An Empty European Mind. ‘Grand Hotel Europa’ by Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer

A writer by the name of Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer leaves Venice and moves into the illustrious but decaying Grand Hotel Europa, to think about his broken relationship with art historian Clio. In the hotel, he reconstructs exactly what went wrong with Clio and befriends the eccentric hotel staff and guests along the way. Grand Hotel Europa is Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer’s much-acclaimed novel on the old continent, European identity, nostalgia and the end of an era. The bestseller is now available in English.

He can’t do it. Tradition weighs too heavily on his shoulders. He doesn’t have a clue how to say something that hasn’t already been said, to create something that hasn’t already been created. The filmmaker, who was supposed to make a documentary with the writer Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer about the significance of tourism in Europe, throws in the towel in Grand Hotel Europa. He says himself that he has lost the naïveté necessary ‘to believe in the illusion that he could add anything worthwhile to all the artworks that already exist.’

Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer

Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer© Stephan Vanfleteren

But Pfeijffer – or at least the character in the novel who bears the same name as the author – does not let himself be stifled by the suffocating abundance of the past. He is well aware of it, ‘Living is reliving. Nothing can ever be new on an old continent.’ Yet he does not allow himself to be disheartened by it either. In the Palazzo Grassi in Venice, he and his beloved Clio visit an exhibition of work by the megalomaniac British artist Damien Hirst. ‘That’s how I must write, I thought, in the spirit of this show of strength, this munificence, this pleasure in the adventure.’ His desire was to ‘encompass the times I was living in in marble sentences’ and to ‘astonish’.

It looks very much as if this is the author’s own intention, too. He wanted Grand Hotel Europa to be a philosophical novel encapsulating the spirit of Europe as it is now, a novel to rival Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain (Der Zauberberg, 1924). And to commit a love story to paper with the sex steaming more fragrantly from the page than from Jan Wolker’s Turkish Delight (Turks fruit, 1969).

Pfeijffer wanted to write a philosophical novel encapsulating the spirit of Europe as it is now

Praised be his courage. But, of course, his daring also compels readers to ask whether Pfeijffer has achieved his ambitions.

The sanatorium in the novel is the Grand Hotel Europa, a hotel where Europe’s beau monde used to stay, and the staff carries on repeating the rituals of days gone by for its regular guests. There Pfeijffer – the character in the novel, that is, has dinner with other regular guests, like Patelski, an elderly scholar. ‘This barbarian invasion of Europe’, says the latter, when Pfeijffer tells him that he intends to write a book about tourism, ‘is seen as a revenue model and actually stimulated, while in fact, it’s a threat. This forms an interesting parallel with the supposed African invasion of Europe, which is presented as a threat while it offers us a future.’

Patelski’s words might have come from the mouth of the main character Pfeijffer or equally from the newspaper columnist Pfeijffer. Personally, I prefer the intellectual sparring matches in The Magic Mountain between the progressive ideologist Settembrini, with his passionate belief in reason, and the Jesuit Naphta, for whom to be human means to be ill. Patelski and Pfeijffer mainly try to curry favour with each other, confirming how absolutely right they each are. The reflections of the two characters can be summarised on an A4. The Occident – Europe – is tired, has lost its drive for innovation, lives only in the past, it risks becoming one big Venice, where life is just play-acted and the plague that is tourism wreaks havoc.

In his graphic descriptions of steamy sex, Pfeijffer is a master of sensationalism

Of course, Pfeijffer knows how to present all this in an extremely entertaining and clever way. Take the chapter in which his alter ego goes with documentary-maker Marco to visit two travel-mad couples in Giethoorn. They are scathing about the tourists that spoil this waterside village in the province of Overijssel. Yet they see themselves as explorers. Competing with each other for the most authentic experience, one of the couples tells how they witnessed a ritual honour rape, or panchayat, whereby the rapist’s sister was publicly raped by the victim’s brother. In rousing prose Pfeijffer describes the derailment of the travellers, who reserve the right to a grandstand view, in a desire to be able to recount – or perhaps invent – the most powerful story. But, with all the stylistic show of power, it gets so out of hand that the characters lose any credibility and become vehicles for the idea that homo touristicus is just like anyone else, but thinks he is unique and superior to the masses.

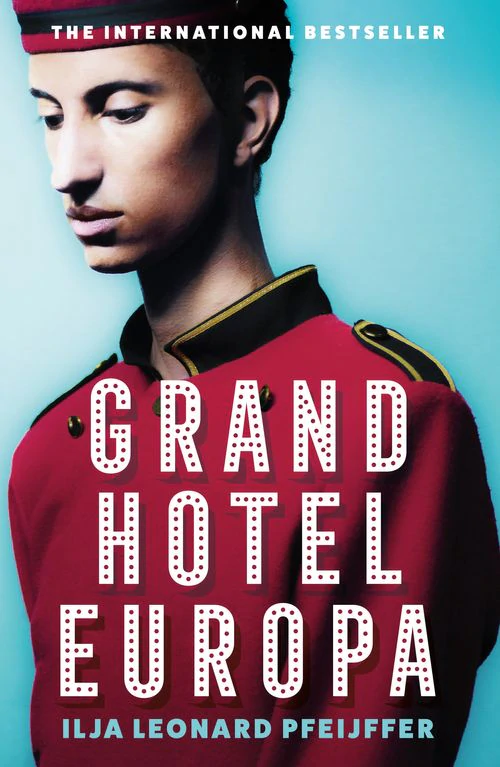

UK edition of Grand Hotel Europa

UK edition of Grand Hotel EuropaEven in his graphic descriptions of steamy sex, Pfeijffer is a master of sensationalism. It is difficult to erase from your mind the scene in which an abused American teenager manages to override the reservations of Pfeijffer’s alter ego and turn his European head with her ‘pussy fur porn shoes’ and ‘bombastic breasts’. Afterwards, of course, after his ‘memorable ejaculation inside the body of a child’, he regrets it, ‘At the very first trial, I’d whisked off my theatrical disguise faster than she could take off her panties’. Yet while all the ingredients are there for a harrowing drama, you are left mainly with the feeling of having watched a juicy play that, while it did not bore you for a second, left you totally unmoved.

The chapters in which Pfeijffer looks back at the blossoming and wilting of his affair with Clio fall into the amusing and exuberant category. Here, too, the sex leaves little to the imagination: ‘To remove any doubts as to her intentions, she grabbed for my cock behind her back with her other hand and pulled it without detour toward the entrance to her cunt.’ The scenes in which the lovers’ row are equally explosive. But if you are looking for passages that explore the breathtaking depth of their love or make you feel the pain of their break-up, you will be disappointed.

US edition of Grand Hotel Europa

US edition of Grand Hotel EuropaThe Grand Hotel Europa where, according to Pfeijffer, he remembers Clio with anguish, has fallen into the hands of Mr. Wang, who is converting the hotel into ‘a resort that will be recognized and appreciated by future Chinese guests as typically European’. He replaces the portrait of Niccolò Paganini, painted while the violin virtuoso was staying there, with a romantic poster of Paris, and he converts the late-nineteenth-century Chinese room into an English pub. The soul of the hotel evaporates, becoming an ingenious form of imitation.

Perhaps it is a shot into an open goal, but it is tempting to draw the same conclusion about the book. The enormous narrative pleasure and the outward show cannot make up for the fact that the novel harbours no real emotional or intellectual tension.