Anne Frank: The Vulnerability of a Universal Symbol

After the publication of her diary, Anne Frank became more than just a symbol of Jewish suffering during World War II; she transcended the 1940s to become a universal and timeless representation of innocence and victimhood. However, that second dimension is now under scrutiny.

A man barely survives his stay in Auschwitz but loses his wife and two daughters. He shares a similar fate with millions of other European Jews. What will make Otto Frank’s story unique, is that when he returns home, he finds the diary that his youngest daughter had written during the two years they spent in hiding. What’s more, in addition to the diary, he also finds a more literary reworking of the diary that she has made.

Otto Frank

Otto Frank© Jack de Nijs/Anefo

Otto Frank cherished the diary because it brought him into direct contact with his daughter’s inner voice, and indirect contact with the rest of his family, but at the same time, he experienced the intense need to share Anne’s story with the world. It allows him to let Anne and the rest of his family live on in one way or another, to ensure that people continue to know them and that they can continue to mean something to the world. He makes a new version in which he combines the original diary and its literary adaptation, and offers it to a publisher. For him, it’s a way to live on without his family.

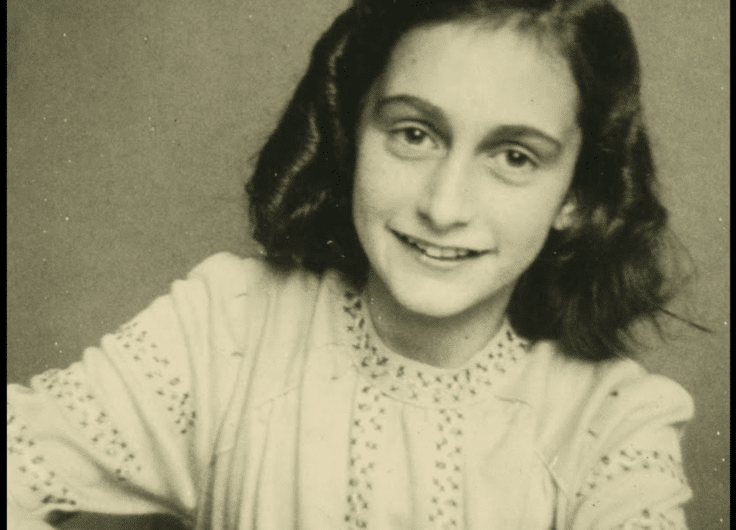

Especially after the successful American stage adaptation in 1955 and the film version in 1959, the book experienced immense success, and Anne Frank became the universal symbol par excellence of Jewish innocence and Jewish suffering. The diary has been translated into more than seventy languages, the stage adaptations are performed worldwide, and photographs with the smiling face of Anne Frank are instantly recognized.

Differences in emphasis

The universality of that process did not prevent the memory from being adapted to national or local needs. Although the overall story remained stable and universally recognizable, the accents in the way it was told sometimes differed greatly. These variations could relate to both the victim and the perpetrator. Was Anne Frank commemorated primarily as a child, as a girl, as a Jewish girl? Was she the victim of Nazi Germany or of any fascist or repressive regime, of Judeocide or of any genocide? Does Anne Frank offer a window on Dutch history, on the history of Judeocide during the Second World War, on the history of fascist violence or on the history of genocides over the centuries?

Anne Frank in 1942

Anne Frank in 1942© Anne Frank Foundation, Amsterdam/Public Domain

Some recent Dutch publications devote as much attention to these posthumous processes of signification as to the story of Anne Frank herself. This was done both in an academic volume and in a more popularising monograph by Ronald Leopold, director of the Anne Frank House. Both publications also reflect on the critical discussions about Anne Frank’s legacy. Broadly speaking, there are two. The first concerns the causes of Anne Frank’s success as a global symbol, and the second the effects. I use the term success here with some trepidation and in the full knowledge that it may come across as cynical in a text about a fifteen-year-old girl who was snatched from life in the most horrific way. It relates exclusively to the process of the imaging process, not to the life of Anne Frank herself.

The causes of success

The story of Anne Frank contains a large number of intrinsic ingredients that make its immense appeal understandable: the authenticity of the diary as a genre; the youthfulness and germinating literary talent of the author, who appears in almost all the photos with an irresistible smile; the combination of ordinariness and exceptionalism that emerges from the diary; the contrast between the hope of liberation and the mercilessness of the arrest; the sharp contrast between good and evil that runs like a thread throughout the story; the unsolved mystery of how the secret of the Secret Annex as a hiding place was discovered.

