Bīru and Kōhī Are Not the Only Japanese Words Dutch Speakers May Understand

The Dutch language was for some time the lingua franca between Japanese and Europeans. Today, there are still well over 150 Dutch loanwords in common use in Japanese and many more words, such as the grammatical terms, which owe their origin to Dutch.

The Dutch language crashed onto the shores of Japan in 1600 aboard the ship, De Liefde (‘Love’), which had set out two years earlier from Goeree in Holland to establish trading relations between the nascent Dutch Republic and Japan. Over the course of the next 250 years or so, Dutch would become the dominant European language in Japan, being used in speaking and writing and as a source language for over 1,000 translations into Japanese.

Replica of the galleon "De Liefde" at Dutch theme park Huis Ten Bosch in Nagasaki, Japan

Replica of the galleon "De Liefde" at Dutch theme park Huis Ten Bosch in Nagasaki, Japan© Wikipedia

In 1609, the Dutch, now under the flag of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), were granted the right to trade through the port of Hirado on the island of Kyushu. Here, they vied with other Europeans such as the Portuguese and, briefly, the English, to profit from importing and exporting goods between Japan and Europe and elsewhere in East Asia.

The Portuguese had been in Japan since around 1550, but their attempts to convert Japanese to Catholic Christianity met with increasing opposition and in 1639 they were expelled. The Dutch were then forced to move to Deshima, an artificial island in the Bay of Nagasaki. Here, they traded with the Japanese, the only Europeans allowed to do so until 1854, when the American Commodore Perry forced Japan to open trading relations with the USA and other European countries.

Deshima (in the background) was a man-made island in the port of Nagasaki, which served a Dutch trading post located in Nagasaki from 1641 to 1854.

Deshima (in the background) was a man-made island in the port of Nagasaki, which served a Dutch trading post located in Nagasaki from 1641 to 1854.© Wikipedia

Initially, the Japanese with whom the Dutch had contact were interpreters, local officials and merchants. One exception was the Shogun and his courtiers, whom the Dutch had to visit at Edo (now Tokyo) every year to show their gratitude for being allowed to remain in Japan. Gradually, however, Japanese intellectuals came to realize that some of the knowledge that the Dutch brought with them, in particular in the fields of medicine and astronomy, could be of use to them.

Scholars started to engage with the Dutch, asking for books which they began to translate into Japanese. For several reasons, Japanese often did not speak Dutch particularly well, with the Dutch often commenting disparagingly on this. Some Japanese, though, managed to write quite decent Dutch. A feudal lord, Kutsuki Masatsuna, corresponded with the head of the Dutch trading post, Isaac Titsingh, on subjects of mutual interest. Endearingly, Kutsuki would ask Titsingh to correct and return his letters.

Kutsuki Masatsuna (1750-1802)

Kutsuki Masatsuna (1750-1802)© Wikimedia

A few Japanese words found their way into Dutch. One was soja (‘soya’) from the Japanese tsu. This subsequently entered many other European languages including Frisian and English. Others were sake and moxa or moksa, a medicinal herb used in acupuncture. However, most of the traffic went in the other direction.

Possibly the first Dutch word that the Japanese adopted was kok (‘cook’), in 1615. The Dutch words borrowed by Japanese typically underwent changes and this word was rendered kokku. Words for food and drink which the Dutch brought to Japan made the same journey. One example is koffie (‘coffee’). This was adopted as kōhī. Such words are written in the Japanese katakana syllabary, which underlines their foreign origin. This has subsequently been combined with English words to provide kōhīshoppu (‘coffee shop’) and kōhīkappu (‘coffee cup’).

A can of beer

A can of beerIf you go into a bar in Japan, you can order a bīru, i.e., a beer, from the Dutch bier. In the early nineteenth century, the Dutch word for ‘potatoes’ aardappel(s) appears in a Japanese text as aarudoappereso. This has since been replaced by jagaimo, literally ‘Jakarta tuber’, reflecting the fact that the Dutch imported potatoes from Jakarta (Batavia).

Unsurprisingly, Dutch shipping terms have been adopted by Japanese. These include dekki

(Dutch dek, ‘deck’), dokku (dok, ‘dock’), masuto (mast, ‘mast’), and tarappu (‘ship’s ladder’ or ‘gangway’) from the Dutch trap (‘staircase’). The Dutch word for ‘sailor’, matroos, has been adopted by Japanese in several phonetic variants such as madorosu.

