Ben Sledsens Shapes Art History Into Personal Utopias

Ben Sledsens (b.1991) paints colourful ideal worlds, building an ever-expanding dream universe that combines personal mythology with a close reading of art history. People are queuing up to be a part of it.

It is easy to see why demand is so high for the work of this young Antwerp-based artist. He produces rich, colourful scenes that begin stories the viewer is invited to complete. They are open to interpretation in a way that draws you in, rather than sending you away scratching your head. And his visual language is accessible, reaching back into art history for images that are at once familiar and intriguing. He is a painter who deals in mysteries rather than mystification.

Ben Sledsens

Ben Sledsens© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

The media likes his work too, but it also likes the tale of a young artist who has become an overnight sensation. Press coverage of his third solo exhibition at Antwerp’s Tim Van Laere Gallery last September noted the crowds waiting to get in — due to covid restrictions, but still a handy image — and the fact that all 22 canvases inside had already sold to institutions and private collectors around the world. There is a waiting list for the work yet to come.

But like many overnight sensations, Sledsens’ rise is less dramatic than it seems. It looks fast because he was picked up early, just after his graduation from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp in 2015. A first solo show at the Tim Van Laere Gallery followed in 2016, a second in 2018, and the third in 2020.

Ben Sledsens, Girl in Peach Dress, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 150 x 5,6 cm

Ben Sledsens, Girl in Peach Dress, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 150 x 5,6 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

The two years between each show represent slow, hard graft. Sledsens is not a fast painter, taking as much as a month to produce each of the large canvases. Scarcity is built into his method, which naturally makes the demand all the more apparent. But the time he spends on each canvas is clear to see in the rich textures and carefully composed colours, produced by combining acrylics, oils and occasionally spray paint.

At the Academy, Sledsens was a talented painter of conventional still lives and landscapes, until the transforming experience of visiting a Georg Baselitz exhibition in Munich. Seeing these enormous canvases brought home the importance of scale, while the freedom Baselitz felt from convention, with his perversely upside-down portraits, taught Sledsens that he could also go his own way.

In particular, seeing Baselitz gave Sledsens permission to go back to the strip cartoons he loved as a child and bring some of their themes and techniques into his work. This meant that narrative was allowed. Strong characters were allowed. And there was no problem with pictorial simplicity, which can look naive in academic art, but is accepted as a creative choice in cartoons.

Ben Sledsens, Rowing on the River, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 290 cm

Ben Sledsens, Rowing on the River, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 290 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Sledsens also found a touchstone in the French post-impressionist painter Henri Rousseau, whose jungle scenes embrace flatness yet still conjure up rich textures of vegetation. Some of his paintings are direct homages, such as Tiger in the Jungle (Hommage Henri Rousseau) (2016) and Jaguar in the Jungle (2018). But Rousseau’s way with foliage also creeps into Sledsens’ early interiors, filling out flower shops or domestic scenes. There is a strong flavour of Matisse here as well.

In interviews, Sledsens often talks about his fascination with art history and its continuing inspiration. In addition to Rousseau and Matisse, he often cites Pieter Bruegel the Elder, for his treatment of landscape. But his choice when invited to pick favourites

from the collection of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp is also instructive.

