Belgium Is Europe in Miniature

Belgium has an interim minority government to deal with the corona crisis. The emergency has exacerbated the division in the country. Will Belgium fall apart, or is it actually a laboratory for Europe?

© Michael Day / Flickr

At the edge of a bare field, on the top of a ridge near the village of Ploegsteert, stands a simple wooden cross. It commemorates the small peace in the Great War. On Christmas Eve 1914, British and German soldiers sang to each other from their trenches. Then, hesitantly, with their hands held high, afraid of a fatal shot, they climbed out of the trenches. Crossing no man’s land, the soldiers walked towards each other and greeted one another. They exchanged cigarettes and played a game of football. The superiors of these brave men quickly suppressed this ‘fraternisation with the enemy’. But their actions went down in history as an early attempt to form a European community.

Although Ploegsteert sounds Flemish, the village is actually in Wallonia. Has been since 1963. In exchange for the Voerstreek, or Fourons, in the northeast corner of Belgium, which went to Flanders, Wallonia was given this area in the far southwest. The village is now part of the municipality of Comines-Warneton, or Komen-Waasten.

I was here to investigate what it is that holds Belgium together still. A local dignitary calls Comines-Warneton the most Belgian of all municipalities. The mayor says that she feels one hundred per cent Belgian. If there is something that keeps Belgium together, this is perhaps the place to find it.

Comines-Warneton

Comines-Warneton© Wikimedia Commons

It might also be the place to discover whether European fraternisation still has a chance in times of identity politics. Because Belgium is Europe in miniature. A multilingual political construction in which the solidarity between the different communities is not particularly strong. Nationalist feelings play a strong role. There is a constant battle about whether money should flow from rich to poor or whether everyone should stand on their own two feet. There is a lack of the shared public sphere that comes from people reading the same newspapers, watching the same TV programmes and discussing the same issues and people. It is just like the EU.

A local dignitary calls Comines-Warneton the most Belgian of all municipalities

At Tabac XL yellowed paper covers the windows. Next door, the dingy Café des Douanes is closed and looks as if it is unlikely ever to reopen. They are the first buildings you see as you cross the bridge over the Lys and walk into Comines. Further down the street, too, abandonment and decay have struck. Amidst all this drabness, the open gate of a stately-looking house reveals a view of a lush garden. This is where lawyer Jean-Jacques Vandenbroucke has his office, the man who referred to Comines, in the French-language magazine Wilfried, as the most Belgian of all municipalities, and who was active in local politics there for thirty years.

Belgitude

‘Let me invite you for a meal. I imagine you’re hungry’, is the first thing he says to me. ‘I’ll show you my jazz club too’, he adds, confirming that particular cliché about Walloons, at least – they are very hospitable.

But I am already making a mistake by characterising him as Walloon. He is the grandson of a Flemish worker who was brought up in French, he tells me. Cross the bridge over the Lys and you are in French Comines. Tourcoing and Roubaix are not far. At the end of the nineteenth century, these towns were the heart of the European textile industry. In those days, many Flemings came to live in Comines, looking for a job on the other side of the bridge. ‘Now Flanders is one of the richest areas in Europe. But in those days Flanders was very poor’, Vandenbroucke explains.

Jean-Jacques Vandenbroucke, lawyer and jazz club owner

Jean-Jacques Vandenbroucke, lawyer and jazz club ownerBart De Wever, the leader of the Flemish nationalist party N-VA, rubbed salt into Walloon wounds at the end of last year, by saying that Flemings were supporting the ‘passive’ Walloon voters with billions of tax money. ‘If you go a bit further back in history than Mr. De Wever’, Vandenbroucke counters, ‘you will see that, from the creation of Belgium in 1830 to the 1960s, Wallonia was richer than Flanders. Because a lot of investments were made in Flanders, and Flanders has a maritime profile, while Wallonia has lost its industry, the situation was reversed. The Flemish economy is now stronger than the Walloon. Is that a reason to let the country be blown apart?’

