Brent Annable’s Choice: Annie M.G. Schmidt and Thea Beckman

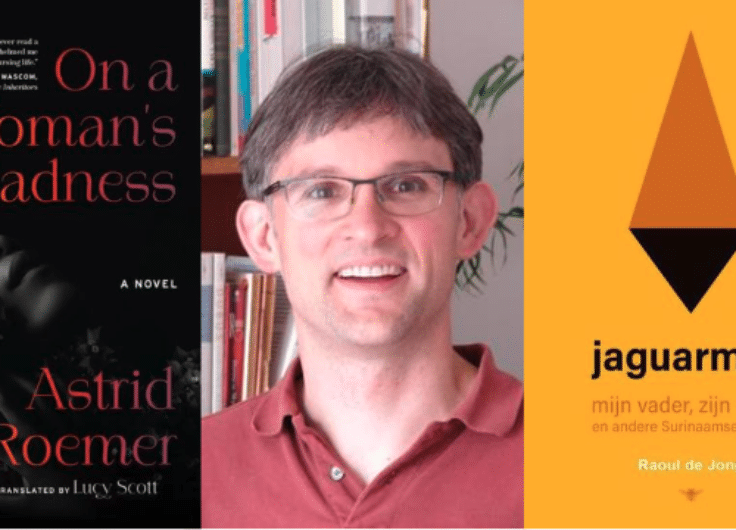

Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. Australian translator Brent Annable makes an ardent plea for the sparkling sentences of two grandes dames of Dutch children’s and youth literature.

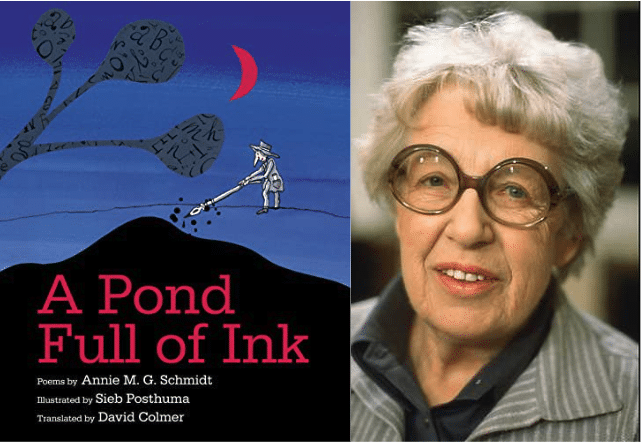

Must-Read: ‘A Pond Full of Ink’ by Annie M.G. Schmidt

Annie M.G. Schmidt is one of the undisputed leading lights of Dutch children’s literature. Her works cover a multitude of genres, including songs, books, plays, musicals, and even radio and television drama for adults. But as a lover of rhyming poetry, my favourite works of hers are her children’s poems, which never fail to capture my imagination and bring a smile to my face.

A few years ago, I was overjoyed to discover A Pond Full of Ink, an illustrated collection of Schmidt’s most beloved poems in an English translation by David Colmer. All the great classics are there: Sebastian Spider, who could not control his urge to spin a web indoors; The Fairy Failure, about a fairy with unacceptably freckly skin; Nice and Naughty, a childhood lament to good manners; and Little Princess Annabel, whose ‘prickly’ personality gets her turned into a hedgehog. The translations, too, are marvellous, preserving the poems’ original humour, rhyme and meter, but without ever becoming too contrived or overwrought. Some of the rhymes are especially ingenious: the poor freckled fairy, ‘though just as graceful… had a face full’, and of bath-hating Belinda it is said that ‘The more she avoided a bathroom or scrubbery / The more she began to resemble some shrubbery.’

I have attempted verse translation on occasion, with varying degrees of success. It’s hard work. The trick is to make it not sound like hard work, and that is where Colmer’s translation really shines. The lines read as effortlessly and naturally as they do in Schmidt’s originals, giving non-Dutch speakers a rare opportunity to experience these children’s classics as they were meant to be enjoyed.

