Blue Blood, Sweat and Tears: Nobility in the Low Countries

Together, Belgium and the Netherlands have 46,000 aristocrats. Many people still imagine that the nobility are rich, somewhat unworldly figures who live in beautiful castles with vast estates and spend their days in dolce far niente. However, the days when the nobility could live off their investments or the proceeds of their estates are gone. They have had no choice but to adapt their lifestyles. Yet many still endeavour to go through life as grand seigneurs. An intriguing portrait of the Belgian and Dutch aristocracy.

Those of noble birth are saddled from the start with a world of traditions. True aristocrats try to live according to the ‘Ten Commandments’ of their rank: honour and loyalty, devotion to the sovereign, fatherland and fellow man, courage and sacrifice, respect for the sacred, charity, courtesy, family ties and simplicity in social contacts. Outsiders may already smile pityingly at the enumeration of the code of honour that Duke Pierre-Marc-Gaston de Lévis labelled noblesse oblige in 1808. Still, for true nobles, these are not outdated notions. However old-fashioned they may seem, the ideas and customs associated with nobility live on.

‘If there is one thing that old nobility abhors, it is vulgarity. In general, we live very simply,’ says Viscount Yves de Jonghe d’Ardoye. ‘An aristocrat must be humble at heart. All that matters is richesse de coeur. A noble title is a sort of international licence, a sort of credit card that opens doors for you all over the world. Belonging to the aristocracy doesn’t bring any special material benefits, but you are part of a network of friends and relations that you can always fall back on. Like Free Masons or the mafia.’ For noblewoman Dr. Nathalie van de Werve de Vosselaer, nobility is more than anything a state of mind. ‘It certainly isn’t immense wealth and power with country estates and castles anymore’. Prince Charles-Louis de Mérode, a Knight of the Golden Fleece and publisher of the Carnet mondain (social notebook), the Belgian equivalent of Debrett’s Peerage & Baronetcy or the now defunct Burke’s Peerage in Britain, and the USA’s Social Register, puts his status in perspective. ‘I inherited my title from my ancestors, and I’ve passed it on to my children. But personally, I think that meritocracy, achieving something in life through your own talents or merits, is more important than aristocracy.’

Princess Clotilde and Prince Charles-Louis de Merode

Princess Clotilde and Prince Charles-Louis de Merode© Fondation Merode-Rixensart

From princes to squires

The roughly 35,000 noble Belgians are scattered across some 1,200 families. Their personal details, addresses and relationships can be found in the Carnet mondain and Highlife de Belgique (‘Belgian high life’), the bibles of Belgian high society.

The Belgian nobility comprises three groups, aristocrats of the ancien régime (approximately 30 percent), nobles who received their titles from King William I of the Netherlands, and those ennobled by the seven successive Belgian monarchs. In terms of rank, the members of the high nobility – princes (9), dukes (5) and marquesses (5) – are at the top, followed by representatives of the lesser nobility – counts (about a hundred), viscounts (450), barons and knights (several hundreds). Around 400 noble families have no title, but sometimes an entry as écuyer or schildknaap (squire). Such men are entitled to be addressed as jonkheer in Dutch, or to have their name followed by écuyer (Ec.) in French, the equivalent of the British Esquire (Esq.). Female members of a squire’s family may be addressed in Dutch as jonkvrouw or freule, or ma’am in English. A noble title is considered to be part of a person’s identity and must therefore be entered on all official documents.

The difference between high and low nobility has largely disappeared

The difference between high and low nobility has largely disappeared. Seniority counts for more than the title. In any case, nobles like to present themselves to the outside world as ordinary people. Although some of them assume an attitude that suggests that in the deepest fibres of their body, they feel far superior to ordinary mortals. ‘Correction,’ says Count Boudewijn de Bousies de Borluut, whose family tree dates back to the eleventh century. ‘We don’t feel we are better than the masses, but we do try to be better. We’re spoon-fed that from the cradle onwards.’