The lawyer, whose office is full of old jazz posters and pleasant paintings, actually sees the cultural traffic between the communities as a Belgian asset. ‘That is that special something called Belgitude. I know Mr. De Wever doesn’t want to talk about it. But I think there are Belgians that have a real cultural link with that notion. Listen to the singer Arno, for example. He speaks French with an Ostend ring to it. I think his French numbers are fantastic. He says we’re a sort of laboratory in Europe because we have this double culture.’

It sounds rather blunt now that the great singer of ‘putain, c’est vachement bien, nous sommes quand-même tous des Européens’ is seriously ill, but isn’t seventy-year-old Arno the type of Belgian that is dying out? Those who follow the Flemish and Walloon media cannot get around the idea that they are two different worlds. They show different politicians and celebrities. The Flemish newspapers don’t waste a single word on the most important Walloon literary prize, and vice versa.

Belgian jazz guitarist Philip Catherine playing at jazz club Open Music

Belgian jazz guitarist Philip Catherine playing at jazz club Open Music© Facebook page Open Music

‘I’m an old Belgian, but I’m not daft, I realise that we have two different information systems and spheres of interest’, acknowledges Vandenbroucke. ‘But there are still bridges. Recently there was the presentation of the Magrittes, the Walloon film prizes. The best actress was Veerle Baetens, a Fleming.’ In the jazz club Open Music, which he founded a few years ago, he wants to have musicians from Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels play together. He set up a cooperative with seventy people. They put capital into an old dance club that had trees growing in it and converted it into a jazz club. Proudly he shows me the result. ‘It’s the only business in Belgium where you have to pay to work, says Vandenbroucke. What he means is that even the volunteers who stand behind the bar during the concerts, which are always sold-out, have to pay for their tickets – even him, the chairman of the cooperative. ‘This is a dream of a new democracy, a formidable demonstration that citizens can take matters into their own hands.’

Flemish actrice Veerle Baetens

Flemish actrice Veerle Baetens© Michiel Hendryckx

We eat in a restaurant – the country is not yet in lockdown – where a French chef and his Russian wife serve up haute cuisine with pancakes. ‘I don’t feel either French or Belgian. I just feel happy’, says our host as we leave. Vandenbroucke appreciates that. ‘It’s not because we vote, eat or make love differently that we can’t be part of the same community’, he says. ‘As long as you can see the beauty of a double culture and realise that solidarity is one of the greatest values we can defend, the Belgian state has added value.’

Laboratory

These are words that Alice Leeuwerck, the 29-year-old mayor of Comines-Warneton wholeheartedly endorses. ‘I feel one hundred per cent Belgian’, she says, in her office in the neo-gothic town hall. ‘My father comes from Poperinge, the hop region thirty kilometres from here’, she explains. ‘On my mother’s side, I have Walloon roots. I speak both languages and did part of my studies in Flanders. My identity card is in Dutch. I feel connected to both cultures, I read Flemish and Walloon newspapers. For concerts, I go to both sides. As mayor, I think it’s wonderful to represent Comines-Warneton as a Belgian town.’

Alice Leeuwerck, mayor of Comines-Warneton

Alice Leeuwerck, mayor of Comines-WarnetonTime and again the N-VA contends that Belgium consists of two democracies, two political communities formed by two different peoples. As long as independence is unachievable, the party is backing confederalism, a construction in which the federal states are largely autonomous and only shoulder a limited number of responsibilities, such as defence, together.

The mayor of Comines wants none of that. ‘I think that’s much too dualistic’, she says. ‘Here we have a lot more in common with the Flemish way of life and thinking than with those of people who live in distant parts of Wallonia. I couldn’t choose between Flanders and Wallonia. I think that Comines-Warneton is a laboratory for Belgium.’

It is a laboratory where the experiments are subject to inconvenient rules, though. After the transition from West Flanders to Hainaut in 1963, Comines was once again exchanged for the Flemish Voerstreek in 1988. In order to suppress the linguistic unrest there, a law was passed that the (Walloon) minority had to be represented in the college of aldermen and all decisions required unanimity. In the delicate game of checks and balances the same regime was imposed on the Walloon Comines-Warneton.

