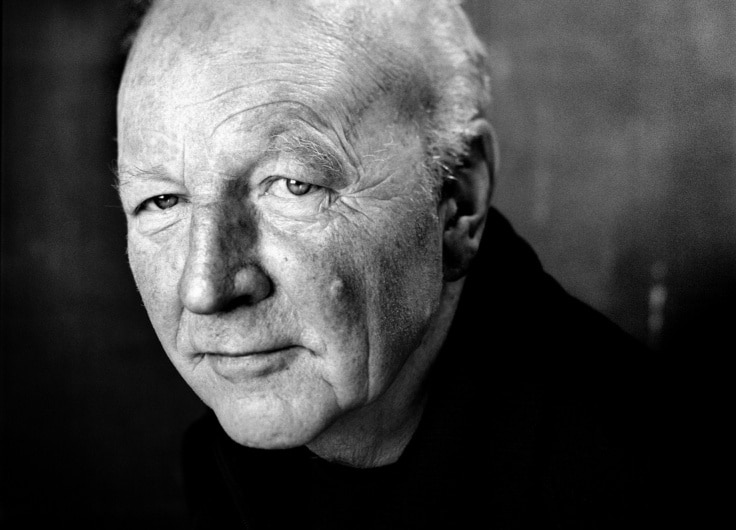

Aster Berkhof (1920-2020): The Man of 101 Books and Too Little Recognition

Writer Aster Berkhof died on 29 September 2020. He turned 100 years old. In Flemish libraries, for many years, his novels would be some of the most frequently checked out items. However, in the official annals of literature, a mere two lines are dedicated to the author. The popular novelist was never awarded many important literary prizes. Still, he deserves a lot more recognition, as next to books we would consider ‘light reading’, he also wrote several ‘serious’ novels, which aptly capture societal developments in Flanders in the aftermath of World War II.

‘I love Earth, yet live at odds with the world,’ Berkhof writes about himself in De zomer en ik (The Summer and I), a collection of autobiographical notes published in 1982. He continues to present himself as having great expectations for nature, as a sun-worshipper (he never writes in summer, that is when he wants to live), longing for the outdoors and manual labour, with a penchant for simple yet tasty food (and also: ‘I think making love is a pleasurable pastime’). You cannot disconnect him from this vitality; he will propagate it for eternity.

Around 1980, however, that same vitality is forced to give way in part to a growing resentment against all that is wrong with the world. Because of what people want to do to one another. Because of how people choose to be. That resentment first – and most strongly – surfaces in Berkhof’s trilogy comprising Toen wij allen samen waren (When We Were All Together, 1979), Mijn huis in de verte (My House in the Distance, 1980) and Leven in de zon (Living in the Sun, 1981), a charge against opportunistic conservatism, political trickery, corruption and manipulation. He confronts those with the notion of freedom and authentic self-determination.

Special powers

Traces of Berkhof’s ideas can already be found in his earlier work, in accordance with the spirit of the sixties. In Dagboek van een missionaris (Diary of a Missionary, 1962), missionary Paul Winters tries not to be thrown of balance during India’s and Pakistan’s growing independence, which saw mass migrations and bloody conflict at its tail end. He starts to doubt the one soul-saving message he is supposed to spread. He ends his diary by putting out a call for Christians and Hindus to collectively move towards the future. Hindus and Christians on equal terms?

Around 1980, Berkhof's vitality is forced to give way to a growing resentment against all that is wrong with the world

In Het einde van alles (The End of Everything, 1965), set in impoverished Calabria, chaplain Renato takes the fate to heart of the poor souls up in the mountains, who were left to their own devices by the governments, and were in danger of falling into the hands of the communist rebels. But Renato is also faced with superstition, in the shape of a tiny silver cross that belongs to him and which his Christian disciples attribute with special powers. This is not the faith he preaches.

As he is confronted with the terrible fanaticism of all the warring parties in the Spanish Civil War, Father Luis Herrera’s calling in De woedende Christus (The Furious Christ, 1965) is replaced by doubt, and he starts to see more advantages in practising solidarity than in preaching the gospel.

