Being and Existing. Trees and Forests in Awoiska van der Molen’s Photography

With her latest publication The Living Mountain, Dutch photographer Awoiska van der Molen continues two traditions. Her own modest search for places of human origin, and the broader historical contexts in which trees play a key role.

Trees are booming in anything but numbers. Scientists can’t seem to ascertain exactly how much forest is disappearing, and how much is added, but according to the most recent rapport of the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation, The State of the World’s Forest, 1,78 million square foot of forest has disappeared worldwide since 1990. A loss mostly ascribed to the tropics.

Awoiska van der Molen

Awoiska van der Molen© Studio Awoiska van der Molen

Especially in Europe the tide is slowly turning. To get an idea of this arboreal boom, type in the terms ‘protesting deforestation’ online. There is a collective realisation that we need forests. Trees are a weapon against climate change, improve our mental wellbeing, and are a crucial link in the worldwide ecosystem. Asides from this functional perspective, trees are associated with promise, growth, steadfastness, purity, and even wisdom. They are our superiors: trees have existed for almost four hundred million years.

These above verbs speak volumes: they are and they exist. This segues effortlessly into the visual works of Dutch artist Awoiska van der Molen (b. 1972).

Dust

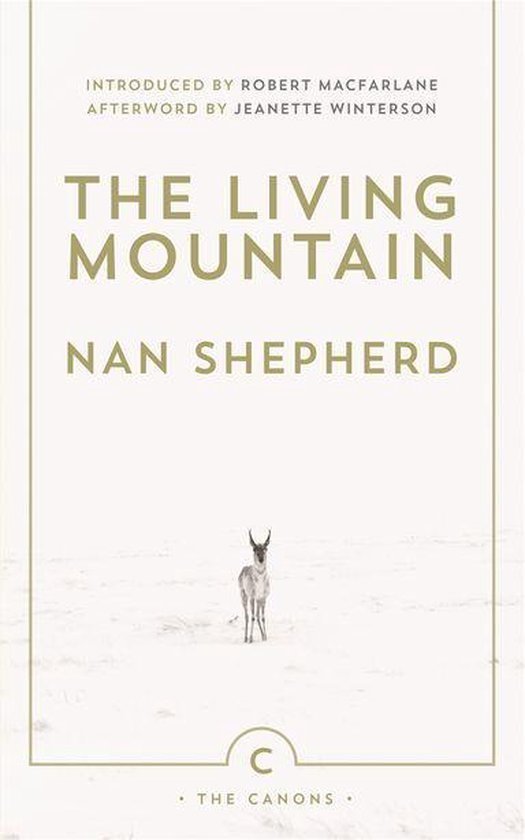

First a small detour – because after all, forests don’t offer those straight routes from point a to point b our impatience demands. Our detour is called Nan Shepherd: ‘So simply to look on anything, such as a mountain, with the love that penetrates to its essence, is to widen the domain of being in the vastness of non-being. Man has no other reason for his existence.’ This is a quote from that other, earlier publication The Living Mountain, by the Scottish writer Nan Shepherd.

Shepherd wrote her book in 1942, but because she struggled to find a publisher, the manuscript ended up on a shelf. It wasn’t published until 1977, thanks to Robert Macfarlane, another great nature writer. He was alerted by a friend that somewhere beautiful nature-prose was gathering dust. These days, it is seen as a seminal piece within the genre.

The Living Mountain provided both the vantage point and title of Van der Molen’s latest publication. She hiked, alone and for an extended period, deep into the mountains and forests of Tirol, at the invitation of composer Thomas Larcher. Larcher was born and raised in the area, and between 2019 – 2020 composer-in-residence at the Concert Hall in Amsterdam.He composed a score of the same name for Van der Molen’s publication, incorporated as the centre section. That is how five different people meet at the same start: The Living Mountain.

