Bendt Eyckermans’ Sculpted Paintings

Despite being so young, Bendt Eyckermans (b. 1994) already has a number of solo exhibitions to his name and his work is sought after by collectors all over the world. Yet the painter from Antwerp remains humble. Eyckermans understands that he still has a lot to learn. ‘I think it’s important for an artist to have knowledge of everything that has come before them’.

Hilde Van Canneyt: Is it true that you don’t like to talk about your paintings? We’ve got a problem if that’s the case.

Bendt Eyckermans: ‘No, I quite like to talk about my paintings and the way in which I paint, but I don’t enjoy talking about the deeper meaning that is supposedly hidden behind them. I think it’s important that the viewer isn’t primed too much. I hope to be able to stimulate the spectator’s mind, so they themselves can call on associations and make their own story. My visual language is in itself very clear, my paintings are no great enigmas.’

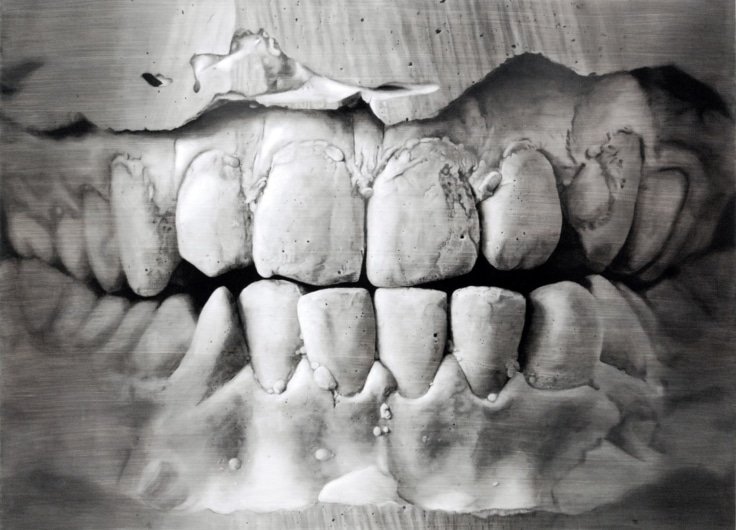

Bendt Eyckermans

Bendt Eyckermans© Antwerp Art

Which creations formed you as a child?

‘The pieces of art in my family will have definitely influenced me from day dot, but it was only when I was eight or nine that I became explicitly aware of those things as unique objects and pieces of art. The first piece of “art” that really interested me was something I made myself. At pre-school we were asked to copy pieces of art. I remember a charcoal drawing on coloured paper on which I had copied Permeke. I actually still have that drawing. I still remember the fascination I had for what I was copying: mainly depicting those huge hands and feet in Pemerke’s drawings, and also how pleasant I found it to copy it.’

You grew up amongst your father’s and grandfather’s sculptures. You also work in their former studio. It’s still full of their sculptures here. That’s an inheritance that you can’t easily shake off, when did you choose to go into art yourself?

‘When I was about 16 I went to art school in the hope that I could develop my drawing. I also enjoyed more freedom there. Unlike the other schools I had been to, I felt comfortable at art school and that was largely down to the people that I met there.’

