympic fire is therefore a Dutch invention, albeit without the torchlight procession from Olympia at the time. That only happened for the first time in 1936, as a propaganda stunt by the National Socialists.

The Olympic Stadium was at the heart of this most compact of Olympic Games, with all of the other important stadia in close proximity. Only the rowing, shooting, sailing, road cycling, marathon and equestrian field events took place elsewhere. Directly across from the Olympic Stadium stood another stadium that had been constructed in 1914: the Netherlands Sports Park. Two temporary halls were built on the Stadionplein

for the boxing, weightlifting and fencing competitions. And there was a swimming pool, destroyed immediately after the games, much to the frustration of the team from Amsterdam. The rest of the structures have also disappeared, except for the Olympic Stadium and Marathon Tower.

The Olympic Stadium and Marathon Tower today.

The Olympic Stadium and Marathon Tower today.© Wikipedia

The stadium area was nicknamed “Wils’ creation” in 1928. After the Olympic Games, the architect received worldwide acclaim and numerous awards. The leading newspaper, Het Vaderland,

called his work ‘the proof of Dutch strength’. The magazine Revue der Sporten

talked about a sports city made of stone. ‘A city in itself, spacious and large, just as Amsterdam is spacious and large.’

Watery heritage

The Olympic sailing contests of 1928 took place on the northeast side of town, on the IJ, the river that flowed through Amsterdam. That water still flows between the new IJburg district and the picturesque dike village of Durgerdam, a memento of the undulating heritage of 1928. If today’s Steigereiland had existed then, it would have been a fantastic place from which to watch those matches, just like the bridge at Schellingwoude.

Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana visit the Olympic Stadium

Dutch Queen Wilhelmina and Princess Juliana visit the Olympic Stadium© City Archives Amsterdam

Two competition locations were provided by the Royal Dutch Sailing and Rowing Union (Nederlandsche Zeil- en Roeivereeniging) which, in 1928, had more experience with such events than the IOC itself. The twelve-foot sloops competed at Durgerdam, the 6- and 8-metre classes were held further north, towards Uitdam. In the 6-metre, Crown Prince Olav of Norway (later King Olav V) finished first. At the presentation of the gold medals, he was the only champion who was allowed to kiss Queen Wilhelmina. The others, all being at least one step lower on the social ladder, had to bow to the queen, after which they were immediately hurried away by a footman.

Those Amsterdam waters are part of the worldwide Olympic history. In fact, their history went back even further than 1928 because, eight years earlier, a different official Olympic sailing final had been held at the same location. Antwerp was the seat of the Olympic Games then, but the event’s competition committee was unable to manage the final of the twelve-foot sloops properly. Because only two boats were competing and both came from the Netherlands, the Royal Dutch Sailing and Rowing Union was asked to take on the task. And that is, indeed, just what happened on 3 September 1920. The IJ is, therefore, an official competition location of the 1920 Antwerp Games and forever part of Belgian sports history.

