Boozers, Militiamen And Mischievous Looking Women: Frans Hals Brought Them All Masterfully To Life

The Rijksmuseum is exhibiting around fifty of Frans Hals’ best works. This selection puts a virtuoso craftsman in the spotlight. The seventeenth-century master could transform smears of paint into striking portraits like no other.

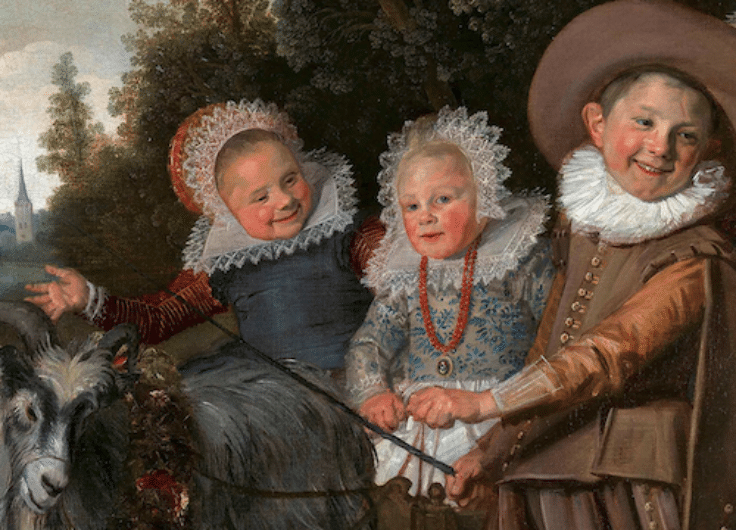

When you walk into the Frans Hals exhibition at the Rijksmuseum, the museum keeps the paintings to itself for a while. His name is lit up in neon letters, and his wild brushstrokes are psychedelically magnified in black and white. What are we going to see here? What are we going to experience? “Raw” the exhibition text says in the first room, and The Merry Drinker waves towards us with a well-filled Berkemeyer teetering on his fingertips, as if to say “grab a glass, come in, I’ll introduce you to my friends”.

A Militiaman Holding a Berkemeyer, known as ‘The Merry Drinker’, c. 1629

A Militiaman Holding a Berkemeyer, known as ‘The Merry Drinker’, c. 1629© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

And then it begins, room after room, portraits and tronies of merchants and children, militiamen and drunkards, sex workers and music makers who seek eye contact with us, shyly smiling, giggling, some displaying their bad teeth as they roar with laughter. After I return their gaze and laugh back at them all, I start my round again, observing more closely.