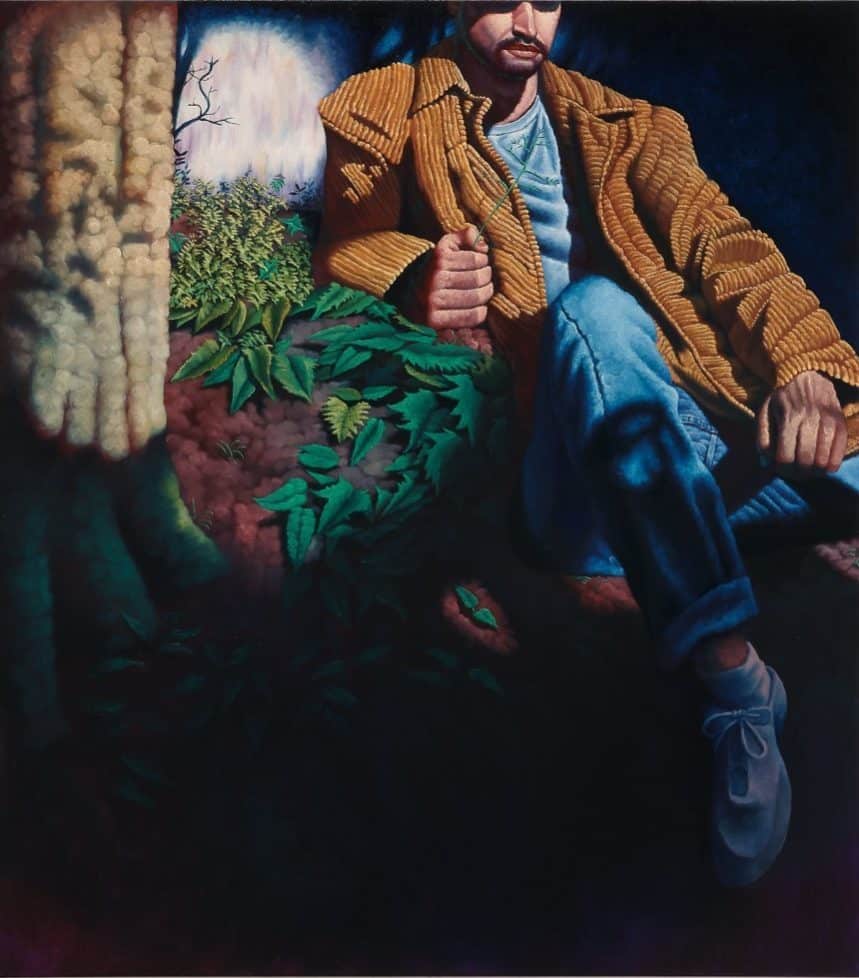

Bendt Eyckermans, A lover's sight, 2018

Bendt Eyckermans, A lover's sight, 2018Why did you choose not to study sculpture at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts when you were 18? Was it that you liked colour in a two-dimensional sense, or did you think continuing the work of your grandfather would be too much of a good thing?

‘Before I started at the Royal Academy colour was something I couldn’t really understand. I mostly made drawings that were very graphically tinted. I just didn’t get painting. When I got to the Royal Academy I learned about the application of colour through looking at The Old Masters. How I could make the right use of colour to turn a sketch into a beautiful whole – to a composition in colour and form.’

Were you already interested in twentieth century painting during your studies or did that happen after you had finished?

‘Inter and post-war art and specifically New Objectivity, are areas of art that have always stimulated me. I have learned a huge amount from these strands and have a lot of respect for them, especially because those artists were brilliant at documenting the time that they inhabited. I found that really inspiring to be able to apply to my work. Thanks to the Royal Academy, my taste within strands of art has been widened enormously. I became acquainted with Jean Brusselmans, whose technique has taught me to paint impasto. He ‘taught’ me about how to apply paint, about the shape of his brushes, and how I could paint a body in a geometric way.’

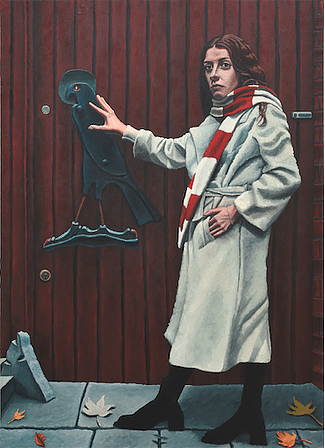

Bendt Eyckermans, Morning Light, 2019

Bendt Eyckermans, Morning Light, 2019I recognise the artist Octave Landuyt from Ghent in your work, and the lesser known brothers Floris and Oscar Jespers are also role models for you. You study the technique of The Old Masters – all the way to Rubens – to become stronger in your own visual language.

‘I think it’s important for an artist to have knowledge of everything that has come before them. It’s from the images my grandfather created that I learned how a nose or lips are formed. I also enjoy integrating elements of sculpture into painting. Many people are of the mistaken opinion that you have to have that 70s avant-garde mentality, and that you have to be radical. But art actually doesn’t have to be anything at all. For me, something is a piece of art when it stimulates someone and makes them think, when it lives on in the thoughts and fantasies of an individual. A creation isn’t necessarily a piece of art just because it’s finished. I could just as well leave my works in my studio, but that wouldn’t help the world at all.’

You paint everyday life. The characters of people from your life. They are sometimes called anti-heroes. Through your paintings we get to know your friends and family, and also you better. Typical traits in your characters are the introverted looks, painted in a kind of constrained space, sometimes surrounded by a kind of blue haze.

‘I do use my friends, but I also use mannequins. I’m not really making portraits of them. The people in my paintings are just figures who help to create the image. My works are often about atmosphere and feeling, and I daresay the Zeitgeist of my generation. I also like working with actions that can seem dubious, that carry in them something both passionate and aggressive.’

Bendt Eyckermans, Where we'll meet, 2018

Bendt Eyckermans, Where we'll meet, 2018Are your works a composition of images? How do you go about starting your work?

‘I take various photos of moments or of friends who I ask to come and sit for me in the studio. Then I’ll build a construction to stage the light. I make up things like the background or the location. The photos act as a kind of source for the coincidences that I can’t make up – like the folds in a shirt. Certain elements then change into something symbolic.’

Earlier you mentioned that for you, a painting doesn’t have to be full of meaning. Would abstract painting not be of any interest to you then?

‘No idea. Never say never, but at the moment it wouldn’t give me satisfaction. In the sense of painting techniques, you can do interesting things. There are painters who make fantastic abstract works. Like Cy Twombly, who makes beautiful paintings full of feeling, and that feeling is something that does fascinate me.’

What is it in other painters that inspires you most?

