Christophe Plantin Was a Cultural Entrepreneur Who Bound People With Books

Mainz 1450, Gutenberg developed MS-DOS. Antwerp 1550, Plantin introduced Windows. That is how the world’s first great communication revolution – the art of printing – feels today. Antwerp cannot claim to have invented printing, but Christophe Plantin (1520-1589) certainly re-invented the medium in the boomtown on the Scheldt. Five hundred years after his birth, publishers can still learn from his cultural entrepreneurship.

Johannes Wierix, portrait of Christophe Plantin, 1588

Johannes Wierix, portrait of Christophe Plantin, 1588© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

In Mainz, in 1450, the end of the Middle Ages, Gutenberg installed two wooden printing presses. It took him a year and a half to produce the first-ever printed book, a large-print Bible with neither decoration nor illustrations. One hundred and eighty copies, destined for churches and monasteries that had paid for them in advance. The remainder went to a market stall in Frankfurt, fifty kilometres away. The first de facto Frankfurt Book Fair. By then, though, Gutenberg was well and truly bankrupt.

In Antwerp, in 1550, the beginning of the modern age, Plantin installed twenty-two printing presses. There had never been such a large printing workshop before. Until then, even the most famous printers in Venice and Paris had worked with at the most four presses. At the height of his business, Plantin printed 25,000 books in a single year. Enough to be able to provide every head of a family in the metropolis of Antwerp with a book – or even every individual in a provincial city like Amsterdam, where 25,000 souls lived. In a single year.

Proto-industrial

With his proto-industrial workshop, Plantin had by that time been a pioneer of Europe’s multidisciplinary modern book trade for a quarter of a century. He had become increasingly clever at integrating illustrations into the texts. He had more and more deliberately introduced impressive typographic designs. He had steadily become more efficient at organising the textual content. And he experimented more and more daringly with price ranges, formats and print runs. A miniature book of hours as small as an eraser; a choral song book as big as a tabletop. Six hundred copies of a world-famous, beautifully illustrated anatomical atlas; thousands of shoddy almanacs with tugboat schedules and horoscopes on drab paper, outright pulp that served as toilet paper at the end of the year.

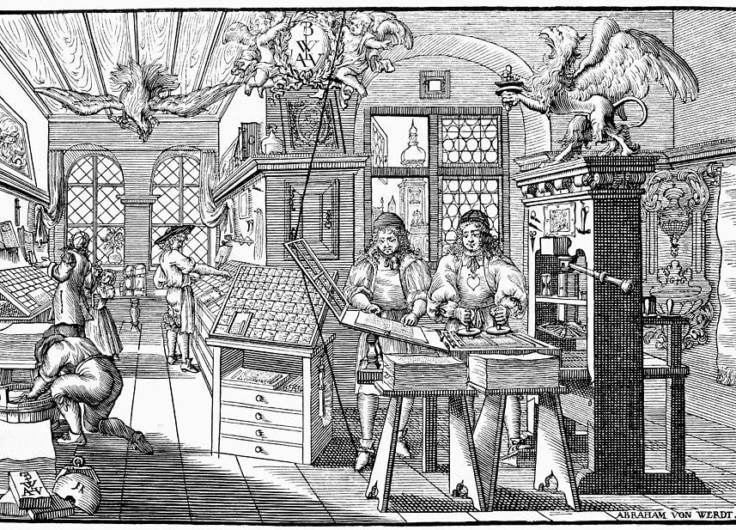

Plantin's two oldest preserved printing presses

Plantin's two oldest preserved printing presses© Museum Plantin-Moretus

In Antwerp alone, Plantin needed seven houses and a monastery to warehouse his stock, and his depot in Paris was overflowing with printed works. Books that he traded worldwide, carted off by the ton to the annual Frankfurt fair, shipped across the Scheldt by the bale to customers all over both the Old and the New World. His Hebrew Bible was on sale in Fes, Marrakech and Algiers. His Tridentine missal could be found on altars in Lima, Quito and Veracruz. His Polyglot Bible made its way into the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Plantin’s consolation

Looking back at the reception of my biography of Plantin, De woordenaar, it is striking that this portrait of his life turned out to be a consolation for today’s book producers. In this era of austerity in the cultural sector and competition from digital media, the book trade is struggling.