‘The reward comes after the battle’

Apart from marrying a nobleman (‘bed nobility’), there are three ways of joining the nobility. One can have an existing title recognised, like the knight Jean Breydel de Groeninghe, one can be incorporated as a member of foreign nobility, like the Bohemian Prince Stéphane de Lobkowicz, or one can be ennobled by the king for outstanding merit, which is what mostly happens.

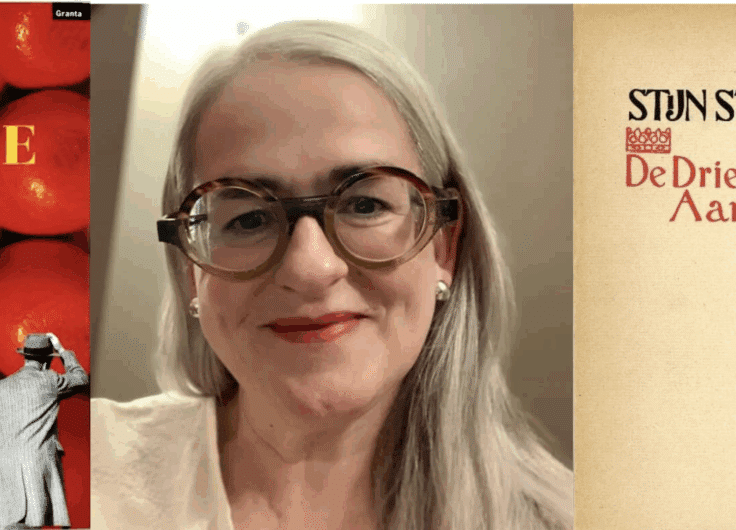

Writer Monika Van Paemel was raised to the peerage in 1995, becoming the first woman in Belgium to obtain the title of baroness in her name.

Writer Monika Van Paemel was raised to the peerage in 1995, becoming the first woman in Belgium to obtain the title of baroness in her name.© Wikipedia / photo Michiel Hendryckx

Belgium, Spain and Great Britain are the last European countries where the heads of state still exercise their prerogative to raise citizens to the nobility. Every year, on the eve of the national holiday, the Belgian Official Gazette publishes a list of a dozen Belgians who have the blessing of the monarch to go through life as nobles. Initially, the king made his choice alone, but since January 1978 he has conferred titles based on the proposals of an advice commission. The commission meets once a month to vet candidates. However, in the case of the writer Monika Baroness van Paemel, the vetting was apparently not done very thoroughly. The royal advisors only noticed afterwards that the writer had posed naked for the cover of one of her books – ‘in a position unworthy of a baroness’.

The new nobles are mostly barons or knights. For women, the lowest title is baroness. Titles are personal and in principle not hereditary. But nobility is passed on to one’s heirs. Axel and Sabrina Merckx, for example, the children of the former iconic cyclist, now Baron Eddy (whose maxim was ‘after the battle comes the reward’), are not baron and baroness but they are entitled to be addressed as jonkheer and jonkvrouw, (or in English, Axel Merckx, Esq. and ma’am).

Hamburgers and caviar

Every year the Association of the Nobility of the Kingdom of Belgium (VAKB/ANRB) organises a reception at which members of the old and new nobility can fraternize. A laudable initiative which, nonetheless, can never completely break down the barriers. Some old-school aristocrats are anything but happy with the inflation of titles. ‘The difference between old and new nobility is the difference between caviar and hamburgers,’ says one of them. ‘When you see the people who get a title, you wonder whether the court always knows who they’re giving them to.’

Obviously, some high-class people deserve to be among the country’s elite. They belong there in any case, even without a title. New nobles ought really to take an exam and be tested on how they intend to carry out our code of honour. That would rule out nobility for certain people of whom the Italians would say: E veramente duce, ma non cavaliere. In other words, he may be a duke but that doesn’t make him a gentleman.’ Or, as Edmund Burke put it: The king creates noblemen, but not gentlemen.’

