Lernu Esperanton: Why Writers Embrace Artificial Languages

When no well-known language can adequately express what you want to convey, what do you do? For a few bold writers in the Low Countries, the answer was clear: they chose a new language, such as Esperanto, Ido, or Volapük. Marc van Oostendorp, an Esperanto enthusiast himself, rediscovers three writers who found their unique voice in an artificial language.

Writing is making choices, and the first choice of every multilingual writer is: which language to write in? Do you choose the language or dialect of your daily life, and perhaps that of your characters? Or do you go for a more widely spoken language to reach a broader audience?

Portrait of Lejzer Zamenhof (1859-1917), Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist and creator of Esperanto, painted by Felix Moscheles

Portrait of Lejzer Zamenhof (1859-1917), Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist and creator of Esperanto, painted by Felix Moscheles © Wikimedia Commons

Both options are valid, yet writers sometimes choose a language that is not their native tongue, not spoken by the people around them, and rarely spoken elsewhere, with no native speakers. A language that, unlike Dutch, Chinese, or Arabic, didn’t naturally develop over time, but was crafted deliberately, such as Esperanto, introduced in 1887 by Polish-Jewish ophthalmologist Lejzer Zamenhof for international communication, or Dothraki, created in the 21st century by American David Peterson for the TV series Game of Thrones. They are languages that have no native speakers, nation, or historical heritage. Why would anyone ever want to write stories or poems in such a language?

Some writers are driven by idealism, aiming to expand the language’s global reach through their literature. Other authors believe this language offers greater potential to express themselves. The language’s artificiality gives them greater freedom to find their own distinct voice.

Occasionally, writers with similar views emerge in the Low Countries. For obvious reasons, they didn’t find a large audience, but that doesn’t seem to bother them. Three of them are worth remembering: Andreas Juste, Hendrik Jan Bulthuis, and Bertus Smit.

Artificial languages

Juste, Bulthuis, and Smit belong to an idealistic lineage: they used languages designed to serve as global languages. This idea gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Technological advancements such as rail networks and telegraphy had simplified international communication, yet language barriers remained an obstacle. It was a time with great faith in human progress: if existing languages were too complex with their irregularities, and if established global languages such as French or German were too politically charged, couldn’t people simply create a new language that was simpler and more neutral?

The idea that artificial languages could serve as global languages gained popularity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries

The most well-known example is Lejzer Zamenhof’s Esperanto, which remains the most widely used, with an estimated hundreds of thousands of speakers worldwide – but there are certainly hundreds of other languages like this, including Mondial, Interlingua, and Latino sine flexione.

Over time, languages have been created for various purposes. In recent decades, languages have often been created for fictional worlds in fantasy movies and Netflix series such as Game of Thrones, Dune, and House of the Vampires. An earlier example is J.R.R. Tolkien, who created Elvish languages for The Lord of the Rings. Although fans have learned these languages; they haven’t inspired the same level of literary enthusiasm as idealistic languages from around a hundred years ago.

