C-mine Expedition Keeps Limburg Mining History Alive

If you approach the city of Genk in Belgian Limburg, you will see slag heaps looming in the landscape. They refer to the mining past that is so strongly linked to the identity of this part of the province. At the creative hub C-mine, built on a former mining site, they bring that past to life in an attractive way with the interactive C-mine Expedition.

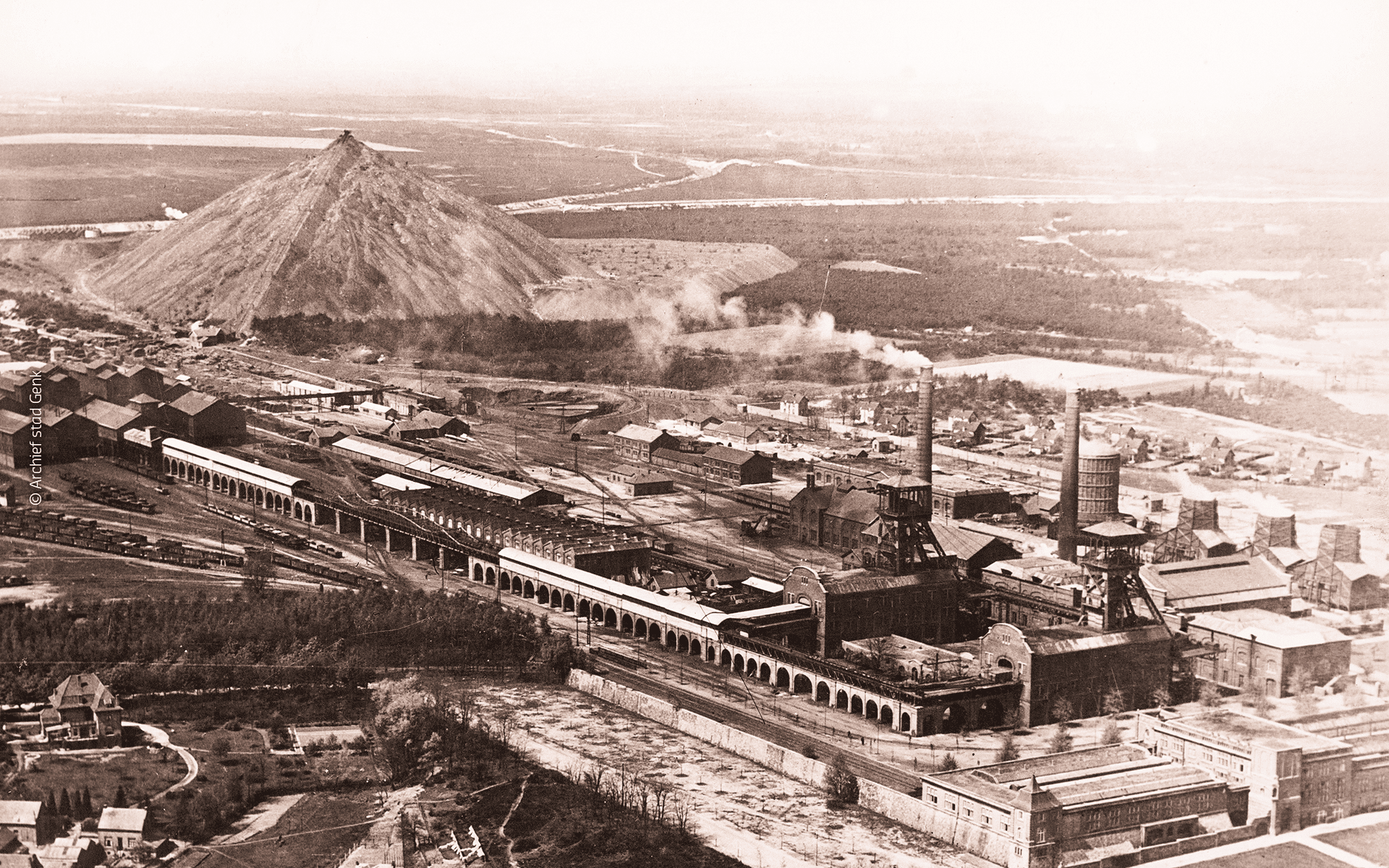

When at the beginning of the twentieth century, coal is discovered during an exploratory drilling in As near the then rural village of Genk, a total of seven mining sites were developed. In 1914 a miner extracts the first coal lump from the Kempen basin here. The much-coveted bituminous coal changes the landscape forever and Limburg soon becomes known as the El Dorado of Belgium.