Many critics have remarked that the Americanization of the symbol of Anne Frank has led to a certain dumbing down

Yet it is also clear that these elements could only grow into a real hype because they were cast in a specific context by a specific group of people. Crucial in that regard were, of course, Otto Frank’s attempts referred to above to share his daughter’s legacy with the world. But he would have achieved that goal to a much lesser extent if a few American film and theatre makers had not appropriated the material. In the early Cold War context, the culture of the United States was more dominant than ever in Western Europe. Once it was incorporated into that culture, Anne Frank’s story was able to spread to large parts of the world.

In this respect, it differed from the stories that other Jewish girls or young women wrote down in their diaries during the occupation. Several of these diaries are dealt with in Frank van Vree and Martin van Gelderen’s A Jewish Child with Centuries Old Knowledge: Anne Frank as a Refugee, Writer and Icon, but none of them became as well-known as that of Anne Frank. None of these diaries were amplified in the same way by American purveyors of culture, although the diary of the Parisian student Hélène Berr certainly had the potential to do so. Many critics have remarked, and rightly so, that the Americanization of the symbol of Anne Frank has led to a certain dumbing down. But at the same time, this Americanization has helped millions of readers find their way to the original diary.

In attempts to understand the success of the icon Anne Frank, less attention has been paid to the fact that most of her life had taken place in the Netherlands. At the time that the Americanization and thus internationalization of her memory began, the war history of the Netherlands was still mainly bound to notions of heroism and victimhood. The fact that a significant percentage of the population and the government had collaborated received much less attention and a decolonial perspective on Indonesia’s war of independence was still extremely marginal.

The image of the innocent Anne Frank, who had been given shelter in the Netherlands from Germany and who had fallen victim to the National Socialist police services, fitted in well with that image of the innocent Netherlands. The two Dutch agents who had helped carry out the arrest came under scant scrutiny – and even less attention was paid to the broader system of administrative and police collaboration of which they were a part.

The image of the innocent Anne Frank fitted in well with that image of the innocent Netherlands

Even when in the 1960s and 1970s it became increasingly clear how large-scale the murder of the Jewish population in the Netherlands had been in comparison with other countries in Western Europe, the image of Anne Frank does not really seem to have shifted to examining the perpetration aspect. It even appears that the powerful symbol of innocence and victimhood that Anne Frank had since become had to some degree kept the Dutch perpetrators off the radar. In the Canon of the Netherlands, she is the window on the persecution of the Jews – and not the Dutch perpetrators or bystanders.

Thanks in part to Anne Frank, it seems, the powerful Dutch shared sense of national identity was virtually unaffected by sobering revelations in the 1960s and afterwards. Conversely, it is undoubtedly equally true that the icon Anne Frank was able to survive precisely because it had developed in a country whose sense of national identity was scarcely disputed.

What would have happened if the same diary had been written by a Jewish girl in Belgium? There is a good chance that the image of this diary would have shattered – just like it happened to the country’s entire memory of the Second World War. Not only would the language of the diary have determined the reach of its audience, but presumably a political battle would soon have arisen between heirs of the resistance and collaboration. References to the perpetrators and their supporters would have been used to discredit the political movement of which they had been a part. That movement – especially when it came to Flemish nationalism – would then have taken exhaustive measures to whitewash its collaboration with National Socialism.

Television series 'Children of the Holocaust'

Television series 'Children of the Holocaust'© VRT

In such a climate, there was little room to give the victims of the persecution of the Jews a face and a name. Only in recent years has this been happening, thanks in part to a television series such as Children of the Holocaust. But even today, Anne Frank’s name remains a more recognizable symbol in Belgium than that of the many victims or survivors of the Judeocide in their own country. This became apparent in 2017 when the municipal council of Lanaken in Limburg had to look for a new name for a street that was still named after the notorious collaborator Cyriel Verschaeve, and self-evidently came up with that of Anne Frank.

The effects of success

The effects of the successful portrayal of Anne Frank also raise the necessary critical reservations. Didn’t the depicted Anne Frank overshadow the memories of other victims of the Judeocide? Didn’t her story, which stopped before the deportation to Auschwitz, provide a too-sugar-coated picture of the reality of the murder of the Jews? Didn’t it contribute to an overly passive image of the Jewish population, and wouldn’t it have been better to focus attention on people who had actively resisted the German occupier?