It is a typical Belgian compromise. Time and again, makeshift solutions have been devised to curb the divisions between language groups and political movements. Meanwhile, the Belgian state system has become an inextricable tangle. The country is composed of three regions – Flanders, Wallonia and Brussels – and three communities – the Flemish, the French and the German. They each have a government and a parliament, except for Flanders, which has amalgamated the region and the community. The result is that only seasoned specialists understand who does what and that a lot of work is done twice or not at all. By four climate ministers, for example, who cannot even manage to present a proper national climate plan to the EU.

Nearly all Belgians find this administrative lasagne unpalatable. But with every attempt to dish up something new it just goes from bad to worse. Dave Sinardet, professor of political science at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), has an apposite name for it: the perpetuum mobile of state reform. ‘Again and again’, he explains in an Antwerp café, ‘the diagnosis is that the system is too complex, not transparent enough, too inefficient and too expensive. The solution is state reform. For years all the political energy and resources have gone into that. And after a lot of blood, sweat and tears it has become even more complex. This sort of state reform is a compromise between a great many parties. It will never be the perfect model you would come up with if you looked at it purely from the point of view of the essence.’

In Comines, this complexity can be seen in miniature. Even though Flemish parties no longer participate in the elections, the 1988 regulations still give the opposition the right to participate in the college of mayor and aldermen. Leeuwerck has formed a narrow majority with two other parties in the municipal council. But in her six-member college there are three politicians from the opposition.

‘Every Monday evening, I have to negotiate. It’s the opposition against the majority, three against three’, says the youngest mayor in Wallonia. ‘As for the negotiations for a federal government – I do that every week. We have to find a solution. We work for our citizens.’ If the college does not approve an item because there’s no unanimity, the municipal council debates it. Leeuwerck thinks it is healthy that the population elects the aldermen directly and that the council has a lot to say. ‘Comines is a laboratory for democracy, and it works well.’

Comines is a laboratory for democracy, and it works well

Politics in Comines are certainly not cosy. The Christian-democrats on the local Action list won more votes in the elections in October 2018 than Leeuwerck’s party Ensemble. Nonetheless, she was able to form a coalition with a majority. Now opposition leader Marie-Eve Desbuquoit, who dreamed of becoming mayor, is getting her own back. During a New Year’s speech, she said that the present coalition ‘goes against every nature’, is taking revenge, isolating her party and refusing any cooperation.

On a Monday evening in March, I go to the meeting of the municipal council to see whether it is still possible to work in Leeuwerck’s laboratory. The sober neogothic room is packed. An elderly man who has to stand all evening has come for his son, who sits on the council for the opposition party Action. He says spontaneously that he is charmed by the mayor. ‘She is energetic and intelligent.’

The council performs the spectacle of local politics with verve this evening. During the round of questions that opens the meeting, one member asks a question about the church cock, which wobbled dangerously during the storms in recent weeks. Another wants to know what the municipality is doing to curb the corona virus.

While Action’s aldermen sit staring ahead, sullen and silent, Leeuwerck leads the meeting cheerfully and dynamically. The pièce de résistance of the evening is a system of incentives for those who want to open a retail outlet, catering business or office in the municipality. It is built up layer by layer, like a lasagne, explains Leeuwerck. An initial basic sum of five hundred euros, with additional premiums on top of that for those who establish their business in the heart of one of the old municipal centres, repurpose a vacant old building or make an effort in terms of sustainability. For all the parties that support the plan, including the opposition party Action, this is a tasty lasagne, she jokes, not to be compared with the Belgian administration.

The Belgian town of Comines is separated from the French town of Comines by the River Lys

The Belgian town of Comines is separated from the French town of Comines by the River Lys© Google Maps

Time will tell whether strolling through the shopping streets later on will be pleasant again. But what is certain is that the young mayor, a political talent who is tipped in the media as a future minister, is cheerfully working on all kinds of plans. One example is the new port on the Lys, the river that runs along the town and forms the border with France. Belgium and its southern neighbour are cooperating to make the waterways from south to north suitable for large ships and to dig a canal linking the Seine and the Lys. ‘Wallonia is investing massively in Comines-Warneton’, says Leeuwerck. ‘We are the only Walloon town on the axis between Paris and the North Sea ports. We are considered to be an economically important region.’