But, as his life story shows, it was difficult to survive in the book trade even in Plantin’s day. The sixteenth century may have been the heyday of book printing, but books were completely handmade and therefore relatively expensive. It was always uncertain whether people would want to buy such an expensive luxury item, and the consumer market was many times more unstable than nowadays due to war and print censorship. Yet Plantin showed future generations of publishers that a man could go a long way with hard work and a fervent conviction of the usefulness and necessity of the book trade. This particular printer managed to go almost or even completely bankrupt four times – after the persecution of heretics in 1562, the Iconoclasm in 1566, the Spanish Fury of 1576, and the Fall of Antwerp in 1585. But, again and again, Plantin managed to make a comeback.

Pulp and prestige

Of lasting historical significance is, first and foremost, that the tireless Plantin taught publishers in the trading metropolis of Antwerp to be cultural entrepreneurs. He ensured a guaranteed income thanks to a predictable supply, including calendars and almanacs. These were publications from which the publisher derived no professional pride. The fact that he produced tons of calendars and almanacs cannot even be established on the basis of the spectacular collection of books in his business archives. Because Plantin never kept this shoddy printed matter.

Two wooden boxes with letter stamps made for Plantin by Garamond and Granjon

Two wooden boxes with letter stamps made for Plantin by Garamond and Granjon© Plantin-Moretus Museum, Antwerp

By producing a varied collection designed for both the most well-fed piggy bank and the smallest purse, Plantin spread his risks. He could invest the profit from unpretentious printed matter, such as calendars and almanacs, in risky progressive publications – books with which he hoped to make a name for himself. For them he scouted the best editors, whom he provided with board and lodging, trained his own setters whom he paid well, and invested gold in typography and illustrative materials. It allowed Plantin to publish unique books that ensured that professional book readers kept coming back to him, even after his business had gone broke. These phenomenal printed works targeted at specialist readers required costly preparations. The clientele at whom the scientific and literary books were aimed was certainly able to put down large sums of money, but such clients were well-educated and discriminating, too. The prerequisite for lasting success was quality, and Plantin, the almanac printer, went for it uncompromisingly.

Addiction to buying

Plantin also taught publishers that cultural enterprise included careful consideration of books as objects. His love of letters and eye for form made him a trendsetter in the field of typographic and graphic design. At the same time, his extremely expensive letters and illustrations ensured that readers were no longer satisfied with the inferior graphic quality of other printers. Plantin changed book buyers from readers who were looking for content to book owners who were willingly to pay more for status-enhancing design. He acquired a following, too, for his library of classics. It was an ironclad collection of standard Latin and Greek authors in cleverly designed editions which, precisely because they were published in such a uniform way, bound customers. Plantin encouraged buyers to buy not only the books they wanted to read, but to purchase the books they needed to complete the impressive series they had in their bookcases, as well.

He understood that besides being carriers of information, books also conferred prestige. And he demonstrated how a demand for culture as a consumer item could be created among book buyers in a way that the people themselves had initially thought impossible. Not because this was his primary interest, but because he noticed that it sold.

Abraham Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. The first atlas ever was printed by Plantin in 1579

Abraham Ortelius' Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. The first atlas ever was printed by Plantin in 1579© World Digital Library

Subversive voices

Gutenberg printed exclusively for religious institutions. Churches and monasteries were regarded as reliable customers that were rolling in money. In the trading metropolis of Antwerp, however, Plantin printed not only for secular and religious institutions – the structures of power – but for town and country people as well. Plantin did not work with the certainty of institutional subscription lists and bureaucratic advance payments. He was a trade capitalist, so he produced a supply and created the demand himself.

For a commercial printer to be successful in business and create new demand, he had to have an unfailing sense of what was going on in society. Plantin was a master in this respect, surpassing other publishers. He knew very well what was at issue in science and literature. He knew exactly what was missing at school and university. And he knew better than anyone the preoccupations of the middle classes. That is why he developed schoolbooks in the vernacular and the very first vernacular dictionaries for schoolchildren and teachers.

