Bruegel, Painter of Riddles and the Magic Mundane

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the painter of the simplicity and humour of farm life. This is how we perceive the most significant Renaissance painter of both Flanders and the Netherlands. But is that image correct? Flemish author Jeroen Olyslaegers unravels the mystery of the magic mundane of this Flemish master.

I am just a young boy – about ten years old, give or take. My father is an artist, and the shelves of his library are crammed with books on art. I ask him whether I am allowed to leaf through that one big book again. It is quite tricky to try and piece together memories. However, I am pretty sure that, while looking over all those paintings and pictures, I experienced a feeling of familiarity. Even at that tender age I was already caught up in the phenomenon that has been plaguing Bruegel scholars for ages: his oeuvre is one that is both elusive and recognisable – that unusual combination could cause someone to feel like an insider, like someone who truly understands what his work is about.

‘Nature has discovered her Man in the best possible way, only to be captured by him in turn in the most delightful way, for in an unknown Brabant Village among Peasants she has chosen the very witty and funny Pieter Bruegel to become a masterful painter, and to recreate Peasants by way of a Paintbrush, bestowing fame on us, the Dutch (…)’

Jeroen Olyslaegers in Museum Mayer van den Bergh

Jeroen Olyslaegers in Museum Mayer van den Bergh© Sigrid Spinnox

And so begins the very first description we have in writing of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. These words can be found in Flemish writer and painter Karel van Mander’s Schilderboeck (Book of Painters), published in 1604, some thirty-five years after Bruegel’s death. Quite possibly, the way we currently look upon this enigmatic painter is still influenced by the complete biographical sketch this fragment was taken from.

A once in a lifetime find

Bruegel and Bruegel scholarship should be categorised as a twentieth-century phenomenon. Although he was highly regarded for a number of generations after his death, hardly anyone appreciated Bruegel’s work during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He was quickly forgotten about, so much so that art dealers and collectors would hardly differentiate between his work and that of his sons, i.e. Pieter Bruegel the Younger (who was nicknamed ‘Hell Bruegel’) and Jan Bruegel (nicknamed ‘Velvet Bruegel’).

Can you imagine the absolute shock Fritz Mayer must have experienced when the painting finally arrived in Antwerp, and was unwrapped in front of his eyes?

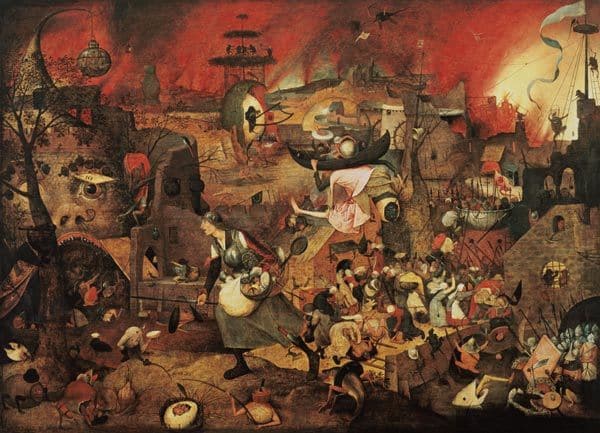

One of the stories that illustrates Bruegel’s diminishing popularity quite wonderfully is the one about the purchase of the infamous masterpiece entitled Dulle Griet’ (anglicised as Dull Gret, also known as Mad Meg). In fall of 1894, the – at the time still youthful – art historian Max Friedländer reached out to German Antwerp-based art collector Fritz Mayer van den Bergh. Friedländer informed him that auction house Heberle in Cologne had a piece of art on offer he might find interesting.

The painting, labelled number 48 in the catalogue, was described as a “fantastical depiction of a landscape featuring many ghostly images”. The catalogue also mentioned the work may have been painted by one of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s sons. For the time being, the painting was hung high on a wall. Friedländer needed to climb a ladder to be able to inspect it up close. Saying Fritz Mayer was intrigued by the art historian’s enthusiastic advice would be an understatement. He instructed his agent to purchase this curious painting on 5 October 1894, for 488 old Belgian francs, a modest sum of money in a time when you could easily spend many thousands of francs on a painting by Rubens.