Annie M.G. Schmidt, A Pond Full of Ink, illustrated by Siebe Posthuma, translated by David Colmer, Eerdmans, 2014, 34 pages

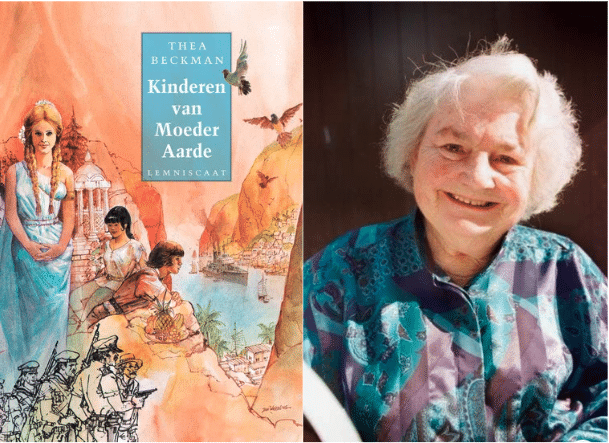

To be translated: ‘Kinderen van moeder aarde’ by Thea Beckman

Another – arguably the other – towering figure of Dutch children’s literature is Thea Beckman. The first book I ever read in Dutch was her young-adult fantasy epic Kinderen van moeder aarde (Children of Mother Earth), a post-apocalyptic adventure set in Greenland a thousand years in the future, where a utopian and exclusively matriarchal society flourishes based on principles of non-violence and care for the planet. When European explorers arrive in an armed battleship intending to plunder its natural resources, conflicts and misunderstanding inevitably ensue.

Kinderen van moeder aarde

deserves a modern translation in English for many reasons. It contains powerful messages on feminism, gender roles, war, family conflict, and the environment – all themes that are as relevant today as they were nearly forty years ago when the book was first published. Beckman’s sophisticated style is also a joy to read, drawing the reader in with elegant yet compelling formulations. All that aside, it’s also a ripper of a story – I still have trouble putting it down, even after having read it many times.

The excerpt I’ve chosen exemplifies Beckman’s typically forthright, unapologetic style. It is our first introduction to why post-war society in Greenland (Thule) is strictly matriarchal, from the perspective of the ruling monarch’s only son, Christian.

Thea Beckman, Kinderen van moeder aarde, Lemniscaat, 1985, 495 pages

Excerpt from ‘Kinderen van moeder aarde’, translated by Brent Annable

Kimora, the palace tutor, had given Christian a general education, had taught him how the country was governed and that things were good the way they were: with the males in the population subordinate to the females.

Kimora had told him that once, unthinkably long ago, things had been different, that despite their superior talents, sensitivity and importance, women had held no power. Men had ruled the world, and done a poor job of it. Century after century, injustice, cruelty and self-interest prevailed; century after century there flowed rivers of blood, people hated one another and could barely conceive of enough ways to cause themselves injury. Those had been dark times, and their conclusion was inevitable: things went horribly wrong. Society crumbled until nothing remained but countless dead, unimaginable destruction and only a handful of desperate survivors. Mother Earth, furious at the injustice that had been wrought unchecked upon Her skin for millennia, had exterminated the human race. And from the wreckage arose a new people: the Thuleans, who had learned to listen to Mother Earth’s words of wisdom. The Thuleans understood that women were the most important beings on Earth. Women created new life, women showed mercy, they were sensitive, honest and intelligent. They were prepared to take the wishes and needs of others into consideration. They were also better equipped in the general struggle for survival, as they were more versatile, resourceful and resilient, and bore up more strongly than men in times of pain or sadness.

And they had a very strong grasp of that which most men did not: intuition. Having a crystal-clear sense of what needed to be done, and then getting on with it without a needlessly inflated notion of self-importance, and without first thinking: but what’s in it for me? To women, general well-being, children and health were top priority. With women, people were safe: women took good care of you. It was for this reason that never, not in a thousand eternities, would a man ever be allowed to sit on the throne of Thule. Men were nice, strong and often friendly beings suitable for heavy labour; they could till the soil, cut down trees, lift heavy cargo and build houses, but they were not to be trusted with matters as sensitive as national governance. For that they were simply too rough, too headstrong, too self-serving…