Brusselisation, Both an Urban Phenomenon and a Historical Milestone

During the second half of the 20th century, Brussels dramatically changed its building stock, a traumatising experience for a large proportion of its population. This transformation was given a name, which, by now, has entered the international literature as synonymous with a lack of willingness or the inability to properly manage urban renovation: brusselisation.

Brusselisation basically encompasses three different dimensions: historical, socio-political and urban. More than anything, it is a denunciation of the post-war transformation of Brussels. It also symbolises a major turning point in the understanding of urban issues and urban governance in Belgium. And finally, it reflects a certain method of urban production in a country that is noted for its traditional hands-off approach on the part of the authorities in the actual construction process of the city by restricting itself to paving the way for private sector development, the process of incentives and the construction of the basic infrastructure.

Brusselisation as a fact

At the end of WWII, the historical city of Brussels was churned over into a large building site. The North-South junction, the railway line, including a tunnel, which connected the North and South Stations, was intended to both join and electrify the Belgian railway network which was recentred on the capital. This project, initiated during the interbellum years, constituted the keystone of a vast economic regeneration programme involving investment in infrastructure works.

The construction of the modern city by private developers. Progressive transformation of the Robert Schuman roundabout by replacing private hotels.

The construction of the modern city by private developers. Progressive transformation of the Robert Schuman roundabout by replacing private hotels.When the tunnel was finally commissioned in 1952, it hailed the start of a new campaign of major works, those of urban motorways. Times had changed. The country aimed to develop private mobility, and this was combined with a housing policy based on promoting small-scale land ownership, and consequently far away from the city centres. The Belgian economy needed to be regenerated with the creation of vast industrial estates along the new motorways. This programme centred around Brussels, and the city was reinventing itself as an international tertiary capital, designed to accommodate the headquarters of new companies spread around the country. The city projected itself literally, symbolically and physically as the ‘crossroads of the West’. Intensive diplomatic activity propelled the city to the position of European and (1958) Atlantic Alliance (1967) capital.

In 1958, the world exhibition was held on the Heysel plateau. This event further accelerated the transformation of the main highways into urban motorways, which connected both nationally and internationally to the new network of European motorways which had been outlined at the Conference of Vienna in 1950. The majority of the network had been designed by the Belgian government’s highway engineers employed by the Ministry for Public Works who had just returned from a training course in the United States as part of the Marshall plan. The architecture of the main roads of Brussels, which until then had been lined with private hotels, was also transformed with the extensive construction of office buildings. New urban players came onto the scene: building developers with close connections to the big construction companies and a financial sector in full growth. Some specialised in the production of housing. The 1960s and 1970s were glorious years for operators such as Etrimo and Amelinkx, who were going to play a major role in the construction of the green residential suburbs of Brussels.

The North district (including the two WTC towers) viewed from the windows of the Centre de communication Nord, early 1980.

The North district (including the two WTC towers) viewed from the windows of the Centre de communication Nord, early 1980.© Bruciel.brussels

These changes all took place without any real overall plan. The planning of the urban motorways was entirely in the hands of the Highways Authority. The latter had all the necessary resources and was able to pursue its own programme. The town planning legislation had provided State control over the urban transformation through local development plans, which actually seemed to have been perfectly made to measure to secure, both legally and in the long term, architectural projects requiring major expropriation. As was the case of the high-rise buildings of the Place de Brouckère and the North district, which is still the most cited example to illustrate the effects of brusselisation.

Brusselisation as a turning point

Until the early 1960s, there were virtually no complaints about the situation. The world of politics, trade unions, employers and the Brussels middle class were all happily migrating to the pleasant suburban countryside. Cement mixers were constantly churning out work, social stability, and ensured an improved standard of living and housing. The metropolisation of the Belgian capital, marked by a concentration of tertiary employment in its centre and housing dispersed over the entire area, seemed to have been the ideal trigger for the virtuous circle of growth and happiness.

Aerial view of the Boulevard Baudouin - Jardin Botanique junction in 1980. This photo in itself provides an excellent illustration of several aspects of brusselisation.

Aerial view of the Boulevard Baudouin - Jardin Botanique junction in 1980. This photo in itself provides an excellent illustration of several aspects of brusselisation.© Bruciel.brussels

However, the tertiarisation of the Brussels economy finally provoked trade union opposition stoked up by the disappearance of industry and the countless demolition works in the popular old districts of the city centre. The residential areas were also hit by the construction of a whole range of apartment and office blocks and local residents were making their feelings felt through associations, such as the Belgian Aesthetics League [La Ligue esthétique belge], objecting to the disappearance of the historical and landscape heritage which until then had been preserved from urbanisation.