The actual mining began in Winterslag in 1917. In addition to industrial buildings, the enormous mining site contains a fully developed underground concession that extends for miles. In 1988 production no longer proved to be profitable, the coal vein was exhausted, and the curtain fell on the mine exploitation in Winterslag.

The mining in Limburg began in Winterslag in 1917.

The mining in Limburg began in Winterslag in 1917.© Archives of the city of Genk

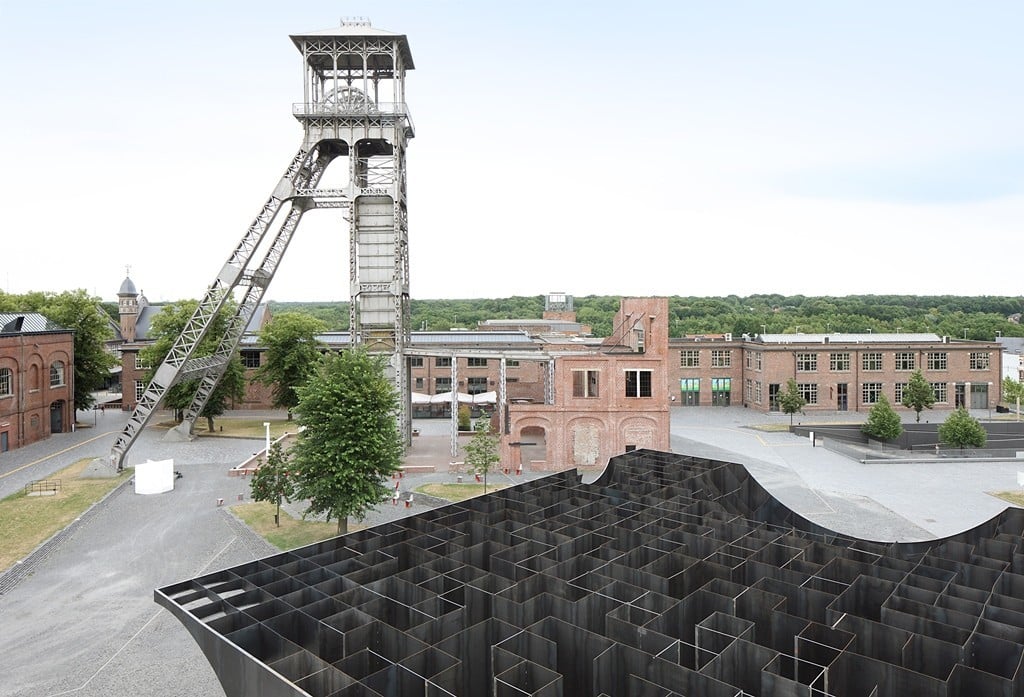

Now the site has been redesigned and can be visited as C-mine. This industrial heritage hotspot is more than a reminder of the underground past. Today Genk, which experienced a population explosion from 2,000 to more than 60,000 inhabitants in one generation due to labour migration, is a developing city. This creative hub, as C-mine likes to be called, plays an important role in this.

In addition to the C-mine Expedition mining museum, the rooms on the floor of the main building have space for temporary exhibitions of contemporary art and photography, as well as CIAP – Platform for Contemporary Arts and soon FLACC. The LUCA School of Arts is also housed in a sleek new building for the photography, audio-visual arts, and game design courses. But the eye-catchers of the spacious square are the high shaft towers that dominate this place.

The eye-catchers of the spacious square are the high shaft towers that dominate this place.

The eye-catchers of the spacious square are the high shaft towers that dominate this place.© C-mine

Underground History

You start the mining expedition in the large central hall of the prominent Energy Building. Above the reception area, the former compressor room and the fan building have been fully preserved in the robust and at the same time elegant architecture of the Belle Epoque, with wrought iron stairs and balustrades, indestructible tiled floors, and beautiful light. The old machine rooms with power plant and the extraction machines were restored and two new theatre rooms were harmoniously added to the existing buildings.

Inside the Energy Building.

Inside the Energy Building.© C-mine

But we descend, through the airways to a depth of six meters, where the history of the miners begins. Through the “white corridor” where the miners still cleanly started their shift, you walk to the cramped elevators and the corridor with flashes of light, which give an impression of the countless small explosions that were constantly taking place because of the rapidly igniting mine dust. In the interactive sound cell, you can manufacture your own mine “sound” by operating levers, buttons, and wheels. It must have been deafening and often nerve-racking for the mineworkers with the constant thumping, whistling, and rumbling in the narrow filthy tunnels.

© C-mine

In the story tubes, you will hear real-life testimonials from miners combined with animations, holograms, scale set construction and special effects. They are stories of migration, of camaraderie among miners, of missing family and loved ones, hard work, unhealthy working conditions. And at the same time the stories of the incomparable togetherness and the sense of community underground and in the shabby places where the coal miners lived, are touching indeed. The characteristic miner’s scarf, which has a practical use as well as symbolic and sentimental value, also plays a major role in this.