In some cases, the Dutch influence is harder to detect, e.g., in translation loanwords. Many grammatical terms fall into this category. For example, the Dutch word for ‘noun’ is (zelfstandig) naamwoord, literally ‘name word’. Japanese translated this literally as meishi. These Japanese grammatical terms would in turn be adapted and adopted by Chinese and Korean. Indeed through contact with the Japanese in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, both Chinese and Korean imported several Dutch words via Japanese. Chinese adopted gas ‘gas’ as wǎsī, while the Korean word for ‘bag’ kabang

can be traced back to an older Dutch word for ‘basket’ or ‘sack’, kabas.

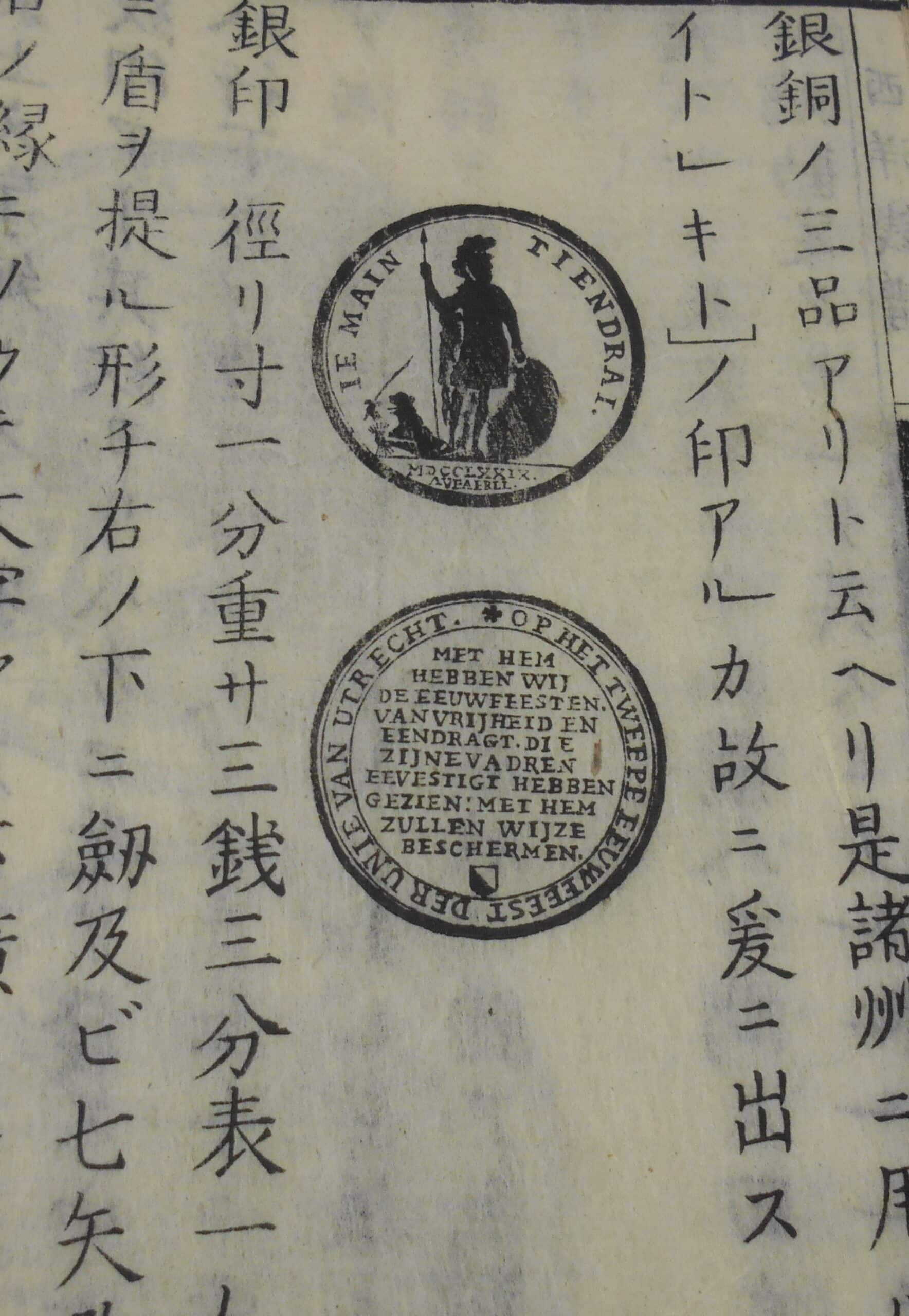

A Dutch coin in Kutsuki Masatsuna's book on Western coins

A Dutch coin in Kutsuki Masatsuna's book on Western coins© Christopher Joby

In the late eighteenth century there was a real craze for things Dutch in Japan. This led to the word for ‘Holland’ Oranda (actually from the Portuguese) being attached to anything vaguely Western, or even foreign. Oranda-peki denoted those crazy about things Dutch, Oranda-ichigo

‘strawberries’, and Oranda megane-e Western ‘peep-boxes’. The middle syllable of Oranda was also used extensively, most notably in rangaku, literally ‘Dutch studies’, though it covered Western learning in general.

