Bound For Sugar: Flemish Traders on Madeira

Two Flemish merchants, Maerten Lem and Jean Esmenault, travelled south in the late 15th century. They left an imprint on the history of the Portuguese island of Madeira that is still visible today. Their fascinating story and that of their descendants is all about sugar.

On 1 July 1419, exactly six hundred years ago, two squires to prince Henry the Navigator, first set foot on the island Madeira in the Atlantic and claimed it for Portugal. Settlements rose up in the following decade, but it was only in the 1450s that the landowners got serious about economics. The climate on the rugged, wooded island was suitable for sugarcane and wine, two luxury products for which demand in Europe was high. As the landowners did not have the workforce to chop down the massive woodlands, they set them on fire. The ancient forests are reported to have burned for years. At the same time, levadas were dug: aquaducts carrying water from the north of the island, which is wet, to the south that was fit for agriculture. The landowners still needed to fetch the best price for their products on the continent. And where else to find a dependable merchant with a healthy cash-flow but in Flanders.

Madeira

Madeira© Dalmava

The Leme's

Maerten Lem, a Bruges merchant, arrived in 1450 in Lisbon with a letter of reference from Isabella of Portugal, wife of Philip The Good, both duke of Burgundy and count of Flanders. Maerten Lem made his fortune by exporting cork and sugar. In the sixteen years that he stayed in Lisbon, he fathered at least seven children to Leonor Rodrigues whom he never married. His oldest, Martim, was named “o Moço” (the Younger) and the family name was changed to Leme, which has a better ring to it in Portuguese. The Bruges merchant returned home in 1466 to pursue a career in politics as mayor of Bruges and advisor to Maximillian of Austria.

Huize Ryckenburg on the Bruges Spiegelrei, where Maerten Lem resided on his return from Madeira

Huize Ryckenburg on the Bruges Spiegelrei, where Maerten Lem resided on his return from MadeiraIn 1470, Martim o Moço, a nobleman like his father, settled in Madeira and was part of an export cartel in wine and sugar. In December 1481, his name is mentioned twice in the records of the Funchal municipality: once for a shipment of grain that he failed to deliver, and one for participating in illegal gambling in the Rui de Araujo bar. Six months later, he is fined 250 golden cruzados and his possessions are seized. We assume that the grain was to have been shipped by his father from Bruges. A bad harvest in Flanders had provoked famine in the Low Countries and Maerten must have been unable to export the grain. Still, eleven months later, in May 1483, Martim o Moço’s fine is annulled and his possessions returned, a proof that Martim must have used his father’s excellent connections at the Portuguese court.

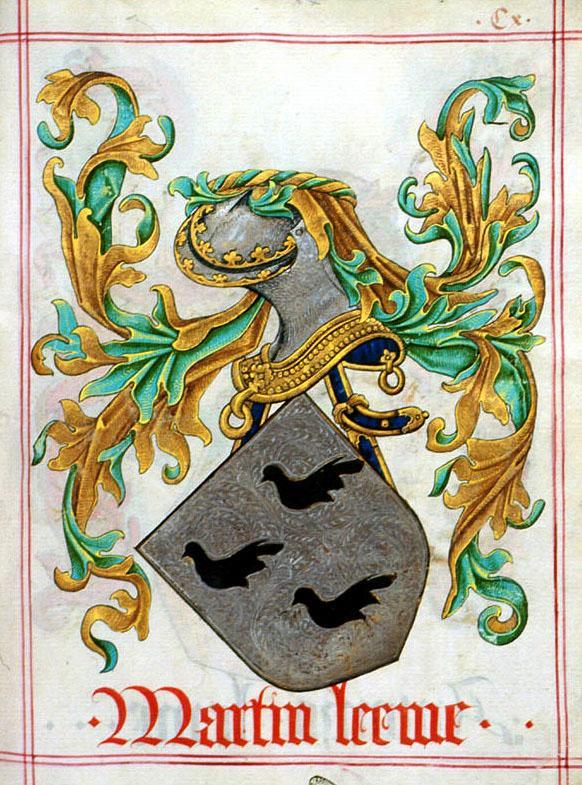

Martim Leme’s coat of arms

Martim Leme’s coat of arms© Wil Lem

Slave labour

Martim’s brother Antonio was a seafaring man and a friend of Christopher Columbus, a frequent visitor on Madeira. Legend has it that Antonio told Columbus about an ill-fated voyage to Africa, when a storm put his ship spectacularly off course. Antonio, adrift on the Atlantic, could distinguish three islands in the West: the very Bahamas where Columbus was to set foot on years later. We may assume that Antonio was not the only one to claim to have tipped the great explorer about the existence of the America’s. Antonio Leme eventually settled on Madeira, marrying a great-granddaughter of Zarco, one of the squires who had claimed the island for Portugal back in 1419. Antonio’s union propelled him into the social elite of Madeira and his manor house Quinta do Leme still exists outside Funchal. By 1494, the Quinta do Leme produced 15 tons of sugar per year using slave labour. It is estimated that, by the closing of the 16th

century, African slaves made up a tenth of Madeira’s population.

