Astrid H. Roemer: ‘Dutch Will Slowly but Surely Disappear From Suriname’

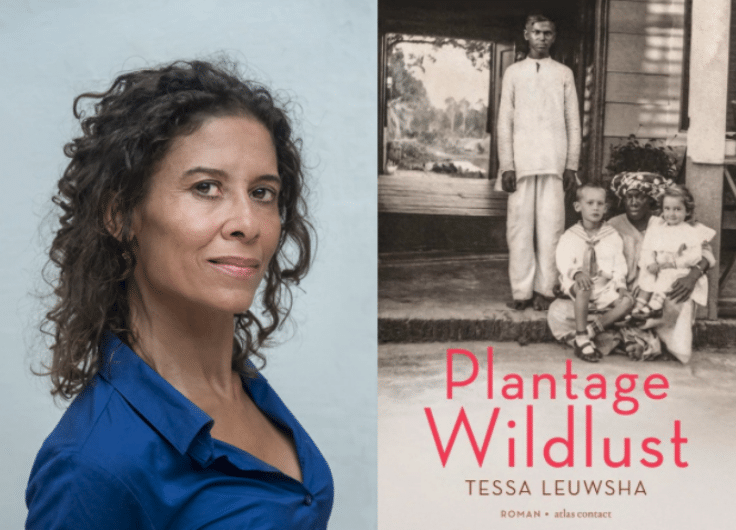

Astrid H. Roemer is the first writer from Suriname, a former Dutch colony in South America, to win the most prestigious Dutch-language literary accolade: The Dutch Literature Prize (Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren). Fellow writer Tessa Leuwsha interviewed her in Paramaribo, where they both live. The Surinamese writer talks about her characters, language, colonialism, and the future of Suriname. ‘I don’t claim the Surinamese region as some sort of national or historical property. Nevertheless, there is nowhere in the world where I’m as content as in my country of birth.’

‘With her novels, plays and poems Astrid H. Roemer occupies a unique position in the landscape of Dutch-language literature.’ This is how the jury justified awarding the Dutch Literature Prize (the Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren, worth 40,000 euros) to Astrid Heligonda Roemer (born in 1947 in Paramaribo). ‘Her work is unconventional, poetic and authentic. Roemer succeeds in connecting major themes from recent history, such as corruption, tension, guilt, colonisation and decolonisation with minor historical themes, stories on a human scale,’ the jury report continued.