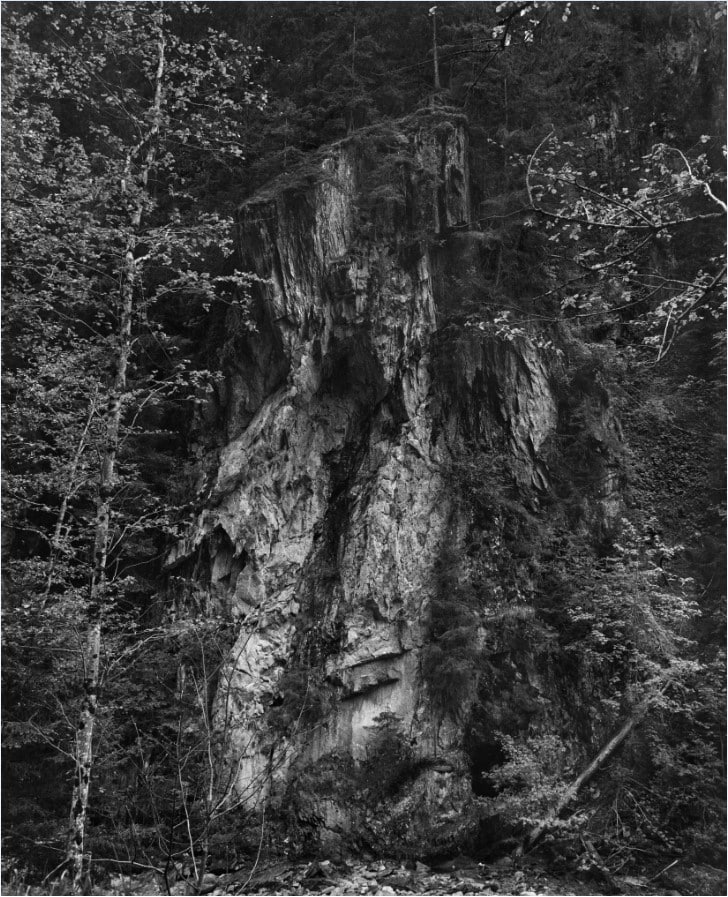

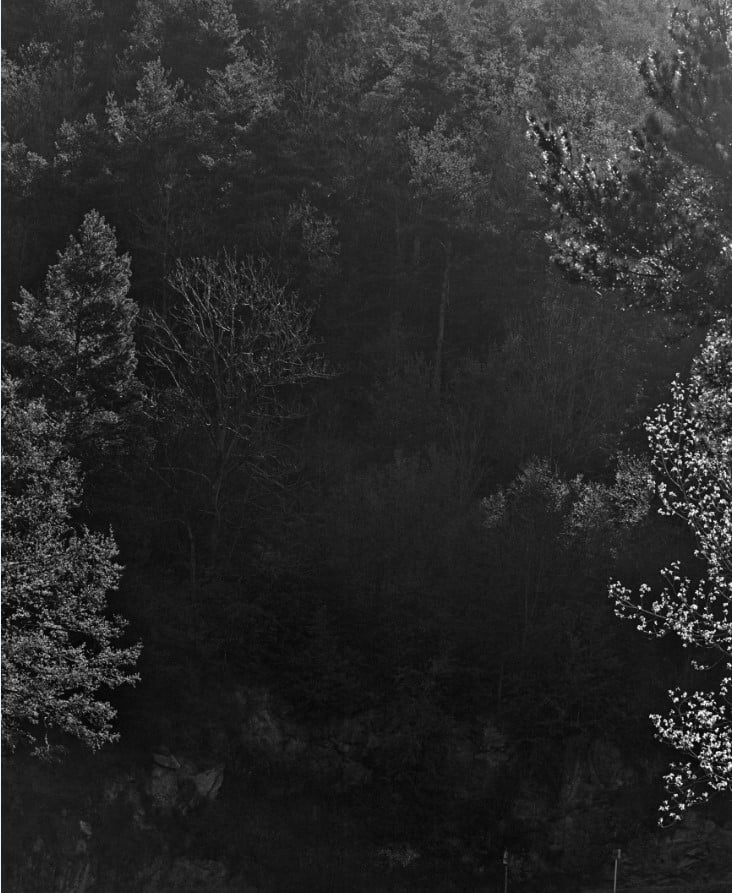

The Living Mountain - #570-18, 2020, silver gelatine print

The Living Mountain - #570-18, 2020, silver gelatine print© Awoiska van der Molen