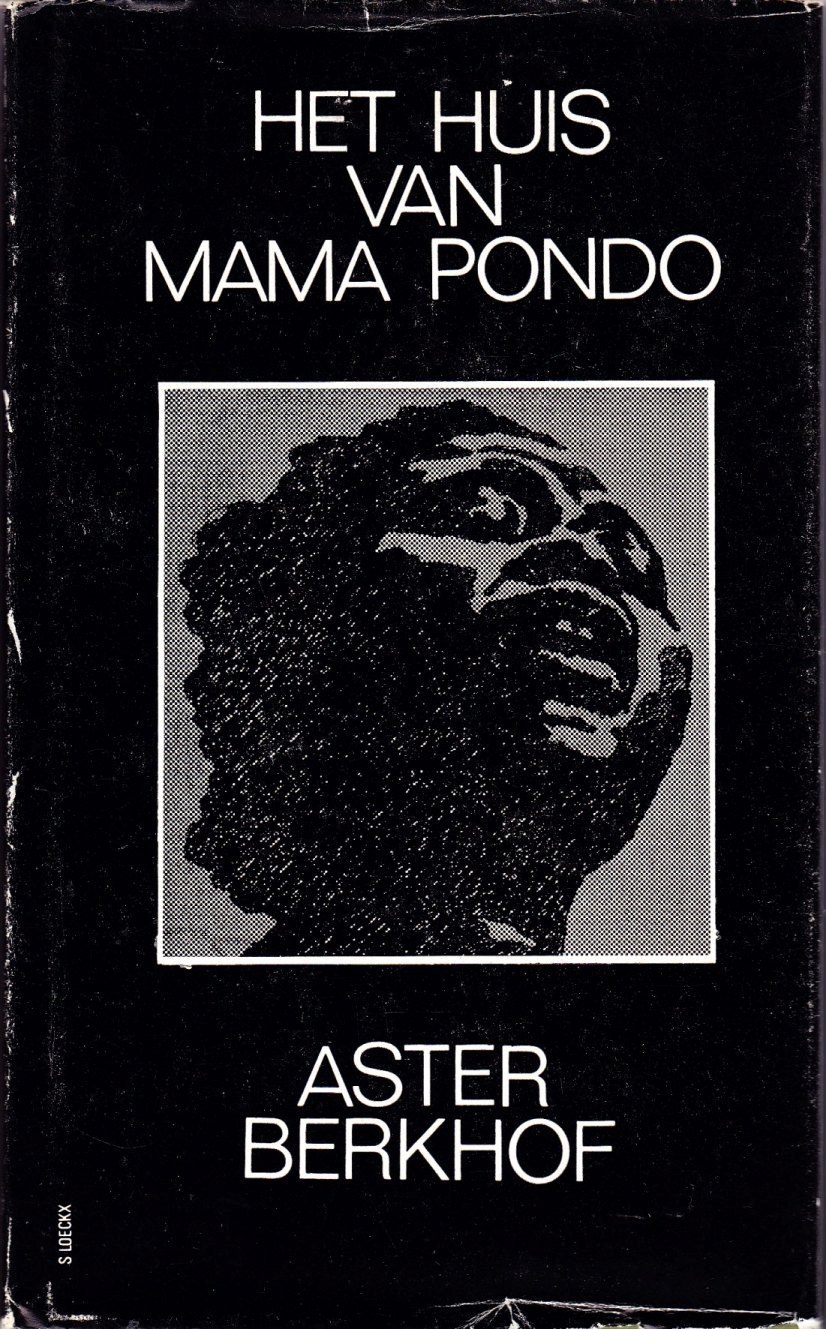

Mama Pondo’s House (1970)

Mama Pondo’s House (1970)Berkhof’s pleas for a broader interpretation of Christianity, anticipating the Second Vatican Council, did not go over well with the Catholic critics back then. Next, in 1970, he published Het huis van Mama Pondo (Mama Pondo’s House), in which he attacks South-Africa’s Apartheid, which is characterized by anything from blatant discrimination to torture and murder, and the dramatic banishment of the black population to the Bantustans. (In 1992, he adds a prologue to the tenth, revised edition, which includes the comment that the white people, in anticipation of the very first general elections, are attempting to manipulate the Zulus and the Inkatha movement, by, for example, quickly pushing through a new constitutional law with guarantees – as it were – for black people.) In Flanders, the novel is heavily criticized by friends of South-Africa, and it is met with accusations of bias and exaggeration; that much suffering in a single black family could never be a truthful representation of reality.

