Artistic Resistance as Liberation: Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s Visual Language and Image of Women

Over the past fifty years, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven has built up an oeuvre that is not only extensive, colourful and futuristic, but also layered, feminist and strongly critical of society. Assisted by modern software, her work has attained even greater subtlety in recent years.

Visual artist Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven (Antwerp, b. 1951), who started signing her work with the gender-neutral AMVK from early in her career, is a nonconformist among international artists of her generation. She has been a pioneer in computer and media art since the 1970s, long before the first PCs were in circulation, back when there were only a handful of people working on artificial intelligence.

Portrait of AMVK from the video Distort, 1997

Portrait of AMVK from the video Distort, 1997The multimedia experiment she has been conducting since 1970 has led to her own philosophy which is entirely focused on a remarkably ambitious artistic project: achieving insight into all aspects of the mind (soul) and human (female) existence.

At the end of March 2022, Van Kerckhoven received an honorary doctorate from the University of Antwerp for her “visionary scope with which the artist links art and science in her work”. In recent years large retrospective exhibitions in Belgium and abroad have followed one after another. Her mother gallery, Zeno X Gallery in Antwerp, recently tacked on a follow-up to these, during the celebration of a double anniversary: forty years of the gallery and forty years of collaboration with AMVK.

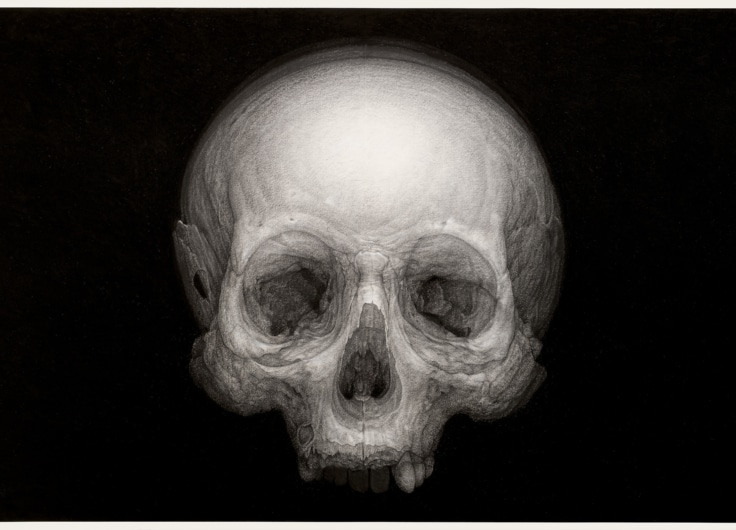

The Required Particular, 1995

The Required Particular, 1995© Peter Cox / Zeno X Gallery, Antwerpen

That led to a retrospective exhibition and a book about their fruitful collaboration. The hefty and beautifully designed publication provides a chronological visual report on her exhibitions at the gallery, supplemented with exhibitions at major international museums and institutions and reviews from international journals. It is an interesting historical document on the gradual construction of a successful career and the gallery collaboration of a female artist in an international art context which was still substantially dominated by men and market-oriented at the time. The book also offers chronological insight into the evolution of her broadly branching oeuvre and her central themes.

AMVK’s work reflects critically and pithily on human existence in today’s world, in which sex differences (gender roles), developments in technology and imaging play a dominant role.

Her non-conformist, unorthodox stance, unbridled imagination and unconventional use of different artistic disciplines and materials make her a role model for current and future generations of artists and thinkers.

Emancipatory project

Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven’s multimedia art practice has a strongly interdisciplinary stratification. Her first media were drawing and graphics, but she was quick to take up painting, writing, music, performance and installation art, video film and computer art. In drawing and graphic art in particular, her approach has been explosive and challenging, combining both analogue and digital techniques and deploying both classic and unusual synthetic materials of her time. For instance, she prefers to work with plastic, plexiglass, PVC and plastic sheeting – to her, that’s a metaphor for the manufacturability of life.