Mother of Srebrenica in front of the Anne Frank House

Mother of Srebrenica in front of the Anne Frank House© Tarik Samarah, Memorial Center Srebrenica

An even more sensitive question is whether the successful memory of Anne Frank did not contribute to an overemphasis on the uniqueness of the Judeocide, and thereby kept other genocides out of the public eye. Has it – partly thanks to the Americanization of her surrender – taken up so much symbolic space that it has become virtually impossible to develop equally powerful icons around other genocides? Although thousands of innocent children also died during the genocides of the Herero in Namibia, the Armenians, the Tutsis in Rwanda, the Bosnians and many others, there is no symbol for those that are as recognizable worldwide as Anne Frank. But does this, too, contribute to the fact that these genocides remain underexposed? Or can the connection with Anne Frank help ensure that these tragedies continue to receive attention and are officially recognized as genocides?

In any case, the latter position is in line with the thesis defended by the American literary scholar Michael Rothberg in his writings on what he calls multidirectional memory. His starting point is that collective memory is not a zero-sum game, in which the memory of one suffering represses that of other traumas, but that they can mutually strengthen and enrich each other – at least if they continue to acknowledge each other’s individuality. This potential is fully recognised by the Anne Frank House itself, whose activities include collaborations with the War Childhood Museum in Sarajevo and organising travelling exhibitions in Rwanda.

Organisations that want to preserve the memory of other genocides often call on Anne Frank to give their message extra visibility. For example, in 2020, to mark the occasion of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the genocide in Srebrenica, the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience distributed a photo by Bosnian photographer Tarik Samarah showing a Mother of Srebrenica at the Anne Frank House looking at a photo of the Frank sisters at the beach.

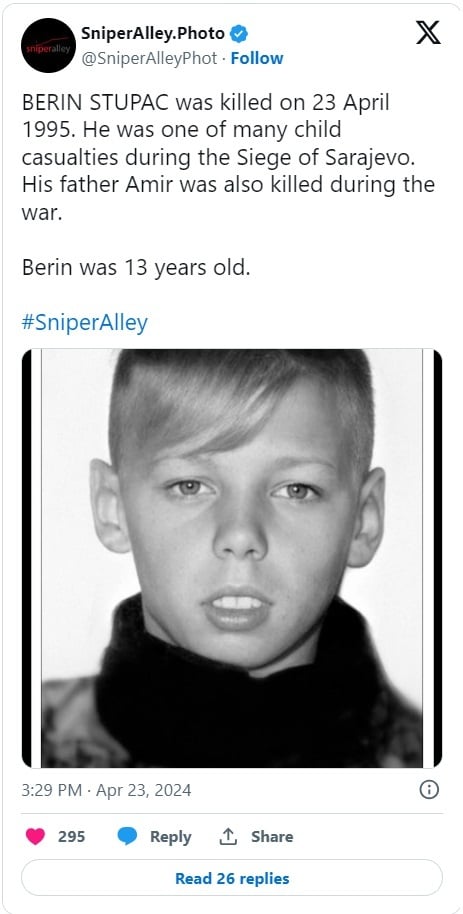

However, the question remains legitimate whether it would make sense for comparable symbols to develop around these other genocides that can step out of the shadow of Anne Frank. The previously mentioned War Childhood Museum dozens of heartbreaking testimonies and objects from victims of the Bosnian genocide of 1992-1995. Every day, The X account SniperAlley.photo tells the short story of all the children who died on that same date during the four-year siege of Sarajevo. If the story of one of those children were to be filmed by a top Hollywood director, the world might also become a little more sensitive to the precarious situation in which Bosnian Muslims still find themselves today.

Michael Rothberg illustrated the multidirectional effect of collective memory with that other iconic image of Jewish innocence during the Second World War: the boy who raises his hands after being arrested in the Warsaw ghetto. As early as 2011, Rothberg described how this image was also used in denunciations of Israeli policy in Gaza – not to equate the two, but to highlight the universality of children’s suffering in contexts of war and oppression.

An iconic image of Jewish innocence during the Second World War: the boy who raises his hands after being arrested in the Warsaw ghetto.

