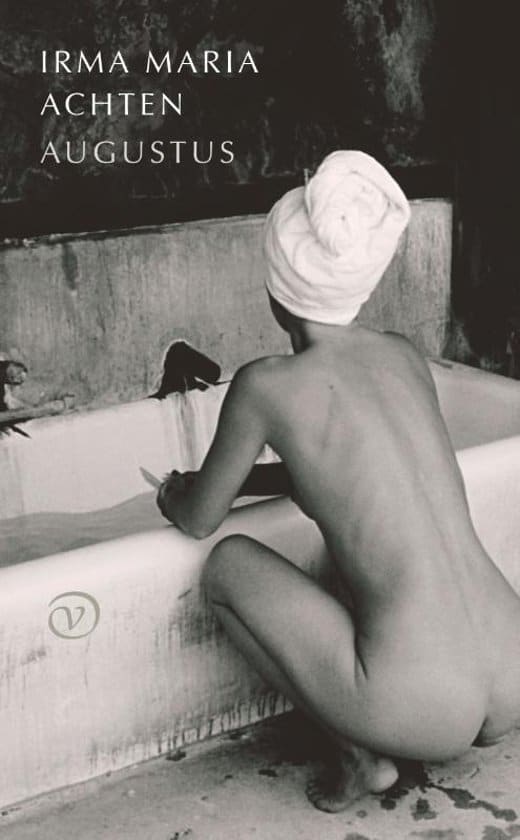

‘Augustus’ by Irma Maria Achten: Torn Between Passion and Longing

Augustus (August) by Irma Maria Achten (b. 1956) is a sensual debut novel about improbable love, in which passion, a longing for death and family secrets play an important role.

Romeo Montague met his Juliet at a party he was forbidden from attending. At one point it seemed he might even be murdered by a tiresome member of the rival Capulet family. But later that same evening, Romeo was declaring his love to Juliet, who sighed back at him longingly, and already the next day the young couple were forging a plan to get married. Love at first sight has rarely evolved as swiftly as in Shakespeare.

Irma Maria Achten

Irma Maria AchtenAlthough the beginning of Augustus, the debut novel by Irma Maria Achten, comes close. Sixteen-year-old David is lying on the bottom of the Vecht River doing stamina training, when his breathing exercises are disrupted by a loud bang, and a powerful wave drags him off like a twig. He tries to save the couple in the sinking car, but he does not succeed straight away. The woman in particular refuses help. ‘She lifted her hand towards me and what should have been a slap in the face through the resistance of the water turned into a halfway caress.’ It is an omen: the couple is saved, and the following morning David writes in his notebook: I found her.

Although it is not very long before his love gets a name. Her name is Mercè, the young Chilean wife of a well-known art historian. Together the couple had enjoyed some fame on TV talk shows, but that was when David still had to go to bed on time. All guys used to be in love with her, his mother assures him, and now he is the hero who saved her from drowning.

Unaware of their teenage son’s intense feelings, David’s parents invite Mercè and her husband Jan Willem to dinner, and later even on holiday at their home in Antibes. The inevitable happens: the warm-hearted Mercè succumbs to David’s blank slate and perpetual passes, and together they discover true love.

Achten’s writing is spot-on, with a sense of humour, and is at times very sensual, even arousing

Using short fragments, Achten tells the story of the love between Mercè and David, but also of the unravelling marriage of Jan Willem and Mercè, and the background of her life in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship. That background is obscure, even for Mercè, and it takes a trip to her home country to discover the truth. Those three stories are patiently woven together. The more invested you are in the love story, the more you come to understand the failed marriage. And the more you learn about Mercè’s childhood, the better you understand her dubious love life, and her melancholy longing for death.

For Achten, who is well known as a filmmaker, this novel is a debut, but she gained writing experience as a screenwriter and librettist. You can see that in the fragmentary construction of Augustus, which almost begs to be filmed. But fragmentary does not mean cut up or disjointed. This story propels itself forward; Achten’s writing is spot-on, with a sense of humour, and is at times very sensual, even arousing. She changes perspective at the right moment, telling the story from David’s point of view, then letting Mercè speak. In this way, you see how the pace of their lives is not always parallel, and how difficult it is for lovers to really understand, let alone truly know, one another.