Guest workers

Following the two World Wars, the so-called Coal Battle ensues: there is a need for fuel and energy for the improving economy and growing steel industry. The demand for new workers is increasing and a bilateral agreement with Italy offers a solution: the first wave of guest workers comes to Belgium. However, after the mining disaster in Marcinelle in 1956, relations with Italy cooled. New miners are recruited in Spain, Greece, Turkey and Morocco.

The world comes together in the Limburg mining region. But the steep rise of the petroleum industry is crippling coal’s growth story. Out of a community reflex for fear of revolt in Wallonia, a Flemish mine was sacrificed in 1966: Zwartberg, the most modern and productive mine in Belgium at that time. The blow is enormous, the resistance great. Two miners are killed in the demonstrations that follow. Peace returns following the Zwartberg agreement: the mine will only close when everyone has found other employment.

One of the slag heaps in Limburg.

One of the slag heaps in Limburg.© C-mine

On 7 October 1966, the last coal wagon was hauled out of Zwartberg, and Winterslag also ground to a halt at the end of the 1980s. Between 1987 and 1992 all remaining mines in Belgium shut down. The heavy blow caused by the closures may have been got over, for the most part, today, but the economic consequences can still be felt in the old mining municipalities. This eventful history intertwined with the daily life of the miners can be very tangibly seen and heard in a clever animation via VR headset, while sitting in a tiny compartment of a narrow mine train.

New Purpose

Having just recovered from this submersion you then pass the black corridor above and re-emerge above ground, happy to see daylight again. Those who dare can lose themselves on the outside square in the impressive labyrinth of rust-coloured Cor-Ten steel, designed by architect duo Gijs Van Vaerenbergh. With its symmetry, more than man-sized plates in a geometric arrangement and structure that is difficult to unravel, there is something strange about the awe-inspiring maze. At the same time, it recalls the eerily oppressive tangle of tunnels underground, but in the open air. Once outside the children’s search continues for Cyriel de Krekel (Cyriel the Cricket) and his role in the mine.

Labyrinth of architect duo Gijs Van Vaerenbergh.

Labyrinth of architect duo Gijs Van Vaerenbergh.© Visit Limburg

The literal highlight of the expedition is the ascent of the authentic more than 60 meters high headframe on the square. This ingenious construction on top of the mine shaft was used to transport miners, material, and coal. The rotating wheels with a diameter of about eight meters have of course been shut down for years, but they form striking visual markings in the landscape. An intermediate stop on the unloading platform at a height of 15 m already gives you a broad view of the different facets of the life of coal mining.

The Winterslag mine building has been protected since 1993, but the coal laundry, brickyard, workshops, and cooling towers have not been preserved. All remaining protected monuments on the mining site were repurposed. Porcelain artist Pieter Stockmans, for example, turned the warehouse building into his studio and living space. The former horse stables serve as business space and C-mine Crib is situated in the old mining offices, an incubator for young, creative entrepreneurs. The former bath and lamp hall now houses a cinema complex, several companies and catering establishments.

At the start of their “post,” the miners went to collect their lamp and number from this lamp room, the “lampisterie” in miner’s lingo. Based on this number, it was always possible to check who was down in the mine at what time. Once back above ground, the miners showered in the large bathrooms. The milk bar was also located in this complex. After their shift, the miners could drink milk or chocolate milk for free. Milk increases mucus production so that mucus could be brought up. The miner also spewed the dust out of his respiratory tract with the phlegm.

One of the shaft towers on the former mining site in Winterslag.

One of the shaft towers on the former mining site in Winterslag.© Databank Publieke Ruimte

A magnificent view of the green Limburg surroundings awaits those climbing to the top of the shaft tower to brave the fierce wind. From here you can see the sites where the miners lived with their families. And the Vennestraat, Genk’s bustling trade artery where all languages and cultures (Italian, Polish, Turkish, Greek, Arabic…) that have flocked here since the 1950s are represented in a colourful mix.

Still further from the city, you can see the site of Labiomista to the north, where the former Zwartberg zoo used to be located. More to the south in the woods lies Bokrijk and beyond the rusting slag heaps of Waterschei and Beringen on the horizon, are remarkable hills in this otherwise flat landscape. Where narrow gauge railway cars used to dump the cinders and mine stone waste onto the growing heaps of stone, there are now windmills. The story of fossil fuels is clearly finite, that of coal virtually over. But in Limburg, it has decisively determined the landscape, the regional development and not least the population and its identity. C-mine knows how to keep that memory alive for the future.