In order to put into context the ambition of her new project, let us return to the formative years of her generation. In the second half of the 1970s, Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven underwent training in graphic design for publicity drawing at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Antwerp. At the time the hippie movement was coming to an end and the stark militant countermovement, punk, had burst out. In Western Europe, the punk movement evolved in the early 1980s into diverse post-punk movements, the most important of which was the industrial movement – involving industrial music and machine art. Club Moral, the experimental noise band founded in 1981 by AMVK and her husband Danny Devos, fits into that subculture. From 1982 Club Moral published the journal Force Mental and until 1993 it organised countless events in Antwerp. The dark underground movement, which manifests itself in her early work through an unbridled urge to experiment, an unorthodox attitude and pithy humour were to play a substantial role in determining the character of her subsequent work.

Following her time at the academy, she also emerged as a thinker by studying philosophy, theology and sciences on her own initiative. She built up a gigantic library with (scholarly) books from cultural history – including works by the Marquis de Sade, Marguerite Porete, Giordano Bruno, Ignatius van Loyola, Charles Fourier, Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud – as well as pseudo-scientific books on sex and society, hidden knowledge, numerology and conspiracy theories. Through her work she engaged in dialogue with like-minded thinkers, generally combining images with text.

AMVK has also engaged in long-term collaborations with contemporary scientists, such as professor of computer sciences Luc Steels of the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, where she was artist in residence from 1981 to 1988. She jazzed up his theoretical jargon with visual and auditory interventions and computer animations.

The domestic context redrawn

AMVK’s work calls radically for discussion of imposed social conventions and linguistic, scientific and religious thought structures. She achieves this primarily by combining the archetypal feminine figure of image culture with elements of symbolism, using numbers and colours or text from scientific treatises. In doing so she subtly draws to the surface underlying gender roles and power dynamics in society. With artistic interventions, AMVK succeeds in correcting or updating the one-sided, fraught image of women and thus bringing a new sense of balance to the subject. That has a liberating effect on the (female) brain.

Her explicitly sexually charged work expresses a search for female identity, alongside the mental and physical nature of the complex, creative human being. She takes her own inner dissonance and experience as her starting point. Through her work, she goes in search of a kind of primal state, a state for which every human being strives in her view, a state in which humans live in peace with themselves and their environment.

In her work, there are many portrayals of a woman in a domestic context. Those images explore the archetypal image of the woman, who was long banished to the living room or interior in Western culture, to take on domestic tasks and care for the family. AMVK does not recognise herself at all in this image. Her own memories bring up completely different associations in a domestic context. As a child and teenager, AMVK spent a great deal of time in the castle of her hard-working parents, who ran a hotel and also a party venue. In the seclusion of the parental home, where unfamiliar guests often stayed, her thinking became radicalised and she grew socially alienated. In her idiosyncratic world, AMVK also sparks discussion on the seclusion of the domestic context as the ultimate place for safety and security, but also for dogmatic family values and gender roles.

Still from Belgian Spleen 1993: No ground left under my feet (Warding off a house-moving depression. This is an image of a house move in which melancholy mixes with feelings of liberation.

Still from Belgian Spleen 1993: No ground left under my feet (Warding off a house-moving depression. This is an image of a house move in which melancholy mixes with feelings of liberation.© AMVK / M HKA, Antwerp

In her key work Belgisch Spleen 1993: Alle grond is weg onder de voeten (Bezwering van een verhuisdepressie) (‘Belgian Spleen: No ground left under my feet (Warding off a house-moving depression’), a video-installation, you can see how she deals with the oppressive emotions she felt in her parental home. A child’s desk hangs on the wall with a chair, a child’s portrait and a video showing the legs of a person restlessly walking back and forth. These are images of a house move in which melancholy mixes with feelings of liberation.

