Antwerp’s Expunged Protestant Past

Two Antwerp monks were burned at the stake five hundred years ago because of their Lutheran beliefs. They were the first martyrs of the Reformation. Their deaths remind us of a piece of the faded religious past of the Low Countries: Lutheranism and Calvinism first flourished in the South, with Antwerp as the focal point. That sixteenth-century reality was later expunged in the creation of an image, with the Catholic South versus the Protestant North.

On 30 September 2022, I led a group of Dutch mayors through sixteenth-century Protestant Antwerp. In the afternoon we were welcomed at the city hall by the Antwerp mayor. On that occasion, he regretted the Fall of Antwerp and the separation of the Netherlands and thanked the Dutch mayors present because in 1566 – the year of the Netherlandish Nobles Petition and the Iconoclasm – their predecessors had sent several Protestants to Antwerp.

Now Bart De Wever, himself trained as a historian, is usually very well informed about the past of his city, but at that time he too let himself be led by a misconception that is still widely held in Flanders: the image of the Protestant Netherlands and Catholic Belgium that would already find its roots in the religious developments of the sixteenth century.

However, the historical reality was completely different. Protestantism powerfully emerged first and most in the southern part of the Low Countries. So, before that, the movement was in reverse – from South to North. Antwerp did not need any help from Holland at all. That the Revolt against Spain would eventually rearrange the religious map of the Netherlands was originally impossible to predict.

Lutheran martyrs remembered

It is therefore a good thing that in Belgium one is occasionally reminded of that Protestant past. This happened, for example, in 2017, when five hundred years of the Reformation were commemorated and celebrated mainly in predominantly Protestant countries. On 31 October 2017 – five hundred years to the day after Martin Luther had posted his famous ninety-five theses in Wittenberg – the German ambassador to Belgium and the mayor of Antwerp inaugurated a Martin Lutherplein in the City on the Scheldt. It is no coincidence that the square in question was a stone’s throw from the Antwerp St. Andrew’s Church, the place where the Lutheran movement had a powerful start. After all, the St. Andrew’s Church, founded in 1529, dates back to the church of the Augustinian monastery in Antwerp. Monks of that monastery began to proclaim opinions from the pulpit that were in line with Martin Luther, their former order brother from Wittenberg.

Inauguration of Maarten Luther Square in Antwerp on 31 October 2017, including Mayor Bart De Wever (right)

Inauguration of Maarten Luther Square in Antwerp on 31 October 2017, including Mayor Bart De Wever (right)© International Lutheran Council

The repression of the “heretical” monastery led to another well-known event: on 1 July 1523, two Augustinian monks from the Antwerp monastery were burned at the stake on the Brussels Grand Place. They had refused to recant their Lutheran beliefs and the price they paid for their resolve was death. Hendrik Vos and Jan van den Esschen were the first martyrs of the Protestant Reformation in Europe.

Antwerp, centre of Lutheran ideas

The execution of the two monks reminds us how sixteenth-century Europe was torn apart by religious antagonisms. But there is more. It was no coincidence that the two monks came from Antwerp – at that time the expanding trading metropolis of the West par excellence. Martin Luther posted his ninety-five theses on 31 October 1517, in which he sharply criticized indulgence trading. As early as April 1518, writings by the Wittenberg church reformer were offered for sale in Antwerp and from 1520 Luther’s writings rolled off Antwerp printing presses. The fact that it all went so fast had to do with the cosmopolitan character of the City on the Scheldt. German merchants not only traded goods, but also brought with them new ideas and writings.

It was no coincidence that the two monks came from Antwerp

Perhaps even more important for the dissemination of Luther’s teachings was the presence of the Augustinian monastery founded in 1514, which belonged to the same branch as that of Martin Luther. Several monks of the Antwerp monastery had studied with Martin Luther in Wittenberg. Jacob Proost from Ypres, who as prior led the Antwerp Augustinian monastery from 1518 to 1521, was friends with the Wittenberg church reformer and openly proclaimed Lutheran views from the pulpit. His successor Hendrik van Zutphen, also an alumnus of the University of Wittenberg, did the same. Both priors were arrested at the instigation of the governor, Margaret of Austria, for their “heretical” activities, but managed to escape.