An aberration

Sixty kilometres from Comines, Jean Bourgeois, professor of archaeology in Ghent and a member of the historical circle of Comines-Warneton, puts the developments in the region in a broader perspective. In his study, which is full of photos of the Russian Altai Mountains, where he studies the Iron Age burial mounds, he tells how the region has been tossed about on the waves of political and economic history. Once upon a time a Picard dialect was spoken here. It first became Flemish at the end of the ninth century, when the area was part of the county of Flanders. A millennium later the flourishing northern French textile industry brought about the strongest wave of ‘Flemification’. However, when the industry declined, the Flemish workers left again, and the French language gained the upper hand.

professor Jean Bourgeois

professor Jean BourgeoisIn his own life too, Bourgeois commuted to and fro between the two languages. He was born in Congo, where he spoke French. In the troubled days after independence, in July 1960, he was evacuated to Belgium. There the young Jean went to school in Dutch-speaking Ghent. When he was about ten, his father took over his parents’ restaurant in Warneton. And there he spoke French. At the age of eighteen, he went to study in Ghent, where he stayed for a while. But the region where he lived during his formative years at secondary school never left him. ‘I still feel I’m a Warnetonian. When I drive to the meetings and see that landscape, in the yellowish light of the low winter sun, I feel like I’m coming home.’ Perhaps it was necessary to pacify the language battle. Nevertheless, Bourgeois thinks it was ‘an aberration’ for Belgium to enshrine the linguistic boundary, demarcating where Dutch and French are the official languages, in the constitution. ‘As if you were to define the boundary of an animal species’s habitat. We are the only people in the world who have done this.’

In the eighties, emotions ran high in Comines due to the language question. Supporters of the Flemish movement set up a Dutch-language school in the face of protest from the Walloons. ‘At one point, people who followed it in the newspapers had the impression that it was a sort of Northern Ireland here’, says Bourgeois. He and his historical circle organised a congress during that time. Colleagues of his from Ghent came and stayed in his parents’ hotel-restaurant. ‘They didn’t dare to speak Dutch and asked in broken French whether there was a room free’, he says, laughing. The linguistic battle has died down, Comines-Warneton has been Gallicised. But that does not mean the language problem has been eliminated.