Aristocracy and dynasty

Although there are, increasingly, exceptions, the Belgian aristocracy is predominantly conservative, Catholic, royalist, patriotic and in certain cases rabidly French-speaking. The royalism of the nobility is a historical fact in Belgium. Aristocracy and dynasty are traditionally allies. The monarch is the country’s number one noble. In the old days, the members of the high nobility were received separately at the palace, in the Salon bleu (Blue Room).

In the old days, in Belgium, the members of the high nobility were received separately at the palace, in the Blue Room.

In the old days, in Belgium, the members of the high nobility were received separately at the palace, in the Blue Room.© Wikipedia

Devotion to the monarch and fatherland has traditionally translated into careers in the army, at court, in diplomacy, the magistrature or politics. Until the Second World War, the nobility had a major influence on Belgian politics and society life. Many families were represented in the Chamber and Senate or made careers as ambassadors, chairmen, ministers, clerics, Lord Chamberlains, court dignitaries, generals, officers or mayors. Nowadays, though, this is less and less the case.

Poor souls with a castle

For centuries the nobility has been associated with wealth and castles. ‘There are many prejudices about us. They hear your name or your title and immediately think that you’re a cousin of the king because, after all, he is from nobility as well,’ sighs Count Michel d’Ursel. ‘A castle is not a sign of wealth but of poverty. You’re a poor soul if you’re stuck with a castle. It costs a fortune to maintain one.’

Flanders has about 50 privately owned castles, Wallonia 60. These days, castle life is the privilege of people with more money than aristocratic quarters. Only a limited number of nobles (like the Princes Michel de Ligne, Charles de Chimay and Simon de Mérode or Count Juan T’ Kint de Roodenbeke ) still live on an estate with an ancestral castle. Some let out their castle, as the setting for a wedding, concert hall or film set, in order to pay for its upkeep, or they open the estate to the public – a condition for getting subsidies.

Belœil Castle serves as the main residence of the princes of Ligne.

Belœil Castle serves as the main residence of the princes of Ligne. © Jose Constantino / Wikipedia

Oases of civilisation

Whether they live in a castle or a terraced house, the nobility is often distinguished by their lifestyle. Belgian aristocrats meet each other in select clubs, such as the Cercle Royal du Parc and the Cercle Royal Gaulois Artistique et Littéraire (usually referred to simply as the Cercle Gaulois).

In general, too, the nobility likes objects that reflect tradition, counterbalancing the transience of existence. Hence they prefer to surround themselves with antiques, inherited furniture and costly trinkets. Rather a worm-eaten, sagging Louis XVI divan than a new Ikea sofa.

Charity is a noble duty. A lot of aristocrats serve religious charitable orders like the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta. Every year they organise train trips to Lourdes for the sick and disabled. All the doctors, nurses and carers are of nobility. Travel, accommodation, food – everything is paid for by nobles. But charity is not limited to a pilgrimage to Lourdes. Every weekend the knights visit homes for the elderly, and often they take people with them to the seaside or the Ardennes.

Charity is a noble duty. A lot of aristocrats serve religious charitable orders

Noble charity also extends to assisting needy peers. The Association of the Nobility of the Kingdom of Belgium is a circle of friends grouping 12,000 Belgian nobles. It was created during the crisis period when several noble families were faced with finding cash to pay their debts and/or to provide for themselves. Over the years, a fund has been built up from contributions from wealthy members, donations, and proceeds from rallies, parties, balls, dinners and tournaments. On Sunday 14 May, for example, the annual Castle Tour took place in East Flanders. All the proceeds went to SOLIDARITAS, the auxiliary service of the Association of Belgian Nobility, which awards scholarships and provides assistance to people in difficulty. Most noble families also have their own aid fund that intervenes in cases of high medical expenses or expensive studies. It is not without pride that the association mentions that more than 10 percent of its members have academic degrees.