In 1968, the upsurge in student discontent mobilised a group of young teachers of architecture of the École nationale supérieure de La Cambre and of the École supérieure Sint-Lukas. In concert with their students, they came to the support of local committees that were springing up everywhere where the city was being renovated. These committees soon joined up with Inter-Environnement and the Brussels Council for the Local Environment (Brusselse Raad voor het Leefmilieu – Conseil bruxellois de l’environnement), which were intellectually driven by such organisations as the Workshop for Research and Urban Action (Atelier de recherche et d’action urbaine) and the Modern Architecture Archives (Archives d’architecture moderne). On the ground, the students were setting up ‘counter-projects’, alternatives to the countless operations in progress, and proposing a return to the city of old, a return to the street as a space for living, to historicist architecture. The gospel of modernity was suddenly confronted with objections against the alienation of the daily commute, the crushing hold of capitalism on the city, the undeniable collusion between the world of real estate and the financial interests of the political parties, the total lack of transparency in public governance, the transformation of a city not for the benefit of its residents but for the economy of the country as a whole. In a nutshell, all those evils were classed under the neologism coined at that time: brusselisation.

All those evils were classed under the neologism coined at that time: brusselisation

These cultural and architectural protests went hand in hand with the conjunction of two socio-political factors. In 1962, the Town Planning Act was voted in, and for the first time it was the State that was in charge of the systematic planning of the country, divided into sectors, including that of Brussels. Plans were only drawn up at the end of the 1960s when another process was started up, that of the federalisation of Belgium. The argument of brusselisation was put forward to demand total control over the town planning of the capital.

As from 1968, the sector-based plan triggered the emancipation of the regional government. From 1973, the responsibility for drawing up the plan was put into the hands of a specially appointed Minister for Brussels Affairs. In 1979, the plan was voted in with a strong defence for the existing city and the creation of new legislation that would make it compulsory for each application for planning permission to be made public and setting up consultation committees that would allow the content of the applications to be debated. These provisions then formed the basis for voluntarist policies for urban renovation which the Brussels-Capital Region then put into place when it was founded in 1989.

Brusselisation is therefore the backdrop and the catalyst of a Brussels movement of political emancipation that has made transparency in urban development and resident participation the founding principles of its institutional identity.

Brusselisation as a reflection of a city design method

One particular provision of the Town Planning Act of 1962 addressed numerous criticisms related to brusselisation: the building development powers granted to the private sector to act on behalf of the public authorities in expropriating owners in the public interest for the strict purpose of implementing development plans, plans that were often designed and tailor-made for development operations.

