Annabelle Binnerts Displays Text Where You’re Expecting an Image

Annabelle Binnerts sees the possibilities of ambiguity. The young Dutch artist has built up a diverse oeuvre in which language is increasingly prominent both as a theme and as a medium. She has a preference for features such as words, shadows and maps, more to function as placeholders than as the items themselves.

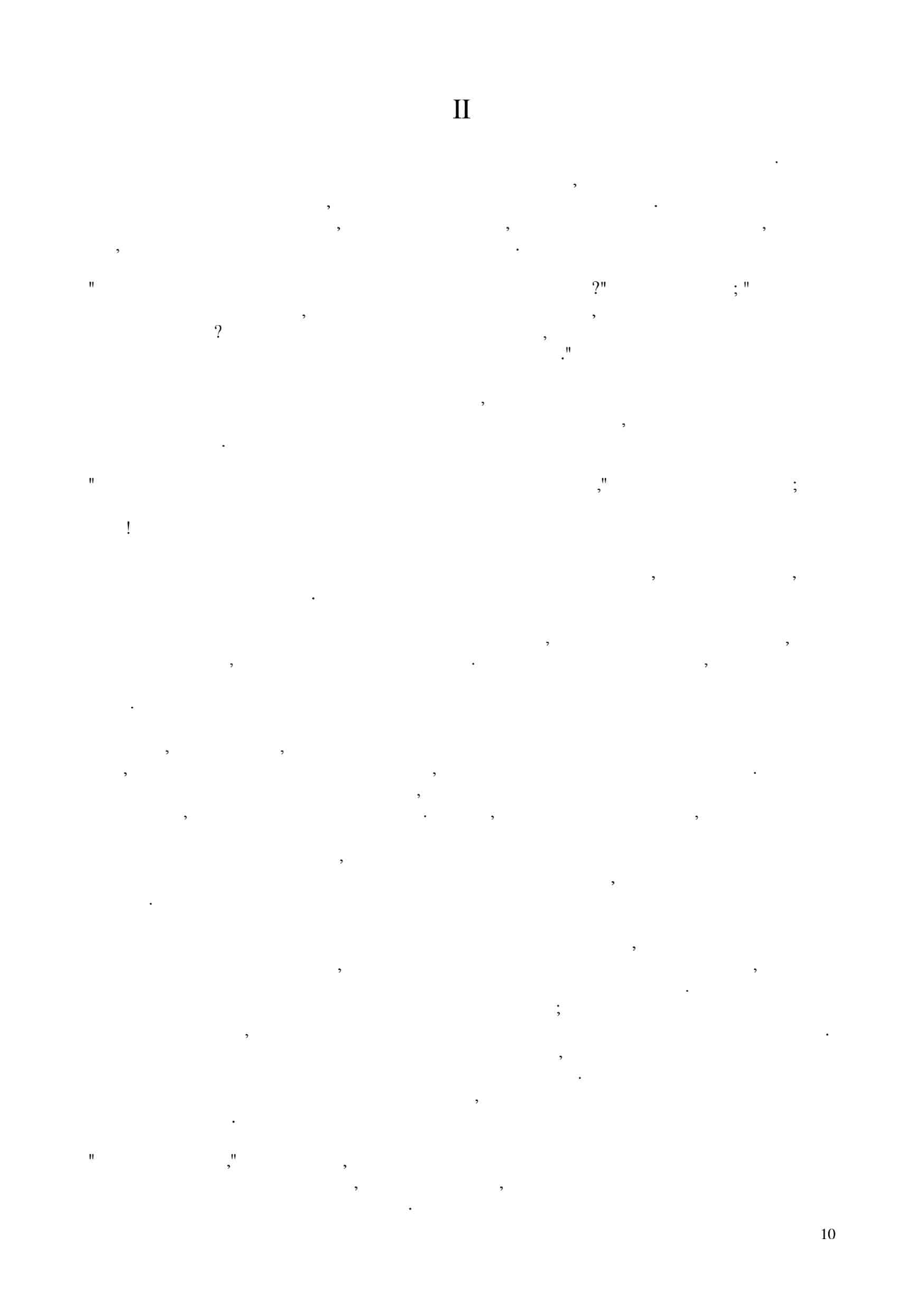

Page 10 of No Title

Page 10 of No TitleIn 2015 Annabelle Binnerts (b. 1995) made a book, twenty-eight pages long, but with no words. Each page had only a page number and punctuation marks on it: a sort of constellation of commas and stops. Sometimes there was a very vague suggestion of a story: dialogues marked with quotes; question marks and a little further on an exclamation mark. Binnerts referred to the rest as the silences in the text. The whole thing looks like an extreme attempt at erasing; the book is even titled No title.