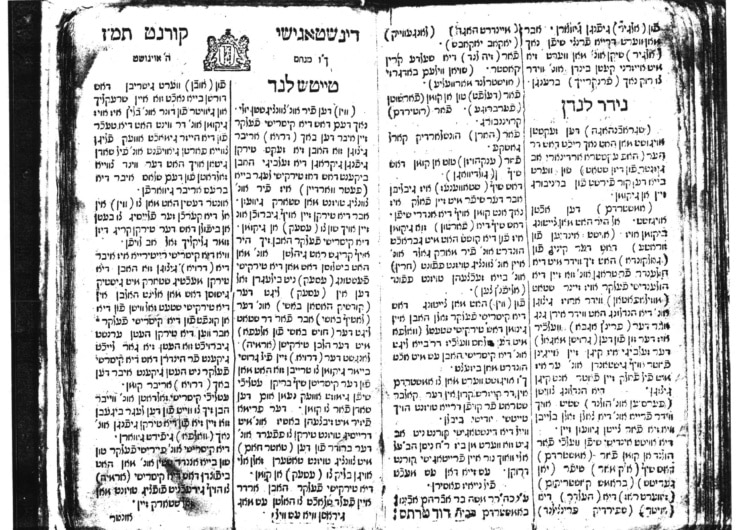

He printed books for both dominant and minority religious communities

In this way he promoted literacy and literature in the language of the people – and enlarged his market in the process. He printed religious books for Catholics and Calvinists, Anabaptists and Jews, thereby providing for the most burning reading needs of both dominant and minority religious communities. It was a guaranteed gold mine. If necessary, people were prepared to eat less to buy a Bible. Sometimes his printed matter was normative and sometimes it was subversive. It did not matter to Plantin. The pursuit of profit makes people deaf and blind – which at least provides a podium for subversive voices.

Binding with books

The great thing about Plantin’s cultural entrepreneurship was that he invested an incredible amount of time and money in putting his personal intellectual preferences on the agenda. In doing so he proved himself to be a socially engaged man who, as a publisher, wanted to professionally articulate his concerns about the increasing violence in the society in which he lived. He tried to intervene in the greatest problems of his time – the social and cultural divisions in the Netherlands and the intolerant religious policies of the country’s government, which was heading for religious war.