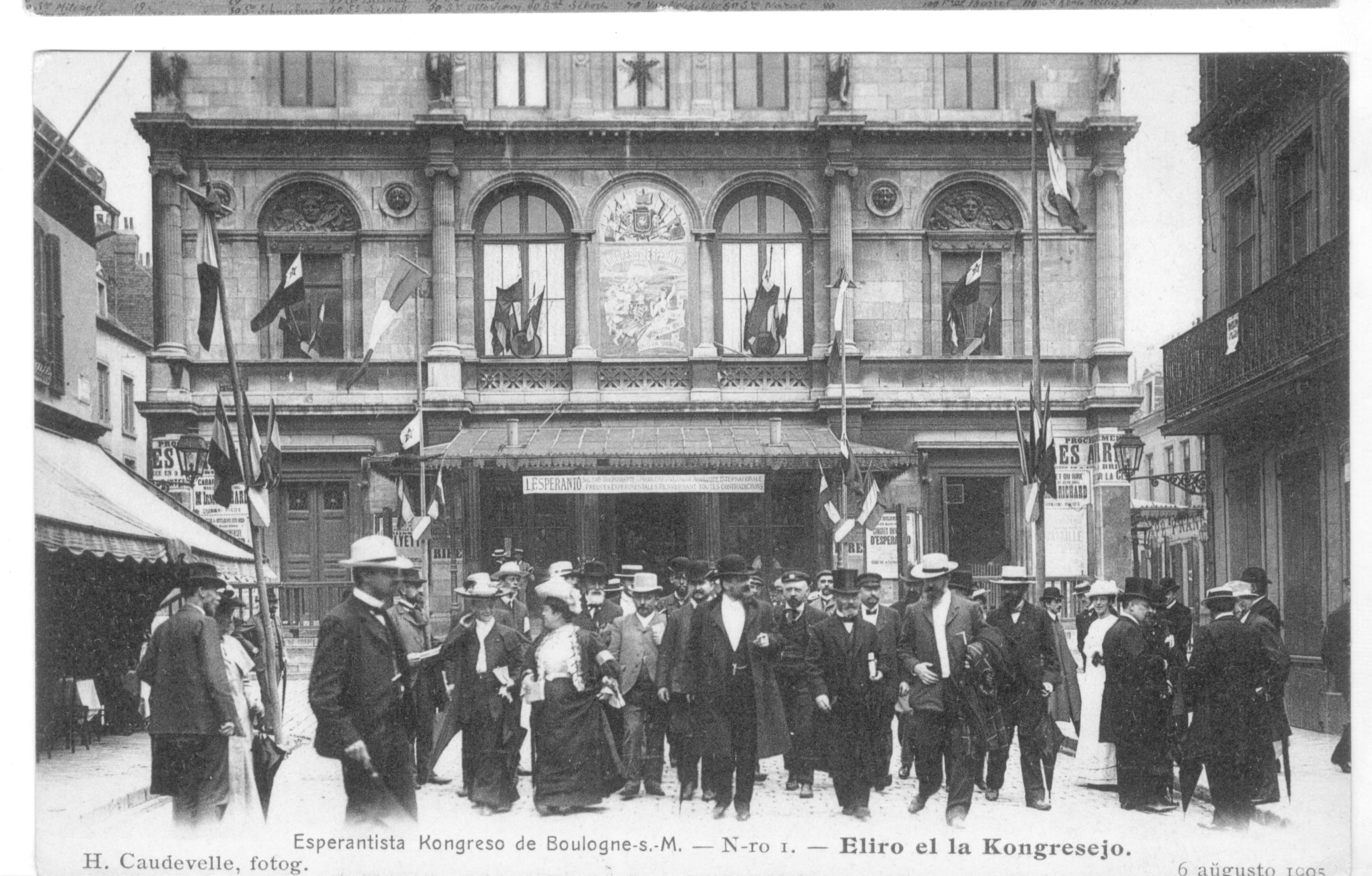

The first Esperanto World Congress took place in 1905 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France

The first Esperanto World Congress took place in 1905 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, France© Wikimedia Commons

An isolated lawyer

The most talented poet of artificial languages in the Low Countries was Andreas Juste (1918-1998), a lawyer from Charleroi. After World War II, he discovered Ido, an “improved Esperanto” that emerged at the start of the 20th century. At the time, a group of French intellectuals believed that grammatical issues with the original Esperanto had limited its broader acceptance. To address these problems, they replaced the Greek word kaj for and, used the Latin ed, removed unusual characters such as ĉ and ĝ, and so on. The outcome was a language identifiable as an Esperanto dialect (for example, ido translates to descendant in both languages).

Andreas Juste wrote his entire oeuvre in Ido, an improved form of Esperanto

Andreas Juste wrote his entire oeuvre in Ido, an improved form of Esperanto© Wikipedia

Following a heated rivalry between Idists and Esperantists, the Idist movement had largely dissipated by the end of the war. That was until Juste discovered that the language aligned perfectly with his thoughts and emotions.