Fritz Mayer van den Bergh by Jozef Janssens de Varebeke

Fritz Mayer van den Bergh by Jozef Janssens de Varebeke© Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

Can you imagine the absolute shock Fritz Mayer must have experienced when the painting finally arrived in Antwerp, and was unwrapped in front of his eyes? All of a sudden he was faced with a panel that was not painted by Pieter Bruegel the Younger, but instead by his father, the acclaimed and ever-mysterious Pieter Bruegel the Elder. After all, the art collector knew his stuff. In his Book of Painters Van Mander mentions a painting that – at the time – was owned by Rudolf II in Prague. Van Mander describes it as “a ‘dulle Griet’ (‘Mad Meg’) who goes on a rampage in Hell, and looks amazed and is dressed in een odd Scottish manner.”

As it turned out, Fritz Mayer van den Bergh made the purchase of a lifetime.

This story could be classified as part of the origins of Bruegel scholarship. It is interesting to note that Van Mander’s words allowed one of the most important paintings by Bruegel to be identified almost three centuries after they were written down.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Mad Meg, 1563© Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp

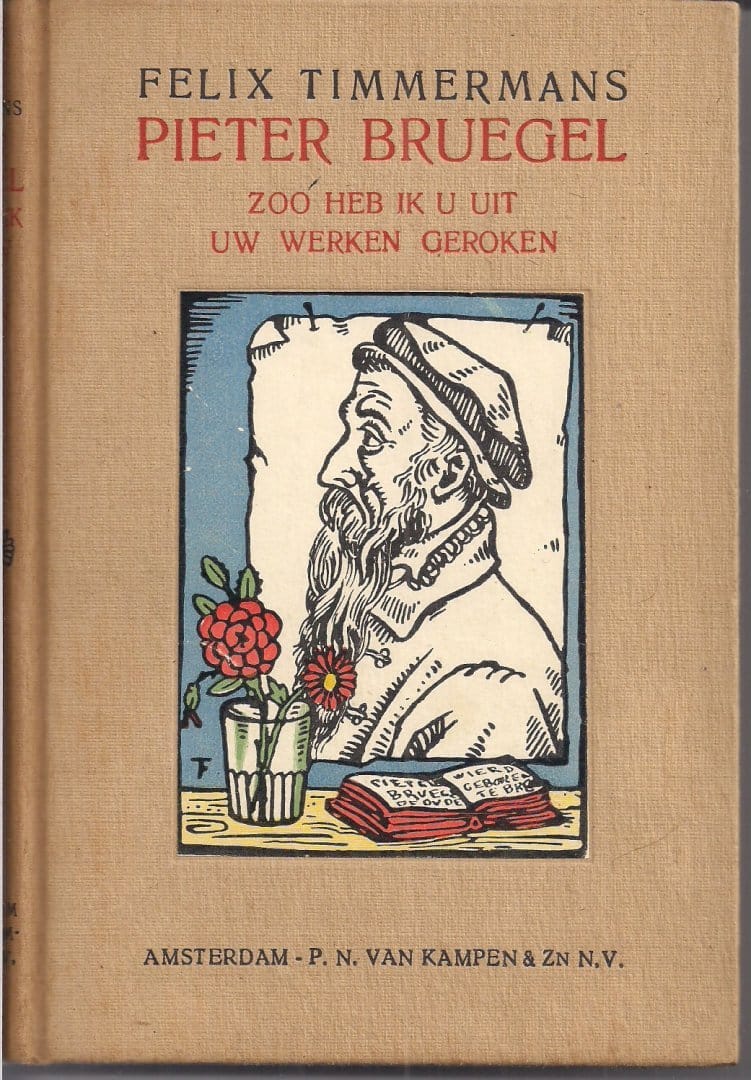

‘Our’ Bruegel

During the first half of the twentieth century, numerous studies on Bruegel follow in quick succession. Suddenly, Bruegel becomes a source of inspiration for bƒoth art historians and authors of literary fiction. Flemish author Felix Timmermans – who was well loved at the time – caught the Bruegel bug in the 1920s. Back in 1928, he published Pieter Bruegel – zo heb ik u uit uw werken geroken (Pieter Bruegel – thus I have smelled you in your work), a true gem of a title, which to this day both moves and amuses me. In this story, it is clear Timmermans holds the painter close to his own writer’s heart, as he takes him with him in his world, characterised by simplicity and the sense of humour that is so typical of peasant life. That should not come as a surprise, as Karel van Mander acts as a guide here as well. He discusses Bruegel’s fascination with peasant life. Van Mander describes how, joined by his close friend Hans Franckert, the painter attends peasant weddings in hopes of getting inspired:

‘With this Franckert by his side, Bruegel would often go outside to join the Peasants, at their Fairs, and at their Weddings, dressed up as a Peasant, giving gifts like the other guests, pretending to belong to the bride’s or the groom’s family or people. Bruegel rejoiced in doing so, being among the Peasants, eating, drinking, dancing, jumping, making love, and seeing other humorous things (…)’

Obviously, we are no longer able to check the sources Van Mander consulted, but it should be noted that this anecdote is filled with double entendres. It seems Bruegel and Franckert entered the scene in disguise, as if they were two peeping toms, hoping to later recreate peasant life to the best of their abilities on canvas and wooden panels.

Clearly, this is an irresistible story, which in 1928 Timmermans infuses with a love for the common folk. Tales like these resulted in the so-called ‘Boeren-Bruegel’ (Peasant Bruegel) persona, who in turn becomes part of a larger narrative on national identity over the ensuing centuries. Bruegel thus becomes ‘ours’, i.e. belonging to the people of Flanders. This myth comprises every single element that would appeal to literate supporters of the Flemish Movement. On the one hand, we have the difficult relationship with the agricultural profession: farmers are being glorified because of their simplicity and sincerity, yet they are always kept at a distance. On the other hand, humour plays an important strategic role, allowing Bruegel to become someone who is constantly hedging his bets; thanks to his disguise he remains true to his sense of irony, whereas he can simultaneously profess his love for the people.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, 1567-1568

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Peasant Wedding, 1567-1568Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