An iconic image of Jewish innocence during the Second World War: the boy who raises his hands after being arrested in the Warsaw ghetto.© Public domain

Anne Frank was also used in a similar way to express solidarity with the Palestinian people. As early as 2006, an image of her with a Palestinian scarf appeared in the streets of Amsterdam. Ronald Leopold included a photograph in his book Anne Frank: Life, Work and Meaning, matter-of-factly noting that the artist meant no offence, but in fact, wanted to contribute to reconciliation.

Between the space of time when Leopold wrote these words and when his book rolled off the presses (late October 2023), Hamas had carried out a horrific attack on Israeli settlements and the Netanyahu government had responded with ruthless retaliatory strikes in Gaza. On November 13, 2023, Turkish journalist Hilal Kaplan wrote in an op-ed for the English-language newspaper Daily Sabah how she heard “Echoes of Anne Frank in Gaza”: “Now as I am following many of what Gazans write here without knowing if they will survive the night and to know that this time the horror comes from those who capitalized on the misery of millions of people, akin to Anne’s ordeal, I am overwhelmed with a profound sense of nausea.” Two days later, on the Anne Frank House website, a shocked Leopold took a stand against the controversial slogan From the River to the Sea, which he heard chanted during pro-Palestinian parades, “because the slogan actually means a denial of the right of the State of Israel to exist.” It would be interesting to know whether, in this context, he would also have distanced himself from Anne Frank’s retrieval for the Palestinian cause.

Anne Frank with Palestinian scarf in Amsterdam

Anne Frank with Palestinian scarf in Amsterdam© Riekus Heller/Anne Frank Foundation, Amsterdam

Given current circumstances, the universality of Anne Frank as a symbol of innocence seems to be under more pressure than ever before. Shouldn’t she be stripped of much of her historical context for her to continue to fulfil that role? After all, in historical reality she was a Jewish girl whose family was looking for a safe existence and, in that context, also had close contact with Zionist circles. Can she be used as a symbol for a struggle in which a movement is taking the lead that openly denies the survival of Israel and is responsible for the deaths of more than a thousand innocent Jewish civilians? Or does the innocence that Anne Frank shares with the thousands of children in Gaza, who are defenceless at the mercy of a vengeful government in which genocidal voices predominate, take precedence?

The way out of this dilemma probably lies in the (renewed) reading of Anne Frank’s diaries themselves and of other texts left behind by defenceless victims of violence worldwide. They can show us the way to a shared humanity that is in danger of being lost in battlegrounds fuelled by symbols.

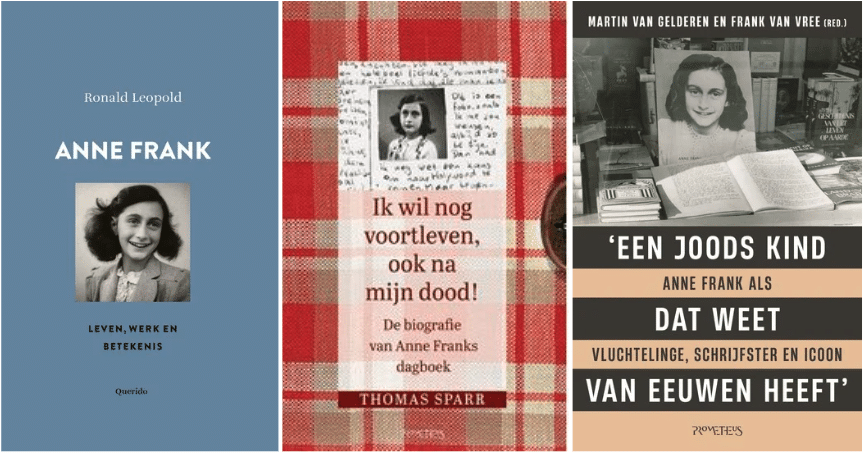

Martin van Gelderen & Frank van Vree (eds.), ‘Een joods kind dat weet van eeuwen heeft.’ Anne Frank als vluchtelinge, schrijfster en icoon (‘A Jewish Child With Centuries Old Knowledge: Anne Frank as a Refugee, Writer and Icon), Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2022, 400 p.

Ronald Leopold, Anne Frank. Leven, werk en betekenis (Anne Frank. Life, Work and Meaning), Querido, Amsterdam, 2023, 200 p.

Thomas Sparr, Ik wil nog voortleven, ook na mijn dood! De biografie van Anne Franks dagboek (I Want to Live On, Even After My death! The Biography of Anne Frank’s Diary), Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2024, 336 p.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.