Meanwhile, you feel the burning desire between David and Mercè, you believe in their love for each other. The moments in which Achten describes their passionate lovemaking are among the book’s most beautiful passages. Writing (and reading) about sex is often a tricky business. It can quickly feel too flat, or too sugar-coated. Not so with Achten, who writes about sex in a very natural way.

It does not always end well for passionate, quickfire love. Once the sparks have settled, often all that is left are a few smouldering embers. That or former lovers hatefully hound each other away. It is not as melodramatic here, but neither does the story have a “they lived happily ever after” ending. There is room for a tear, but also for a hopeful smile. Here too, the book is perfectly balanced.

Excerpt from ‘Augustus', as translated by Paul Vincent

Excerpt 1 – pp. 72-73

‘Don’t you have any friends of your own age?’ I ask David.

We are in the Rechtboomsloot, it is almost dark, we are sitting on the bed, eating some of those exquisite lemon tarts that David loves so much and that you can only get from Holtkamp.

‘Bernt, I sometimes do homework with him, but he’s a bit older, he’s been kept down a class twice.’

‘And girls?’

‘Whoever wants a young girl.’

He turns towards me, on his side. Those dark serious eyes of his, they draw me irresistibly towards him.

‘Did you see my Granny during that meal at our place, my mother’s mother?’

‘Not really.’

‘As a child I always crawled onto her lap. I loved touching that loose skin on her upper arms. Perhaps it was my first erotic experience.’

‘You’re kidding.’

‘It’s true,’ he says.

He strokes my upper arm.

‘Hurry up and get old,’ he says.

David bends forward, puts his saucer on the floor and pulls his satchel towards him. That back of his, I’d like to see a photo of him as a toddler, I can’t imagine that he has ever been anything but broad-shouldered. He folds open the exercise book he has picked out with the knuckle of his index finger.

‘Here we go,’ he says.

To begin with his voice has a rather solemn tone, but gradually it becomes more real. For his subject he hasn’t ventured very far afield. It’s about a boy who starts an affair with an older woman. I find the love scene quite explicit, but secretly also a relief. He closes the exercise book.

‘It isn’t finished yet,’ he says.

‘I should hope not.’

A crease appears between his dark eyebrows. Does he know how much I love him?

‘When I have thirteen of them, I’ll send them to a publisher.’

‘Why not eleven or seventeen?’

‘Thirteen.’

His determination, it’s the same with everything, is impressive.

Excerpt 2 – pp. 139-140

Mercè had cooked. She waited for me at a set table ‘in the first row’, as she called the terrace at Nysi on the edge of the cliff, as close as possible to the sea. I came through the garden and studied her from a distance. It was as if I were seeing her for the first time. She was lost in thought, her face was leaning on her hand and had a calm expression. What was she thinking about, I wondered. They seemed to be pleasant thoughts. They say that there are lovers who take possession of each other’s interior life. But Mercè would not be possessed, she remained unfathomable. She turned her face towards me, almost embarrassed, apologetic.

Mercè had many different moods. It was as if, as the day progressed, she changed specific gravity, and became lighter. She thought I loved her most in the evening, but that wasn’t true. I was in awe of her nights, the fact that she experienced so much, I felt fatuous beside her. I woke up feeling fresh, jumped out of bed and had no notion of where I had spent the night. If I remembered three or four dreams a year that was a lot. For me they were rare, I cherished them and had the feeling that by remembering my dreams I was living more deeply and on several levels. Mercè thought I was romanticising the dream world.

‘You take my dreams,’ she once said,’ so I can get on with my life.’ Her inner life was much richer than mine, more complex too.

Mist was rising from the sea. I sat down at table with her. She had made stuffed aubergines. It was one of those evenings when I loved every fibre of her being, her silence, her voice, the angle of her head, the reflective glance with which she looked away, her delightful smile.

It was as if I were filming her and storing her in my memory frame by frame.

We discussed everyday things, the garden, what we were going to plant, what we would prune. Every sigh, every movement was perfect. Without giving it a name, we both knew that this was one of those special evenings when all our senses could cope and life was able to pour its beauty into us unfiltered. We walked to the house hand in hand, aware that we were leaving behind something that would never repeat itself in this way.

Irma Maria Achten, Augustus,

Van Oorschot, Amsterdam, 2019, 256 pp.