It’s no wonder that her studio and living space in her middle-class house, in contrast to the interior of her parents’ house, becomes a kind of sanctuary. There she practises consciousness expansion and brings the outside world in through a variety of channels (books, videos, internet). Alongside the pencil, which directly registers the stream of her thoughts, the computer offers the most important escape route. Using the two enables her to link different realities, thus expanding her world. New software (virtual reality and augmented reality) also gives her wings: she can open up different perspectives with it, and expand her consciousness. It is a remedy for getting stuck or stagnating.

All her works can also be viewed as a battle for liberation. They originate in a deep longing to shape her own life and not to subordinate herself to any restrictive system.

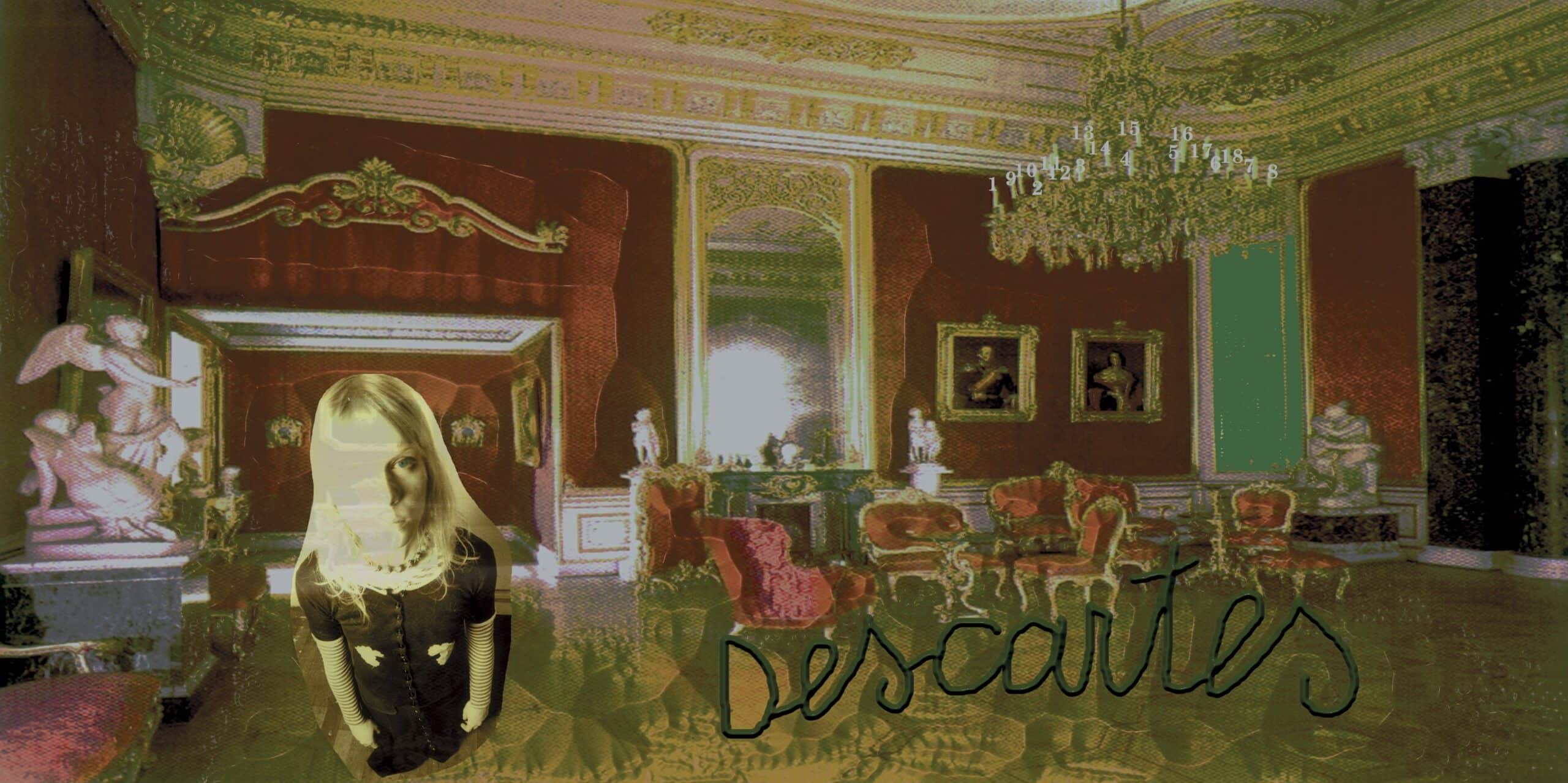

Sliding dimensions

Since the 1990s, collage and montage have been AMVK’s main tools. She creates interiors on the computer. An example is the four-part series Filosofische ruimtes (‘Philosophical rooms’, 1999), which consists of digital photo collages in which she repeatedly combines a portrait of herself with the written name of an enlightenment philosopher (Descartes, Spinoza…). This is done against the background of a deftly produced interior from a Potsdam palace. The self-portrait of AMVK as an academy student invokes the archetypal image of wild feminine nature, the indomitable female. That image contrasts starkly with the rational framework of thought invoked by Descartes. This image incisively and ironically exposes the compromising position of the free-thinking woman in the time of the Enlightenment, when the scientific and intellectual approach became the new, dominant thought pattern in the West.

Image from the Philosophical rooms series, that incisively and ironically exposes the compromising position of the free-thinking woman in the time of the Enlightenment.

Image from the Philosophical rooms series, that incisively and ironically exposes the compromising position of the free-thinking woman in the time of the Enlightenment.© AMVK / M HKA, Antwerp

In the computer animation film A-X+B=12 (2020), AMVK has woven together 76 animated drawings of interiors by means of intensive digital processing. The drawings more or less span the entire active life of the artist, from 1977 to 2020. It is an evocative, rhythmic work which sweeps the viewer along in a long trip of sliding interiors and temporal dimensions, in which bodies, objects and abstractions interact with one another. A-X + B=12 is a Gesamtkunstwerk which condenses all the art forms AMVK practises, including her musical explorations of boundaries, and which encompasses all temporal dimensions (A = the past, X = the present, B = the future).

On the structure of the film, AMVK says, “The drawings have been divided into twelve focal points which describe the journey of a spirit becoming a human being.”