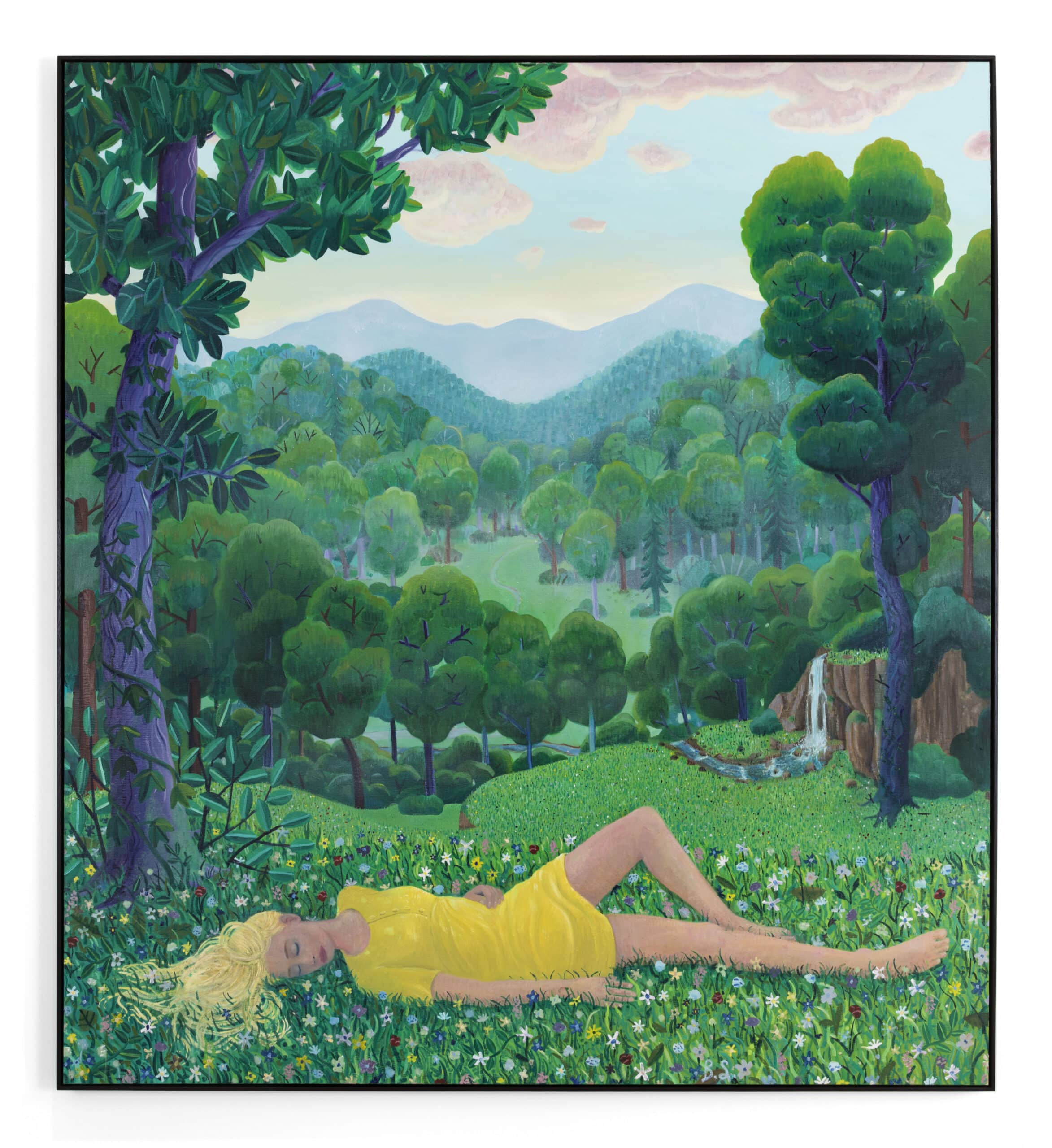

Ben Sledsens, Girl Lying in the Grass, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 230 x 210 cm

Ben Sledsens, Girl Lying in the Grass, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 230 x 210 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

First of all, he singled out Jean Brusselmans, an artist loosely connected with Flemish expressionism, who created flat, stylised landscapes that were still perfectly recognisable as Flanders. There is something of Brusselmans’ angular clouds in some of Sledsens’ paintings, and a nagging sense of familiarity in the lay of the land. Then he chose James Ensor, not for one of his celebrated carnival masks or skeletons, but for The Cuirassiers at Waterloo (1891), in which a vortex of mounted French soldiers presses down on a square of British infantry.

Ensor is cited for his free touch and his use of colour, but there is also a connection here in the action. Sledsens is fascinated by medieval themes, and from his second solo exhibition onwards knights start to appear in his paintings. Treatments range from close combat in The Battle (2018), apparently inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry but with echoes from across the history of chivalric painting, to the figures lost in a landscape in Two Knights and a Lady (2018).