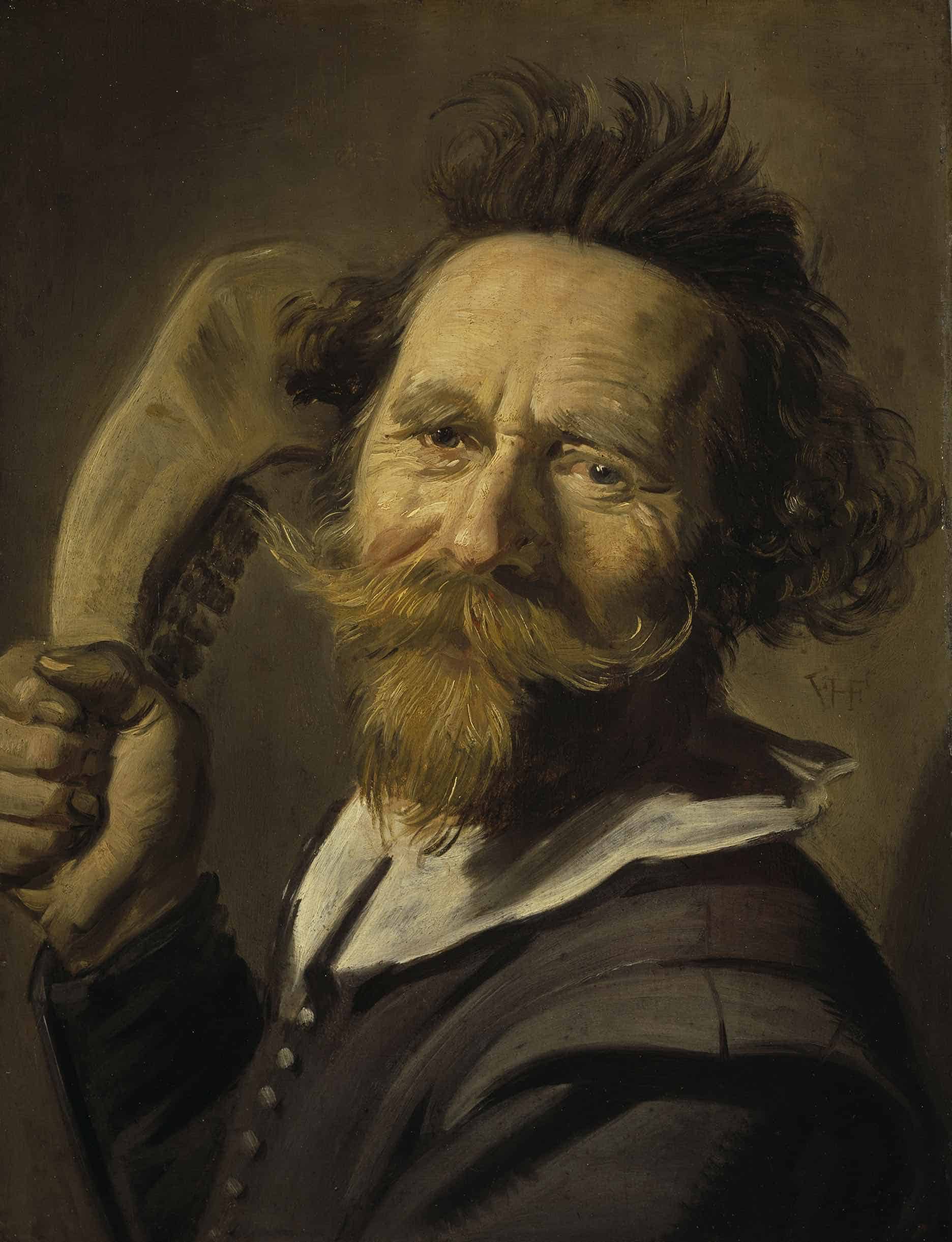

I see the loving look with which a wife looks at her husband, her right hand has been intimately intertwined with his for four centuries. I look into the brown eyes of a man who we think might be called Pieter Verdonck – eyes that hold me in a mixture of glee and despair, and only later do I see the remarkable donkey jawbone he has clutched in his hand. The lute player appears, his hands on the strings of his instrument, all movement, up to his swirling hairs.

Hals’ masterful brushstroke appears everywhere, managing to capture the softness of feathers, the coldness of a skull and the moistness of an eye, with a touch that becomes increasingly turbulent over the years – ferocity in which everything is under control.

Portrait of Pieter (?) Verdonck, c. 1627

Portrait of Pieter (?) Verdonck, c. 1627© National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

48 Paintings

Major Frans Hals exhibitions have taken place in 1937, 1962, and 1990, and now, in 2024, at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. The exhibition began last year in a slightly different form at the National Gallery in London and will soon travel, again in a different guise, to Berlin’s Gemäldegalerie. For the Amsterdam exhibition, 48 paintings were selected by curator Friso Lammertse from the 220 that the Rijksmuseum attributes to the master.

After the first monograph on Hals was published in 1871, a stream of publications followed in which one central question occupied people’s minds – which works were, weren’t, or were partly painted by the master himself? Two major oeuvre catalogues were key moments in this discourse – one by Seymour Slive from 1970-1974 (222 paintings) and the other by Claus Grimm from 1989 (145 paintings). In his latest research, which he conducted in collaboration with the RKD Netherlands Institute for Art History and the Frans Hals Museum, Grimm has counted 120 of the master’s own works. The first part of his new catalogue raisonné has now appeared online on the RKD website, and the full catalogue will be published online later this spring.

The Rijksmuseum still broadly follows Seymour Slive’s attributions and it’s refreshing that this discussion isn’t central to the catalogue that accompanies the exhibition. The reason for this, the authors say, is that material-technical research into Hals’ oeuvre is still in its infancy. Something very different in comparison to the oeuvres of Rembrandt and Vermeer! But what a sense of peace that brings to looking at the paintings! While it is miraculous to look at paintings with X-ray equipment, infrared technology and other digital wonders, it’s even more miraculous to do it with our own eyes – aided by the first-class essays in the catalogue.