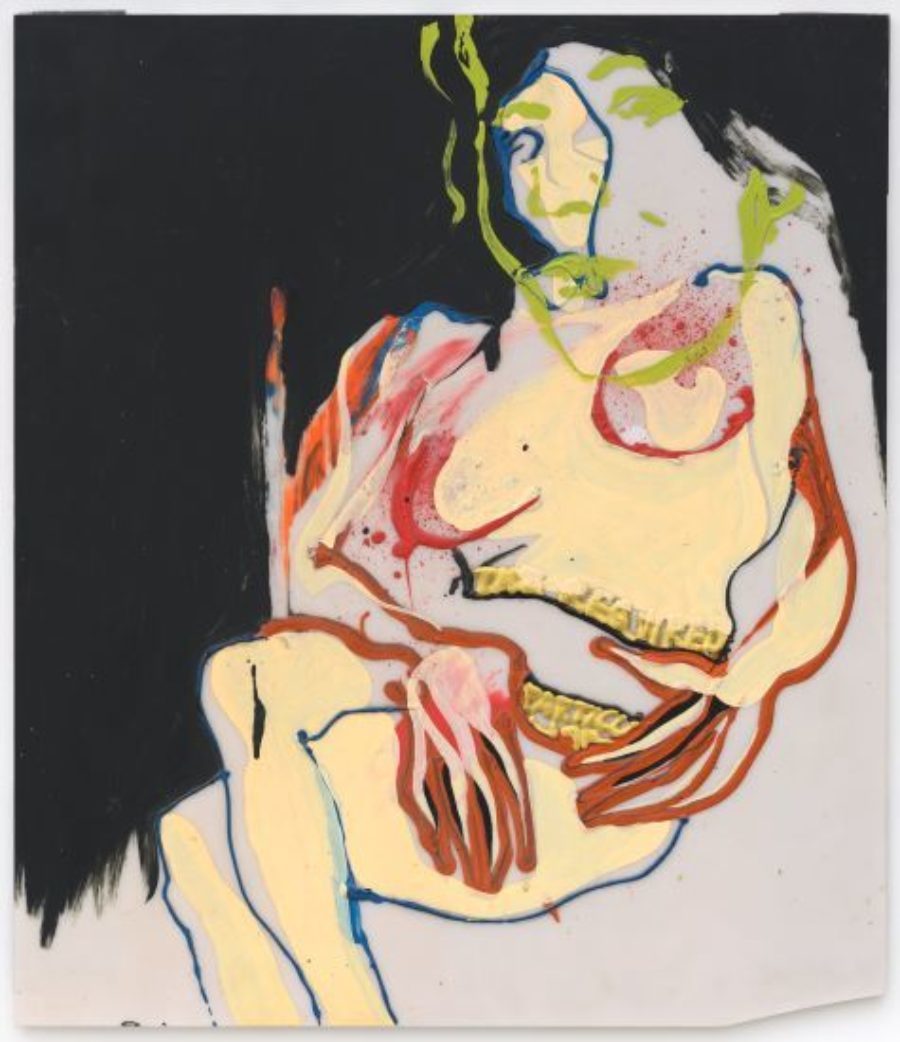

Powerful, vibrant nude

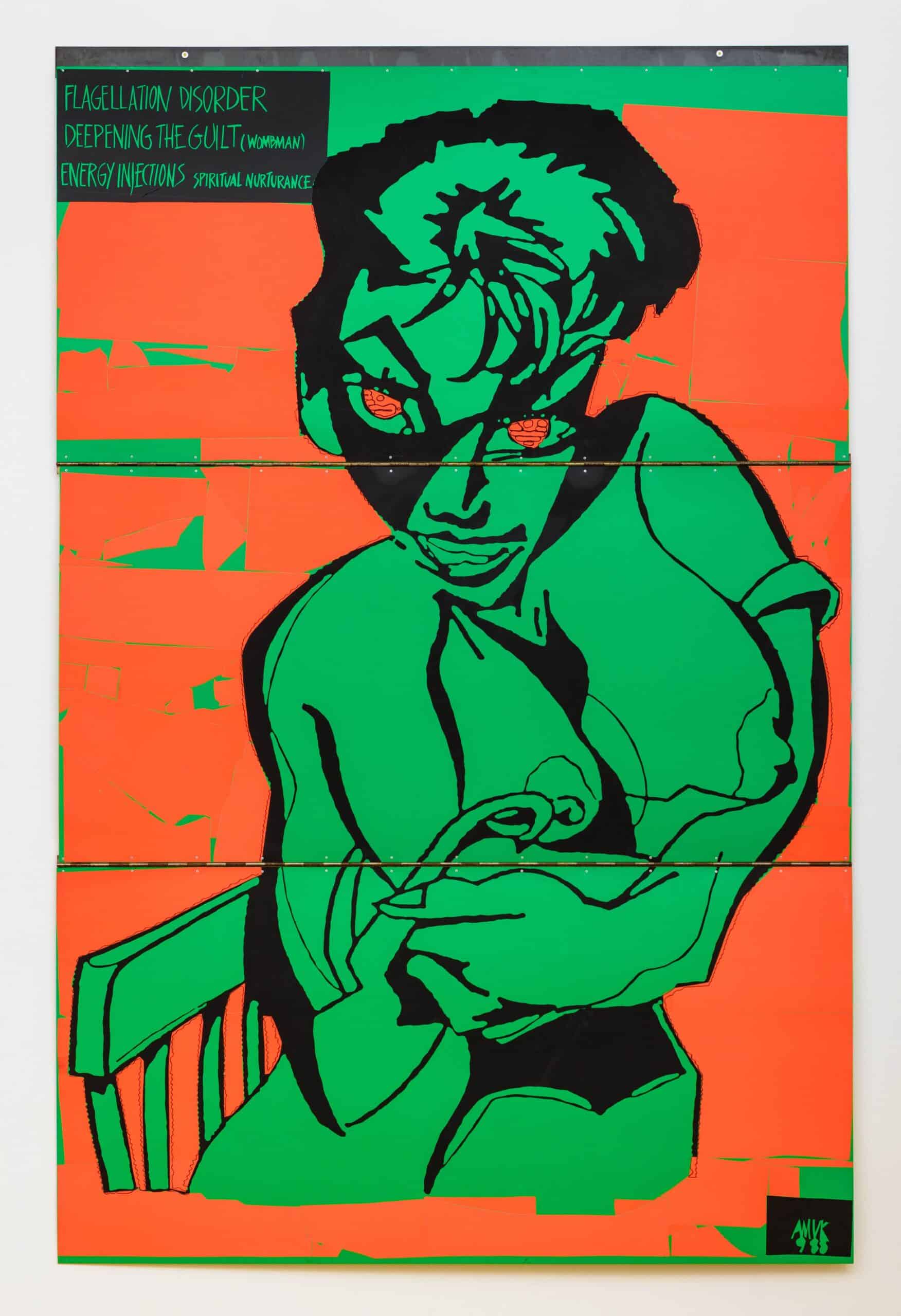

Naked or partially clothed women form a recurring motif in AMVK’s work. The graphic design language refers to popular image culture (comic strips, magazines featuring naked images…). In doing so her image of women differs substantially from that of the traditional nude of Western art. There is no refined, sensual aesthetic but rather a powerful, vibrant nude expressing zest for life and fertility. This image of women already had a strong presence in her early work from the 1980s, in which a raw, expressive, futuristic machine-aesthetic gains the upper hand. An example of this is the monumental silkscreen paint collage on PVC, Atman/Wombman (1988), a cartoon heroine with a substantial bust in bright green, which emanates desire and superpowers. She is self-confident and seductive, simultaneously demonic and mysterious. The sharp industrial colour contrasts (bright green against fluorescent orange) and the remoteness of the materials (synthetic and metallic) enhance the machine aesthetic.

Atman/Wombman, 1988. She is self-confident and seductive, simultaneously demonic and mysterious.

Atman/Wombman, 1988. She is self-confident and seductive, simultaneously demonic and mysterious.