Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of Anna Asbury. Recent (co-)translations by her include Your Story, My Story by Connie Palmen and My Name is Selma by Selma van de Perre.

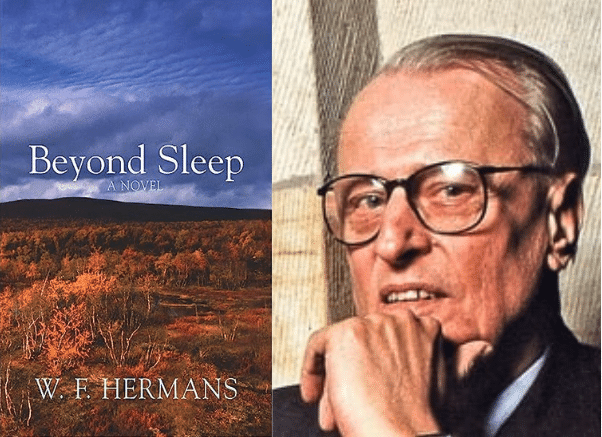

Must-read: 'Beyond Sleep' by Willem Frederik Hermans

Beyond Sleep by Willem Frederik Hermans is a literary classic, published in 1966 by one of the ‘big three’ post-war Dutch authors, and eloquently translated by Ina Rilke in 2006. The main protagonist, Alfred Issendorf, embarks on an expedition in the north of Norway for his PhD in geology. He stops off in Oslo to collect aerial photos essential to his work from one Professor Nummedal, a contact of his supervisor, but his quest turns out to be an exasperating wild goose chase and he is compelled to set off without the materials. He proceeds to meet with other researchers to embark on a difficult hike into the wilderness in search of the terrain he wishes to study, finding himself woefully unprepared for the physical demands of the expedition. Eventually he becomes separated from his companions and eventually finds Arne, the only one to have shown him any sympathy, dead at the bottom of a ravine.

I first read the book almost two decades ago and have returned to it many times, sharing it with friends and my local book club. The raw anxiety of the main protagonist, combined with evocative descriptions of the Scandinavian scenery and pervasive daylight are particularly striking. The beautifully constructed prose and thought-provoking observations of character, as well as academic and literary life, make this a compelling read. Hermans is known along with Harry Mulisch and Gerard Reve as one of the big three post-war Dutch authors and had a reputation for being a cantankerous character. The Darkroom of Damocles, also translated by Ina Rilke, is probably his most famous novel, while most of the titles from his extensive and varied body of work remain to be translated.

Willem Frederik Hermans, Beyond Sleep, translated from the Dutch by Ina Rilke, Harvill Secker, 2006, 320 pages

To be translated: 'Bult' by Marieke de Maré

One of the books I would love to see translated is Bult (Bump), a whimsical, poetic and philosophical novella by Flemish author Marieke de Maré. The three main characters remain unnamed throughout and are consistently referred to as ‘the young woman’, ‘the old woman’ and ‘the tall slim man’. The young woman comes to live on the hill named Bump and gradually forms a warm friendship with the old woman and an awkward romance with the tall slim man. Each of the characters is grappling with loss, their interactions gradually revealing more about their emotional lives. De Maré is playful with the layout of her book: the text is set out sparsely on the pages, some of which are crossed with bumpy lines, while liberal use of line breaks indicates departures into poetry with even the occasional rhyming couplet. Several motifs recur through the book, including lumps and bumps, marbles, trees, climbing, falling and flying, and the death of the sun. The gentle humour of the prose balances out the poignant scenes of loss, making this a thoughtful, calming read, in some ways reminiscent of Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist. I hope to be able to share it with non-Dutch readers someday soon.

Marieke de Maré, Bult, Uitgeverij Vrijdag, 2020, 120 pages

Read our review of Bult.

Excerpt from ‘Bult’, translated by Anna Asbury

Bump would have liked to have been a symmetrical, domed rise in the landscape.

But it wasn’t.

Bump was an irregular bump.

With one single gentle slope.

Two women and one tall slim man.

The three each owned a small house on the gentle slope of Bump.

One woman was older and collected marbles.

The other was younger and collected nothing.

The women’s gardens lay side by side, a green wire in between.

When the young woman came to live on Bump, she dropped by her neighbour one morning to ask about planting a hedge between their gardens. On the border, not beside.

‘A hedge in common I mean.’

The older woman laughed out loud and invited the younger in to inspect her marble collection, but the younger woman really wanted an answer as soon as possible to the question of the common hedge.

‘I have no problem with a common hedge,’ said the older woman pulling a twister from her apron. ‘Ever held a genuine twister in your hand?’

That was a beginning.

Across the street, opposite the women’s houses, lived the tall slim man. He had a small Phalène, which emphasised his long legs.

In the first weeks the young woman lived there, she saw the tall slim man walk down and up Bump with his dog every evening. From the first day the young woman felt the man didn’t wholeheartedly love the dog.

‘Good evening,’ she said when she saw them.

‘Good evening Miss,’ he said.

As always the Phalène hung its head.

—

Before the young woman lived on Bump the old woman and the tall slim man had been on neighbourly terms.

The old woman occasionally invited the tall slim man round, but he never accepted. She’d asked him

once in a while if he’d like to see her marble collection, but he always gave unusual excuses. ‘I’m looking for the right sandpaper for my cabinet’ or ‘there’s a guinea-fowl on the kitchen counter’ or ‘I need to unpack my silk paper.’

After a while the old woman decided to leave a slice of cake on a plate, covered in transparent cling film, at his door, with a card attached: For you.

He always politely ate the cake, returned the plate and said, ‘Thanks.’

Thus far. Never further.

The young woman might change life on the gentle slope of Bump.

But that wasn’t her plan.

She had just one plan,

her plan for a hedge in common.

(…)

The young woman was gentle.

Fragile and frail and pale,

unable to be abrasive.

She was goodness through and through.

Had never been rough or harsh.

Only her hands were calloused,

as she went climbing every Monday.

Since the age of five she’d climbed all that beckoned,

anything to avoid remaining grounded.

She’d been a pendulous child.

So her father signed her up for a climbing club.

‘Club seeks climbers’, he was sold.

Not for the climbing.

For the falling.

How many times had he cried, ‘Fall!’

When she was on the point of reaching the top, he bellowed from beneath, ‘Now fall!’

And she did.

She fell with abandon.

She fell spellbound.