Black Holes: ‘Habitus’ by Radna Fabias

It does not often happen that critics unanimously proclaim a poetry debut a masterpiece, but Habitus (2018) by Radna Fabias was quite rightly welcomed as a mature and surprising book. Her poetry collection has won all major poetry awards in the Netherlands and Belgium, including the Herman de Coninck prize and the Grote Poëzieprijs. Habitus has recently been translated into English.

Fabias (b. 1983), was born in Curaçao, studied at the College of the Arts in Utrecht and had been writing poetry for years, but delayed publication until her work was top quality. In May 2018 she was awarded the C. Buddingh’ Prize for Habitus: it can seldom have been so easy for a jury to identify the best candidate.

Radna Fabias

Radna Fabias© Elizar Veerman

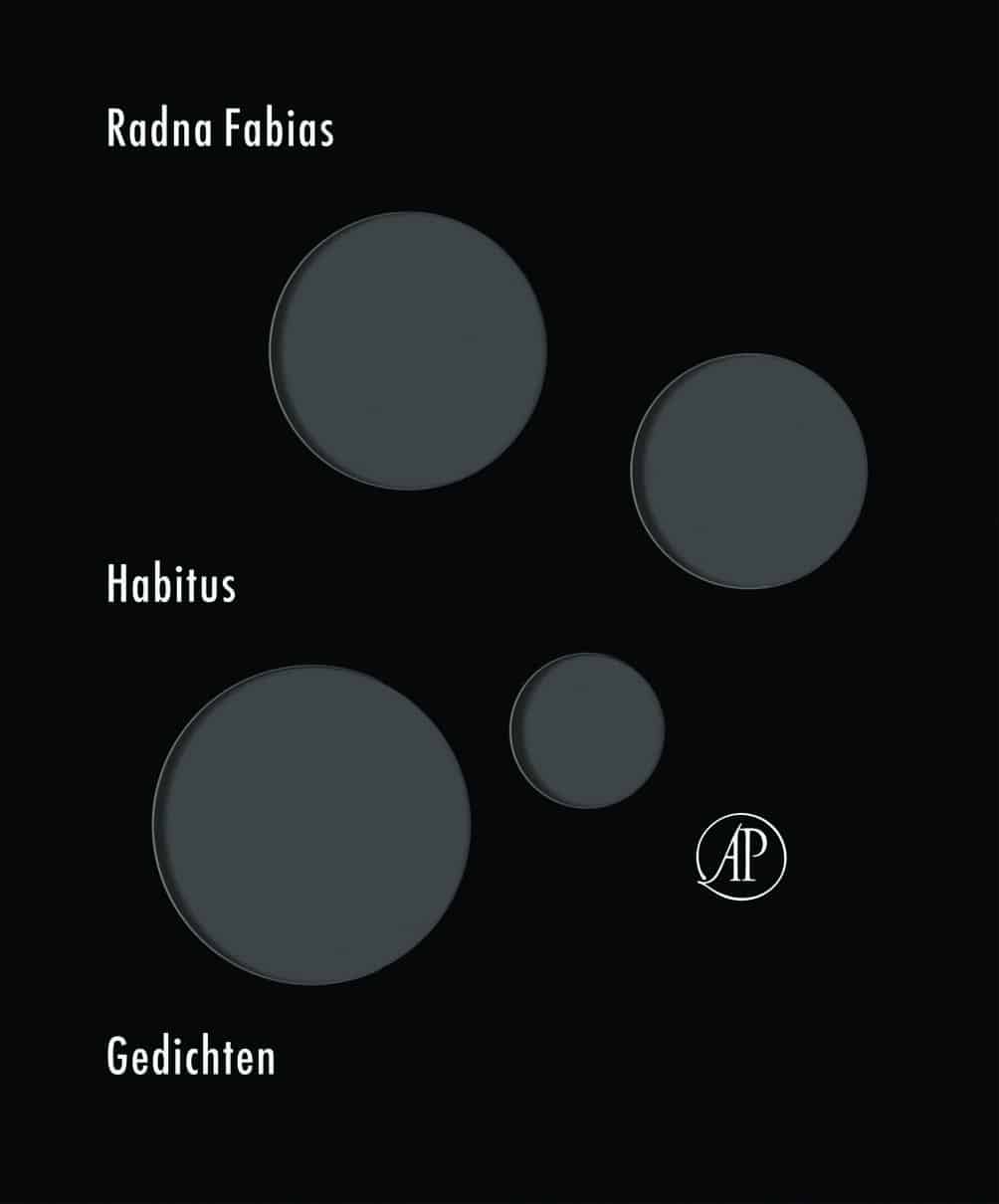

The design of the original Dutch book is remarkable in itself. The cover is black with white lettering, but four round holes have been made in it, revealing an anthracite-coloured end paper. We look through the black only to encounter another black shade. The sections in the bulky collection are separated by black pages. With a poet who emphasises her Caribbean origins, that has to be a statement. Halfway through the collection there is a poem entitled ‘the blackness of the hole’ which begins as follows:

black holes are weird

black holes are the strangest

objects in the universe

The gravity in this area is ‘black / very black and strong / so strong nothing can escape it’. The astronomical phenomenon here stands as a symbol of unfathomable mysteries with an irresistible attraction. Perhaps poetry itself is such a mystery, but everything connected with sexuality, ethnicity and religion also falls under it. What do we know of ourselves and the world? And how do we express what we experience without selling the mystery short?