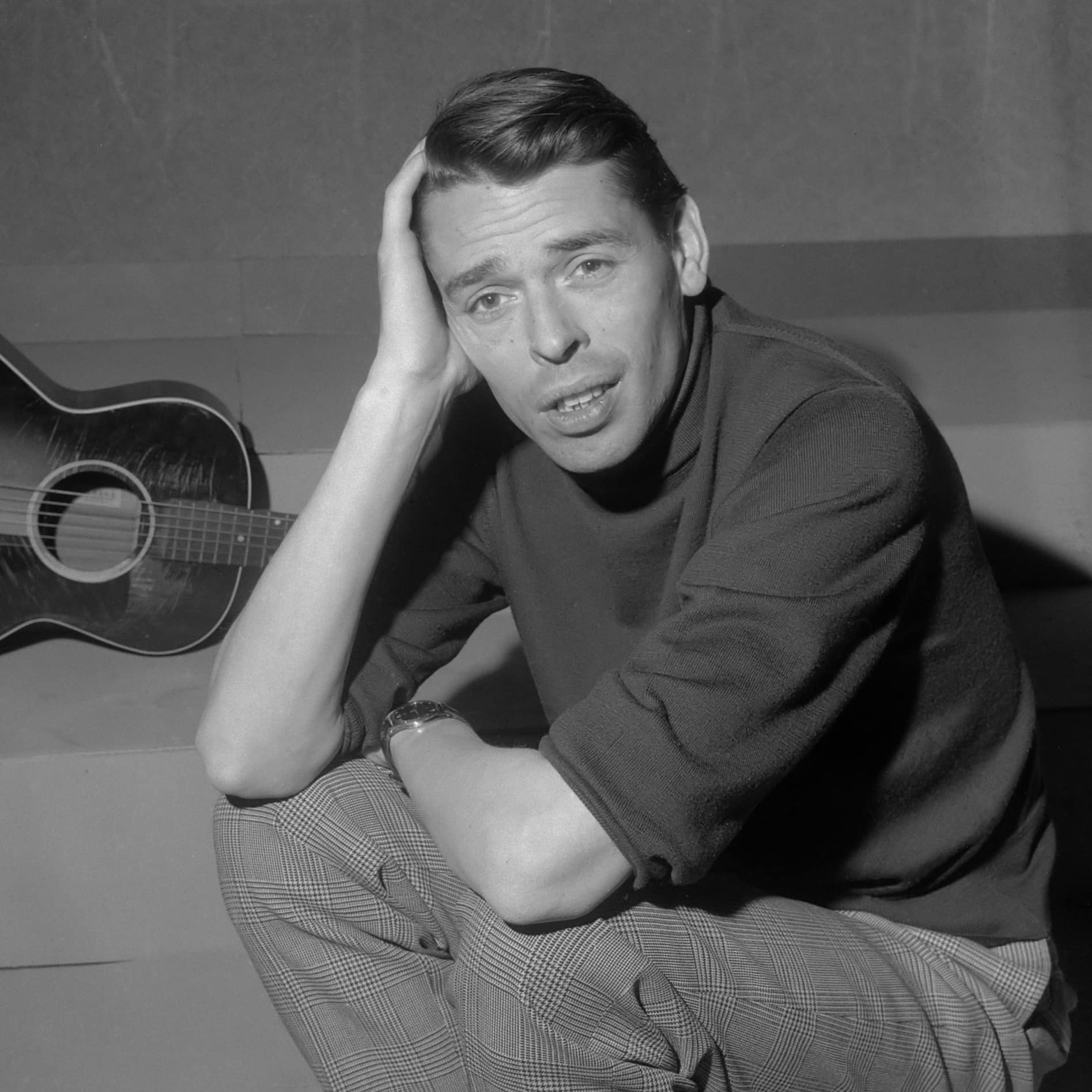

Jacques Brel

Jacques Brel© Wikimedia Commons

Because, as the philosopher John Stuart Mill believed, it is so essential for the formation of a political community. ‘Among a people without fellow-feeling, especially if they read and speak different languages, the united public opinion, necessary to the working of representative government, cannot exist.’ In the Netherlands, perhaps because the right to speak one’s own language has never been disputed, we are quick to think that the rise of English has put an end to this question. But Bourgeois does not believe in English as a lingua franca, ‘My culture is a French-language culture. When I came to study in Ghent, everyone was under the spell of the singer Boudewijn de Groot and poet Jotie T’Hooft, who had died very young. I had never heard of them. I was busy with Maxime Le Forestier, Brel and Brassens, French-speaking singers.’

Ending up on an island

‘One of the big mistakes was that we did not put enough effort into the other community’s language’, agrees political scientist Sinardet. ‘Certainly, on the French-speaking side it’s a disaster. At Walloon schools you only get a second language in the first year of secondary school. Moreover, you then have to choose between Dutch and English initially, a criminal choice. In Flanders, too, the knowledge of languages is deteriorating noticeably. You might say, of course, that Europeans don’t all have to speak each other’s language either to make the EU work, but if you want to maintain a federal democracy with two large language communities, it helps if you make sure you know each other’s language.’ As a university teacher, Bourgeois has daily experience of the fact that the lack of language knowledge is creating a cultural gap. ‘If I tell my students something about the other side, from a geographical, historical or political point of view, they know nothing about it’, he says. ‘They can’t name a politician, unless one has done something wrong. And conversely, my Walloon colleagues don’t know the Flemish politicians anymore. Yes, Bart De Wever of course. The man has already got on the Walloons’ nerves enough.’