Renaissance elbow

Of course, these essays often focus on the master’s astonishing brushwork. Frans Hals (born around 1584) arrived in Haarlem with his parents as a toddler of around two years old. They were some of the many newcomers who had fled the Southern Netherlands after the Fall of Antwerp. In 1610 Hals joined the Guild of Saint Luke in Haarlem and he also served as a musketeer in the St George militia company.

As a member of one of the Chambers of Rhetoric, he built up a large social network in the city, which has now been better mapped out by new research. Hals also continued to maintain contacts with the Southern Netherlands, and in 1616 he visited Antwerp, where it is very likely that he saw the work of “brush virtuosos” Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens, who were working for Rubens at the time.

This rough touch must have appealed to Hals, who over the years allowed himself greater and greater freedom in using it, mastering it to perfection. You see it when you stand close to the paintings (and then, at home, you can look at the enlarged detail in the catalogue) – smears and strokes, slapped-on smudges and folds in the paint, that when you stand back, miraculously transform into a hand, or a boot, or a lace collar.

In his essay, Bart Cornelis also points out another means by which Hals’ subjects manage to capture our attention. The “Renaissance Elbow” is where the subject holds his hand on his side and stands with his elbow turned towards us. Those graceful elbows not only connect power with elegance, they also connect the subject to us as viewers, as they emerge from the canvas, protruding from the frame and claiming their own space within ours.

The elbows themselves have become their own masterpieces, sometimes paint is roughly brushed together, and sometimes they are painted with extraordinary refinement. Just look at the sleeve of The Laughing Cavalier, on which we can see Cupid’s arrow emerging from a heart flower, or the masterfully painted portrait of Jasper Schade, whose haughty look makes it clear to us that we’ll never have as much sartorial style as him.

The Laughing Cavalier, 1624

The Laughing Cavalier, 1624© The Wallace Collection, London

According to Cornelis, another of “the most glorious figures” that Hals ever painted, is the standard bearer who shines on the far left of The Meagre Company. He also has one of these elbows. Van Gogh wrote about the standard bearer in a letter to his brother Theo, claiming “I have rarely seen a more divine figure.” This painting also offers an exercise in viewing – on the left the figures are painted by Hals, and on the right, the figures are by Pieter Codde, who completed the painting.

The Company of Captain Reinier Reael and Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz Blaeuw, known as ‘The Meagre Company’, 1633, (completed by Pieter Codde, 1637)

The Company of Captain Reinier Reael and Lieutenant Cornelis Michielsz Blaeuw, known as ‘The Meagre Company’, 1633, (completed by Pieter Codde, 1637)© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

But who are all of the figures in the painting? Thanks to new research, the catalogue brings many of them into the spotlight by portraying Hals’ social network and studio for us. New research also shows that Hals must have had international fame, as his name appeared on a list of 350 works by Dutch painters, from which the Danish King Christian IV was able to purchase works. The exhibition catalogue also discusses for the first time portrait prints that were made in the style of Hals’ work.

Wrinkled cheeks and bare teeth

We all know that Frans Hals is the artist of laughter, and if we didn’t know it yet, it has now been made very clear to us by the marketing department at the Rijksmuseum. In an infectiously written essay by Friso Lammertse, we read for the first time about the layered nature of all that roaring laughter in Hals’ work. Although laughter has been around forever, it was investigated in every possible way by the philosophers, physicians, writers and artists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Lammertse takes us into this history and begins with Erasmus, “It is improper when people snort when they laugh. Also unseemly is a smile which shows the gap of the mouth with wrinkled cheeks and bare teeth, it is doglike.” Fortunately, children didn’t know anything about Erasmus, and if Hals’ subjects had had a few too many, decorum went out of the window and the master could grab their howling and guffaws with his brush.

The Rommelpot Player, c. 1620

The Rommelpot Player, c. 1620© Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas

Hals not only excelled at portraying the exuberant smile, he also mastered subtlety and modesty, including in women. He brought love and devotion to life in their smiles and mischievous looks. Lammertse’s essay also teaches us to look at Hals’ work better – to look at how he follows the fleetingness of laughter with the pace and looseness of his touch, to see the brushstroke that sets everything in motion, and yet at the same time stops everything, for us, for me, in the present, four centuries later.

The Frans Hals exhibition can be seen in the Rijksmuseum until June 9th and will then travel in a different form to the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. The catalogue with essays by Bart Cornelis, Friso Lammertse, Justine Rinnooy Kan and Jaap van der Veen. Want to read more about Hals? Then see this reading list of Friso Lammertse’s favorites.