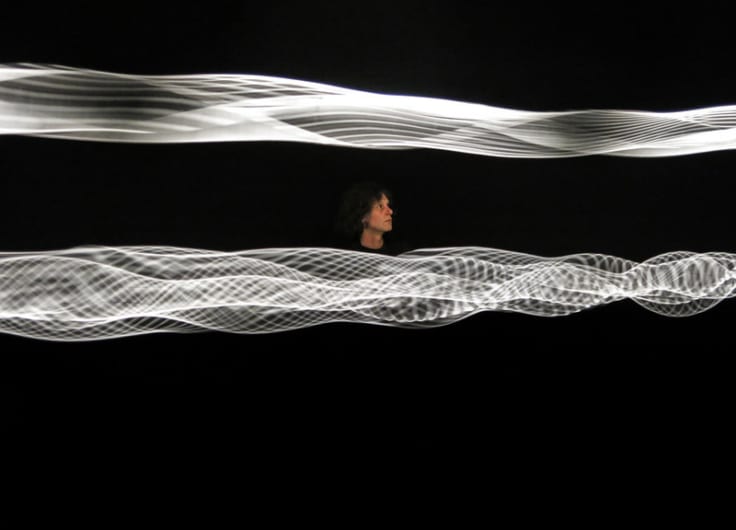

In subsequent years several works of art and projects followed in which silence and absence played a key role. Binnerts even made a series of videos under the title Silence videos (2016). She exhibited them during the short intervals of a performance evening, between the applause at the end of one act and that welcoming the next. They were projected onto a piece of white canvas that also played a role in the videos themselves: it kept on bulging in the wind.

Still from a Silence Video

Still from a Silence VideoThose were small, insignificant events which barely made a sound, but due to the camera, they still expanded to become something that briefly dominated the screen. Then the canvas featured in the film stopped flapping and the canvas on which the film was projected vanished from the stage. Both objects differed radically in function and in the reality in which they were situated, but at the same time there was a resemblance between them, tempting viewers to see them as the same object. That gave it an indeterminate feel: where precisely does the video end and reality begin?

It doesn't say what it says

That doubt is somewhat reminiscent of René Magritte’s The Treachery of Images, better known as ‘This is not a pipe’. The painting became a world-famous reminder that an image is not the object itself. However, that depends on the question of which reality you place that pipe in: outside the canvas, it’s clearly not a pipe, but on canvas it is. Such ambiguity plays an important role in Binnerts’ work. She reveals the difficulties of it but focuses more on the possibilities. In daily life, an ambiguous formulation can cause lack of clarity and even miscommunication, but in a poem, for example, space is created for several layers of meaning. Certainly, in modern and contemporary poetry it’s the rule rather than the exception that you don’t take the text (purely) literally: ‘Have a read, it doesn’t say what it says,’ as Martinus Nijhoff’s famous line goes. Because form and content – or external and internal – are not in one-to-one correspondence, space arises for additional meaning.