Astrid H. Roemer

Astrid H. Roemer© Sirano Zalman

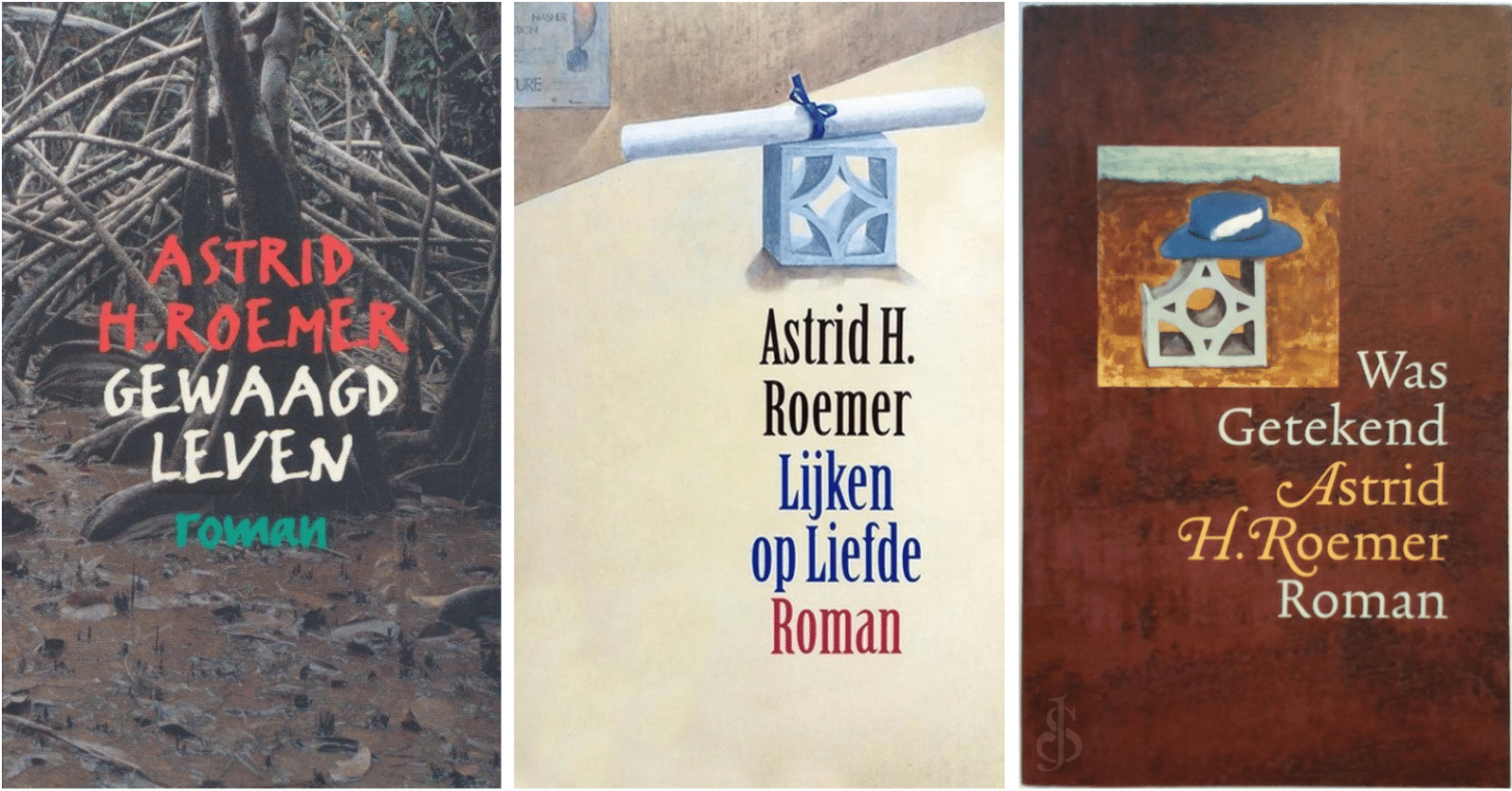

Roemer debuted in 1970 under the pen name Zamani with the poetry collection Sasa: mijn actuele zijn (Sasa: My present being) and has since published further poetry as well as novels and plays. Roemer’s narrative prose forms the most important part of her oeuvre, including the book with which she made her breakthrough in the Netherlands in 1982: Over de gekte van een vrouw. Een fragmentarische roman (On a Woman’s Madness: A Fragmentary Novel). The trilogy Gewaagd leven (Daring Life, 1996), Lijken op liefde (Looks Like Love, 1997) and Was getekend (Signed, 1998) – about Suriname in the second half of the twentieth century, in particular after the coup of Dési Bouterse in 1980 – is seen as her magnum opus.

After the year 2000 Roemer disappeared from public life for a long period, spending time living in the Netherlands, Rome, Paramaribo, Edinburgh and Ghent, among other locations. Only in 2016 did she reappear at literary and other events. That year she also received the P.C. Hooft Prize for her entire oeuvre. ‘Political engagement and literary experiment go hand-in-hand for Roemer,’ the jury wrote at the time. ‘According to the jury’s verdict, that results in novels which are sharp, relevant interventions in the public debate and at the same time complex literary representations of the history of Suriname.’