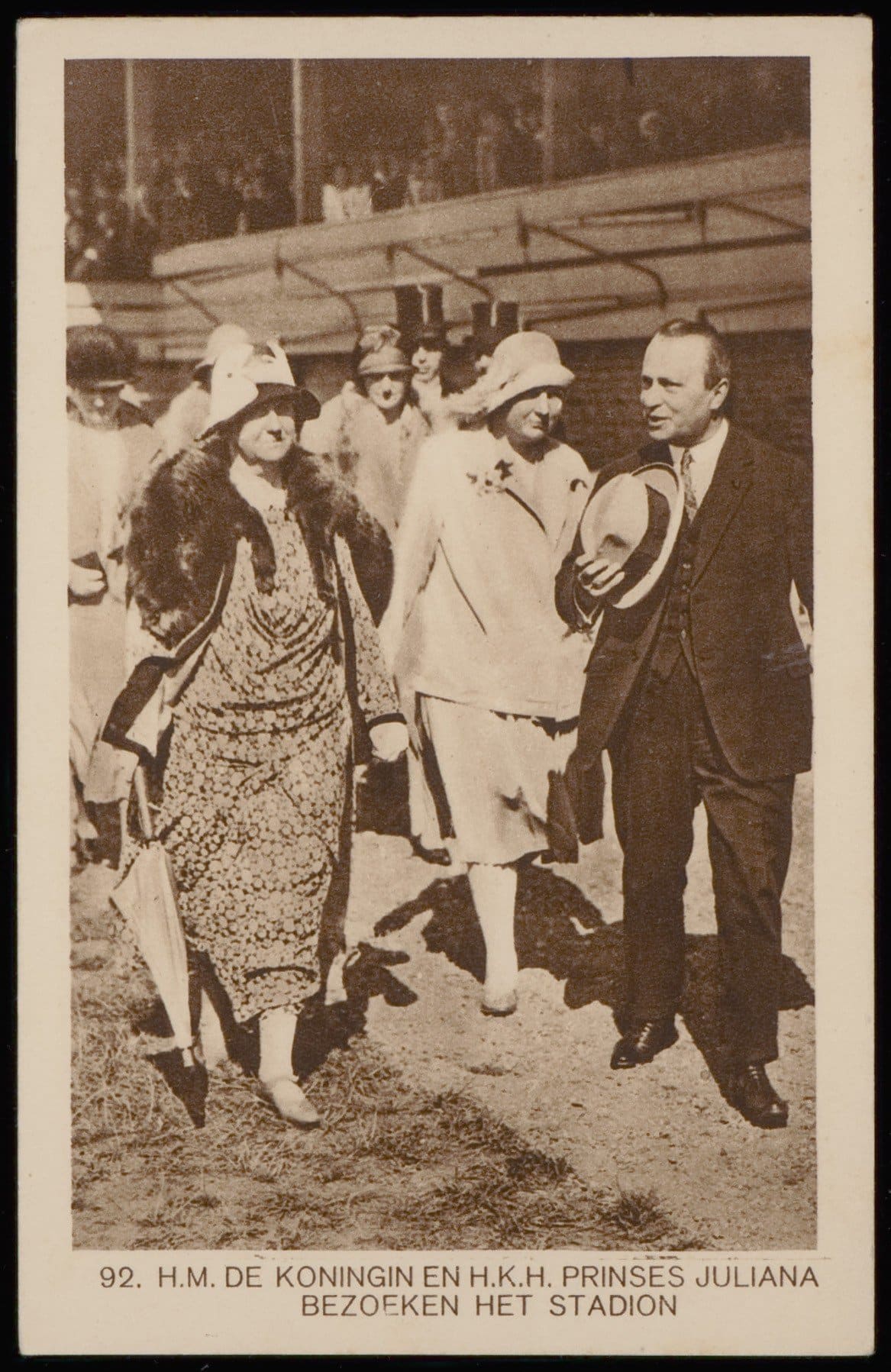

Swimming: start of the women's 200 metres

Swimming: start of the women's 200 metres© City Archives Amsterdam

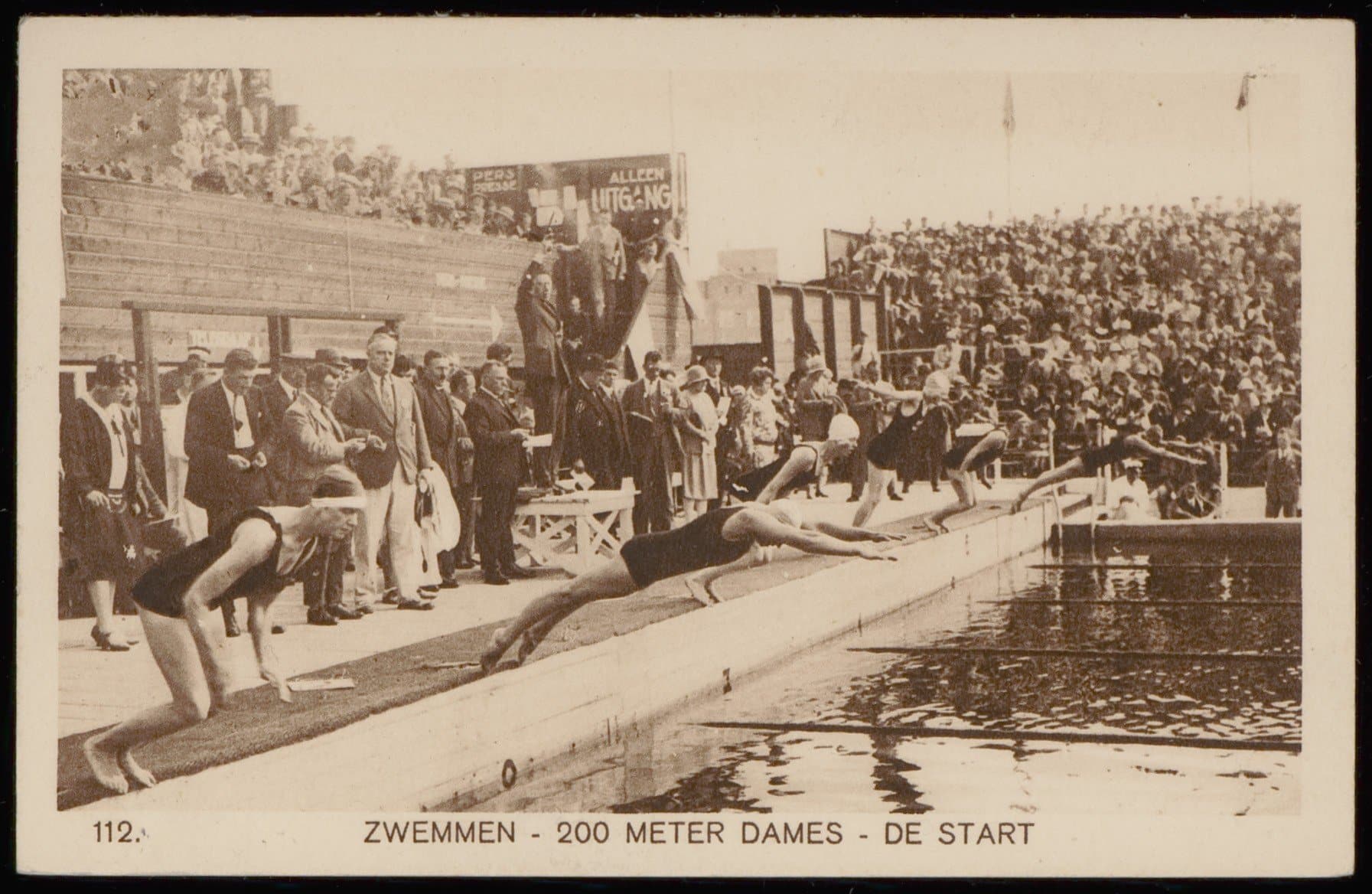

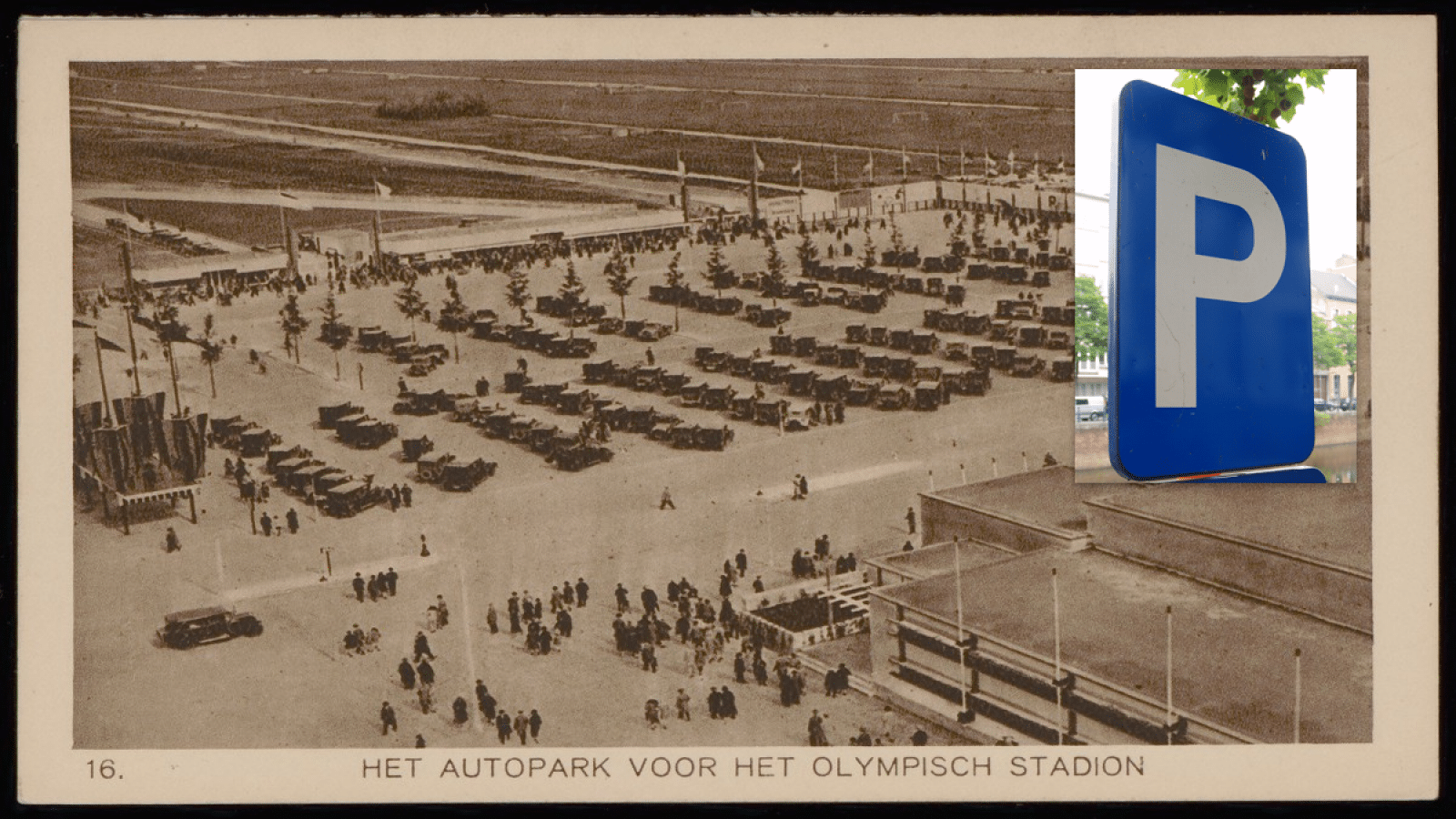

The parking sign

It is likely, though, that the most surprising tangible legacy of the 1928 Olympics can be found in your immediate vicinity – unless you live deep in a forest. In the 1920s, more and more people owned automobiles, making European cities progressively more crowded. In those early days, automobile traffic was a bit of an anarchic mess, because no international agreements about traffic signs had been made. In Amsterdam, cars were regularly a serious nuisance. Drivers parked completely randomly, causing severe disruption.

The municipality of Amsterdam was rightfully concerned about the problems that could arise during the Olympic Games if many foreigners came to the city by car. How could the city prevent two weeks of traffic chaos with cars parked everywhere?

Design with parking logo, made by the Amsterdam traffic police