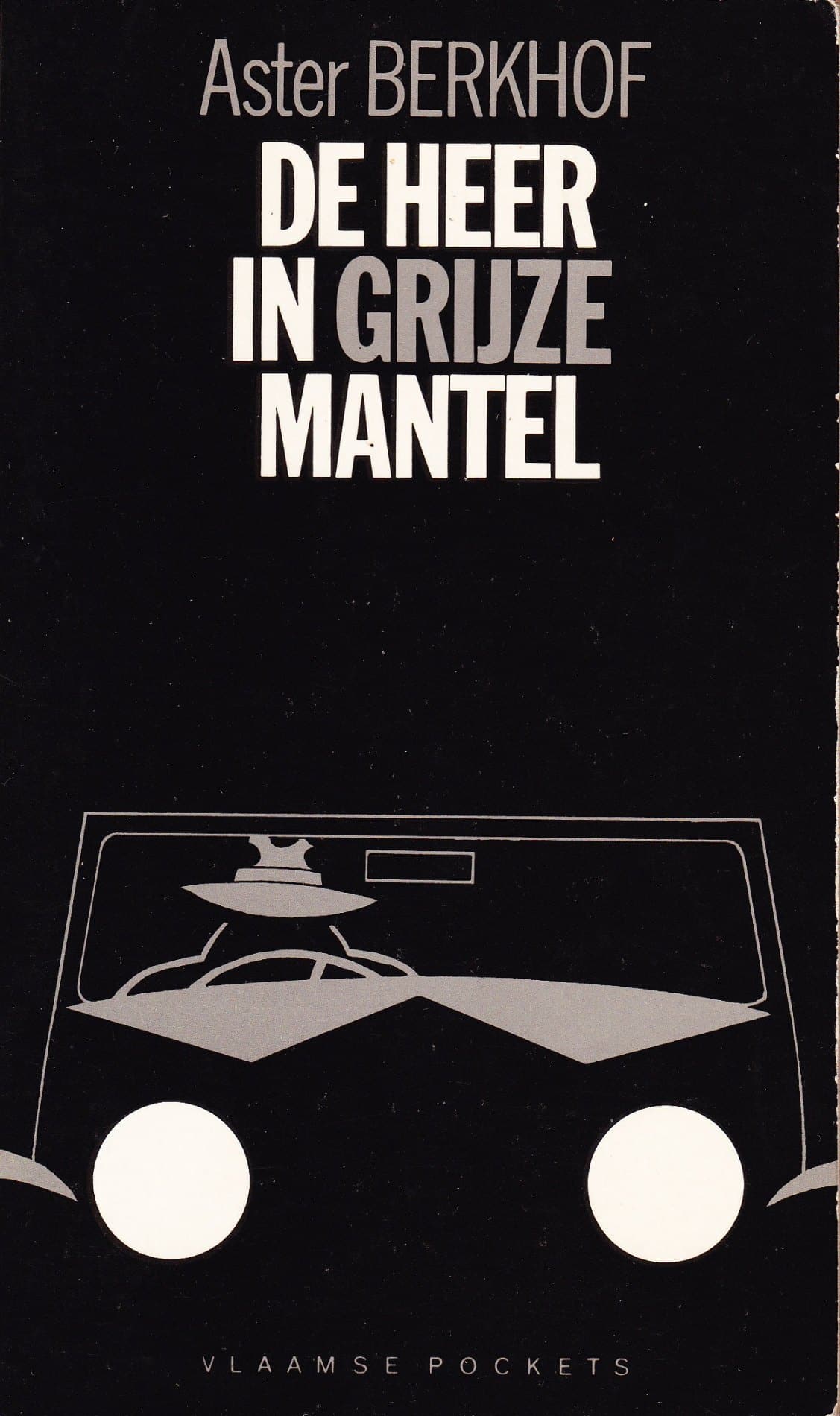

The Gentleman in the Grey Coat, Berkhof's debut novel from 1944

The Gentleman in the Grey Coat, Berkhof's debut novel from 1944For the love of travel

How does Aster Berkhof end up in all of those exotic locations? In the autobiographical story entitled Souvenir, which is part of the Alle verhalen (All Stories, 2009) collection, he discloses that, when he was in primary school, he did not care too much about fairy tales. Instead, he became fascinated with books about adventures, taking place in far-away countries. “I decided I would eventually visit all of those locations.” He studies Germanic Philology, completes his military service in the North of England, and while he is working on his doctoral dissertation, as a way to relax, he decides to devote himself to writing a crime story, De heer in grijze mantel (The Gentleman in the Grey Coat, 1944) and the romantic (two-part, 900-page) Rotsen in de storm (Rocks in the Storm, 1947), which is set in Scotland. Brits studying in Switzerland rave to him about the joy of skiing. Hearing this, he is eager to give it a try as well. “I was bowled over by the beauty and the purity of the grand, white mountain ranges.” Back home, he writes, “even before unpacking my suitcase”, the first pages of Veel geluk, professor (Good Luck, Professor, 1949). That book and that genre will be associated with him for the rest of his life.