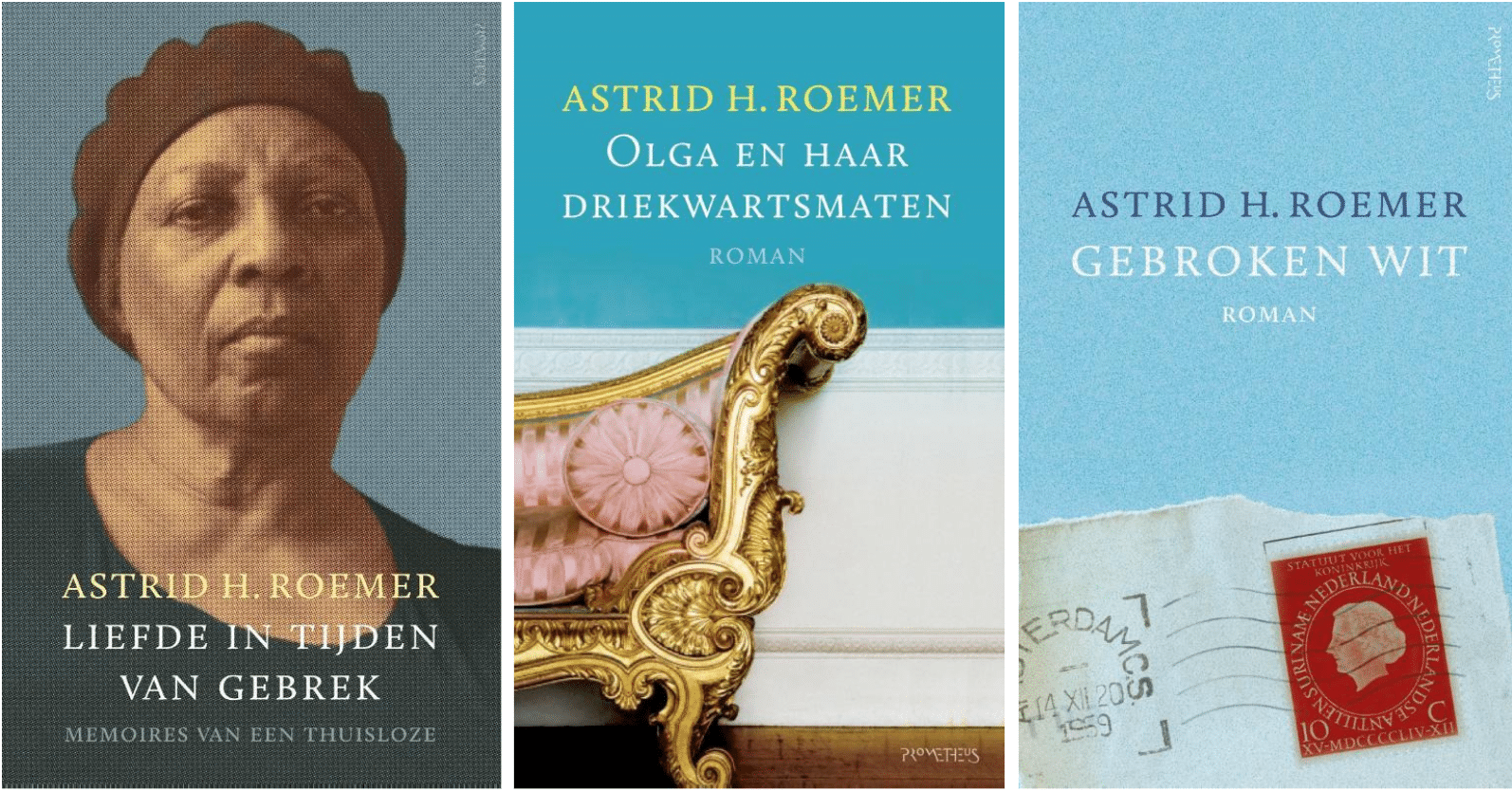

Since being awarded the P.C. Hooft Prize, she has published Liefde in tijden van gebrek: memoires van een thuisloze (Life in Times of Shortage: Reminiscences of a Homeless Person, 2016) and the novels Olga en haar driekwartsmaten (Olga and her Three-Quarter-Measures, 2017) and Gebroken wit (Off-White, 2019). For autumn 2021 she has scheduled the novel DealersDochter (Dealer’sDaughter), in which ‘a country of birth turns out to be no more than a geographical region that can never be known, just like blood relationships,’ as the publisher’s catalogue states. That sentence makes it clear that once again her new novel addresses migration and family, themes which always place a major role in her work, alongside sexual orientation, racism and emancipation.

Writer and journalist Tessa Leuwsha wanted to seek out Roemer in Paramaribo, where she herself lives and where Roemer returned after the death of her mother in 2019. Due to the worrying COVID-19 situation in Suriname, in the end, it was a written conversation. Leuwsha turned the disadvantage of distance into an advantage, revealing to readers two writers communicating as if in an exchange of letters. In writing, the medium with which they are familiar. In her answers, Roemer’s style is clearly observable in the considered choice of words and in the unusual use of capital letters and punctuation.