The Japanese interest in Dutch science led to the adoption of many loanwords in this field. For example, the Dutch word for the ‘appendix’ in the stomach is blindedarm, which literally means ‘blind intestine’. Each part of this word was translated into Japanese giving mōchō, which also literally means ‘blind intestine’. Variants on this entered Chinese and Korean. The Japanese term for the ‘Leyden jar’, an early sort of electric battery, is Raiden-bin, a combination of the Dutch place name and the Japanese word for ‘jar’.

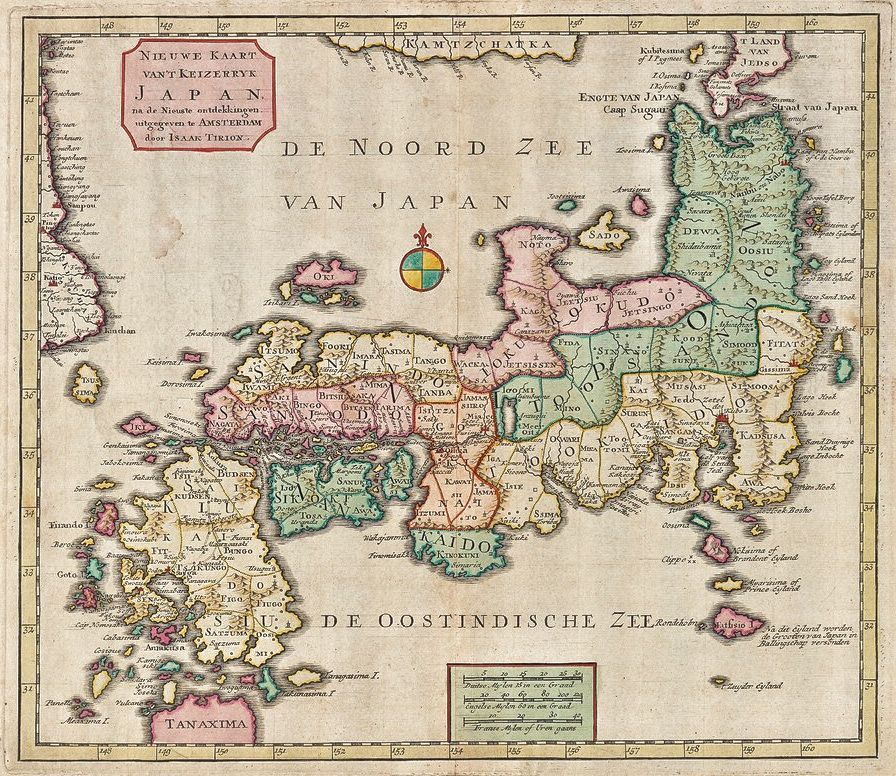

Antique Dutch map of Japan. "Nieuwe Kaart van't Keizerryk. Japan na de Nieuste ontdekkingen", 1740?

Antique Dutch map of Japan. "Nieuwe Kaart van't Keizerryk. Japan na de Nieuste ontdekkingen", 1740?But it was not just the vocabulary of Japanese that was affected by contact with Dutch. When translating Dutch texts into Japanese, translators sometimes needed to develop new words and particles to deal with the grammatical differences between the languages. One example is the relative pronoun tokoro no (‘which’), still in use today.

After 1854, there was an initial surge in Dutch, for it was used as a lingua franca between Japanese and Europeans. However, when the Japanese realized there were bigger and more powerful countries in the world, the use of Dutch declined sharply and by 1900 its use in Japan had become very limited. Nevertheless, there are still well over 150 Dutch loanwords in common use in Japanese and many more words, such as the grammatical terms, which owe their origin to Dutch. When Dutch speakers visit Japan, they can perhaps think back to the time of significant Dutch influence on Japanese when they order a coffee, or a beer – bīru-o kudasai!

Christopher Joby, The Dutch Language in Japan (1600-1900), Brill, Leiden, 2020, 494 pp.