Clearing

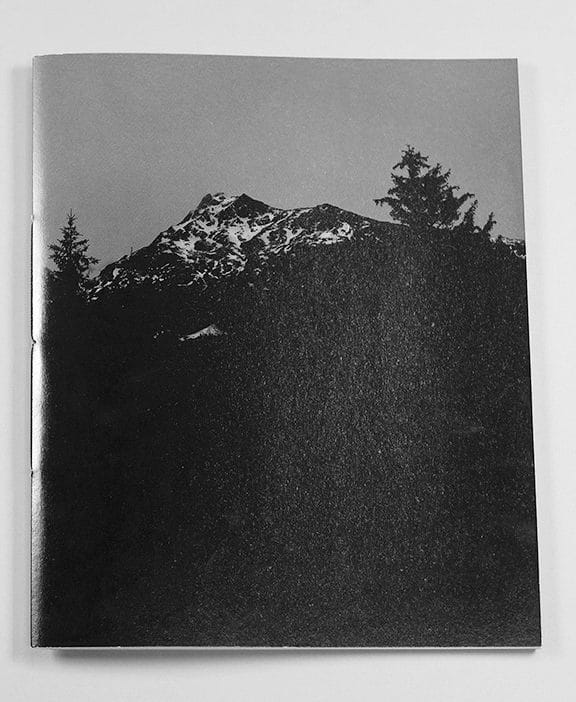

On light-coloured cardboard, Van der Molen presents seventeen black-and-white photographs: trees, mountain slopes, bare rocks. Alternating between the grey and white sides of the cardboard, she plays with the intensity of her images, pulling you into the deep dark of the shade, or letting your gaze float on the grey wave flowing through a sunlit valley. There is mist, there is mystery. There is detail in how she subtly focusses, and an abundance akin to what the hiker experiences in certain moments.

