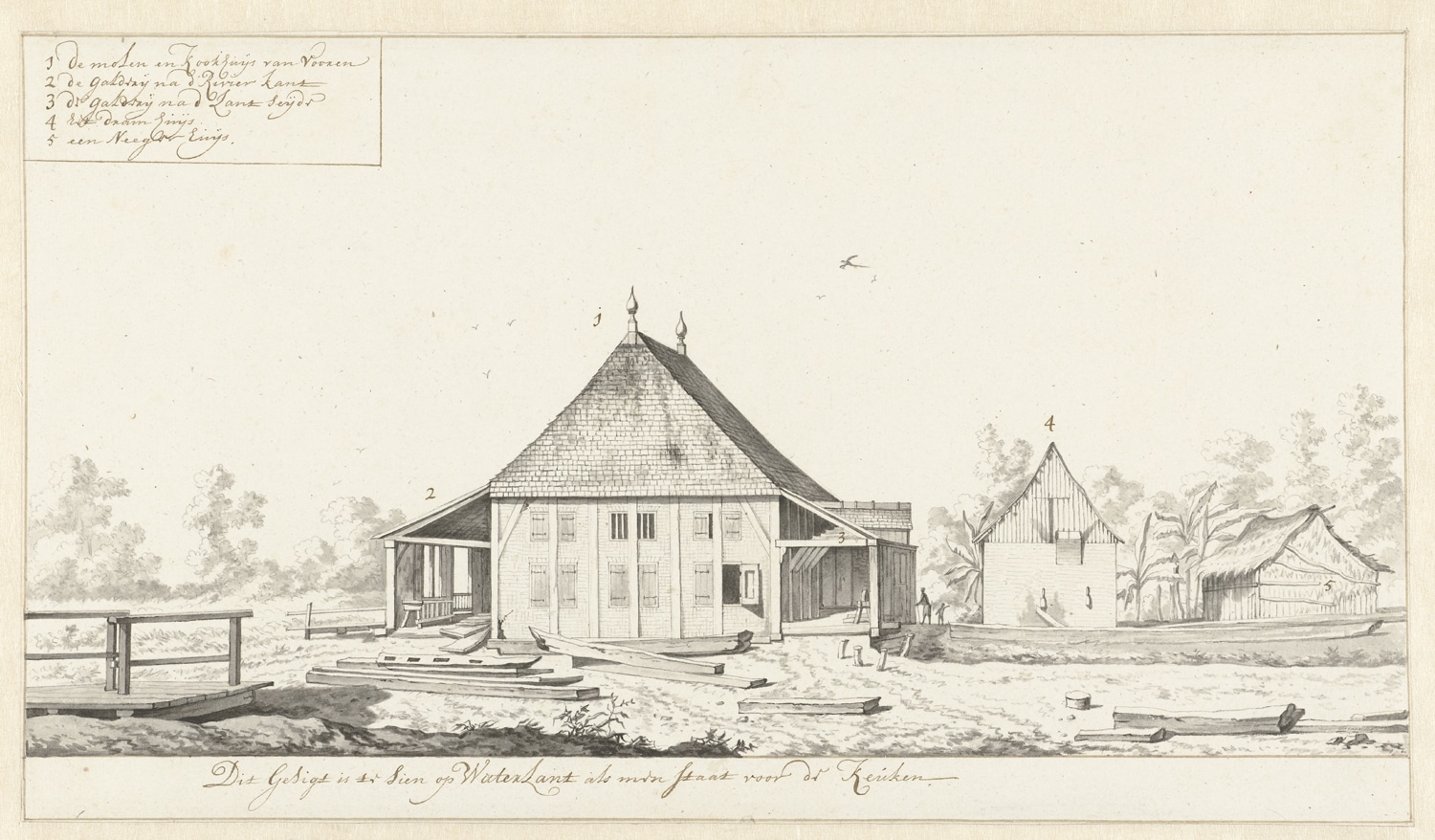

Eighteen young Flemish and Dutch authors give a voice to an artefact from the Slavery exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. Bart Decroos wrote a short story inspired by a 1708 drawing by Dirk Valkenburg, entitled ‘View of a Mill and Cook-house on a Plantation in Surinam’.

Dirk Valkenburg, View of a Mill and Cook-house on a Plantation in Surinam, 1708

Dirk Valkenburg, View of a Mill and Cook-house on a Plantation in Surinam, 1708© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The Idyll

To the viewer looking for human figures, for the men and women who must have populated this scene, I have little to offer. Not that it was my choice, but I cannot show you much more than a few faint figures hidden between the water mill, the cook-house and one of the nearby huts, against the backdrop of the Surinamese landscape. Why the painter covered my surface with only a desolate scene, I cannot tell you either. All I remember about him are the sweaty hands clutching my skin, while scratchy strokes of the pen filled me with ink.

If the painter had positioned himself a little closer to the building, he might have been able to draw some detail in the open window. A machete on the wall, hanging from two rusty nails in the wood. Likewise, he might have depicted the rotating iron rollers which, with creaking cogwheels driven by the spring tide of the Suriname River, squeezed the stalks of cane sugar. And he might even have given us a glimpse of the men who were required to feed the rollers with bundles of cane, day in, day out, day and night.

Had he stood just a little closer, he could have seen exactly what happened. That it must have been an error of judgement or carelessness, caused by fatigue or exhaustion, that prompted one of the sweating men to extend his arm too far. And that the rollers did not discriminate between a cane stalk and a human hand. He would have witnessed the watermill’s logic, which left the next in line no choice but to snatch that machete off the two rusty nails and free the body from the arm, which by then had largely disappeared between the rollers.

But the painter chose to keep his distance.

And from that distance the bright sunlight must have obscured his view of the interior, forcing him to fill the open window with a thin layer of dark ink. And the entire incident must have passed him by, or else he would not have annotated me with a purely descriptive caption, language that falls hopelessly short in telling the story that my surface lacks.

Or perhaps he did not arrive until later. Once the watermill had been stopped and the fires in the cook-house extinguished. Perhaps he did not arrive until the view of the plantation satisfied the conventions of his craft, which sought to immortalise something of beauty on my skin. While I may lack human figures, I do show the flight of a solitary macaw across the emptiness of the sky. With hindsight, from a distance, the plantation looks peaceful indeed, almost idyllic.