The events surrounding Hendrik van Zutphen show that the monks sympathetic to Martin Luther within the Antwerp city walls could count on a considerable amount of support and sympathy. At the end of September 1522, Van Zutphen was imprisoned in the nearby St. Michael’s Abbey while awaiting his transfer to Brussels. A chronicler noted that there was a great uproar in front of the gate of the abbey, “so that some came from the congregation, assisted by three hundred women, and they committed such violence in the room [where he was imprisoned] that they got him out.”

Hans Brosamer, Martin Luther preaching in a church, 1550

Hans Brosamer, Martin Luther preaching in a church, 1550© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The backlash: repression by the central government

For the governors, the liberation of Hendrik van Zutphen was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. In October 1522, the monks still present from the Antwerp Augustinian monastery were taken away and subjected to a religious examination. Most were willing to recant their errors, but three refused, including the aforementioned Hendrik Vos and Jan van Esschen. The third died in prison in Brussels in 1528. The Augustinian monastery complex was demolished. Only the church remained preserved and was transformed into a new parish church.

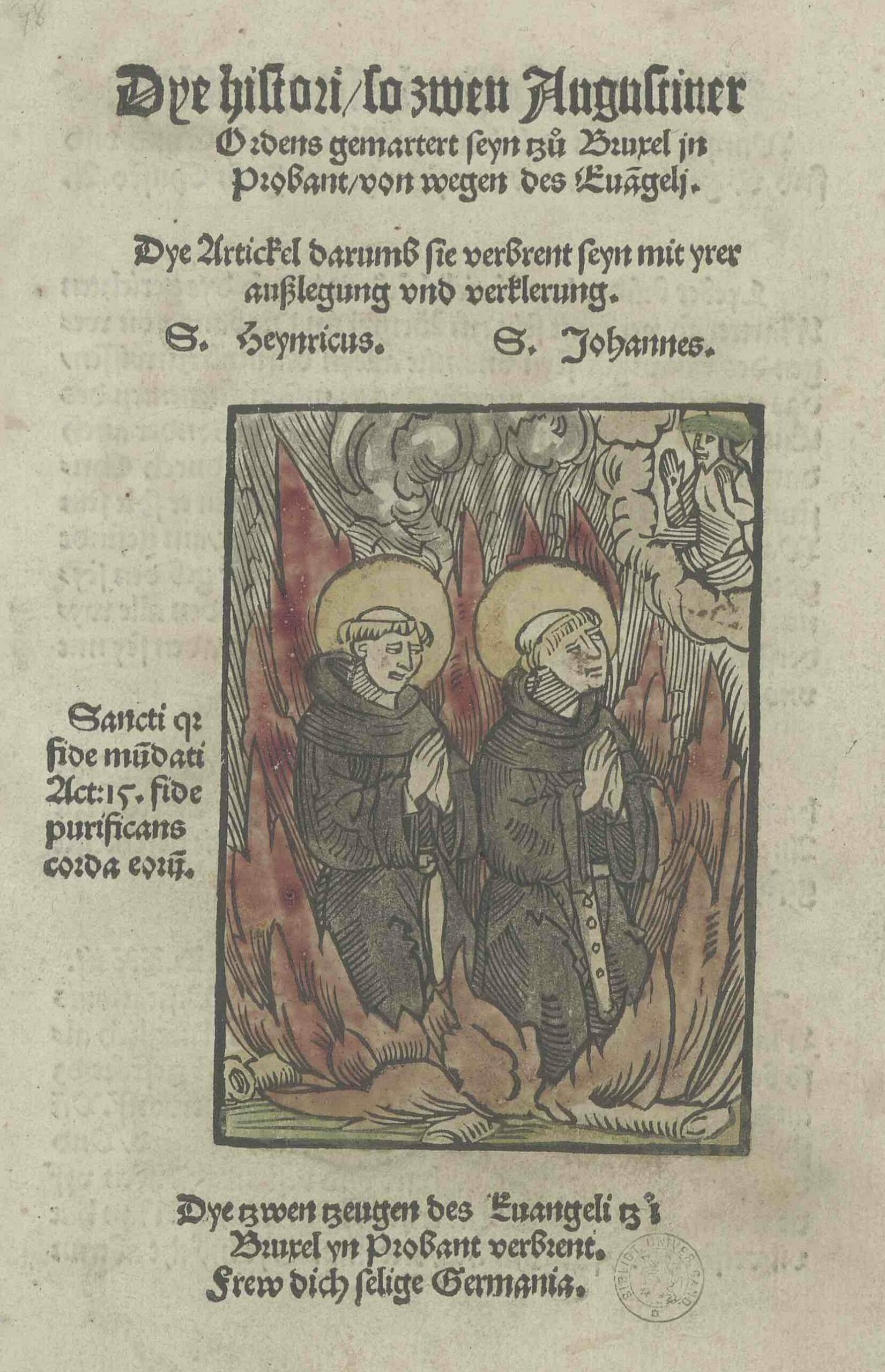

Hendrik Vos and Jan van Esschen, depicted as Protestant martyrs on the title page of 'Dye histori so zwen Augustiner Ordens gemartert seyn' from 1523

Hendrik Vos and Jan van Esschen, depicted as Protestant martyrs on the title page of 'Dye histori so zwen Augustiner Ordens gemartert seyn' from 1523© Ghent University Library

The driving force behind the persecution of the early Lutheran movement was not situated in Antwerp, but in the central government circles: it was Charles V, the governor and the imperial inquisitor Frans van der Hulst. The Antwerp city administrators kept a low profile earlier. A strict persecution policy could deter the foreign merchants desperately needed for the Antwerp economy, and that was the last thing they wanted to achieve.

Most Lutheran churches in the Northern Netherlands were founded after 1585 by expatriate Antwerp Lutherans