© Peter Cox / Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Throughout her academy time, AMVK drew (half)naked women as a reaction to the hypocritical middle-class environment in which she grew up. In a database, she kept pin-ups out of magazines featuring naked images from before the sexual revolution. She likes to work with pin-ups from that period due to their underlying meanings: they speak volumes about gender roles and men’s secret desires. For decades AMVK has been working these pin-ups into images and texts from other sources.

In 1998 she adopted the alter ego HeadNurse, a head nurse who first cares for herself and then turns to the treatment of society by means of her art. As HeadNurse she directed the HeadNurse project (1995-2005), a large-scale project with the themes of sex differences, technology and imaging at the centre. There she began to process pin-ups in a more systematic fashion in consecutive parts, with titles such as Morele herbewapening (‘Moral rearmament’), HeadNurse and How reliable is the brain?

Throughout her academy time, AMVK drew (half)naked women as a reaction to the hypocritical middle-class environment in which she grew up

In Morele herbewapening she pairs 96 existing images of women from her database with 96 concepts from the world of artificial intelligence in the domains of internal self-organisation, thermodynamics and knowledge representation. Each woman is a new-meaning machine in motion. The possibilities offered by the computer and the internet enable her to create and mix different (virtual) realities. She creates systems, nestles within them and re-emerges. There are no fixed compositions, only flexible structures.

