Playing with Stone: Architect Michel de Klerk Inspired the Amsterdam School

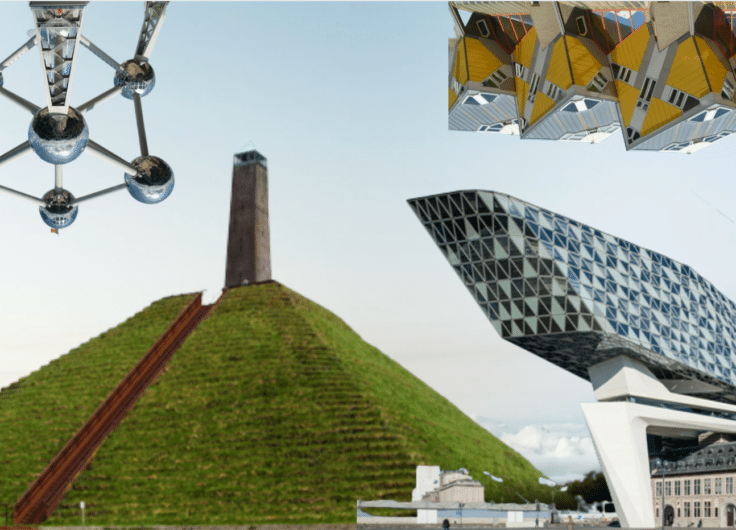

He realised unusual buildings, designed furniture, interiors and clocks, made countless drawings and produced graphic work. Yet architect Michel de Klerk still fell into oblivion. A beautiful exhibition at Museum Het Schip in Amsterdam rightly honours De Klerk as a central figure of the Amsterdam School, and places him among architectural innovators such as H.P. Berlage and Willem Marinus Dudok.

The reputation of an artist is a strange thing. Sometimes artists work in complete obscurity, but posthumously they may gain recognition and be remembered as one of the greats of their time. Now and then, however, the exact opposite happens. Regarded by contemporaries at home or abroad as one of the strongest forces of their generation, an artist’s name can disappear into the mists of time in the decades following their earthly presence. The architect and versatile designer Michel de Klerk (1884–1923) is such a person.