Design with parking logo, made by the Amsterdam traffic police© City Archives Amsterdam

As a solution, two new signs were devised especially for Amsterdam 1928: one concerning one-way traffic and another for parking. The one-way traffic sign was supposed to prevent motorists – especially taxis – from stopping in front of the Olympic Stadium and then turning around and driving back into the city against all other traffic. The sign indicated that everyone had to drive on to return to the centre via another route. The other sign, round and blue with a white P, was placed in the square in front of the stadium. This symbolism was simple enough that everyone immediately understood it – even visitors who did not speak a word of Dutch.

On 17 May 1928, the first day of the Games, both signs were introduced with some success according to Het Vaderland, although they took some getting used to: ‘The arrows indicating one-way traffic were not yet understood by all drivers.’ Nevertheless, the Amsterdam traffic controllers survived the eventful day without major problems. ‘Considering how automobile traffic used to be, the success of the one-way signs can serve as an example to the largest world cities outside our borders.’

Car park in front of the Olympic stadium

Car park in front of the Olympic stadium© City Archives Amsterdam

The parking sign, however, was a resounding success. From Amsterdam, it started an international discussion at the League of Nations, the predecessor of the United Nations. In the late 1920s, this international organisation had established a road traffic committee with the task of introducing a worldwide standard for traffic rules and signs. They decided in 1929 that the parking sign with the letter P should be used worldwide, definitively becoming the international standard.

As a result, you don’t have to come to Amsterdam to see the heritage of the 1928 Olympic Games, whether stone or water, with your own eyes. After all, every parking sign in the world is a descendant of the original 1928 sign, including those in your own street.