How does she get those flexible structures to function in an exhibition? It will come as no surprise that she has to fundamentally transform the existing architecture of the museum, as in her head there are no static formations, only dynamic movement. Around the room, she therefore designs her own exhibition architecture, in the case of HeadNurse she adopts a flexible slat structure with metal panels. Images of women and texts are attached to it with magnets. They can change place as easily as images in our heads can.

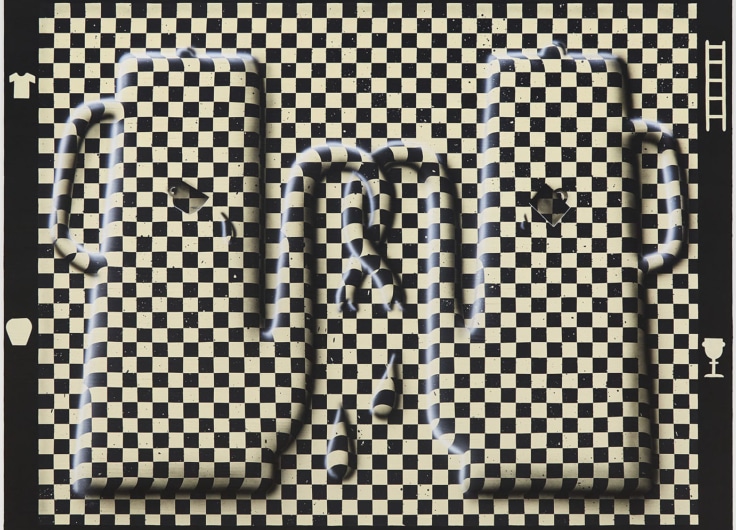

Premiere Celu Garnitures, 2021

Premiere Celu Garnitures, 2021© Peter Cox / Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Distorted image of women corrected

Over the last two decades, AMVK has made many more photo collages of pin-ups. She started on the most recent cycle of women in 2017. For this project, she starts out again with scanned pages out of magazines featuring naked images, which she then processes digitally. She doubles up or mirrors female protagonists and adds elements related to what interests her at the time. Once again, issues such as abuse of power, seduction and manipulation come to the fore. It is also noticeable that besides the familiar graphic techniques such as screen printing she has become more skilled with computer software and is again working with a rich range of materials, achieving greater stratification and subtlety with her work.

Dudoute Toaster Absolu derives its title from word strings generated by algorithms.

Dudoute Toaster Absolu derives its title from word strings generated by algorithms.© Peter Cox / Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Since early 2021 she has also worked with word strings she received out of the blue from her email server. The words were placed in sets of three, allocated by an algorithm, and she has used the evocative combinations as titles of recent works, such as Premiere Celu Garnitures (2021) and Lacaztro Onnet Copeau (2021). According to the gallery text, the enigmatic title Placenta Saturnine Bercail from the recent solo exhibition at Zeno X also came from that series. Nevertheless, that also has a specific significance for her. Placenta

stands for “All the work I make comes from my uterus.” Saturnine: “Saturn is the planet of the artist.” And Bercail: “An Old French word for a stall where animals are kept. That’s how I see the security that being associated with a mother gallery gives me.”

In the solo exhibition, the gallery particularly emphasised AMVK’s core business: the complex image of women. The artist has now produced hundreds of complex female figures as a counterweight to the distorted image of women from the popular image culture surrounding us. AMVK’s special oeuvre can be succinctly described as a homage to the irrepressible nature of women, which is simultaneously resolute and wise, sacred, sensual and demonic, but above all exhibits great creative force.

Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven-Zeno X Gallery – A Long-Standing Collaboration, Hannibal, Veurne, 2022, 256 pp.