Prospecting the marriage market

Rally evenings are a typical noble phenomenon. With Highlife de Belgique as their frame of reference, the mothers of noble daughters put their heads together during April and May to organise the rally circuit for the summer and autumn. Once a month – on Friday or Saturday evening – each mother organises a dinner dance in which, depending on the renown of the hostess, some 100 to 300 young people participate, for a fee, in order to prospect the marriage market. Not infrequently, the company is international. Many European nobles are affiliated with the Paris-based CILANE, the European Commission of the Nobility, to which sixteen European noble associations belong.

Marrying someone of one’s own standing is not an obligation but is still often preferred. ‘There is a fine French proverb to explain these marriages within the nobility’, says Viscount René de la Faille de Waerloos. ‘One should marry close to home with someone of one’s own kind. After all, marriage is not an easy institution. But, if you marry someone who has had roughly the same upbringing, someone who shares the same principles and lifestyle, the chances of success increase.’ Nonetheless, what was once unthinkable has long since ceased to be controversial. Even in noble circles, there is unmarried cohabitation, divorce and/or remarriage, without this automatically resulting in expulsion from the clan.

Work ennobles and vice versa

For centuries, the aristocracy adhered to the feudal principle of the praying, fighting, and working class. For a grand seigneur, work was taboo. However, most noble families have seen their estates shrink in recent centuries and have been surpassed in wealth by successful commoners. Today they practice the most diverse professions, from farming to banking. Work ennobles and vice versa. Aristocrats can be found everywhere, but business remains the favourite field of operation. What makes them so sought-after and suitable for top jobs is the fact that, like Viscount Etienne Davignon, for example, they have an international network of relations and make good use of them.

Only 11 percent of the 500 richest Belgian families are noble but, according to the website De Rijkste Belgen (The Richest Belgians), they own 56 percent of the total wealth of these 500 families. The shareholders behind the brewery AB Inbev weigh heavily in this. They are the aristocratic de Mévius and de Spoelberch families, who controlled the Leuven-based brewer Stella Artois, and the Van Damme family, the historical shareholder of the Piedboeuf brewery in Jupille. The two companies merged in 1988 to become Interbrew, the forerunner of AB InBev. Like most super-rich families, the Inbev families have since diversified their wealth into other economic sectors. The richest Belgian, Eric Wittouck, once the owner of Tirlemont Sugar and Weight Watchers, has an estimated personal fortune of 10.8 billion euros.

New rich and old money

Historically, the Belgian and Dutch nobility have much in common, but since the second half of the nineteenth century, they have evolved differently. The Netherlands has some 11,000 nobles in a population of 17.6 million, Belgium more than triple that, with 35,000 in a population of 11 million. This large number is mainly a result of the annual injection of ‘blue blood’ in Belgium, whereas in the Netherlands, with the exception of the royal family, no meritorious people have been raised to the nobility since 1948.

The Netherlands has some 11,000 nobles, Belgium more than triple that

Of the approximately 11,000 Dutch nobles, more than 1,500 adults are members of the Nederlandse Adelsvereniging (NAV, the association of Netherlands nobility), which was founded in 1899. Meanwhile, since 1991, young nobles in the age group 18 to 35 have been able to join the Vereniging van Jongeren van Adel in Nederland (VJAN).

The NAV is the only association of which all members of the Dutch nobility can be members, ‘regardless of faith, gender or financial affluence’. Besides organising informal meetings, events, seminars and liaising with other European noble associations, its main purpose is ‘to provide financial support to those within its own circle who are in difficulty.’ In a way, it is a sort of trade union. Even in noble circles, there are people living on the subsistence minimum, although that does not tally with the image.

Past glory

The names of all the noble families in the Netherlands are listed in the Nederlands Adelsboek, otherwise known as the little red book.