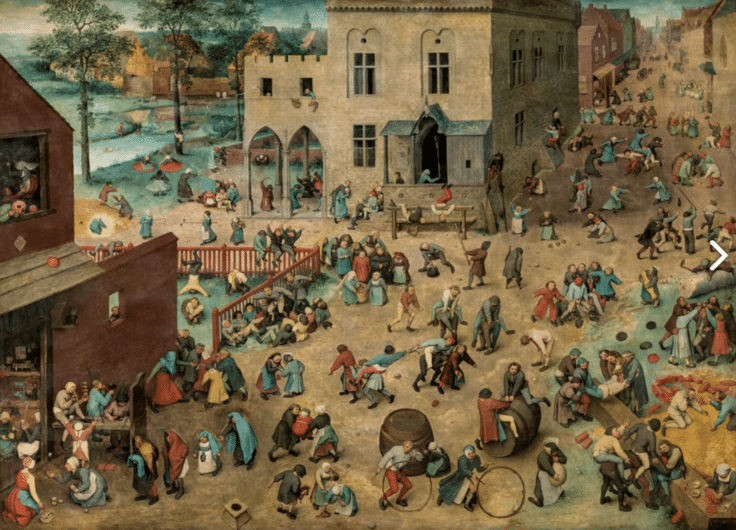

Land of Cockaigne

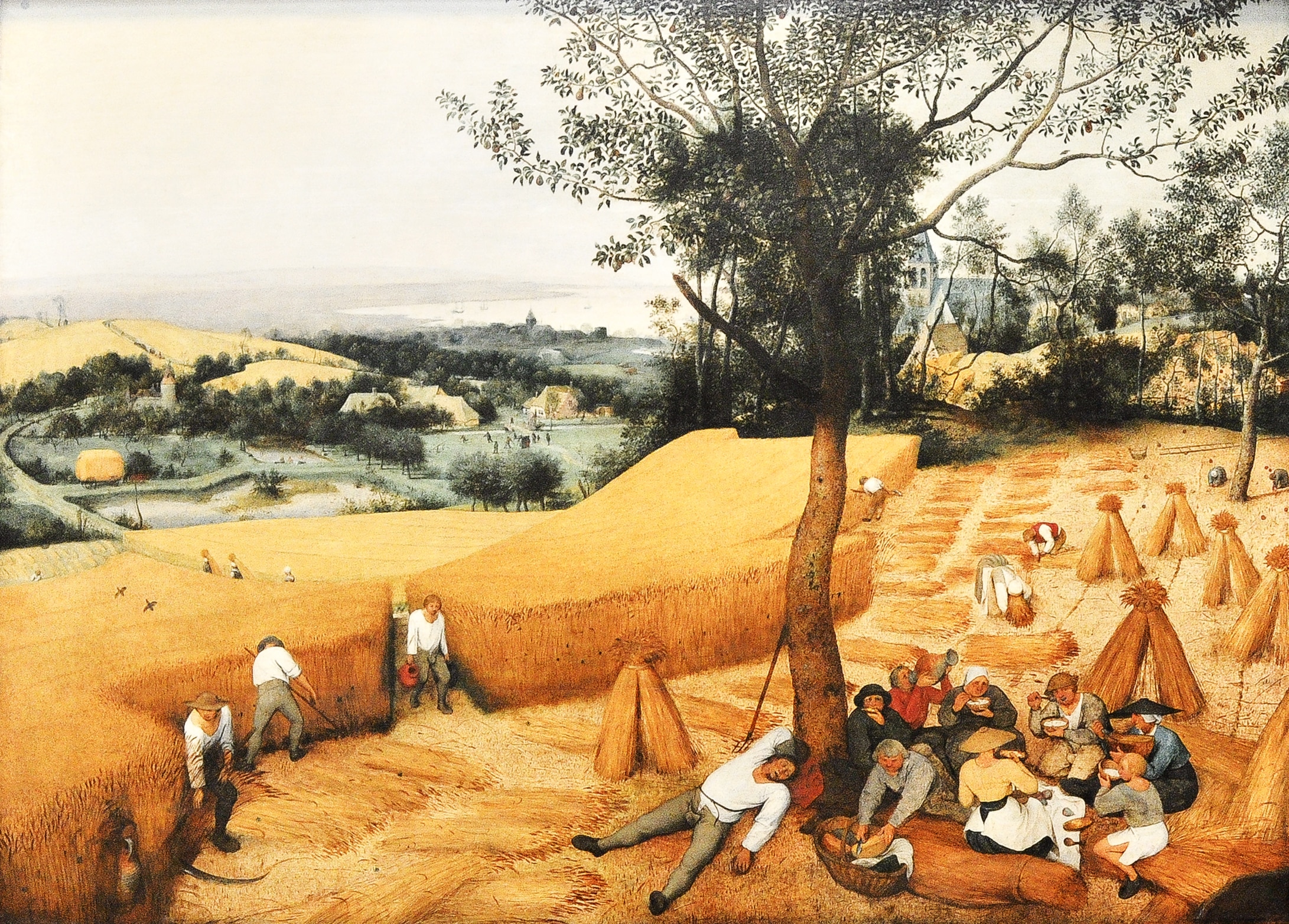

We could ask ourselves whether this distant glorification of farming life was actually present in Bruegel’s time. His clients would have been city dwellers. They would not have been of noble birth, but would make a living through trade, which was growing steadily in importance. One of them was Antwerp-based merchant banker and art collector Nicolaas Jonghelinck (1517-1570). We know Jonghelinck owned over a dozen of Bruegel’s works, and commissioned De oogst (The harvest) from the painter in 1565.