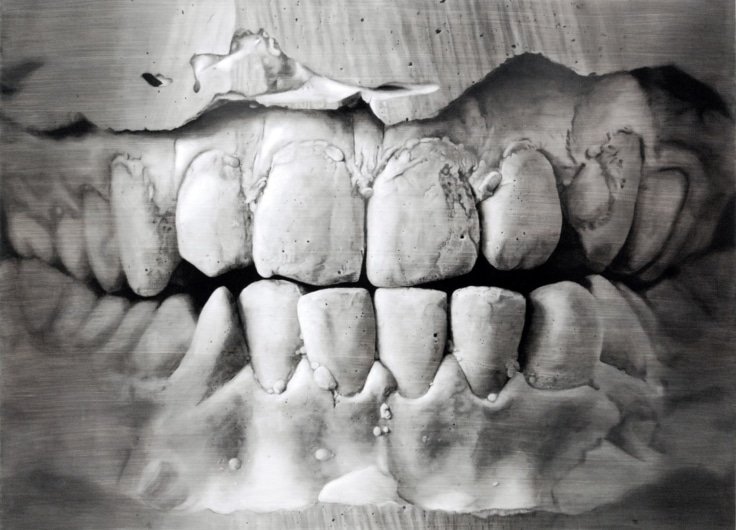

Annabelle Binnerts

Annabelle Binnerts© Pauline Niks

When Binnerts applied to art academy, it was to the department of Image and Language. As the name suggests, students receive tuition not only in painting, drawing and photography, for example, but also in creative writing. Image, language and the relationship between them all remain important throughout the course, but the balance or focus may vary from one student to another. Binnerts recalls that one of the students in her year graduated with a novel.