Good Luck, Professor (1949)

Good Luck, Professor (1949)He writes at an incredible pace (although he only writes in winter), quite similar to the way he talks – it flows and keeps on flowing. Fluent narratives prove to be his thing, about the adventures of young people, who lead fascinating lives in sophisticated places or in exotic locations none of his readers will ever visit. He is well-liked, a well-liked TV personality, a much sought-after public speaker, an effortless, enthusiastic, captivating conversationalist.

He decides to become a teacher (in grammar schools in both Antwerp and Brussels) and also teaches at the Antwerp Business School. Moreover, he wants to travel. Travelling means the world to him. Each of his travels inspires him to write his young-adult fiction and travel tales, and provides him with ideas for lectures, TV programmes, and, quite frequently, ideas for his novels as well. (He tours South Africa, including the Bantustans, ‘with a lump in my throat’).

Budding talent

Then, in the 1980s, he returns to his own country in his novels, always keeping the rest of the world at the back of his mind. The societal imbalance he notices in this country has an increasingly negative effect on his mood. And, at the same time, he testifies how his own talent is coming into fruition.

In the 1980s, he returns to his own country in his novels, always keeping the rest of the world at the back of his mind

In the above-mentioned trilogy he once again – just like he did in Het huis van Mama Pondo – calls upon a large family (living in his native town of Rijkevorsel), blessed with an unusual number of children, who each represent a ‘problem’. One of the sons, Leo, is forced to become a priest and symbolizes a struggle with faith and doubt. Daughter Valerie leaves her husband and calls into question traditional marriage. Son Hubert marries a woman who is not able to fulfil her conjugal duties, and he takes these sexual issues upon himself. Another son, Paul, follows in his father’s footsteps and acquires his father’s ambition, idealism, but also his opportunistic ways.

Abuse of power

Berkhof makes a number of these topics more explicit in a similar way in his treatment of the sons in Donnadieu (1991). Father Donnadieu, a stockbroker, administrator of mainly church property, acts like a tyrant by forcing his children to reach the top in various disciplines, so he is able to solidify his own power, influence and prestige. His daughter becomes a prioress in a convent, his sons work as a banker, a general, a cardinal, a theologist, a leading magistrate, a successful businessman and even a prime minister.

These occupations involve professional image building and lobbying, mass religious outdoor gatherings, shady press practices, and the unscrupulous elimination of potential rivals. One of the sons becomes a worker-priest somewhere among the poor in Italy, and because of his progressive ideas (e.g. concerning celibacy), his father takes him out. Another son, a journalist, finds himself torn between his loyalty to the mechanics of power his father had installed and his own desire for freedom. In this sense, Donnadieu

deals with the abuse of power, hypocrisy, merciless ruthlessness, opportunism and moral coercion, allegedly for the sake of the Church and our Nation.