Bart De Wever, leader of the Flemish nationalist party N-VA

Bart De Wever, leader of the Flemish nationalist party N-VA© Miel Pieters / Wikipedia

At the end of February, the leader of the Flemish nationalists trod on people’s (already sore) toes yet again. ‘Belgium has been dead for ten years. This country is finished. Absolutely finished’, he said. That was De Wever’s reaction to the decision of the Walloon socialist leader, Paul Magnette, to put an end to the negotiations with the N-VA. The elections of 26 May 2019 resulted in a total impasse. In Flanders the N-VA is the biggest party, in Wallonia the Parti Socialiste. Without these two, who are constantly railing at each other, it is extremely difficult to find a majority. In Flanders, the other parties are wary of entering a government without the N-VA. Without it the Flemish parties would represent a minority of the Dutch-speaking population. They are afraid that voters would punish them for that at the next elections and that the far-right Vlaams Belang would benefit from it.

Even the crisis in which the country finds itself now, due to the corona epidemic, turned out not to be enough for them to bury the hatchet for a while. Bart De Wever tried to profile himself as a statesman by offering to become prime minister of an emergency government with the PS. On the Walloon side it was seen as an attempt to misuse the corona crisis to seize power and further dismantle Belgium. After the breakdown of the negotiations, politicians blamed their colleagues on the other side of the border in unusually vehement terms. The president of the Flemish socialists tweeted that he was ‘disgusted’ that some politicians only fight for their own party while others have to fight for their lives. For his part, the leader of the Walloon liberals thought it was surreal to want to further regionalize the country at a time when national unity is more necessary than ever.

Sophie Wilmès, Belgium's first prime minister

Sophie Wilmès, Belgium's first prime minister© Wikipedia

To alleviate the present situation, a new interim government has been put together. The incumbent caretaker prime minister, Sophie Wilmès, can continue with a few powers of attorney. The parties in her government represent 38 of the 150 seats in parliament. A reason for leaders of the N-VA to denounce the democratic legitimacy of this cabinet. Meanwhile, they are angry that Europe wants to give two thirds of the corona budget to Wallonia, whereas Flanders has more victims.

No one can see a structural way out, not even Bourgeois. ‘I’m not a politician, but my feeling is that Flanders and Wallonia have been pushed so far apart that, from a historical perspective, you can’t keep them together much longer.’ As the son of a Walloon father and a Flemish mother, he feels completely Belgian. But he fears that meanwhile the communities have been driven too far apart. ‘What I think is a real pity is that there’s a development towards isolating ourselves from groups that are different. Soon you’ll only have your own street, your own side of the street, your neighbours, and finally, you’ll be the only one left. What bothers me most about this development is that we reject those who are a bit less well-off and we end up on an island.’

Is there no chance at all then of turning the tide? For years Dave Sinardet and some of his fellow academics have been advocating a so-called federal constituency. As a Fleming you can only vote for a Flemish politician now. ‘In the elections on 26 May I was unable to express an opinion about the party that supplied the prime minister’, says Sinardet. ‘If I thought that prime minister Charles Michel had done a really good job, I could not express that by voting for his party. And if I thought that he had made a mess of it, I couldn’t show that either. Political parties can govern the whole country, but only have to be accountable to half of it.’

One of the essential problems is the mutual diabolization

From a democratic point of view that is unhealthy and results in politicians only trying to appeal to the voters in their own linguistic community. In order to change that, Sinardet and his friends want voters from the whole country to be able to vote for some of the seats in parliament. ‘That might remedy one of the essential problems, the mutual diabolization, says Sinardet. ‘I am also a proponent of a European constituency. I think we have the same democratic deficit in the EU.’

Belgium’s weakness is also a strength, thinks the political scientist. The old idea is that a well-functioning democracy needs a public sphere where debates on social issues take place before the eyes and ears of the whole population. The problem with that idea is that it was formed at a time when the nation state was dominant and had all the important powers to decide on the fate of its inhabitants. But that time is gone. A lot of power has shifted to transnational decision-making fora like the European Union and the World Trade Organisation. The world is economically globalised. That means that you need to organise the political counter-power at a higher level. And with that the concept of the public sphere must also be revised.

‘We must look for new forms of democratic legitimacy for constructions such as the EU’, says Sinardet. ‘In that respect Belgium may not be a construction fault, but a laboratory for how we can rethink the public sphere in a post-national world.’