TESSA LEUWSHA: Congratulations on the Dutch Literature Prize. How does it feel to receive this recognition?

ASTRID H. ROEMER: ‘I’m head-over-heels with joy. Thank you for the congratulations.’

More and more readers are getting to know your work. What should they know about you in order to understand you and your work?

‘I take great pleasure in reading novels by authors I know nothing about and don’t feel the slightest need to know anything about their personal lives. Every novel is an independent entity and readers can develop a relationship with it. And as an author I’m of no importance in that process, I hope.’

Really? After all, you are the maker of the work. Isn’t there a great deal of you in it?

‘I’m certainly entirely the maker of my novels but whether much of my personal experience is contained within them, I’m not so sure. In fact, I doubt it. What I know is that my work is authentic but that is a matter of professional skill. You really don’t need to know me to understand one of my novels.’

'You really don’t need to know me to understand one of my novels.’

Your prose is characterised by an unconventional, poetic style that seems to arise from a stream of consciousness that is sensory in nature and uses unconventional punctuation. In this respect, you have been compared with Virginia Woolf. How important is that style to you?

‘I have been compared with Woolf, Marcel Proust, Gabriel García Márquez and in particular with Louis Couperus from The Hague. Black reviewers compare me with Alice Walker and Toni Morrison. My style varies from one novel to another. It is within the context of new work that my style has developed as a placenta that grows with the child after each conception and is always different. That’s a good comparison, isn’t it? It feels good to me. I’m surprised by the connotations and interpretations of readers and reviewers. It’s nice to resemble other good novelists.’

Definitely a good comparison! I recognise what you say about style, although many writers see it as like handwriting, unchanging. How about the themes of your work? How have they evolved?

‘My novels aren’t thematic. My characters live a full life in which things happen which might perhaps appear thematic but which point to the habitat and the Zeitgeist in which they operate. I immerse myself deeply in living conditions on all levels. My characters are generally multi-ethnic and that quality certainly generates diverse confrontations which are constantly in motion for me. In fact the same goes for gender issues, to name one theme after all.’

In Gebroken wit (Off-White), your latest novel, the characters of the extended Vanta family live in Paramaribo. You call the city a coastal city and describe it remotely, life is centred around the family. You’ve been living back in Suriname again for some time yourself. How essential is the city of Paramaribo to you? Do you feel Surinamese, Dutch, a world citizen? How boundaried is your literature?

‘Paramaribo is my birthplace and to me, it represents everything we call Suriname. As I child I regularly travelled on holiday by boat deep inland with the family of my mother’s sister, my godmother. Paramaribo resonates intensely in my novels and also in the way I structure my life and how I choose my friends. Paramaribo is not only physically but also mentally a reality I can always fall back on in times of happiness or discomfort. I love my birthplace. The coastal city of my dear mother, knowing that there is a hinterland of Amazon rainforest vibrating along with it. In that sense, I primarily feel that I’m Astrid Heligonda Roemer and probably primarily an inhabitant of the earth. I couldn’t sincerely call myself a world citizen as there is so much of the human world that I don’t or barely know. My work is subject to a linguistic border but on the interpersonal level it is boundless.’

'My work is subject to a linguistic border but on the interpersonal level it is boundless.’

What’s it like to be inspired by your country of birth where you have lived intermittently and long been absent? Is it alienating to look at it from that position, to have Suriname in your hands as material? Is it a different country, is it your country?

‘I don’t claim the Surinamese region as a kind of national or historical property. Nevertheless, there is nowhere in the world where I’m as content as in my country of birth. I’m fond of Europe and European things and the pretensions of the United States fascinate me and oriental countries have my admiration but Suriname….poverty-stricken and penniless… a piece of rainforest on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean….that hemmed-in region…THAT’s what I am, as Bea Vianen once wrote SARNAMI HAI (‘Suriname, I am’, TL) or something along those lines. But don’t ask me to operationalise “who I am” because I can’t!’

How do other countries you’ve lived in, such as the Netherlands, Belgium and Scotland, inspire you?

‘Everything inspires me. Everything and everyone touches me. But it doesn’t become apparent until I write. The intellectual climate in the countries you mention keeps my mind clear.’

Your work places women in the foreground. They are powerfully present, even in their uncertainties. Men, by contrast, are in the background and seem to live their lives more by instinct than by intellect. Is that the way you really see man-woman relationships?