After the dismantling of the Augustinian monastery, Lutheranism in Antwerp lost its cornerstone. There were still Lutherans in Antwerp, but they worshipped their faith in silence. They proceeded to form an organized church only when it was made possible with the permission of the secular government. This happened during the Wonderyear (1566-1567) and in the period of the Calvinist Republic (1577-1585). In all those years, the Lutheran movement in the Low Countries remained an Antwerp affair to a large extent. Characteristic in this context is that most Lutheran churches in the Northern Netherlands were founded after 1585 by expatriate Antwerp Lutherans.

A new player: Calvinism

Around the middle of the sixteenth century, reformed Protestantism brought a new player to bolster the religious landscape in the Netherlands. This movement is also referred to as Calvinism, after its important architect John Calvin, although there were also other influences in the Low Countries. Calvinism developed rapidly, but here too the focus was initially entirely in the southern regions of the Netherlands. The first underground Calvinist churches were founded in Antwerp: a Walloon or French-speaking one in 1554 and a Dutch-speaking one in 1555. In Walloon cities such as Tournai, Lille, Valenciennes and Armentières, Calvinism developed especially strongly after the proclamation of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), which made it possible to cross the border with France practically unhindered. In the latter country, the French Huguenots already had a well-developed church organization. Contacts with fellow believers just across the border had a fertile influence. Another growth area was also located close to the border with France: the highly industrialized area of western Flanders with such places as Hondschoote and Nieuwkerke.

Antwerp's position as an international trading metropolis facilitated the Calvinist contacts and networks

Besides Tournai, it was mainly Antwerp that manifested itself as the leading centre of early Calvinism in the Low Countries. It was from the City on the Scheldt that the Reformed ideas were propagated to other places in Brabant, Flanders, Hainaut and Artois. Antwerp’s position as an international trading metropolis facilitated the contacts and networks that were set up. This also pre-eminently applied to contacts with the Reformed refugee churches in England and the German Reich. The connecting lines with centres such as London, Emden, Wesel and Frankfurt were largely based on Antwerp’s commercial channels. The intense interaction with the foreign refugee churches also makes clear how the early Calvinist movement was integrated into an international network.