While Belgium is teeming with princes, dukes and marquesses, the Netherlands has hardly any princes, other than those of the Royal Household and the children of Princess Irene and Prince Carlos Hugo of Bourbon-Parma. They were inducted into the Dutch nobility in 1996, with the title prince(ss) of Bourbon-Parma and the predicate Royal Highness.

Marquesses, dukes and viscounts are few and far between. The nobility had its glory days under King William I, who distributed titles liberally. In 1848 the peerage was abolished because the Crown considered that inherited privileges were outdated. The only legal right, which the nobility retained, was to be allowed to use a predicate or a title. There are still fifteen families with the title of duke. In addition, there are families with a duke title that belong to the Belgian or German nobility, like de Limburg Stirum, de Norman d’Audenhove, de Riquet de Caraman Chimay, and de Preud’homme d’Hailly de Nieuport. The title of baron can be found in 92 families but that of knight in only seven families. The majority of the Dutch nobility has no title but uses the predicate jonkheer/jonkvrouw(e), i.e. the equivalent of writing “Esquire” or “Esq.” after a man’s name. Commoners who marry a member of the Royal Household are sometimes ennobled. Pieter van Vollenhoven, the husband of Princess Margriet was not raised to the peerage, but the wives of the princes – all commoners – were.

Chimay Castle has been owned by the Prince of Chimay and his ancestors for centuries, and it is open to the public for tours during part of the year.

Chimay Castle has been owned by the Prince of Chimay and his ancestors for centuries, and it is open to the public for tours during part of the year. © Château de Chimay

Last bastion of decency and civility

In the Netherlands, there are aristocratic balls such as the Wiener Ball and the Diplomatenbal, and clubs for the young elite (Minerva), but they do not match the cherished exclusivity of the Belgian nobility. ‘The Dutch aristocracy has never been extreme or ostentatious’, says Ileen Montijn, author of Hoog geboren: 250 jaar adellijk leven in Nederland (High-born: 250 years of noble life in the Netherlands). ‘After the Second World War a period of “extreme hiding” began. In the 1960s and 1970s, having a noble title was almost excruciating, an inappropriate means of distinction in a democratic society. For those who had a title it was wise not to use it. Even the Royal Household distanced itself from the nobility. But now, after decades of hiding itself, the Dutch aristocracy has regained its self-confidence. Since the 1980s especially, they have got over their shame. Royalism among the nobility remains strong, but in recent decades the relationship has been watered down. There is the surprise that the Royal Household makes so little use of the nobility’s unconditional willingness to serve. This is to some extent out of caution on the part of the Oranges. They don’t want to lay it on too thick in front of the people and like to appear ordinary. None of the princes has been able to find a ‘lady’ or a baroness, they have all been passed over. But then the nobility itself has also long since stopped marrying in its own circle, although it was almost obligatory for centuries. They are both, nobles and princes, children of their time.’

Ileen Montijn: ‘The Dutch aristocracy has never been extreme or ostentatious’

Ileen Montijn: ‘The Dutch aristocracy has never been extreme or ostentatious’Another phenomenon of the time is that the rare nobles who still own a family castle – like their Belgian colleagues – can only maintain it with sacrifice and personal commitment, combined with commercial exploitation (such as receptions, dinners and visits). Although the times have changed and the number of noble mayors, members of parliament, courtiers and ministers has shrunk considerably, there are still relatively many noble families and individuals who play a significant role in the Dutch administration and business life.

Today, Dutch nobility is mainly seen as the last bastion of decency and civility in a society that is becoming coarser. The exceptional image of nobility is in the twilight zone between objective characteristics and perception. Those who believe that aristocrats have noble characters will often find confirmation of that idea and ignore any other cases as exceptions. Dutch Baroness Floor van Dedem sums up this effect with a colourful comparison, ‘If I wear pearls from a drugstore, everyone thinks they are real. If the woman next door were to wear them, they would immediately be fake. That’s how it works.’

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.