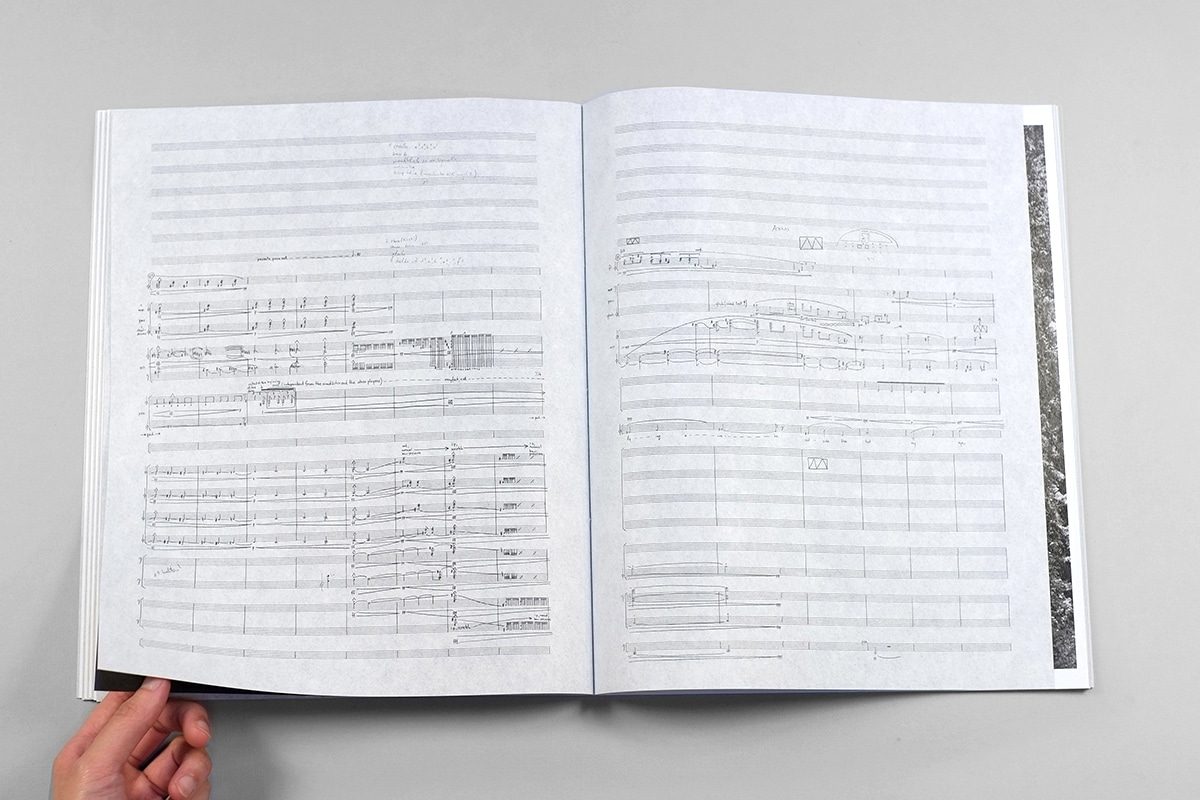

The mountain is the subject, but the trees are the characters in The Living Mountain. They even make an appearance in Larcher’s score, midway through the publication, creating an effect akin to a clearing in a forest, an open space where light can enter. The publication extends Van der Molen’s formalism onto wafer thin paper: one side black, the other side covered with the needle-sharp print of the score. Once printed, the music notation resembles a minimalist pine forest, the writing between the staff as directions for characters: ‘Let sticks bounce on the mallets (the arms moving up).’ You can see them sway, the branches. Yet to experience its sound, we have to wait a until the postponed world premiere in Amsterdam.

© Awoiska van der Molen / Fw:Books

Afterwards, Van der Molen’s photography leads you further into the forest. Past the treeline, to the cubic, futuristic, breathlessly unfocused landscape of snow and mountaintops. Bar a cable there is no sign of human presence – the steal line runs through the image like a reverberating piece of notation.

Then you descend again. The relief, almost palpable, to encounter life after all that barrenness: a tree.

The Living Mountain - #558-18, 2020, silver gelatine print

The Living Mountain - #558-18, 2020, silver gelatine print© Awoiska van der Molen

Tradition

Nature isn’t unknown territory for Van der Molen. In her earlier publications Blanco (2017) and Sequester (2014), both beautifully designed, like The Living Mountain, by Hans Gremmen, she returns to the ‘unspoiled origins of our past’. She is convinced that our body does not evolve at the same speed as the world in which we live. And that it suffers because of it. But also, that the body remembers when it approaches spaces once our natural habitat.

Blanco #380-14, 2015

Blanco #380-14, 2015© Awoiska van der Molen / Fw:Books

Van der Molen translates this desire for an almost ‘existential purity’ into a specific process: her monochrome, analogue images are a combination of artistic conviction and patient labour. She takes her time to immerse herself in the world she photographs, including when developing the silver gelatine prints. Her photographs bear no title: they are anonymous visualisations of a ‘universal knowledge’.

Sequester #274-5, 2011

Sequester #274-5, 2011© Awoiska van der Molen

From an art historical perspective, this subject and her approach to it touch upon tradition. The landscape, and especially the forest, have been subject to the photographic eye ever since its invention. Especially in the mid-nineteenth century – particularly in the United Kingdom – artists were fascinated by the landscape in which trees functioned as ‘living memories of the past that were identified with remarkable people, events or situations’. Trees were assigned a certain status, contrasted by a landscape mauled by human intervention in the background. This turned them into ‘comforting anchor points in a period of great change.’

Although Van der Molen’s photographic style does not align itself with the pictorialism propelled by Alfred Stieglitz (1864 – 1946) or Edward Steichen (1879 – 1973) – except for her conscious use of monochrome imagery – she does sign up to their vision of printing with patience, care and in limited edition, away from the commercial circuit. Because trees deserve better.

Silent witnesses

The motives of contemporary artists branch wide out like the crowns of trees: for some, their work becomes joined with an ecological wake-up call, others connect to it sometimes loaded issues of identity – trees also symbolize regions, nations and even political affiliations.

In Van der Molen’s work, writes British curator Martin Barnes in the book Into the woods: Trees in Photography, trees appear like silent witnesses to a more ‘psychological and spiritual quest’. No wonder that Van der Molen has opted for a Japanese bookbinding technique for her publication: like no other culture, the Japanese know how to elevate trees to symbols, amongst which male power and female sensitivity.

Van der Molen’s images keep holding your gaze. They go against the grain of the dominant contemporary trends in photography: they demand time and patient. They focus on the being and existence, not on movement as a symptom of a rapidly changing society.

The reward is significant: whatever people contain in emotion or projection is echoed in the monochrome landscapes. Or finds itself in conversation, for some. Whoever dares doubt the latter, should read Conversations with Trees by the American writer Stephanie Kaza. Or the nature-prose of Nan Shepard, of course. That would conclude the circle. Something trees appreciate deep inside.

Awoiska van der Molen, The Living Mountain, Fw:Books. Amsterdam, 2020, 48 pp.