Being a Lesbian Was a Dangerous Business in the Southern Netherlands

Women who liked women were punished more severely in the Southern Netherlands than elsewhere in Europe during the late Middle Ages and early modern times. Historian Jonas Roelens has discovered that between 1400 and 1550, 25 female sodomites were persecuted. This figure is exceptionally high compared to the number of prosecutions in other countries over the same period and, paradoxically, has to do with the privileged position of women in the Low Countries.

The idea that two women could have satisfying sex with each other without the intervention of a man was a particularly alienating idea in the mind of the average person in the Middle Ages and early modern period. People held a phallocentric view, meaning that penetration was a requirement before any conversation about sex could take place. Men could choose to have “natural” sex by penetrating women or “unnatural” sex by penetrating other men; but penetration was the key point.

Moreover, our modern notion of sexual orientation was absent at the time. With the exception of a few, rare medical texts that sought a physical origin for homoerotic desires, the prevailing opinion was that sexuality was a matter of individual choice.

Joachim Beuckelaer, The Four Elements: Earth, 1569

Joachim Beuckelaer, The Four Elements: Earth, 1569© British Museum, London

Without penises, women implicitly had fewer options. Once in a while warnings were given about so-called ‘tribades’, or women with extremely large clitorises that could penetrate other women. This was especially the case in the sixteenth century, when increasing anatomical research sparked a scientific debate among physicians about whether or not the clitoris existed as part of the female genital tract. Despite this debate, sexual acts between people of the same sex were considered primarily as something done by men.

Male sodomites more numerous

What we identify as homosexuality today used to be called sodomy and it was both a mortal sin and a severely persecuted crime. The term sodomy, which is derived from the Old Testament story of Sodom and Gomorrah, two cities where the male inhabitants brought the wrath of God upon themselves by having unnatural sex with each other, covered a range of non-procreative sexual acts, including masturbation, bestiality and heterosexual anal intercourse but, above all, homoerotic acts between men.