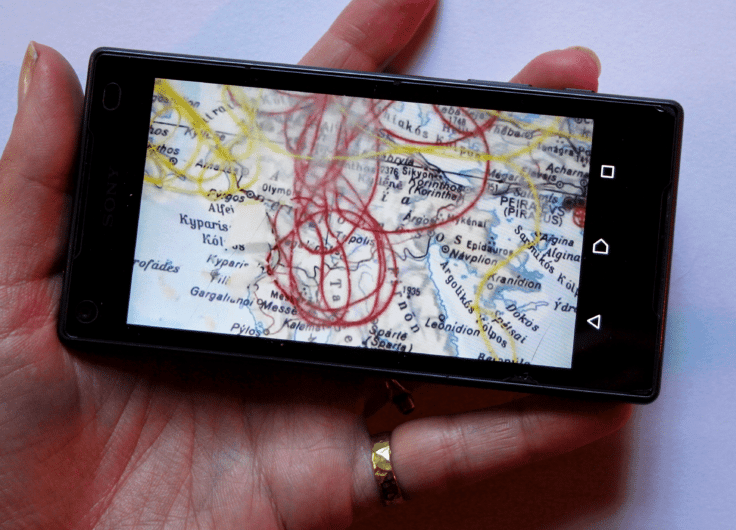

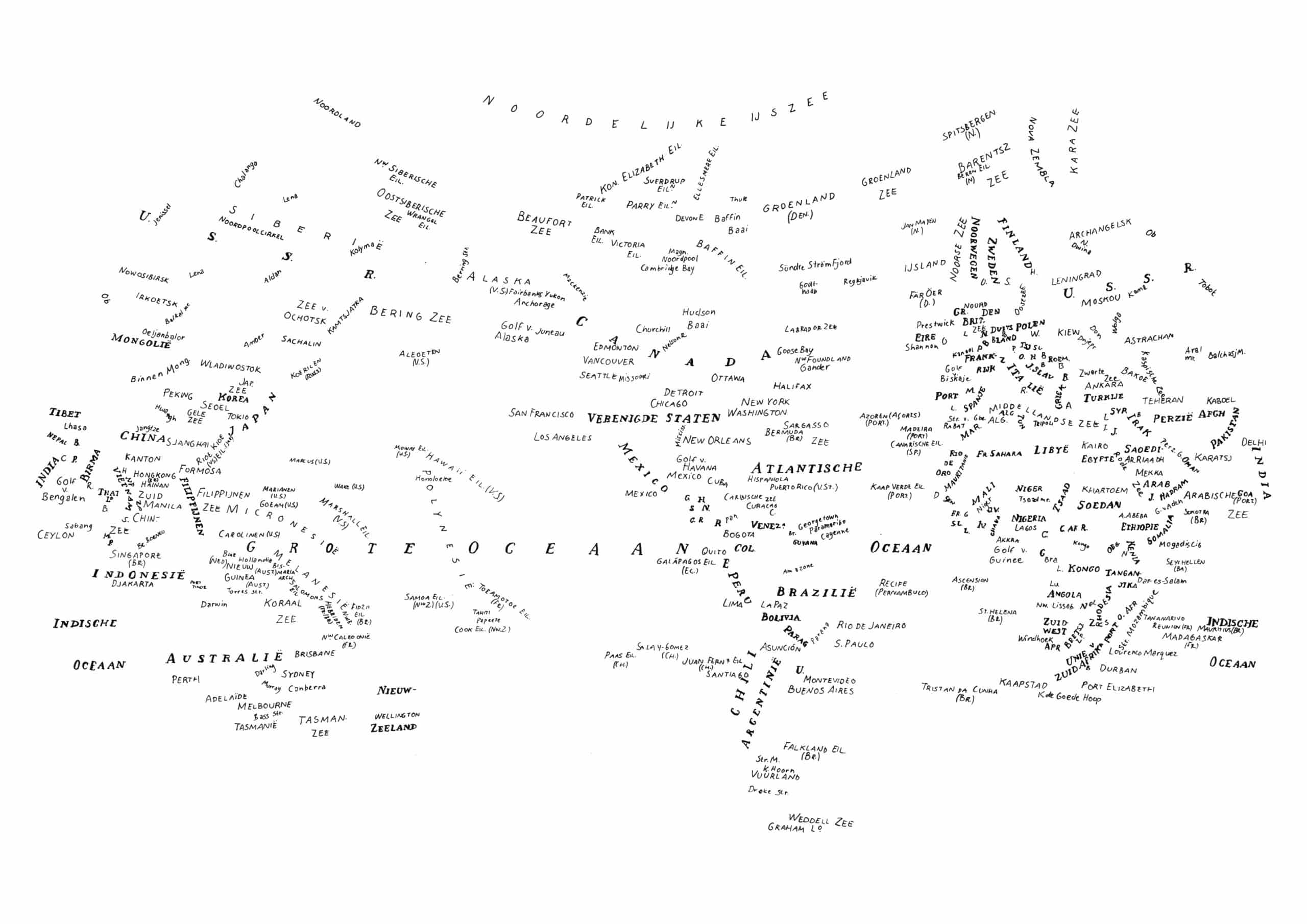

She herself did a project in her final year which might be subtitled ‘Image or Language’: Atlas (2017). She drew maps from an old atlas by hand, imitating them with one important difference: only the names remained. These adjusted maps are reminiscent of No title, but it’s hard to say which of the two pieces involves the greatest deletion. In Atlas, Binnerts Is perhaps playing an even further-reaching game with presence and absence. Maps are already partial, rather abstract versions of reality; substitutes or placeholders for it. A name is more abstract still: an agreement to refer to a particular country, city or stretch of water with that word.

The result of Binnerts’ intervention is strongly evocative of the visual poetry of Paul van Ostaijen: letters demanding attention because they are distributed in curves and squiggles over the page – but mainly letters, no places. They’re the substitutes for the substitutes, but that’s not to say that they’re absent themselves. Have a read, it says what it says and yet it doesn’t. Trying to comprehend that creates a pleasant sensation of short circuit.

World map

World mapThe strange tension between presence and absence comes to the fore more often in Binnerts’ work. Take for instance the exhibition A Short Ride in a Fast Machine, which she put on with two artist friends – Bart Lunenburg and Caz Egelie – and which was on show at Moira (Utrecht, January 2019). The exhibition was a retrospective of a fictional artist consistently referred to as The Artist – who notably otherwise remained nameless. It became clear, however, that this was no mystification to be maintained at any cost. For instance, there were photos – based on the cliché image of an artist – of Binnerts, Lunenburg and Egelie, but always with the proviso ‘as an artist’ (my italics). Had the fictional artist replaced the genuine artist, was it precisely the other way around or were they constantly switching back and forth?