‘Really much of my work is about the space which diverse women receive and often take in order to exist. I don’t think that we humans live instinctively. We are genuinely thinking creatures. And both the women and the men in my novels and stories are too. But I enter the area of INTIMACY, where irrationality trumps all. I try to articulate something that cannot be pinned down at all. And my perspective is primarily that of a woman like myself: with a broad orientation towards all sorts of things BUT in any case a woman. I love the men in my novels and the way they struggle through their existence at the side of the women they attempt to love.’

'Much of my work is about the space which diverse women receive and often take in order to exist'

When reading your earlier novels, such as Over de gekte van een vrouw (On a Woman’s Madness) and Een naam voor de liefde (A Name for Love), the term realistic feminism occurred to me. Female characters are aware of their limitations in their relationships but only succeed in ridding themselves of them to a certain extent. Incest, sexual assault, unwanted pregnancies, abortion: it all happens, they seem inevitable. Yet the women remain standing. What is the reality in which you reflect the experiences of your characters?

‘I don’t think any reality exists in which the events you mention don’t happen. I’d never seen snow until I was twenty but I never doubted its existence. Nothing human can be unfamiliar to me and the older I get the less I am inclined to look the other way. I feel connected with characters who fight their way to freedom, thus developing new and better models of society and subcultures that distance themselves from traditional and often patriarchal violence.’

Do you feel you fought your own way to freedom?

‘I haven’t had to fight my way to freedom because I’ve never had relationships with people who could cage me. Not in business, nor romantically, nor in friendship. I was twenty when I left my parental nest for good and went to live in the Netherlands in complete agreement with what my mother wanted. Not opting for a traditional life as a woman was a free choice that kept me independent in a relational sense. To be honest, I have sometimes had to fight my way free of my own impulses with respect to loving a person who was damaging to my wellbeing. My family and friends, however, are like buoys at sea: they limit my independence emotionally and spatially: I can’t go adrift. That’s good. I love my nearest blood relatives.’

'Not opting for a traditional life as a woman was a free choice that kept me independent in a relational sense'

In Gebroken wit (Off-White) this colour recurs in orgeade, the Surinamese almond drink, the colour of objects and in the skin tone of characters who carry white and black within them and thus express the connection between Suriname and their former motherland the Netherlands. The novel is about family structure within the often fragmented family life of Suriname, where it is primarily women who shape that family life when fathers fail. Do you see that structure as a consequence of colonialism, or slavery and contract work that led to family breakdown? To what extent do the consequences of that live on in your work and in yourself?

‘All over the world, it is mainly women who keep the family unit and even the extended family together. Men are well practised at guarding the structures. Fragmented families don’t exist: to me what exist are diverse family forms. And that’s good. All family shapes have weaknesses and strengths and it is up to us to support them in word and deed and also with financial means to prevent things from getting out of hand. Each kind of family is valuable and cohesive. Only in the last one hundred years, after hundreds of years of oppression and exploitation of flora, fauna and slave labour, has Suriname been in the process of awakening from the bewilderment of not being DUTCH-EUROPEAN but SOUTH AMERICAN and integrating into and onto the continent will take an extremely long time but will bring surprises. The diverse family shapes which have developed in the context of long-term slavery and intense colonialism are valuable and fit precisely into our multi-ethnic society. I don’t have any destructive interpretations or unpleasant personal experiences to add. Surinamers form the youngest nation in the world and needn’t make the mistakes that currently plague the western nuclear family: too many divorces, excessive addictions and endless cases of cruel domestic violence. I believe we humans are searching for a way to set up our society with safe spaces for women and their children and their men, for young people to meet and get to know one another; and that search goes on worldwide with falling and getting up again and with a great deal of violence against women and their children. COME WHAT MAY we must always and everywhere remain alert and offer help if needed.’

Will Suriname have to give up the Dutch language for South American integration?

‘Of course, Dutch will slowly but surely disappear. What remains of it at the moment, on examination, is good for nothing. A language should be able to bring a person and a group progress and that’s not going to happen with Dutch. Even in the Netherlands people inevitably pick English as a second language.’

What are your hopes for Suriname?