© Wikipedia

Belgium a testing ground for Europe? It is an appealing thought. But the question of what exciting experiments are taking place there does not yet give a very hopeful answer. ‘Too few, unfortunately’, acknowledges Sinardet. ‘A federal constituency might be an interesting experiment. If it were a success, it might inspire Europe.’ A nice idea, but we do not seem to be getting any closer to it either in Belgium or in Europe. ‘When I launched the proposal about seventeen years ago, people regarded me as an academic from an ivory tower’, counters Sinardet. ‘In the meantime, the proposal has gained support from various parties, intellectuals and journalists. It is part of the public debate, although there is not yet a majority for it.’

Bourgeois is also a staunch supporter. But he does not think it is realistic. ‘You can dream about it, but it will never happen.’ The economic and mental separation between Flanders and Wallonia is a fact, he thinks. ‘At a certain moment Flemings said, we’re rich and they’re poor. And then you get the Lombardy and Catalonia effect – we’ve had enough of that lot. Then Bart De Wever takes a busload of money to the border, to show they spend all this money on Wallonia. And then you get politicians complaining that all the European money for climate policy is going to Hainaut and that Flanders isn’t getting anything. We’ll never get anywhere like that. And it isn’t going to change.’

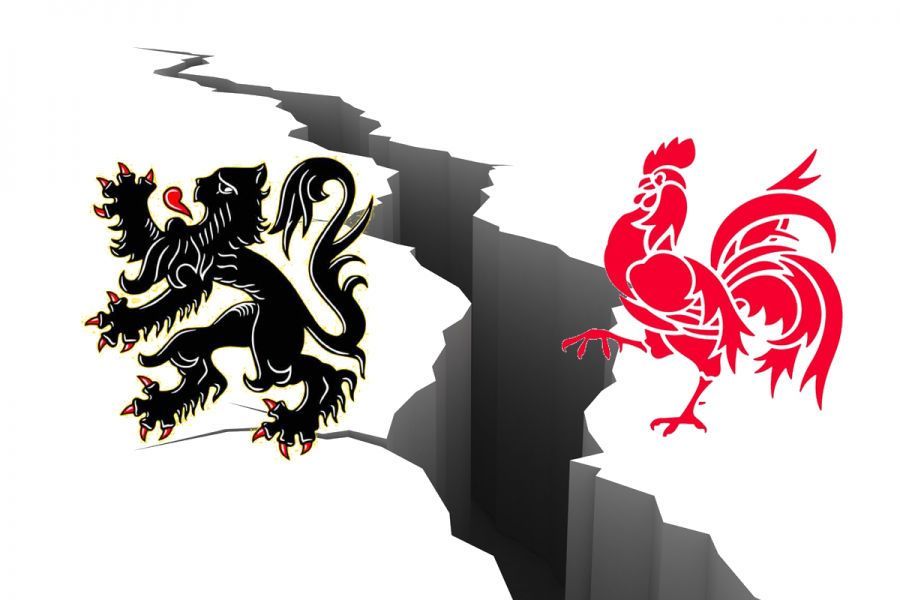

Flemings and Walloons grow apart

Flemings and Walloons grow apart© VRT

Yet Bourgeois does not see Belgium breaking up anytime soon. Neither the Walloons nor the Flemings will want to give up the city of Brussels, which is so important economically and politically. And what do you do with the common institutions? The Museum of Art & History and the Museum of Fine Arts? What is Flemish and what is Walloon art, what is Flemish and what is Walloon property?

Wallonia and Flanders have drifted apart, but the country cannot be split either. ‘It’s a catch 22’, says Bourgeois. ‘It would help a lot, if people on both sides would demonize the other less. But that kind of rubbish gets you votes. To be honest, I don’t really know where it’s going to end. In a world where intolerance is growing, things might well become serious at some point.’ The only thing we can hope for in Belgium and in Europe, at the moment, is that a new generation of politicians like Alice Leeuwerck will climb out of the trenches, learn to understand the other side and briskly deal with the problems.

The original, Dutch-language version of this article previously appeared in De Groene Amsterdammer.