Over the roughly fifty years between his discovery and his death, Juste created an impressive oeuvre in Ido: plays, essays, translations, stories, and numerous poems. He partially self-published his work, while the other part never left his study. When clearing out his room after his passing, his children discovered approximately two hundred works that they couldn’t read. Today, the archives reside in the National Museum of Austria, home to the world’s largest collection on artificial languages.

Here is an example of a poem by Juste, written in Japanese style:

De la palaco

Nur un kolono restas

En sola staco;

Ed ibe sur la kresto

Cikoniala nesto

(From the palace, only one solitary column remains; With on its capital, a stork’s nest)

It’s a moving image in five lines, which can also be seen as a metaphor for Ido poetry: on the lonely remains of great ideals, the poet builds a nest. This interpretation is supported by the recurring image in Juste’s work of a poet, who sings in total isolation in an envisioned universal language. He used his work to keep the language he cared for alive.

A civil servant among the Balkan poets

That sense of isolation was far less evident for the Dutch novelist Hendrik Jan Bulthuis, though he belonged to a different generation. He lived from 1865 to 1945, during a time when there was great enthusiasm in society for the idea that the problems of international communication could be solved by a language that was easy to learn and, just for that reason, more democratic than the difficult national languages.

In his youth, Bulthuis’ heart had originally beat for another artificial language, Volapük. This language was briefly popular in Europe before Esperanto, but the movement fell apart due to internal disputes by the end of the nineteenth century. One point of conflict was who had the authority over Volapük – the original creator, the German priest Johann Schleyer, or the language community as a whole. (There is still a Wikipedia in Volapük, but to my knowledge, there are no longer any people seriously advocating for this language as a universal language.) Bulthuis joined many other Volapük supporters in switching to Esperanto, which had the benefit that its creator did not claim copyright.

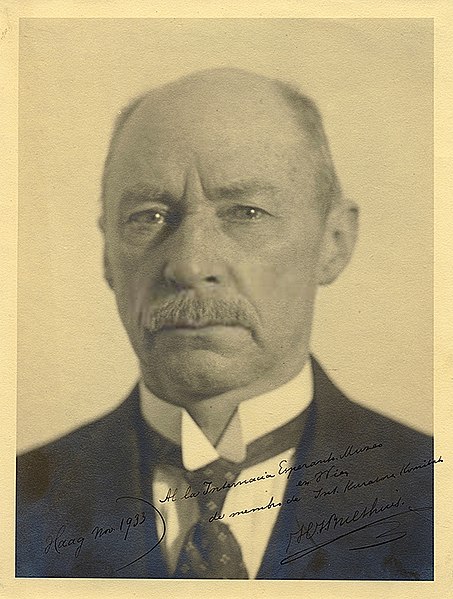

Dutch novelist Hendrik Jan Bulthuis translated a few literary classics into Esperanto.

Dutch novelist Hendrik Jan Bulthuis translated a few literary classics into Esperanto.© Wikipedia

Bulthuis had worked his way up from farmer’s son to tax official in the Hague in just a few years, but since he discovered Esperanto in 1901, he dedicated nearly every free moment to the language. He translated quite a few works, including nineteenth-century classics like Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë, Kejser og Galilæer (Emperor and Galilean) by Henrik Ibsen, De kleine Johannes (The Small Johannes) by Frederik van Eeden, and De leeuw van Vlaanderen (The Lion of Flanders) by Hendrik Conscience. He also wrote three lengthy novels and a novella. Meanwhile, he lived as frugally as possible, so that he could retire early in 1924 at the age of fifty-nine and fully dedicate himself to writing in Esperanto.

One of his three novels is named La vila mano (The Hairy Hand) and is often regarded as his best. A significant part of it is a regional novel set in the Groningen of Bulthuis’ youth, with an element of fantasy: the hairy hand in the title is a disembodied hand of an orangutan that disrupts the lives of the villagers. The book was later translated and adapted by Hendrik Jan’s son Rico Bulthuis, and was published in 1977 under the title De tavernee van Piet Rabbel (The Tavern of Piet Rabbel). Here are the first sentences of the original and the adaptation for comparison:

Peĉjo Klakilo (en realo lia nomo estis Peter Blunt) kviete sidis sur la kanapo kaj deklamis la supre cititan kanton, akompanante ĝin per laǔtaj klakadoj de siaj manoj, brue kunfrapante ilin ĉe ĉiu akcentigata silabo, kiun li plilaǔtigis.