‘Ach. I fear that the Suriname I know will gradually disappear into the past. I also fear that ethnic prejudices and interests, corrosive poverty and other disadvantages will lead to mass conflict. I want young people to have a good and happy existence in their own territory but I fear that they will continue to seek salvation elsewhere. My birth country still has far too little to offer young people from an intellectual perspective. Perhaps they can find it elsewhere, in another South American country. But where?! In the distant future, I see nothing more of the Suriname that we still recognise to some extent now. I hope I turn out to be wrong. The region will, in any case, survive as magnificent Amazon rainforest.’

'In the distant future, I see nothing more of the Suriname that we still recognise to some extent now'

You left your family in Suriname to study and work abroad. Suriname has a small population and a village feel. You broke with the Surinamese way of life by going through life as a writer more or less as a loner; you even spent some time living in seclusion on the Scottish island of Skye. Has that individuality had repercussions for your work?

‘Everyone is alone. I could have chosen motherhood and formed a beautiful family instead of writing beautiful novels. I never broke with the Surinamese way of life. I also don’t feel like a loner although I take pleasure in living my life completely alone. I need a certain habitat for my work and I seek that out. Often I construct a workable habitat myself. My personality has been moulded by writing. That’s good. She who walks through the rain will get wet.’

'I never broke with the Surinamese way of life'

When do you walk in the sun? That is to say, when are you most content? Is it when you write?

‘Strange question Tessa Leuwsha! I’m in the sun the moment I wake up in the morning. That light, that wonderful light that banishes darkness and offers me so much warmth and so many forms of life. In a literal sense, I no longer walk in the sun. Head always covered. Sunglasses always on. Blinds always down in my house. But I worship the sun. Nevertheless, weather conditions are like natural sentiments that get me writing. I have no preferences among them. I undergo the hours of Amazon rain showers with intense pleasure. Everything is good as long as I can remain safely indoors. And write…’

You write in Dutch. How do you relate to that language and to the variant you know from childhood, Surinamese Dutch? Do other languages reverberate through your mind as you write, such as Suriname’s lingua franca, Sranantongo?

‘I write in Dutch and that language is my mother tongue. Surinamese Dutch can join in when it’s appropriate and makes sense. Our immediate and extended family values correct Dutch. We weren’t forbidden from using Sranantongo: Sranan was used in contact with others who spoke no Dutch. And that’s still the case. Never ever will we address each other in Sranantongo in a family context. Sranantongo is my street language. Now that I’m older and my dear mother is no longer alive I increasingly want to speak Sranan with everyone I meet. A form of naughtiness perhaps. Perhaps simply the nature of the beast to be a little mischievous…’

'I write in Dutch and that language is my mother tongue. Surinamese Dutch can join in when it’s appropriate and makes sense'

At home, my father wouldn’t let me speak Sranantongo either. Don’t you see that as another expression of the knock-on effect of colonialism? The rejection of one’s own national language?

‘To me, Sranantongo is not the national language of Surinamers but a lingua franca. It’s crazy but true: Dutch is and for the moment remains our national language however badly we speak it with the excuse of speaking Surinamese Dutch. Sranan makes for wonderful street language, more of a men’s language than a language for women. I feel tough when I speak Sranan. Your dad was right.’

Gebroken wit (Off-White) is set in the past, in a Suriname in which someone listens to a radio play and where an international telephone call is something one has to apply for. How do you feel about the present in Suriname?

‘No idea how I currently feel about Suriname. I’m grieving for a woman who was lovingly close to me for more than seventy years as my very own mother. I didn’t know that the death of a parent can punch such a hole in the lives of the bereaved. I am confronted with all the mistakes I’ve made. That’s good. Gebroken wit (Off-White) is set simultaneously in the present and the past. Hundreds of people correct their behaviour and adjust their relationships after reading my novel Gebroken wit (Off-White) and the same thing happened with my other work. I’m happy to be partially responsible for better behaviour and more loving relationships between all kinds of people. I’m very much a HERE AND NOW PERSON.’

You have a new novel coming out this autumn, DealersDochter (Dealer’sDaughter). What’s that novel about? What can we expect from it?

‘Better to have no expectations.’

Astrid H. Roemer’s work is published by Prometheus.

Translated work of Roemer can be found in the database

of Flanders Literature and Dutch Foundation for Literature.