Ben Sledsens, Two Knights and a Lady, 2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, 230 x 210 cm

Ben Sledsens, Two Knights and a Lady, 2018, oil and acrylic on canvas, 230 x 210 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

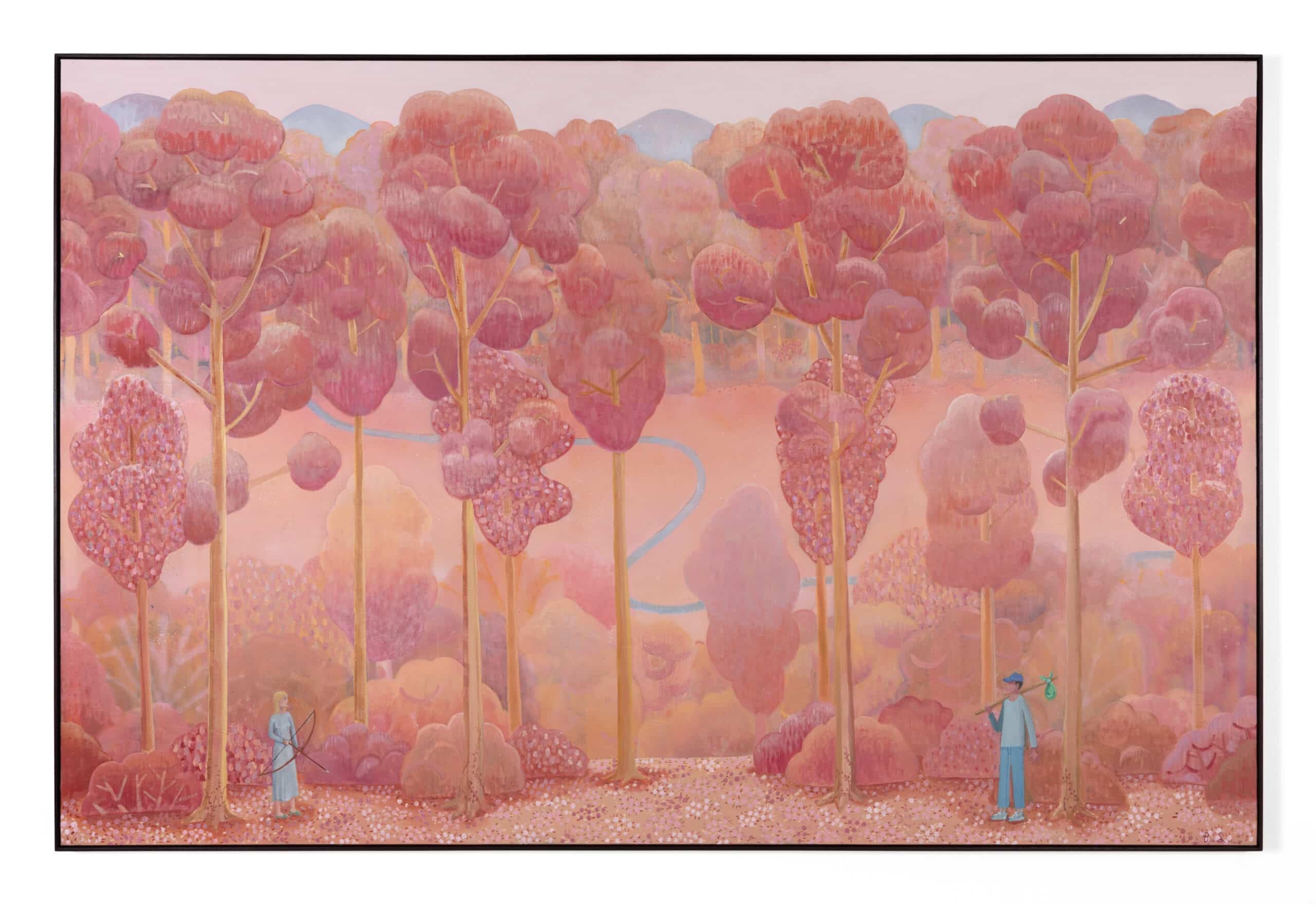

These paintings are also part of a trend in Sledsens’ work, away from scenes taken from contemporary life, towards a more allegorical or folkloric approach. The stylised vegetation no longer slips into the background of a restaurant or kitchen, but makes up the whole world, while the distant figures of knights, hunters, or straying dogs draw us in. Following the story will take us there, into the forest or into the night.