That Antwerp was the great centre of Calvinism is also evident from the fact that all synodal meetings that were organized in the Netherlands before 1571, except for one, took place there. At these synods, representatives of the local churches – both French and Dutch – met to make joint agreements concerning doctrine and church organization. The synodal meetings initially remained a matter for the southern regions. Before 1566 there were Calvinist churches in Breda and in the Zeeland cities of Middelburg, Vlissingen and Veere, but not north of the major rivers. Breda belonged to the Duchy of Brabant and Zeeland in that period and was strongly connected with Flanders and Brabant both economically and culturally.

The Church of Ignatius in Antwerp, built in 1615-1621 by the Jesuits as an architectural statement of a triumphant Counter-Reformation.

The Church of Ignatius in Antwerp, built in 1615-1621 by the Jesuits as an architectural statement of a triumphant Counter-Reformation.© Wikimedia Commons

A militant Calvinism, linked to the Revolt

Calvinism was much better equipped to fight against a hostile government. Unlike Martin Luther, Calvinist church leaders had no problems establishing well-organized underground churches and forming networks that exceeded the local level. During the Wonderyear, the Calvinist church leaders fully engaged in the armed resistance against Spanish politics in the Netherlands. From now on, the course of military operations would largely determine the position of Protestantism in the various cities and regions.

Since the capture of Den Briel by the Beggars (1 April 1572), the Calvinist church in Holland and Zeeland had strong opportunities for development. In Flemish and Brabant cities Calvinism experienced a rapid expansion in the period of the so-called Calvinist republics (1577-1585). In 1577 it looked for a while that William of Orange would succeed in uniting most of the regions in the anti-Spanish resistance, but that soon turned out to be a vain hope. The Revolt increasingly took on the character of a civil war in which Catholics and Protestants confronted one other.

The Fall of Antwerp was also experienced by contemporaries as a turning point

When Alexander Farnese succeeded in conquering the rebellious cities in Flanders and Brabant one by one in the 1580s, a mass emigration began and the realm of the Protestants in the southern regions was finished. The Fall of Antwerp (17 August 1585) was also experienced by contemporaries as a turning point, although not necessarily as a definitive turning point. The military developments, which were partly determined by the international list of priorities of Philip II, would eventually lead to the formation of the Catholic Spanish-Habsburg Netherlands and the northern Republic of the United Provinces, where the Calvinist church was the only public, privileged church.

The Protestant past expunged

A process of religious-cultural reorientation was ushered in with the political and military consolidation. In those territories recaptured by the royal troops, that process proceeded in a counter-reformatory direction. Ecclesiastical and secular governments worked closely together to arrive at a confident and combative Roman Catholic faith. Through predications, catechism teachings and the printed word and image, the essential truths of faith were proclaimed and a stereotypical image of the enemy as the “religious other” was also created. The “Dutch” on the other side of the border were not only presented as pernicious heretics, but also as supporters of a reprehensible form of government.

Faith and propaganda led to a process of mental alienation within the scope of a single generation

At the same time, the public space in the cities underwent a profound change. New baroque churches were built, statues of Mary adorned facades of houses and in Antwerp even the façade of the town hall, the centre of political power par excellence. Processions passed through the streets with a fixed regularity. When in 1609 a truce was concluded between the warring parties and free travel in the Netherlands was again possible, many Protestants visited the cities they had fled from about twenty-five years earlier. To their surprise, they found that their hometown had changed profoundly, not just materially but also in the mindset of their inhabitants. All the efforts made through the proclamation of faith and propaganda had clearly done their job and led to a process of mental alienation within the scope of a single generation.

It is this same process of alienation that ultimately minimized or erased the memory of the Protestant past of Flemish and Brabant cities. Sixteenth-century Protestantism was reduced in those regions to a “foreign” import product while the native population would almost naturally be inclined to the Roman Catholic faith. That image would continue to haunt works of history and school textbooks of Catholic persuasion until the twentieth century. North of the major rivers, a picture of history emerged that went in the opposite direction. Historians of Protestant homes liked to emphasize that the Dutch were already inclined to Protestantism in the sixteenth century because of their “national character”.

We now know that this image did not correspond to sixteenth-century reality. The two Antwerp Augustinian monks who lost their lives on the Brussels Grand Place can remind us of this five hundred years on.