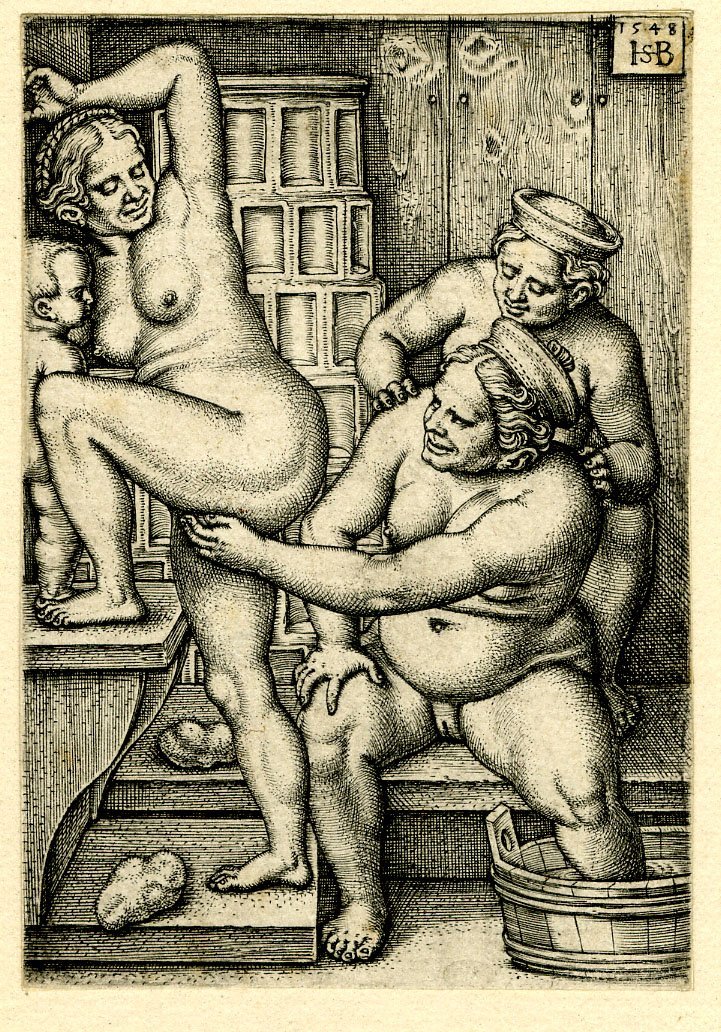

Hans Sebald Beham, Three women in a bathhouse, 1548

Hans Sebald Beham, Three women in a bathhouse, 1548© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Following this Biblical example, many theologians condemned these unnatural acts. Within the phallocentric mindset, it is not surprising that the majority of these authors focused exclusively on male sodomites. This lack of interest in female sodomy is also reflected in medieval law. Only in exceptional cases were women mentioned in civic or royal ordinances on sodomy.

As a result, the number of women convicted of sodomy is dwarfed by the number of men accused of unnatural sexual practices. Even in cities with active persecution policies, such as Florence and Venice, we do not find female sodomites in the source materials. In other regions, such as France, the Iberian Peninsula and some German cities, there were only isolated cases.

The low numbers imply that female sodomy rarely surfaced, though it is also possible that the authorities may have used veiled references specifically in order to keep such incidents under the radar. Since women were assumed to be more curious and insatiable, providing any information about female sodomy had to be avoided at all times, even in the form of announcing a public execution. The risk that voluptuous women would become intrigued by this and start practising sodomy themselves was too great.

Less timidity in the Southern Netherlands

The low persecution rates and desire for discretion were not apparent in the Southern Netherlands during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Between 1400 and 1550, 25 women in that region were accused of sodomy. Thirteen of these were prosecuted in Bruges and five in Ghent. In the fourteenth century, Ghent executed eight women for sodomy. Three women had to answer for sodomy in Brussels, two in Mechelen and one each in Leuven and Ypres. Twenty-five out of a total of 326 allegations of sodomy between 1400 and 1550 means that 7.66 percent of the cases in the Southern Netherlands concerned women: a figure not found anywhere else in Western Europe.

