Biodesigner Emma van der Leest is Growing a Sustainable Future

Living organisms like bacteria and algae could potentially embody environmentally friendly production processes: you can literally use them to grow new materials. Dutch biodesigner Emma van der Leest (b. 1991) studies how she can use these organisms to create durable materials. Her work is part of the group exhibition Polarities, on show at MU in Eindhoven until 1 March 2020.

Walking into BlueCity in Rotterdam for the first time is an almost surreal experience: the large, open space is immediately recognizable as a former swimming pool, but without water. Abandoned for years, the building has housed a range of environmentally conscious enterprises since 2015, amongst which Emma van der Leest’s BlueCity Lab: a creative laboratory where she and her peers are building a sustainable future.

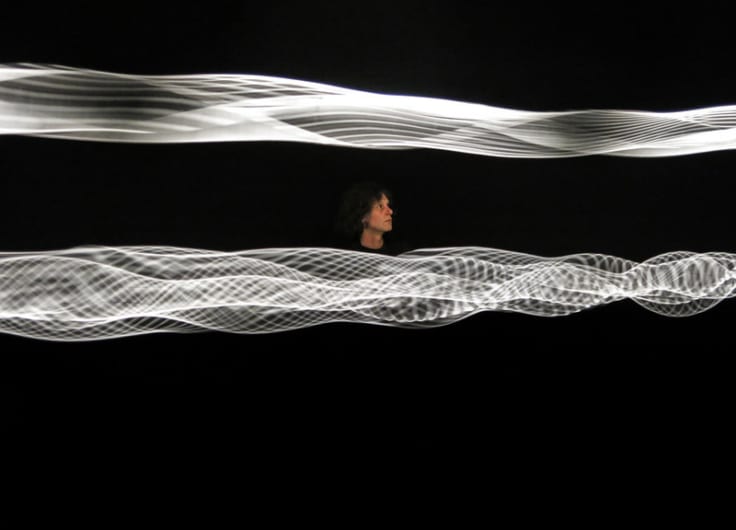

Emma van der Leest in BlueCity

Emma van der Leest in BlueCityThe building’s transformation is an excellent example of ‘blue economy’. Our normal economy revolves around the commodification of products, for which raw materials are needed. Naturally, this leads to overproduction and waste. Blue economy turns that idea on its head by working on the basis of demand. Surplus materials, waste and things that have exhausted their original function are crucial.

BlueCity is housed in a ‘recycled’ building where various parts have gotten a surprising new function. Other so-called ‘waste streams’ were assigned a place: a large obsolete freezer formally owned by a well-known brewery has become an excellent environment for growing bacteria. Van der Leest is very interested in the practical uses these micro-organisms might offer.

A cellulose jacket

Van der Leest graduated from the Willem de Kooning Academy in 2015 as a product designer. One of her advisors, Guus Vreeburg, noticed how during that time her attention shifted from design to materials – specifically the creative and unorthodox ones.

In 2012 she developed an interest in the oeuvre of Suzanne Lee (b. 1970), a bio- and fashion designer whose sustainable clothes were made using cellulose, produced by bacteria. After seeing Lee’s TED talk, Van der Leest decides to follow her example and grow sustainable materials using micro-organisms. At the time, that meant a lot of research and testing. After securing a coveted internship with Lee, the two women collaborated on a manual aimed to instruct those interested in similar science with their production process.

Emma van der Leest

Emma van der Leest© Menno Boer

These days Van der Leest lectures on biodesign and teaches at the Willem de Kooning Academy and the Design Academy, where she shares her knowledge with others. Sharing and collaborating play an important part in her discipline. Furthermore, she was appointed as a researcher at both the interdisciplinary Biobased Art and Design research group at Avans University (‘s Hertogenbosch) and Rotterdam University.

Biodesign has seen a surge over the last few years, being a hybrid field that cross-stitches science, design, technology and visual art. It is therefore often referred to as bio-art, even though the terms are not fully synonymous. There are often significant compositional differences in ingredients, for example. Some projects are dedicated to product manufacturing. Others are more speculative in nature, often because science hasn’t yet caught up with their futuristic visions, and they lean towards the visual arts. What these projects have in common, however, is an interest in sustainability, the environment, and working with living organisms.

Prototype of 'Growing Materials', a plastic replacement out of fungi and hemp.

Prototype of 'Growing Materials', a plastic replacement out of fungi and hemp.Van der Leest likens biodesign to open source software, which has an exposed course code, meaning programmers can freely access and use it. This often leads to the formation of new communities and collaborative projects. Scientific research is, according to Van der Leest, often too competitive and driven by a rat-race mentality, while artistic researchers like herself are more geared towards collaboration. Again, BlueCity is a good example: it hosts many ‘free’ companies that work on their own, autonomous projects, but they often borrow each other’s equipment, exchange ideas and – according to the ethics of blue economy – they make good use of each other’s surplus and waste materials.