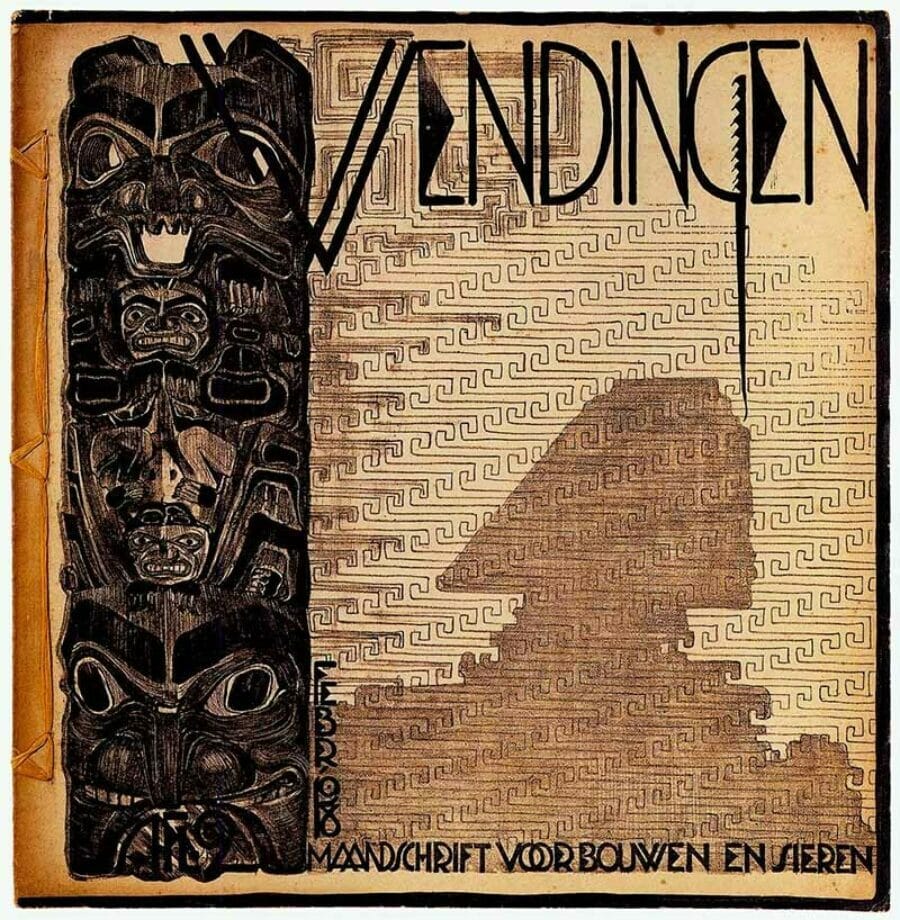

In Dutch architectural history of the early twentieth century, the names of Berlage, Dudok and Rietveld are the main ones to make an appearance. A beautiful exhibition at Museum Het Schip in Amsterdam shows that Michel de Klerk was one of the central figures in a movement that has become widely known: the Amsterdam School. After his early death on his thirty-ninth birthday (from pneumonia), no fewer than five issues on his work appeared in Wendingen, the magazine of the Architectura et Amicitia association, of which De Klerk was an active member. His buildings were also discussed in Flemish, French, British, Italian, Japanese and American magazines and books, usually in very favourable terms.

He did not receive much schooling, however. Born in Amsterdam in 1884, poverty prevailed in the Jewish quarter where he grew up, the son of a diamond-cutter. That neighbourhood provided fertile ground for the socialism that was then emerging. The ideals of that ideology returned in the “palaces for workers” De Klerk would later design, such as his De Dageraad and Spaarndammerplantsoen public housing estates.