Pieter Blunt, who was known in the village as Piet Rabbel, sat on a leather couch in the large tavern room of his establishment ‘The Green Horse’, softly reciting the old rhyme ‘Pierlala lay in the coffin’ that he had learned from his mother. He clapped his hands to the beat of the rhyme with delight, as he was always in a great mood when he recited in this way.

Hendrik Jan’s son Rico Bulthuis (1911-2009) later became a writer himself, but he wrote in Dutch. In his memoir De dagen na donderdag (The Days after Thursday), he described how, for the perfectly respectable civil servant family in the Hague, “evenings at their home were characterized by garlic-smelling Esperanto poets from the Balkans talking about the golden future that was to come when the brilliantly constructed global auxiliary language was introduced in all schools!”

Hendrik Jan Bulthuis also became the patriarch of a still-prominent artistic Dutch family. Rico was the father of the well-known actress Sacha Bulthuis (1948-2009), who, in turn, is the mother of the well-known actors Aus (jr.) and Pauline Greidanus.

Poster promoting Esperanto

Poster promoting Esperanto © International Institute of Social History

A fascist Esperantist

A much less prominent place in society was held by the Amsterdam-born Bertus (or Alberto) Smit (1897-1994), the artificial language poet who lived the most turbulent life of his time. He was likely conceived by a German cardinal from an aristocratic family and a Dutch nurse. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, he entered the bizarre world of Dutch fascism – although he was the kind of fascist who rejected mainstream National Socialism from the very beginning.

At the end of the war, he was placed in a German concentration camp because he had severely criticized Hitler in the brochure Führer, de doden klagen u aan (Führer, the Dead Are Accusing You). After the war, he became involved in an organization that promoted Dutch-American relations, and later participated in the squatter protests against the construction of a metro line around the Nieuwmarkt in Amsterdam.

A poetry collection in Esperanto by Bertus Smit

A poetry collection in Esperanto by Bertus Smit© Wikipedia

Meanwhile, he constantly changed professions. In his booklet Een man van vele namen (A Man of Many Names, 2017), biographer Willem Huberts details: “tailor, shoe salesman, store clerk, propagandist, poet, political activist, historian, sales representative, translator, illustrator, and journalist.” He adds: “The list is still not complete.”

Yet, in addition to all this, Smit wrote poetry in Esperanto, usually with a slightly sentimental tone. It’s a strange combination, fascist and Esperantist, particularly because Esperanto was invented by a Polish Jew to bring people closer together. I see little fascism in Smit’s poetry. Here is the beginning of a poem from his collection Roseroj (Dewdrops) from 1930:

Al pola amikineto

En profunda la interno

De grand-urba lu-kazerno,

Meze de la urba zum’

Malproksime de la lum’,

Inter tute kalvaj muroj –

Grize flavaj kaj malpuraj,

Loĝas mia etulin’,–

Ĉarma, bela junfraǔlin’.

(To a Polish girlfriend: In the depths of an urban rental building, surrounded by the city buzz, far from the light, between completely bare, gray-yellow, and dirty walls, lives my little one, – a charming, beautiful young woman.)

The life of Alberto Smit is, much like that of Juste and Bulthuis, perhaps more interesting in hindsight than his actual work. All three devoted many hours of their lives and their best efforts to a language, mostly without anyone around them knowing. For Juste, it was mainly about the idea that this particular language could express exactly what he wanted to say; for Bulthuis, it was the desire to help build a future global language through his work; and for Smit, it was part of a restlessness that would take him in many directions later in life.

Their efforts have produced bookshelves filled with works that only a handful of people can understand. Some writers choose their language not to reach those around them or to aim for a bestseller, but because they write for future generations – who they hope will be able to read their language – or simply because they fall so deeply in love with a language that they don’t care who can read their work.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.