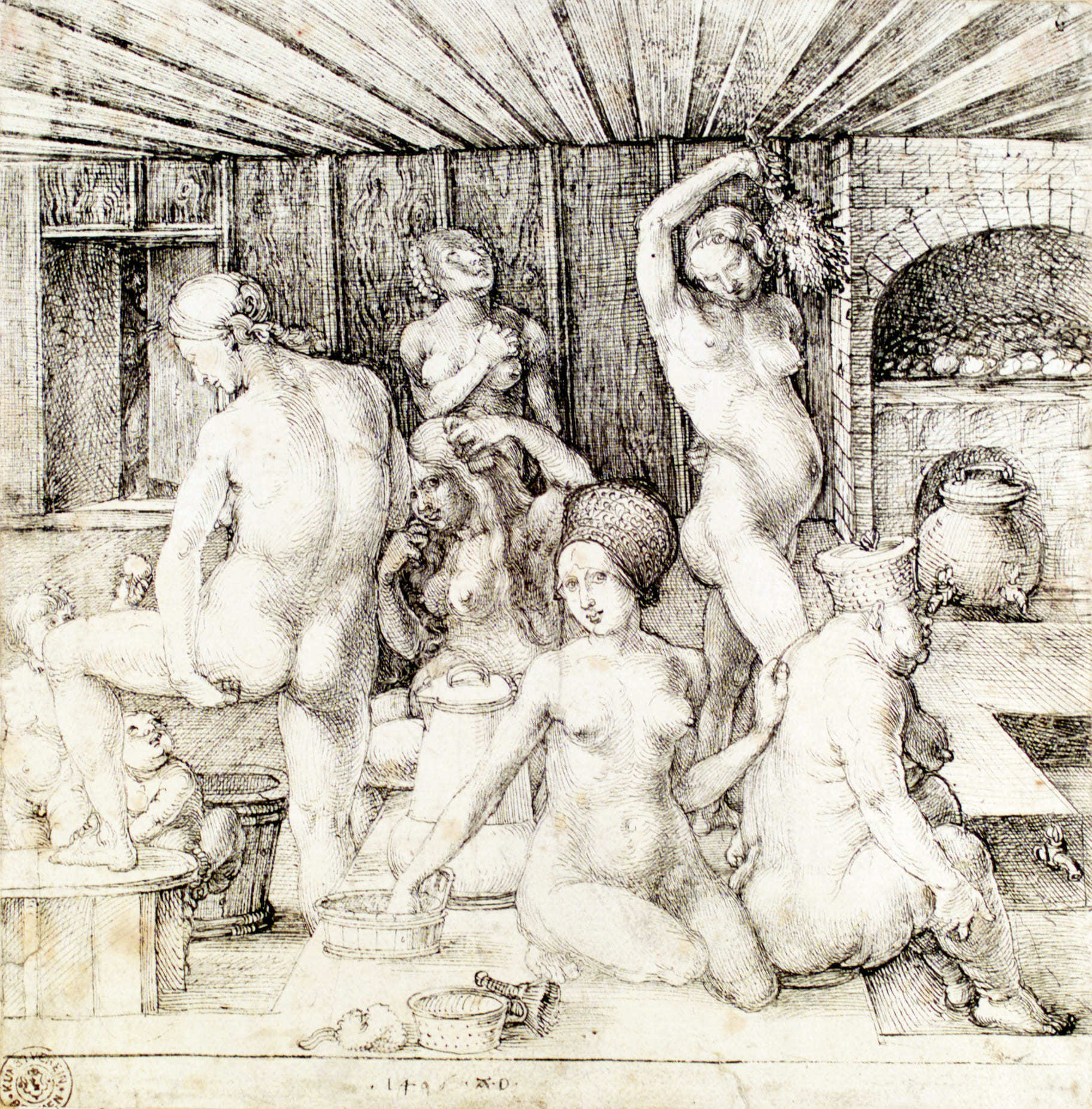

Albrecht Dürer, The women's bath, 1496

Albrecht Dürer, The women's bath, 1496© Kunsthalle, Bremen

It is also striking that the legal files within which these cases originated were much less hesitant to refer to female sodomy by name than their foreign counterparts. The sources state, just as they do for male offenders, that it was ‘buggerie’, ‘unnatural sin of zodomye’, ‘le villain pechié contre nature’ or ‘zodomie’. In the Southern Netherlands, the prevailing phallocentric view clearly did not stop the authorities from classifying sexual acts between women as sodomy.

A comparison with men was, however, never far off. As with male sodomites, a distinction was made between the active sodomite – the party who initiated the sin, and the passive sodomite.

Maertyne van Keyschote from Bruges, was, for example, charged as an initiator. She was flogged at dawn on Saturday, 10 June, 1514 by the executioner, then her hair was burned off and she was exiled from the city for a hundred years. Her accomplice, Jeanne vanden Steene, suffered the same fate. Both had committed ‘zekere groote specien vanden onnatuerlike zonde van zodomye’ (a certain large species of the unnatural sin of sodomy). Maertyne and Jeanne had tricked two ‘jonghe meyskins’ (young girls) Grietkin van Bomele and Grietkin van Assenede, into committing ‘eene specyen van zodomye’ (some species of sodomy) with them. Because of their youth, however, the two Grietkins were ‘merely’ flogged.

A lot at ‘stake’

Like male sodomites, women who committed this sin were severely punished. Fifteen of the 25 women were burned at the stake. Seven were flogged or exiled and only three were acquitted. With a mortality rate of sixty percent, the persecution of female sodomites came almost identical to the mortality rate of male sodomites. (The general mortality rate at the time was 62.06 percent).