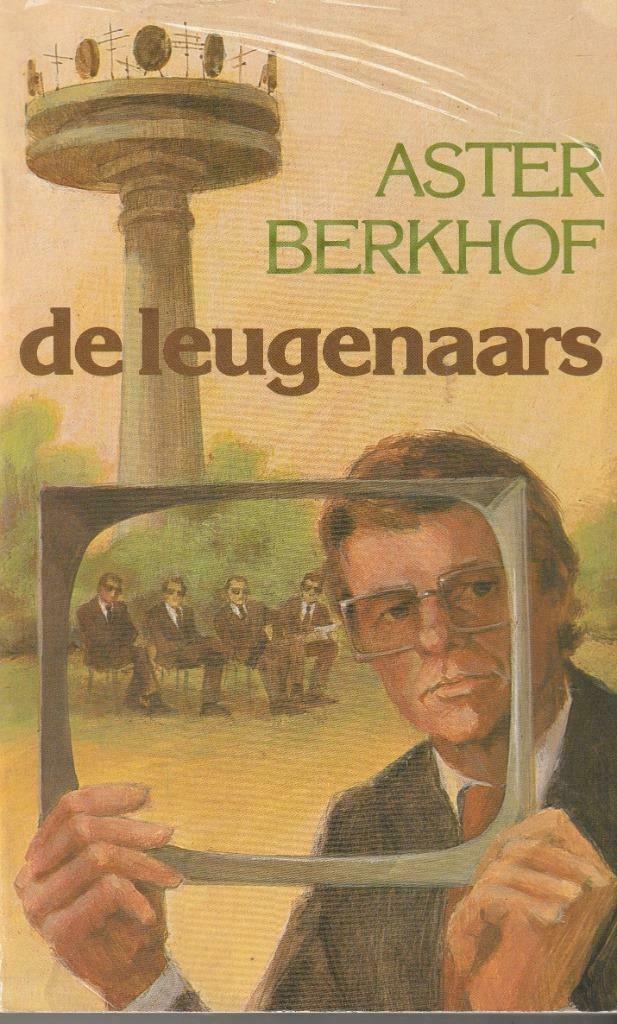

The Liars (1982)

The Liars (1982)From this point onwards, Berkhof’s novels are characterised with a vindictive tenacity, a resolute rejection of all of society’s deformities and excesses, of anything that limits or takes away man’s freedom to enjoy life. Here, women are allowed to take centre stage as well. In the 1984 novel Amanda, which you can read as a supplement to the above-mentioned trilogy, a mother decides to abandon everything and everyone soon after her seventh child’s eighteenth birthday. This perfect wife and ideal mother, who, for years, was an absolute delight around the house, chooses to live her own life and explains her actions to her kids in a letter: a twisted religious morality, a suffocating religious and middle-class hypocrisy.

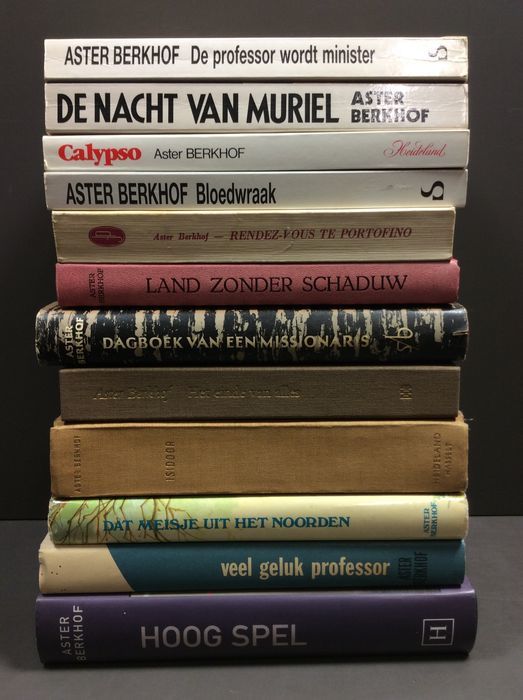

Berkhof continues to fulminate against politicians’ continuous attempts to control Flemish public-service broadcaster BRT (in De leugenaars, The Liars, 1982), against the impact of Roman Catholic fundamentalism (in Octopus Dei, 1992), against the conflict of interest between right-wing politicians and a property developer in the Brussels Northern Quarter in Happy Town (1994), against Islamic fundamentalism (in Met Gods geweld, With God’s Violence, 1996), and so on.

Genuine passion for societal issues

All of these novels, and even his later crime stories in which now invariably social phenomena such as the one mentioned earlier are brought up, demonstrate Berkhof’s honest commitment and deep-rooted moral indignation. They, however, would have gained literary value had they not suffered from an all too simple, hastily drawn-up concept, an all too aggressive plot with a blatantly obvious structure, thus revealing the author’s technical inadequacies. Throughout Aster Berkhof’s career, this particular facet of his oeuvre has affected his potential wider, official recognition. Yet, despite all of this, at least Dagboek van een missionaris, De woedende Christus and the rather surprising Donnadieu can be added to his list of achievements, next to Het huis van Mama Pondo.

In his novels, you can read about the development of the Flemish mind-set during the second half of the twentieth century

Aster Berkhof started off by charming his readers with his smooth, adventurous stories set all over the globe. Then, he disarmed them with his genuine passion for societal issues, which distracted Berkhof’s readership from his occasionally flawed writing technique. In his novels, you can read about the development of the Flemish mind-set during the second half of the twentieth century, from a strict Christian authoritarian conservatism to a more personal, relaxed, lively sovereignty. In his writing, the novelist managed to make this development his own. For all of these reasons, Berkhof should look back on a life (thus far) well spent.