Ben Sledsens, The Huntswoman and the Wanderer, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 290 cm

Ben Sledsens, The Huntswoman and the Wanderer, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 190 x 290 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

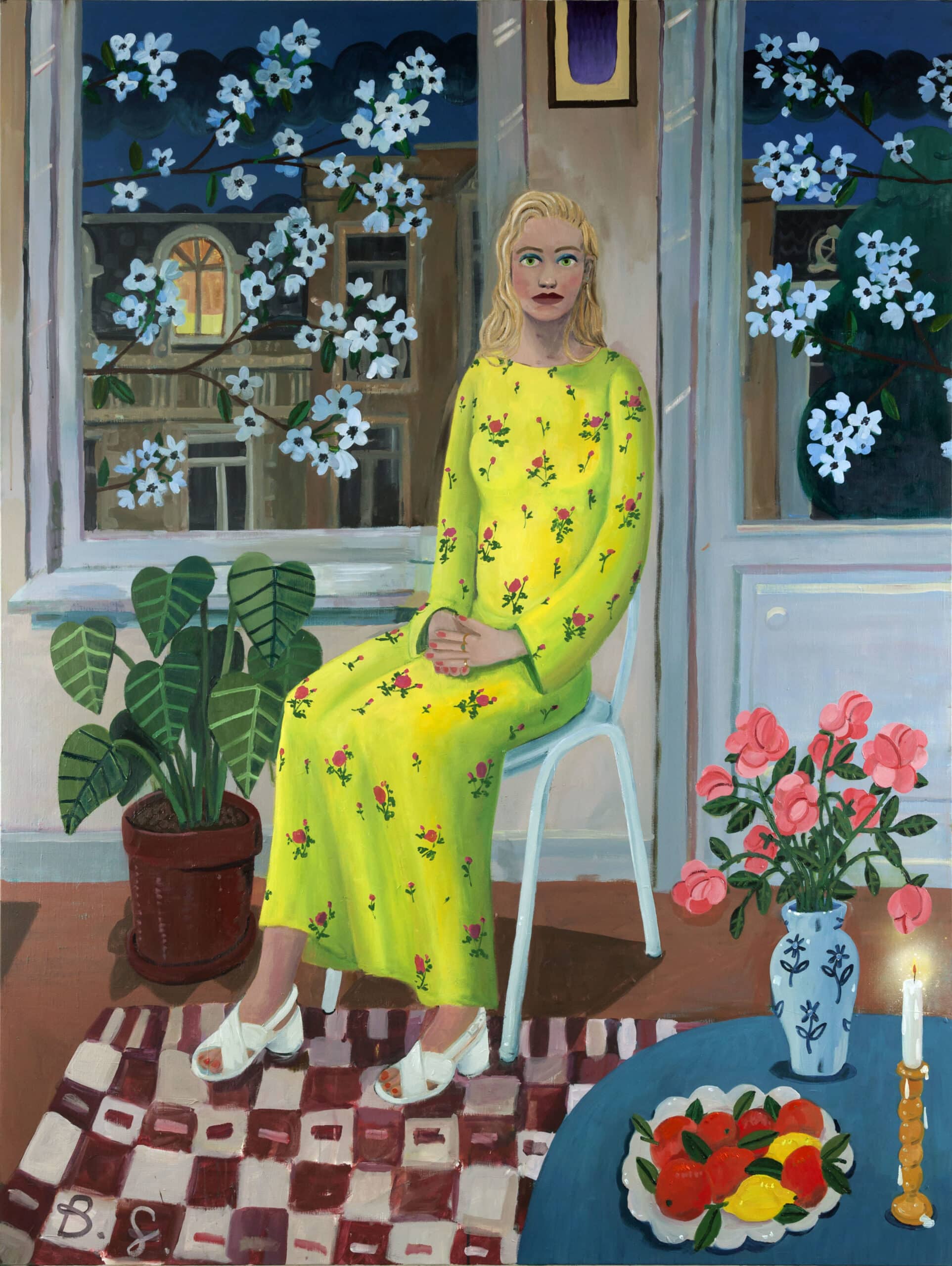

Two recurring archetypes in Sledsens’ paintings have a personal significance: The Wanderer, a bundle on a stick slung over his shoulder, represents the artist himself, while The Huntswoman represents his girlfriend, the fashion designer Charlotte De Geyter. She is also the model in Girl in the Yellow Flower Dress (2018), and her creations appear throughout Sledsens’ full-length portraits of women, although apart from her, each model is apparently imaginary.

Ben Sledsens, Girl in the Yellow Flower Dress, 2018, oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 200 x 150 cm

Ben Sledsens, Girl in the Yellow Flower Dress, 2018, oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 200 x 150 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

There are still hints of Matisse and Rousseau in the plants that appear in these portraits, of Bruegel and other Flemish Primitives in the landscapes seen behind them. But the strongest echo is of David Hockney, in the posture, and the way each sitter dominates the frame, looking directly out of the canvas.

Other archetypes in Sledsens’ work include woodcutters, bird-catchers and rat-catchers, all in modern dress but with floral borders or backgrounds that strongly recall medieval religious paintings. It seems entirely logical that Sledsens has been commissioned to produce a floral stained-glass window for the restored Saint Gertrude’s Chapel in the grounds of Gaasbeek Castle, in Flemish Brabant.

Ben Sledsens, Shooting Apples, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 300 cm

Ben Sledsens, Shooting Apples, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 300 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Very occasionally the characters in Sledsens’ paintings are recognisable, such as the version of William Tell in Shooting Apples (2019-20), or Devil in a Suit (2020), in which the Adversary stands in a flat Flemish field, engaged in a sword fight with someone just out of the frame. In both cases the viewer is challenged to complete the narrative, to puzzle out what is happening and why. And while Devil in a Suit is immediately funny, it also creates a frisson, perhaps stirring a folk memory of warnings that we all might meet the Devil while walking in the fields.

Ben Sledsens, The Devil in a Suit, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180 cm

Ben Sledsens, The Devil in a Suit, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