Female sodomites were generally punished less severely elsewhere in Europe, and were often exiled rather than executed. Thus, the fact that these women were publicly executed in the Southern Netherlands and, moreover, that this often happened during sensational group executions, illustrates that the city authorities apparently did not consider it necessary to cover up the crime. Only seven women were individually prosecuted. The rest were part of a group process.

Jan van den Dale, De Stove, 1528

Jan van den Dale, De Stove, 1528© Wikipedia

For example, on Saturday 19 November 1482, six women were executed together at the Brugse Kruispoort. A seventh woman, Margriet, temporarily escaped this horrific punishment by convincing the aldermen that she was pregnant. For the duration of her pregnancy, she was spared. But on 18 August, 1483, not coincidentally nine months later, Margriet was also burned at the stake.

Most likely, these executions were carried out to serve as dire warnings. Women who “consciously chose” to commit sodomy, and thus transcend the natural order, were considered dangerous. We see this fear reflected in the broad definition of female sodomy that was used in the Southern Netherlands. In 1422, for example, Jehanne Seraes from Ghent was not only accused of sodomy, but also for wearing men’s clothes. The sixteenth-century Brussels aldermen executed Kathelyne Dominicle for bestiality with her dog and ordered the flogging of two women who had had a “carnal conversation” with some Turks. Sex with non-believers, non-Christians, was also deemed an unnatural act according to certain humanists.

Economically independent

Paradoxically, the fact that women had to adhere so strictly to this natural – meaning “heterosexual” – hierarchy was because they had an exceptionally high degree of visibility and freedom within the Southern Netherlands. Women were able to participate in public life much more than they did in other European regions. Girls were remarkably better educated and, up to a certain age, received the same education as boys. Thanks to the egalitarian law of inheritance, daughters inherited as much as sons, and a widow could become the head of the household rather than surrendering that role to her eldest son. As a result, women were better equipped than elsewhere to become economically independent.

Many women played an active role in the economic fabric of the Low Countries. As a ‘coopwyf’ (shop- or stall-holder) a woman was able to acquire a dominant position in the retail sector and was also able to work in atypical sectors such as printing, painting, blacksmithing and innkeeping. Foreign visitors noted with amazement the active roles played by women. As a result, the average age of marriage was higher than abroad and girls experienced a phase in their lives in which they could develop a more or less independent existence. Many women did not marry and thus, remained celibate. This did not, however, necessarily include vows of poverty and obedience. Beguine communities flourished in the Low Countries and, although beguines swore to lead a religious life, they had much greater freedom than nuns in closed monastic orders. Women in this region therefore enjoyed a great deal of freedom of movement on socio-economic, cultural and religious levels.

A danger to society

Unsurprisingly, that privileged position came with some responsibilities. In the fifteenth century, urban identity centred on the concept of the common good or ‘le bien commun’, which implied that every citizen was responsible for urban unity and the reputation of the community to which he or she belonged. In regions where women were more confined to the private sphere, sexual relations between women were less likely to come to light. The more visible women were in public space, the greater the chance that women who were attracted to women would be caught.

Giovanni Antonio da Brescia, Due Donne (1490-1525)

Giovanni Antonio da Brescia, Due Donne (1490-1525)© Wikipedia

Anyone who formed an integral part of the urban fabric was also partly responsible for upholding the honour and reputation of the community. Sodomy, in particular, posed a danger to the community at large. After all, in Biblical times, God had punished the entire population of Sodom and Gomorrah for the sins of individuals. It was because women’s contributions to society were more highly regarded than elsewhere that their missteps also had a greater impact on society.

In the period after 1550, an era when women’s access to certain economic sectors was systematically made more difficult and women were more often forced back into the domestic sphere, the number of female sodomites decreased drastically in the Southern Netherlands. Again, this suggests that the greater the visibility of women in the urban fabric, the greater the risk for women who engaged in sexual activity with women and the greater the need to make them atone for their sins and uphold the honour of the community.