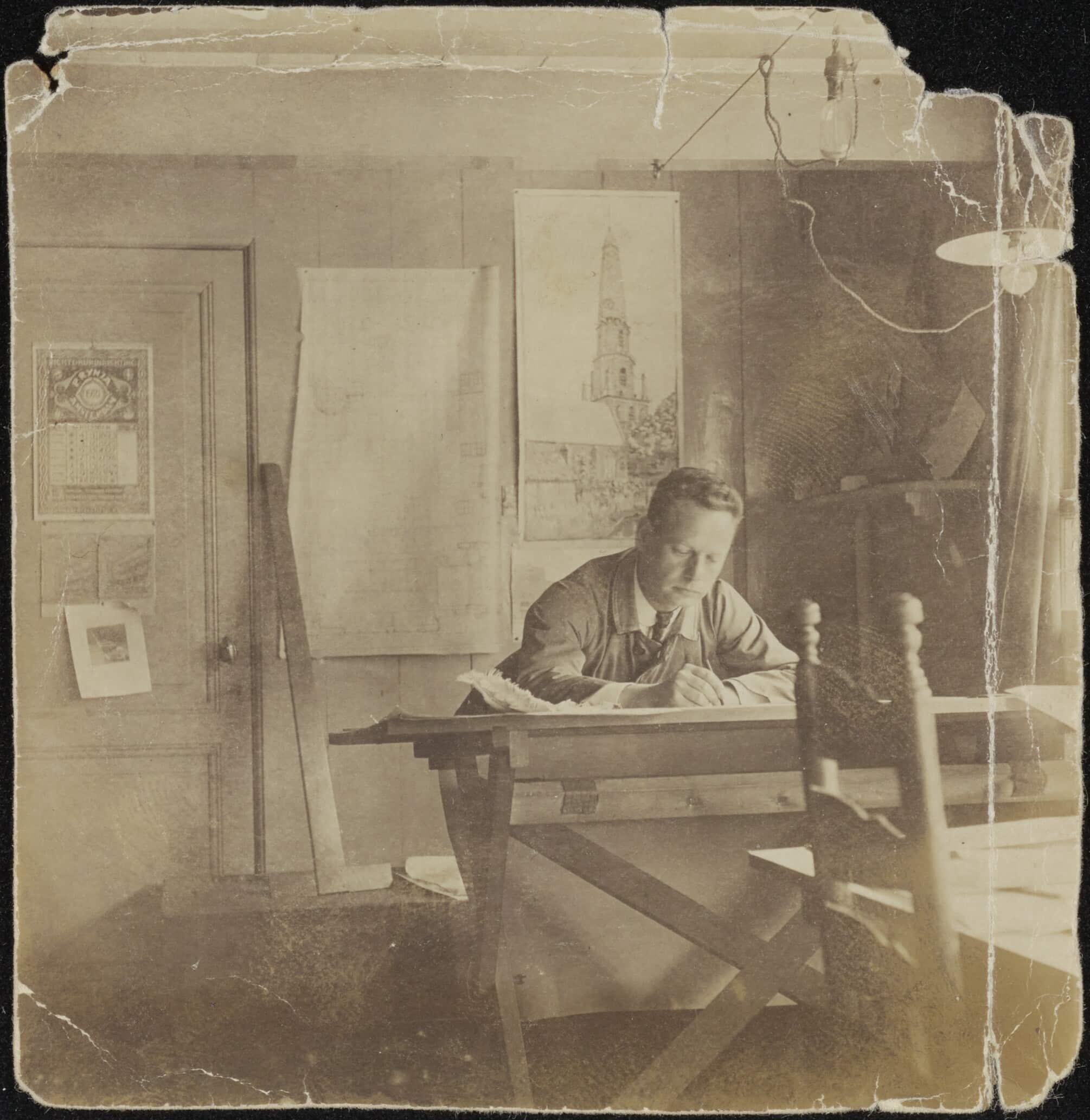

Michel de Klerk at his drawing table at the Baanders office on the Herengracht, 1922, unknown

Michel de Klerk at his drawing table at the Baanders office on the Herengracht, 1922, unknown© Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam

The young Michel, known as Sam, was good at drawing, and at some point, his talents drew the attention of the successful architect Eduard Cuypers, a nephew of the even more famous Pierre, architect of the Rijksmuseum and Amsterdam’s Central Station, among others. At fourteen, Michel went to work in Cuypers’ office, where the ideas of the English arts-and-crafts movement reigned supreme. Architects had to collaborate with craftworkers and also train in craft. De Klerk initially made drawings: sketches and portraits of people, but also designs of houses and residential areas, which he submitted to competitions in his own name.

Meanwhile, on trips and journeys to the UK, Germany and Belgium (in 1910 he visited the World Fair in Brussels), he gained inspiration for the company. Scandinavia, where he went on his honeymoon after marrying Lea Jessurun in 1910, impressed him the most. Anyone who sees the postcard De Klerk sent to a former colleague showing the tower of the Paladshotel in Copenhagen will recognise it as having inspired the later tower of Het Schip.

For the tower on the workers’ palace Het Schip (left), Michel de Klerk was inspired by the Paladshotel in Copenhagen (right)

For the tower on the workers’ palace Het Schip (left), Michel de Klerk was inspired by the Paladshotel in Copenhagen (right)© Marcel Westhoff / Museum het Schip

Because it sometimes made some money, De Klerk also drew to order: vignettes for companies, for example, what we would now call logos. He also took part in competitions to design posters, and received commissions via J.F. van Royen, an art-minded civil servant, for new coats of arms, letterboxes and stamps for the PTT (Postage, Telegraphy and Telephony Service).

De Klerk only really became an architect when he joined the Waanders brothers’ firm on a self-employed basis. His first built design was a residential house in Uithoorn: the brick façade, the relief with recesses and projections, the decorative details, the attention to fencing, window boxes, and gutters, all these characteristics would become even more prominent in his later oeuvre.

He had his breakthrough after that, with much larger buildings. The Hillehuis, a block of flats on Johannes Vermeerplein, was completed in 1912. Because the façade was conceived as one unit, numerous brick decorations broke through the austerity and De Klerk also designed the railings and door fittings, it is considered to be the beginning of the Amsterdam School.

De Klerk strove for a "Gesamtkunst" in which romanticism and fantasy prevailed

De Klerk was also involved in the design and construction of the most famous example of that movement. Joan van der Meij was the official architect of the Shipping House (Scheepvaarthuis) on Prins Hendrikkade, but in practice assistants Piet Kramer and Michel de Klerk did more than their share of the work. The budget was almost unlimited, which also showed in the luxurious interiors.

De Klerk was responsible for the boardroom of the Royal Packet Navigation Company, KPM (Koninklijke Pakketvaart-Maatschappij): he designed everything in that room himself, from the panelling to the wooden furniture, from the carpet to the ceiling lamp and the door with its bird-of-paradise decoration. It was the ultimate elaboration of the architecture De Klerk advocated, according to a rare text expressing his views. A Gesamtkunstwerk in which romanticism and fantasy prevailed, and which strove to ennoble “the art of industry and utility”.

Furniture designed by Michel de Klerk, 1916

Furniture designed by Michel de Klerk, 1916© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

He skillfully achieved such Gesamtkunstwerk in the three housing blocks on the Spaarndammerplantsoen that he designed subsequently. Flemish architect Huib Hoste, a pioneer of modernist architecture in Belgium, called the first building “one life of form and colour”. With its parabolic roof shapes, diverse use of materials, expressive brick construction and comical corner sculptures (a gnome with wooden clogs!), it showed something unprecedented, something entirely new. De Klerk definitively put himself on the map as the most important innovator of his time. The second housing block is based on the first, but with unusual masonry dressings (including herringbone and wave motifs), East Indies elements and the use of roof tiles as an illustrative element, it has its own character. Huib Hoste saw in this second block an extremely successful “relationship between buildings and open spaces”. He called it an “example of one of the ways in which the modern square can be solved” and wanted “all of building Amsterdam to go and see it”. What Hoste thought of the third housing block on this park is not known.