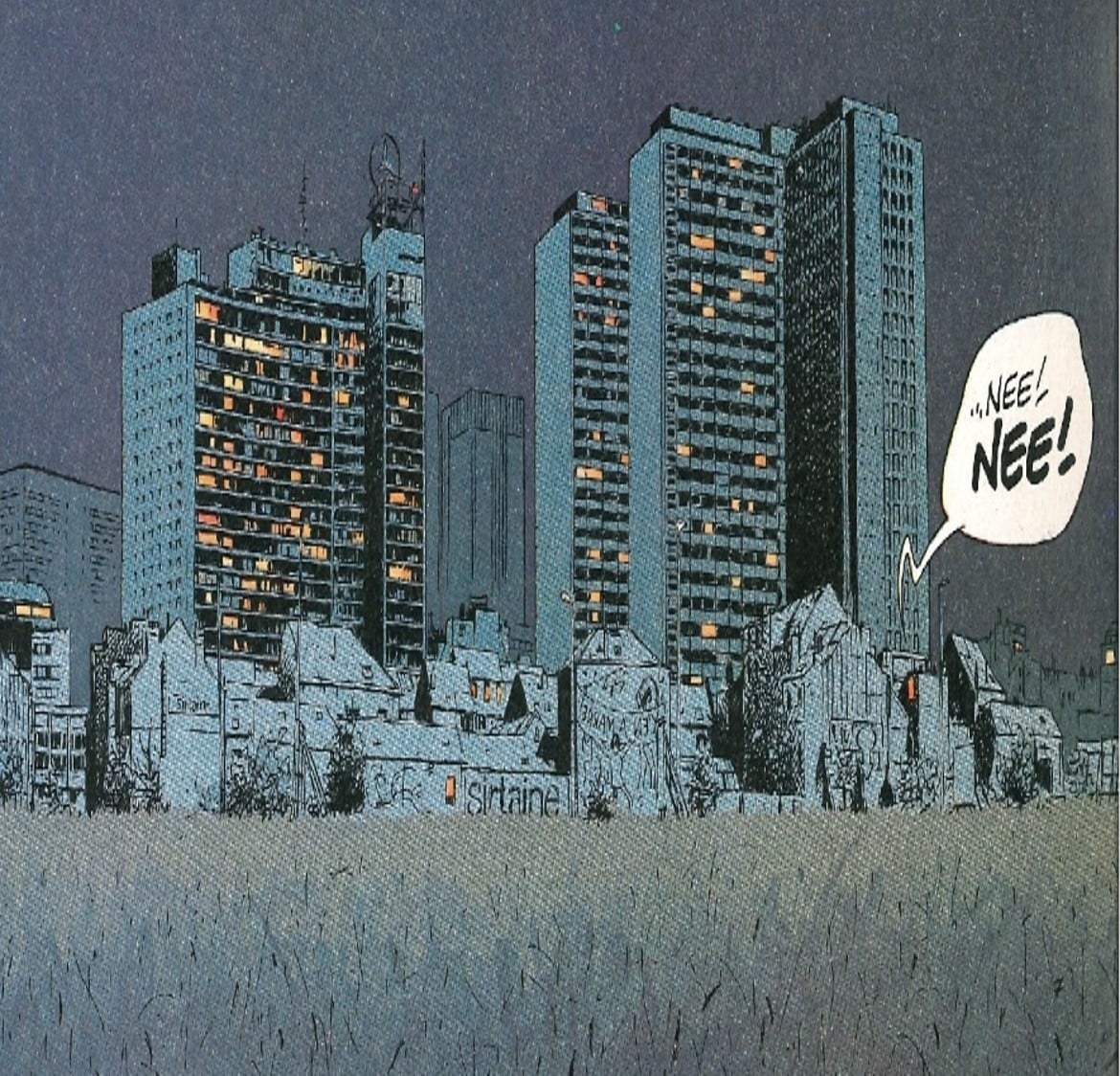

The nightmare of the North district in ruins. Start of the 6th volume of the comic strip series Pharaon by André-Paul Duchâteau and Daniel Hulet released in 1985.

The nightmare of the North district in ruins. Start of the 6th volume of the comic strip series Pharaon by André-Paul Duchâteau and Daniel Hulet released in 1985.This provision, in fact, revealed a typical characteristic of Belgian land management, where the authorities had never taken on the task of actively creating the city. Similar to economic development and education, the State had historically acted by delegation, restricting itself to putting in place the basic infrastructure, such as the motorways, and providing tax incentives, such as bonuses to buy small private properties. Against this backdrop, town planning was mainly exercised through legislation to object to planning applications, and not through any proactive policy.

The transformation and modernisation of Brussels, generally welcomed in the post-war period, therefore had to be based on collaboration with the private sector. They quickly became entwined with market logic, which explains the general hands-off attitude of the authorities in relation to the phenomenal development of offices, which then dominated the economy, the lack of control over the pace of their construction, which finally led to the collapse of the market at the end of the 1970s, and the lack of transparency in the negotiations, marked by a strong collusion between politicians and investors, which was vital to achieve the land profits through speculation.

Construction of the AG Assurances offices, rue de Laeken, on the site of a former high-rise building constructed by the same owner. One of the most emblematic creations of the ‘Brussels Reconstruction’ in objection to brusselisation.

Construction of the AG Assurances offices, rue de Laeken, on the site of a former high-rise building constructed by the same owner. One of the most emblematic creations of the ‘Brussels Reconstruction’ in objection to brusselisation.The condemnation of brusselisation has given rise to a profound reform of the planning and management systems of the urban fabric. Since it was first created, the Brussels Region has instigated a major policy of participative and integrated urban renovation, through ‘district contracts’, which have been applauded internationally, and for quite a number of years it has been pursuing a profound metamorphosis of the canal area with a few striking projects, such as the renovation of the Tour and Taxis site, the transformation of a car showroom and workshops into a modern and contemporary art centre (the KANAL museum which is due to open in 2024) and the renovation of the North district. The legislative framework has also been completely redesigned with the adoption in 2004 of the Brussels Land Management Code [Code bruxellois de l’aménagement du territoire (CoBAT), which has erased the very liberal provisions of the legislation that preceded it for four decades.

Nevertheless, even if the term of brusselisation is associated with Brussels, it is a wider illustration of a method for creating a city that is typical for the whole of Belgium, founded on very limited interventionism on the part of the public authorities on the urban space. It is a method that, even if governance has vastly improved since with public bodies such as the Regional Chief Architect, is still relevant today and explains the difficulties, in Belgium and in Brussels, to really control city development.