Cover of the Dutch edition of Habitus

Cover of the Dutch edition of HabitusThe title Habitus points to an attitude to life, possibly hard-won, a consciously adopted position that enables the poet at once to experience and observe the incoming stream of confusing impressions. Fabias is an involved observer, who at the same time manages to allow herself to be carried away and in so doing to carry the reader along with her, while maintaining a critical distance. The work is lyrical, rhetorically effective, alternately tender and rock hard and here and there also very funny. The tension between surrender and distanced reflection is definitely connected with the sense of living in at least two worlds. In one of the poems a returned migrant prays for the neutralisation of his feeling of dichotomy – probably in vain.

The collection opens with an evocation, six pages long, of the arid island with which the poet feels connected, while she nevertheless reveals its problematic side. The rhythm is free and insistent, the lines vary enormously in length and stanzas which begin at the left-hand margin are answered by passages that are aligned on the right. The sentences develop fugally, or perhaps one should compare the technique to a relay race, in which one word-group always hands the baton om to the next. For instance, the collection opens

rims

the impeccably polished rims shining in the sun

too big and too expensive for the cars they spin under

the tinted windows of the cars with the shining rims

the almost horizontal drivers of the cars with the tinted windows and the shining rims

Step by step a slowly swinging world is evoked of dusty roads with potholes in their surface, drunken men who make plump girls pregnant, churches the colour of ripe bananas, Spanish-language soaps and irritating tourists, all this under a merciless blue sky.

In most poems Fabias makes abundant use of repetitive tropes. That is interesting, because she writes about cultural patterns which reproduce themselves from generation to generation, despite people’s longing precisely to escape from them. Several times Fabias writes about mothers and grandmothers who tenderly and dominatingly hammer on the importance of procreation, though they themselves experienced more grief than joy from it. In the last poem the poet determines solemnly not duplicate her mother’s behaviour:

because i love my mother i ward off repetition

from my clamped ovaries

my clamped ovaries are clean

my clamped ovaries are magnificent

my clamped ovaries are made of reactive metals

It is a painful paradox that the repetition is renounced in the form of a pounding anaphora.

Naturally we find pernicious patterns that are hard to break wherever people try to get on with each other. Rich is opposed to poor, men treat women carelessly as sex objects, racism is ubiquitous. With the astonishment of a relative outsider Fabias sketches the politically-correct world of thrusting two-income families and mums on their delivery bikes. There is deadly humour, for example, in a text printed as a survey, where one can answer the questions with yes or no. The list contains, among other things, the following items: ‘festivals overseas travel cerebral secularized meditation weekend mind-expansion […] polyamory […] crippling nuance […] photographing meals’.

However, the laughter dies on your lips with the poem ‘demonstrable effort made’ which describes the suffocating norms which a would-be Dutch citizen is expected to internalise:

the applicant can ride a bike without training wheels

knows how to adjust clothing to the meteorological conditions

can go outside without a coat when it is 60 degrees

uses the hips less when dancing

If these are externals, further on in the poem it is really a matter of how you must think: ‘doesn’t know what the people who have fled should do either / is broadly socialized’ and ‘has moderated her tone / controls the anger / has pointed the finger at herself’.

Cover of the English edition of Habitus

Cover of the English edition of HabitusSo Habitus is a political project through and through, and in that respect Fabias fits into a new movement of young, self-confident, “black” poets who explicitly address injustice in the shape of racism and sexism, such as Simone Atangana Bekono (How the First Sparks became Visible, Lebowski, 2017) and Dean Bowen (Bokman, Jurgen Maas, 2018). It is high time that such topics were raised in Dutch poetry. But that is not the only reason why Habitus should be embraced (although that could be a legitimate motivation in itself). No, it is the élan and the rhythmic drive, the richness of the imagery and the subtlety of the vision of human existence that make this great poetry.

Dutch edition

Radna Fabias, Habitus, De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam, 2018. 118 pages

English edition

Radna Fabias, Habitus, translated from the Dutch by David Colmer, Deep Vellum Publishing, Dallas, 2021. 112 pp.