The second of three housing blocks by Michel de Klerk for the Spaarndammerplantsoen in Amsterdam, circa 1920

The second of three housing blocks by Michel de Klerk for the Spaarndammerplantsoen in Amsterdam, circa 1920© Bernard Eilers / Museum het Schip

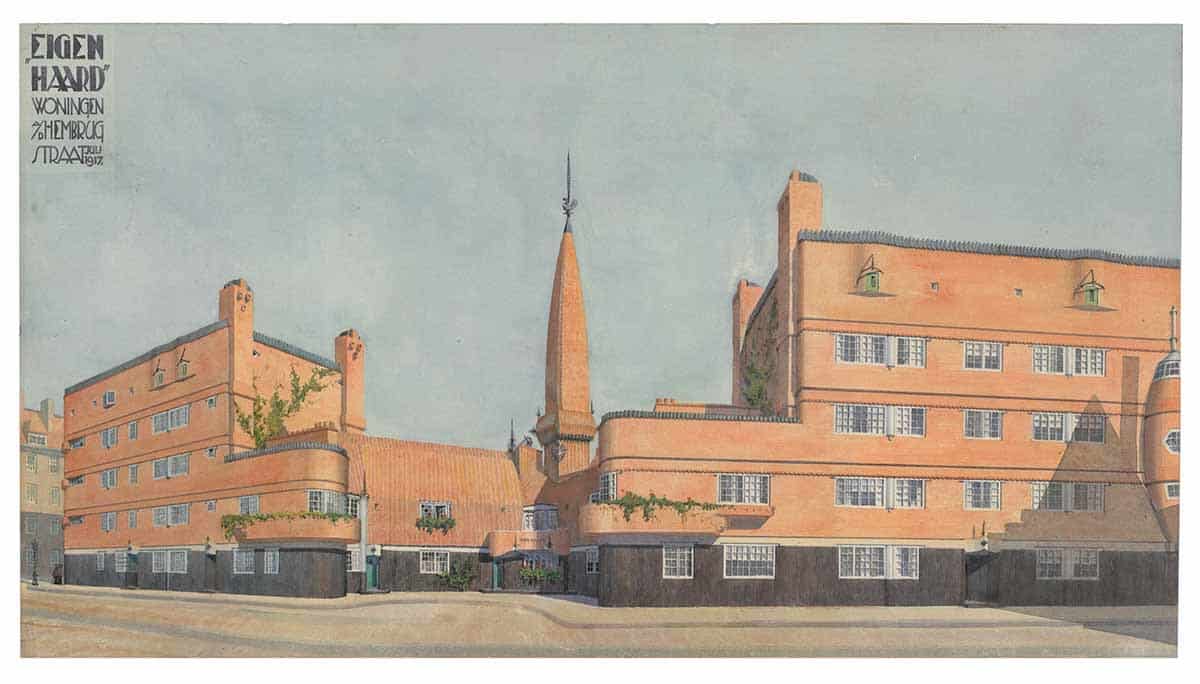

Commissioned by the housing association Eigen Haard, for which he also designed the logo, De Klerk drew the most memorable of all his designs: Het Schip (now home to the museum of the same name, which features the exhibition on De Klerk). On an awkward triangular plot, the building stands out for its bright orange-red Groningen brick, the combination of horizontality with verticality and its almost misshapen bay window protrusions (“cigars”). As in the second block on the Spaarndammerplantsoen, the alternation between open and closed spaces is surprising and well thought-out, and even more than there, East Indies motifs are integrated into the design – that De Klerk had a Chinese-Indonesian collaborator in Liem Bwam Tjie may explain this emphasis. But the real eye-catching details of the building are its little postroom, a brilliant example of Amsterdam School interior design, and slender, useless, but highly aesthetic turret: a “pure emotional motif” according to some, “virginally fragile” according to others.