‘That’s different with every painter. But when I look at a painting, I always look at how the paint is applied, and I study the use of colour. You can pretty much see straight away if someone has worked with an interesting colour palette. As well as that I like to look at how coincidences steer the creation, or how an element can hit the right chord by being placed in the perfect location.’

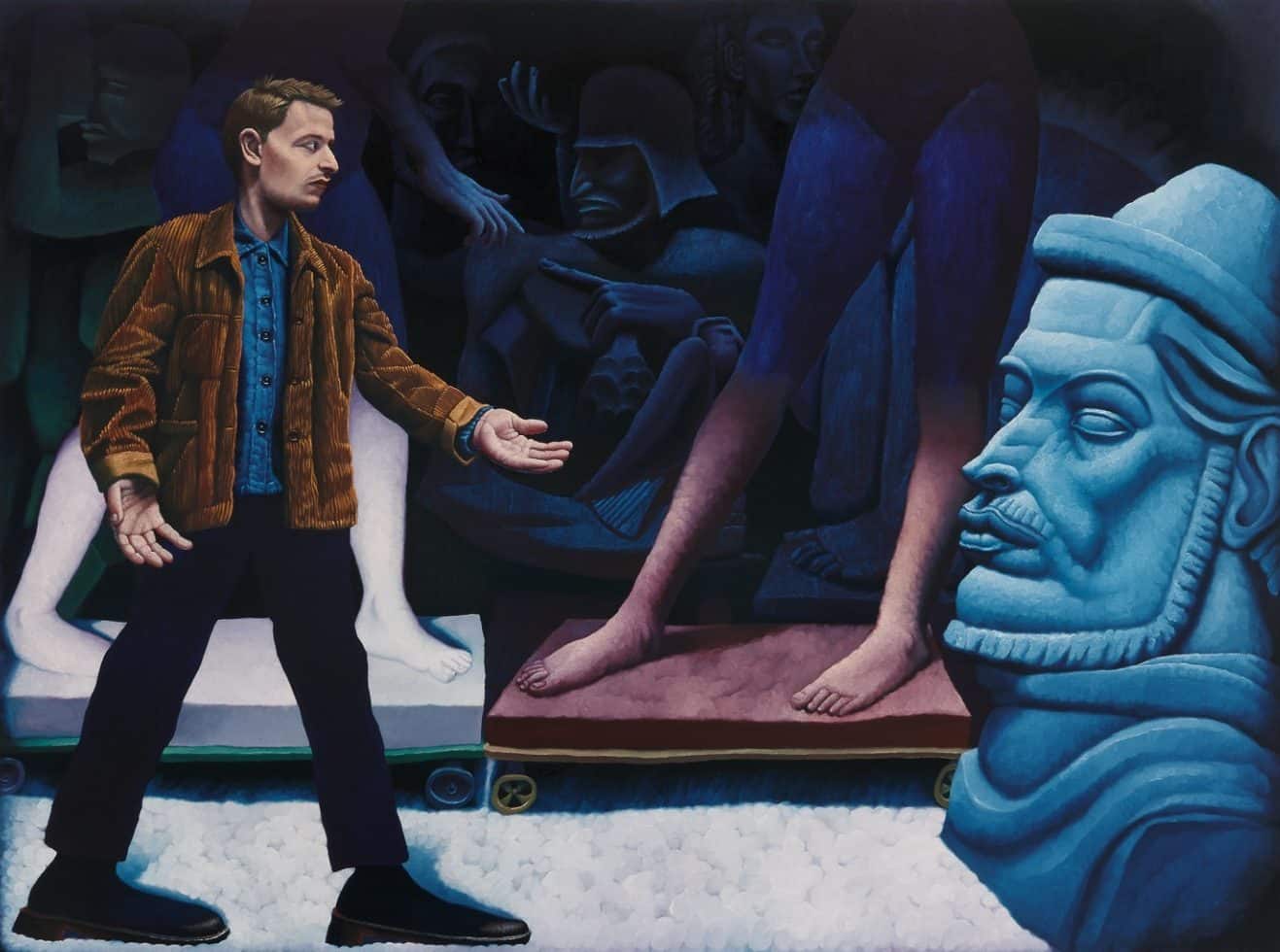

Bendt Eyckermans, Conversation with a Statue, 2019

Bendt Eyckermans, Conversation with a Statue, 2019Do you think that being creative is painful?

‘Everyone has their off-days. I think it’s fine to occasionally go to the studio and just sit and read and think. I experience that as moments of reflection, to take a step back and develop my thinking and to arrive at new perspectives. I do think it’s important to have structure and to go to my studio at regular times. It’s a kind of anchor. If I don’t, it can have a negative impact on my thinking.’

Do you want to convey a societal message with your images?

‘No. I don’t think you can fix societal problems through processing them in paintings. Honestly, I actually think it’s pretty pretentious to think that you can improve the world with a painting. I’m not a painter who feels compelled to express political or societal criticism. I’m concerning myself with the world that I live in, with the people that I like, and what I think is interesting. I think the story of my family history is also fascinating to work with.’