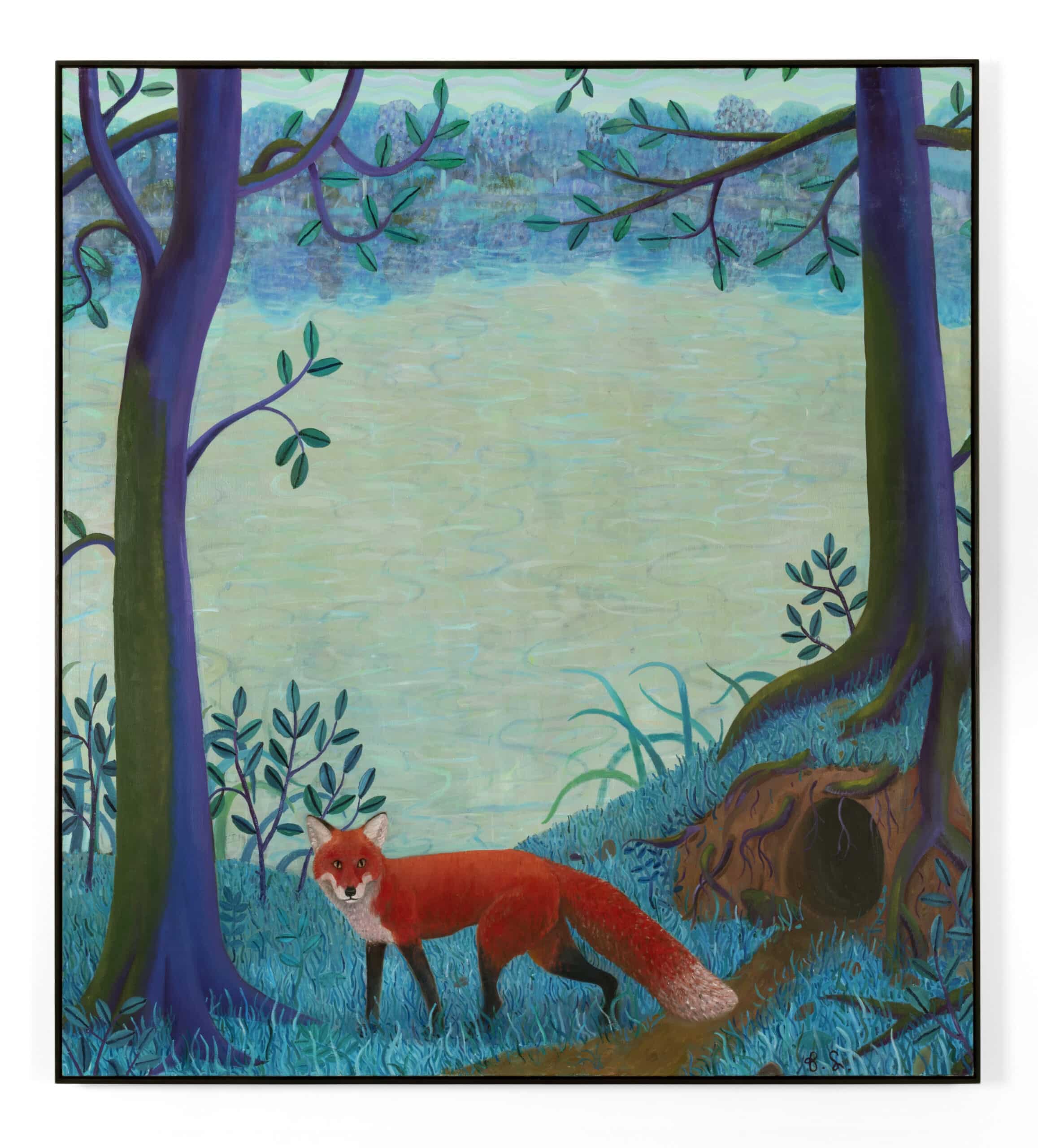

Folk tales are also present in a recent series of animal paintings. The traditional characters of these hares and tortoises, foxes and magpies are implied rather than their stories retold, and Sledsens says he is not interested in delivering the moral lessons that go with the fables. Instead, each image is an attempt to solve recurrent problems in landscape painting. How to depict nature without getting trapped in endless greens? And how to deal with empty space?

Ben Sledsens, The Red Fox, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180 cm

Ben Sledsens, The Red Fox, 2019-2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 200 x 180 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Each of these animal paintings shares a form: trees to either side, the fabled animal at the bottom of the frame, and in the middle a void, a long view to a lake. Each canvas takes on an intense colour, connected with a season, the weather, or a time of day. In The Red Fox (2019-20) it is a nocturnal blue, in Magpie with Pearl Earing

(2019-20) it is a sunset yellow. The result is a narrative tension between the literal story of the animal in the foreground and the atmosphere created by the colour and texture of the void. Do we follow the animal in its journey across the frame, or fall into the centre?

Ben Sledsens, Morning Encounter, 2019-2020, 3 panels, oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 250 x 555 cm

Ben Sledsens, Morning Encounter, 2019-2020, 3 panels, oil, acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 250 x 555 cm© Courtesy Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

These paintings demonstrate a more recent influence, Claude Monet, which is also apparent in Morning Encounter (2019-20). This is another painting with a void, spread across three panels, more than 5 metres wide. A walker in jeans, t-shirt and sneakers — perhaps The Wanderer once again — looks across a lake to where a naked woman is bathing.

The distinction is that Monet was painting from life, whereas Sledsens is painting from Monet, and his own imagination. But the result is sincere, a dream image rather than a post-modern mash-up, or art history as a playground. This is perhaps the secret of Sledsens’ appeal: he taps into his own longing, creating a utopian world in which he would like to live. Then he offers to share that world with us.