A bountiful harvest was rare at that time. Because of weather conditions – which have know come to be known as the ‘Little Ice Age’ (LIA) –, winters tended to be bitterly cold, causing the Scheldt to freeze over, and summers tended to be wet. Back then, a city like Antwerp depended on the import of rye from to Baltic in order to be able to feed its inhabitants. If the Scheldt froze over, the city would be struck by famine, leading to civil unrest. What Bruegel shows us is actually a fantasy, an imaginary place called ‘land of Cockaigne’, so beautifully described by Dutch historian Herman Pleij in one of his books (Dromen van Cocagne. Middeleeuwse fantasieën over het volmaakte leven / Dreaming of Cockaigne. Medieval Fantasies of the Perfect Life (1997)).

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Dance, ca. 1568

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Dance, ca. 1568Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

I am stating the obvious here by saying the Flemish Movement never truly accepted urban culture, never mind reflected on it, or even understood it. It should not come as a surprise that country life and the farming profession was idealised back in the sixteenth century by people who made a living through trade – some of whom were not above speculating on the price of grain while famine was raging.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvest, 1565

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvest, 1565© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The ‘Peasant-Bruegel’ myth, similar to any idyllic tale, is a stubborn one. Therefore, the purely scientific work by Manfred Sellink, or studies by representatives of younger generations of scholars (including Tine Meganck) are gaining importance in Belgium. They actually demonstrate that the field is wide open, and there is still so much left to discover. In my opinion, thanks to the recent research on materials and techniques, the exquisite monographic Bruegel exhibition in Vienna (October 2018 – January 2019) has definitively put the image of ‘Peasant-Bruegel’ to bed. In that exhibition we were confronted with one of the greatest in the art world, who somehow remains an enigma, and somewhat of an unsolved riddle.

Now we know for sure that every brush stroke was his, it is difficult not to consider Pieter Bruegel an ‘autonomous’ artist. He would work alone, without the help of assistants, which was rare in his day and age. It is tempting to look at him in isolation, ignoring his historical surroundings and the various circumstances in which he had to sell his work. But what do we really know about his relationship with his different clients? Those exchanges must have had some substance to them, mustn’t they? The truth is we have not got a clue. If we then turn to two studies carried out by Tine Meganck, i.e. the detailed research of De val der opstandige engelen (The Fall of the Rebel Angels), or her study of the surroundings of Abraham Ortelius, one of Bruegel’s closest friends – the Bruegel’s world becomes increasingly intricate. Thanks to Meganck, the interactions between Bruegel and his contemporaries have been exposed.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562© Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

The key to magic

Bruegel keeps us all on our toes. After all, a painter who is able to convince a ten-year-old child it has understood him, and once again becomes a mystery as soon as that same child has grown into adulthood is capable of that. Bruegel has taught us to see, in a way. He ‘directs our gaze’ as Manfred Sellink once put it, and we can but agree. Often Bruegel shows us that spectacular events, such as Christ’s Way of the Cross, or Saul being flung off of his horse because of a divine vision, are actually quite insignificant, and are often accompanied by indifference, distance or a lack of attention. He paints those events amidst a sea of people, with each of the bystanders completely absorbed by their own inner turmoil.

Dulle Griet (Mad Meg), for instance, does not allow you to avert your gaze; you keep wondering whether she is actually there in spirit surrounded by Bruegel’s rendition of the apocalyptic chaos. I believe thàt is where the key to understanding the magical power he has over his audience lies. He is at once one of us and manipulating, simultaneously recognisable and enigmatic. ‘Keep on looking’, his paintings seem to whisper, ‘and dare to get lost in your own thoughts.’

Van Mander just might have captured the master perfectly in 1604, when he described him as an artist in disguise who becomes part of the scenery, an actor who paints riddles that at first glance seem so lifelike. By the way, that would imply we are able to look at that disguise for all eternity: Bruegel, an enigma among us, a masque announced ahead of time.