Compostable materials

One of Van der Leest’s projects is the book Form Follows Organism. The Biological Computer (2016, Willem de Kooning Academy) which, fittingly, is hybrid in nature itself. It is both a research publication, a personal reflection on biodesign and a statement on the role designers will play in the future: ‘Eventually, it is the task of designers to discover how sustainable materials, derived from nature, can become the commodity products of the future.’

This quote exemplifies Van der Leest’s commitment to long-term thinking, of looking at the future while keeping an eye on the present – because steps have to be made, right now. Over time, she has produced several biologically derived materials, often in collaboration with others, including a plastic replacement out of fungi and hemp.

The project is called Growing Materials (2015, with Zoë Agasi and Loeke Molenaar): a title that already implies how little you need to create a material like this. What is more, the product is easily composted when its use runs out – contrary to those artificial materials that will increase pollution in the near future.

In Form Follows Organism, Van der Leest expands on the importance of seduction and storytelling. Attention is often drawn by an attractive but seemingly ordinary object. An example is Biocouture Bag (2014), a satchel made of bacteria-derived leather, which she likes to show as a conversation starter. This is then followed by an explanation of its production process and how it can be composted.

Sustainability and environmental questions are often abstract, difficult topics for many people, but by rendering them concrete and tangible the conversation soon starts to flow. Storytelling is a big part of this: presenting a narrative that makes the product or idea, and its foundational ethics, concrete and relatable. It is a smart strategy, especially when it concerns not (yet) realisable, speculative projects.

The 'Biocouture Bag', a satchel made of bacteria-derived leather

The 'Biocouture Bag', a satchel made of bacteria-derived leatherThese days, the practical applications for bacterially derived leather seem increasingly realistic: thanks to a fungus-based coating that produces water-resistant spores. To create this protective layer, Van der Leest and biologist Aneta Schaap-Oziemlak are collaborating with Radboudumc researchers Paul Verwij and Sybren de Hoog. The research was made possible through the BAD Award (‘Bio Art and Design’): a prestigious development grant aimed to help bio-artists, designers and scientists realise their plans.

This project, The Fungkee Supercoating, is on view at MU (Eindhoven) until 1 March 2020, as part of an exhibition designed as a futuristic concept store.

Vending machine of the future

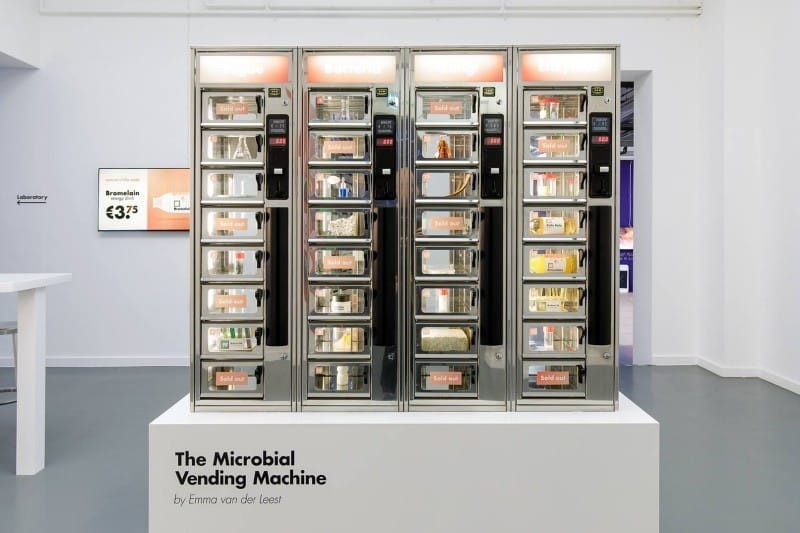

The fact that the future is much closer than we think is also evident in The Microbial Vending Machine (2019), a work Van der Leest submitted when nominated for the Dolf Henkes Prize 2019. The project consists of two parts in which seduction and storytelling play an important role. First, there is the quintessential Dutch vending machine but, instead of croquettes, it holds products made out of microbes. Many of these already have practical uses, like building material derived from fungi, but others are still theoretical in nature. For example, the potential probiotic functions of the E.coli bacteria have already been discussed, but their practical application has yet to be realised.

The Microbial Vending Machine

The Microbial Vending Machine© Aad Hoogendoorn

The project was first on view in 2018, at the Rotterdam-based exhibition space TENT. Within seconds, you were able to traverse from the vending machine to a lab, which had Petri dishes on show. The separation between everyday life and science was minimal, as the distance between man and nature. Eventually, the goal is to make microbial products as accessible as an everyday snack. It is hard to resist the temptation of throwing in a coin and pulling open one of the small doors.

Although Van der Leest describes The Microbial Vending Machine as a speculative and ideological rather than practical in nature, the project sets out a tantalizing potentiality in which many things converge: research, microbial processes, and the enhancement of environmental consciousness.

The Microbial Vending Machine

The Microbial Vending Machine© Aad Hoogendoorn

It is as though she is outlining a future that she and her peers, both from within and outside of BlueCity Lab, are working towards. In the end, she is not concerned with thinking exercises or speculation, but rather with ensuring the application of sustainable materials on a large scale. This requires a lot of work and trials, says Van der Leest, but it simply has to happen.