A Short Ride in a Fast Machine

A Short Ride in a Fast MachineClosed books

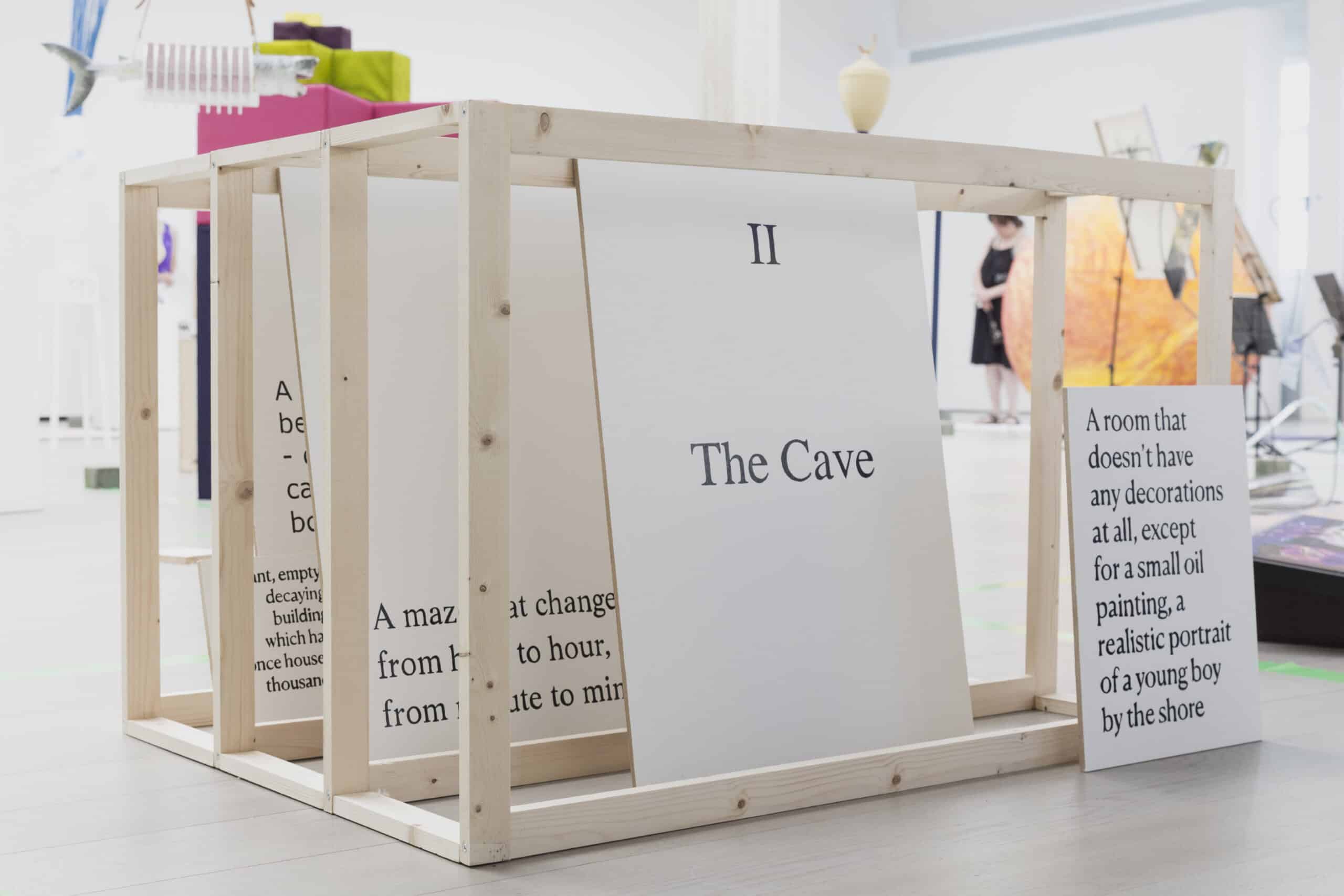

In recent years Binnerts’ attention has primarily moved in a linguistic direction. She has established an interesting, elusive way of uniting text and image, placing painted or printed words on objects which she exhibits. There is a difference between opening a book oneself at home, for instance, because you feel like it, she notes or going to an exhibition where you’re more or less forced to read. You see a text in a place where you would expect an image. You might well feel you’ve been mis-sold, she jokes, but she has a good point: exhibited texts demand a different approach.

Reads Like a Book

Reads Like a BookOne of these ‘textworks’ is Reads Like a Book (2018), consisting of a series of panels on which she has painted the pieces of text; if you look carefully you see errors – and hence the human hand – in what otherwise would have appeared to be printed letters. The texts are chapter titles such as ‘The Cave’ and ‘The Island’, and descriptions of (sometimes literally impossible) spaces such as a swimming pool so deep you can’t see the bottom or an alley with a dead end in both directions. They’re sentences and phrases isolated from books which Binnerts herself read; you could call them a close-up of language. Of course, the descriptive texts aren’t the spaces themselves; those words are not even directly visualised. However, that’s not problematic. There may be no one-to-one correspondence, but that gives your imagination free rein. Binnerts thus casts doubt on the cliché that an image says more than a thousand words.