Two sons of Antonio Leme enlisted in the Portuguese military, who used the island of Madeira as a strategic vantage point for raids into Islamic Morocco. Two other sons kept busy in the sugar trade. Antonio’s grandson, Antão, emigrated in Brazil, most probably at the behest of wealthy Antwerp trader Erasmus Schetz who had bought a plantation in São Vicente and needed experts on sugar production. We do not know what post Antão held exactly at the so-called Engenho dos Erasmos plantation. Today, it is a classified site of industrial archaeology.

A somewhat romantic depiction of the Portuguese arrival in São Vincente, painting by Benedito Calixto (1853–1927)

A somewhat romantic depiction of the Portuguese arrival in São Vincente, painting by Benedito Calixto (1853–1927)© Museu Paulista

The most famous descendant of Martim O Velho was Fernão Dias Paes Leme (1607-1681) who his contemporaries described as a red-haired giant. He was a so-called bandeirante, an adventurer who led expeditions in search of gemstones into unmapped regions of Brazil. His crew mutinied during one of his arduous journeys. He hung all the mutineers, including his own mulatto son. Fernão has been remembered on a stamp and a banknote in Brazil. The thoroughfare between São Paulo and Belo Horizonte was named after him.

The Esmeraldo's

Fernão Dias Paes Leme’s statue - the Bandeirante - at the Paulista Museum in São Paulo

Fernão Dias Paes Leme’s statue - the Bandeirante - at the Paulista Museum in São PauloBethune-born Jean Esmenault, employed by the Bruges trading family Despars, arrived in Madeira in 1480. He oversaw shipments of sugar to Bruges and, in 1490, when the Despars quit their ventures in Portugal, he decided to stay and set up shop himself. He changed his name to João Esmeraldo and married a granddaughter of the aforementioned squire Zarco. When his wife’s uncle left for the Azores, João bought his sugar plantation in Ponta do Sol. Thus, he became the owner of the largest plantation in Madeira, producing 300 tons a year.

João had two sons who each inherited half of his property. The most dynamic of them was Cristòvão whom his father had named after Christopher Columbus. Cristòvão made a name for himself in the war against Morocco. He was a ruthless schemer and compelled his underage son Antònio to marry his brother’s daughter Antònia so that his son could take possession of the entirety of his grandfather’s lands. The marriage between the underage nephew and niece took place in Lisbon in 1539 and needed a special authorisation from the pope. The Portuguese king however felt aggrieved as his consent for the marriage had not been solicited. He sequestered the bride and charged Cristòvão with a 200 cruzados fine and a two-year banishment to Africa. Yet the resourceful Cristòvão obtained a papal bull, addressed to the archbishop of Funchal, allowing him to claim the bride wherever she was held. Such was the might of the Esmeraldo’s in the kingdom of Portugal in the 16th century. The marriage that caused so much uproar ended in a minor key as illnesses claimed both young spouses by their eighteenth birthday.

Lombada dos Esmeraldos, the estate of João Esmeraldo and his descendants

Lombada dos Esmeraldos, the estate of João Esmeraldo and his descendantsLasting imprint

In the ensuing decades and centuries, the wealth of the Esmeraldo family grew as did the length of their family name. In the late nineteenth century, it was Antònio Leandro da Câmara de Carvalhal Esmeraldo Atouguia Betencourt Sá Machado who squandered the accumulated family fortune by throwing splendid feasts is Paris, Madrid and Lisbon. He ended up destitute in his Madeira castle, where his properties were seized and sold off. He died without a real

to his name in 1888, aged 56. He is portrayed, in happier days, on a mediocre painting depicting a picnic in the Quinta do Palheiro gardens on Madeira.

Tomás da Anunciação, The family of the 2nd Earl of Carvalhal on a picnic at Quinta do Palheiro Ferreiro, 1865

Tomás da Anunciação, The family of the 2nd Earl of Carvalhal on a picnic at Quinta do Palheiro Ferreiro, 1865© Wikipedia

There have been more Flemish tradesmen who came to Madeira on business but only Maerten Lem and Jean Esmenault managed to make a lasting imprint. The descendants of Lem have scattered all over the globe. Those of Esmenault were less numerous but still live in Madeira.