Illustration of housing Spaarndammerplantsoen aka Het Schip, 1927

Illustration of housing Spaarndammerplantsoen aka Het Schip, 1927© Nieuwe Instituut

Het Schip impressed far beyond the country’s borders. “In a few years, any stranger who looks it up in Baedeker [a travel guidebook] will be able to ask you about it,” judged one reviewer. The architectural weekly Bouwkundig Weekblad reported that elite circles “in London, Berlin and Vienna” were marvelling at the building. Recognising German influence, the reviewer in the Francophone Belgian newspaper Le Soir found the district “monstrous”, but also cited Maurice Maeterlinck’s tragedies and the work of Henry Van de Velde as references. That De Klerk had created a new landmark with Het Schip and its turret is perhaps best demonstrated by a design by the very young Renaat Braem. As an eighteen-year-old student at the Antwerp Academy, the later modernist and rationalist drew the poster that would announce a school excursion to Amsterdam. The central image is not the Rijksmuseum or Central Station, nor the Beurs van Berlage, but the slender tower of Het Schip.

The emblem of housing association Eigen Haard, designed by Michel de Klerk, 1920

The emblem of housing association Eigen Haard, designed by Michel de Klerk, 1920© Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam

When De Klerk died in November 1923, he had fortunately just managed to witness the completion of the first homes in his latest housing complex: De Dageraad, the fruit of a collaboration with his friend Piet Kramer and part of Berlage’s Plan Zuid urban development. What catches the eye is the monumental, undulating corner construction that gives the building a very different cachet than one was used to seeing in housing estates. The reactions were unanimous: “What rich imagination and what command of form!”, wrote one architecture critic. Bouwkundig Weekblad discerned a certain enigma in De Klerk’s architecture, which confused the viewer: “Is it Baroque, is it Expressionism, is it a piece of bravado, is it a confession, is it daredevilry, or is it proof of mastery?” Then again, the magazine was enthused by the way the squares had been tackled: it showed “the mood one finds in Bruges, in its beguinage”.

Het Schip by Michel de Klerk impressed far beyond the country’s borders

Due to his early death, the number of completed buildings by De Klerk has remained limited. But his oeuvre is much larger, as the five themed issues of the magazine Wendingen after his death showed. Where the first was dedicated to his completed buildings, subsequent issues focused on his drawn portraits, his travel sketches, the furniture he designed (some of which was exhibited at the famous 1925 Art Deco Expo in Paris) and, finally, the un-realised architectural designs. And there could have been more issues – for example on his ex libris, cover designs (for Wendingen, but also for books) and other graphic work.

The exhibition in Het Schip duly attends to the afterlife of De Klerk and his designs. Shortly after his death, romantic architecture fell out of favour. Functionality, rationality and clear lines stepped into its place, an architectural style that aimed for transparency, clarity and repeatability. The designs of the Amsterdam School had become something to oppose; the name Michel de Klerk disappeared from the minds of architecture enthusiasts relatively quickly.

Cover of 'Wendingen', the magazine of the society Architectura et Amicitia, designed by Michel de Klerk

Cover of 'Wendingen', the magazine of the society Architectura et Amicitia, designed by Michel de Klerk© Museum het Schip, Amsterdam

It was not until the 1960s, through publications in the UK, Germany and the US, that his name occasionally resurfaced. The first monograph on De Klerk, written by Suzanne S. Frank, was published in the US in 1970. In the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, interest in the Amsterdam School grew little by little, also in the Netherlands – although it was not until the mid-1990s that a number of De Klerk’s designs were classified as national monuments. The first monographic exhibition on his work came in 1997, at the NAi in Rotterdam, today’s Nieuwe Instituut, where, among other things, De Klerk’s archive is held and can be consulted for research.

Twenty-seven years later, a hundred years after his death, the mostly introductory exhibition at Het Schip makes it clear that, alongside Berlage and Dudok, we might remember De Klerk’s name as a great innovator of Dutch architecture. He was no theorist – he hardly formulated any explicit positions or design principles and you will not find them in the exhibition. But his unusual and extravagant buildings, furniture, clocks, drawings and other designs speak for themselves. To quote Wendingen editor-in-chief Hendrik Wijdeveld: Michel de Klerk was “the most childlike and powerful” of architects, he “played with his forms in the unfettered realm of his fantasies”.

K.P.C. de Bazel, a contemporary of that playful architect of the majestic palace on Vijzelstraat that now houses the Amsterdam City Archives, called De Klerk “one of the few with the gift of animating stone and bringing it to life”. Unfortunately for him, De Bazel died while on his way to the funeral of his gifted colleague. On the train from Bussum to Amsterdam, he suffered a heart attack.

Michel de Klerk. Inspirer of the Amsterdam School can be visited until 1 September 2024 at Museum Het Schip in Amsterdam, www.hetschip.nl

The catalogue Architect and Artist Michel de Klerk. Inspirer of the Amsterdam School, by Ton Heijdra & Alice Roegholt is also available in English.