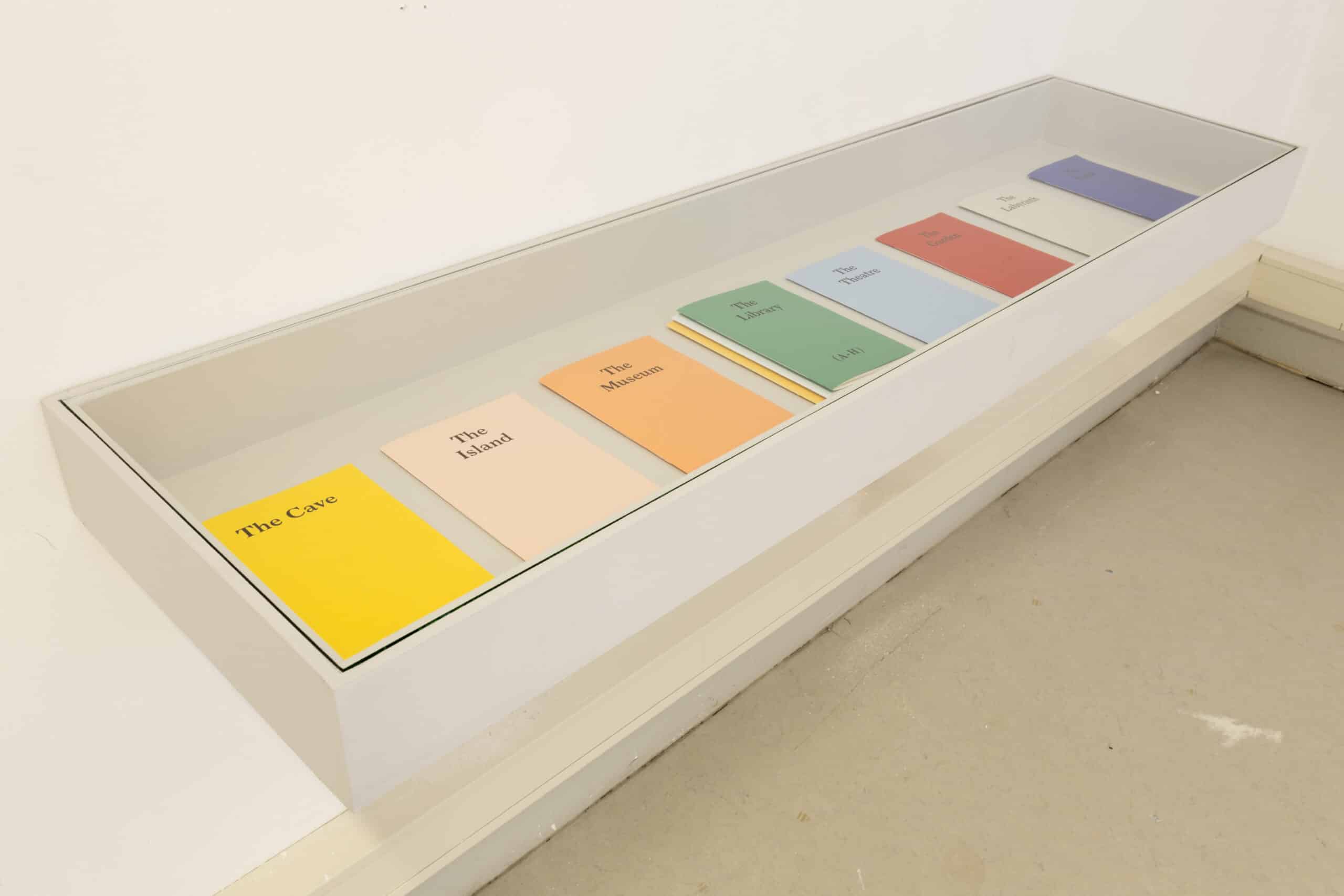

The chapter titles from Reads like a Book resurface in Binnerts’ recent project The Main Cast, which consists of booklets with a front cover in a plain colour – no cover image –, with words such as ‘The Library’ or ‘The Theatre’. They’re displayed in a glass cabinet, however, so that you can’t open them. You can only guess at what’s inside, but such words summon up clear associations for everyone, Binnerts notes; sometimes universal, sometimes personal (just like The Artist previously mentioned of course). Above all, they’re loaded words. An island as a setting can indicate emotional isolation on the part of the main character, for instance, or foreshadow their actually being cut off from the rest later.

Binnerts and I exchanged a number of these associations, although of course she knows what does and doesn’t appear in the books. It wouldn’t surprise me if they turned out to be empty, but that doesn’t make them any less exhilarating.

The Main Cast

The Main Cast