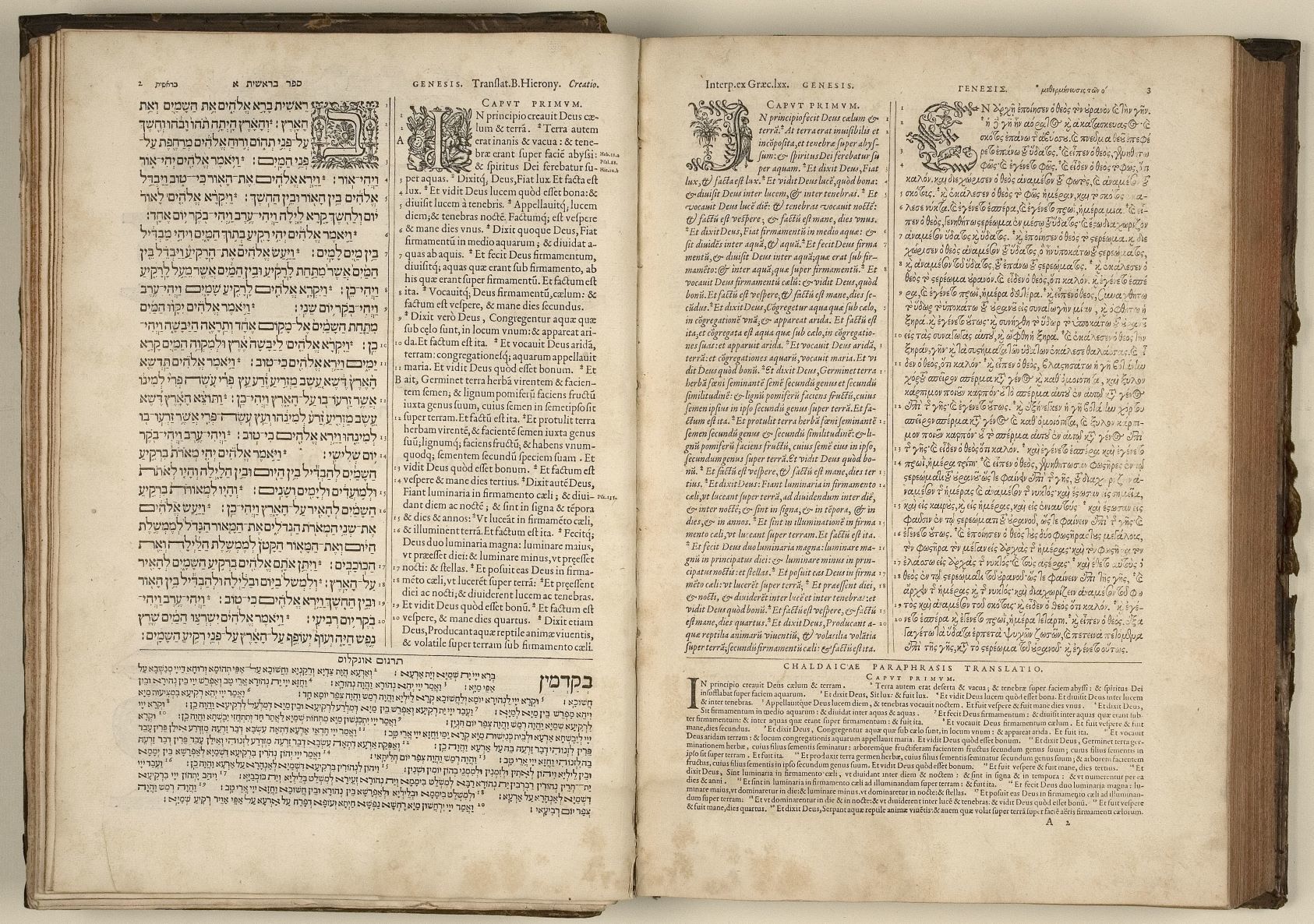

The Polyglot Bible, printed by Plantin

The Polyglot Bible, printed by PlantinIn an age of polarization, Plantin hoped to bind people with books. He produced study Bibles that advised religious dialogue and dictionaries that propagated a unified language. Plantin stuck his neck out with his Polyglot Bible, for which he had hired editors suspected of heresy, to then have King Philip II send an inquisitor after him. The publisher was prepared to crawl for Philip in order to be able to print the Polyglot Bible. Ultimately, cultural entrepreneurship was personal and political. Plantin showed book publishers that.

A very human hero

The situation in the book trade has not improved since De woordenaar was published. To what extent exactly does Plantin’s story offer us consolation, as we read in the reviews of De woordenaar? Obviously book producers from every era could derive strength from his heroic dedication to books. Everyone needs heroes, so yes, absolutely, let Plantin be the hero of all book publishers. The consolation lies in the recognisable humanity of his struggle to survive professionally, which was sometimes ugly and as opportunistic as could be.

Everything of value is defenceless, now and in every century. The consolation does not come from Plantin’s success. The consolation lies in his lifelong determination to continue making good products regardless of the obstacles. Only saints never end up at the crossroads where souls are sold to the devil. Let us just say that Plantin sold his for the highest possible price.

The cost of success

Plantin lived in the sixteenth century, a very different time from ours. The real hard core of his survival strategy cannot be repeated by modern book producers. In the metropolis of Antwerp, Plantin, as a capitalist tradesman, overshadowed all his competitors by blatantly enriching himself, while at the same time exploiting to the maximum his opportunity to inform people and educate them. The craft trades would never be the same after Plantin.

Inside Museum Plantin-Moretus

Inside Museum Plantin-Moretus© Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp

It is striking that generations of printers before Plantin stuck religiously to the medieval guild regulations pertaining to the older crafts, which structurally discouraged production growth and increased profit. As entrepreneurial organisations, the guilds took great care to ensure that only an extremely limited number of new master craftsmen were allowed to start a business. Every master craftsman was obliged to employ as few assistants as possible, to keep the supply small, the quality high and the prices stable. This meant that every workshop could be guaranteed a solid market and all the workers always had enough to live on. Within this safely regulated world, printing workshops actually produced to order rather than for the free market.

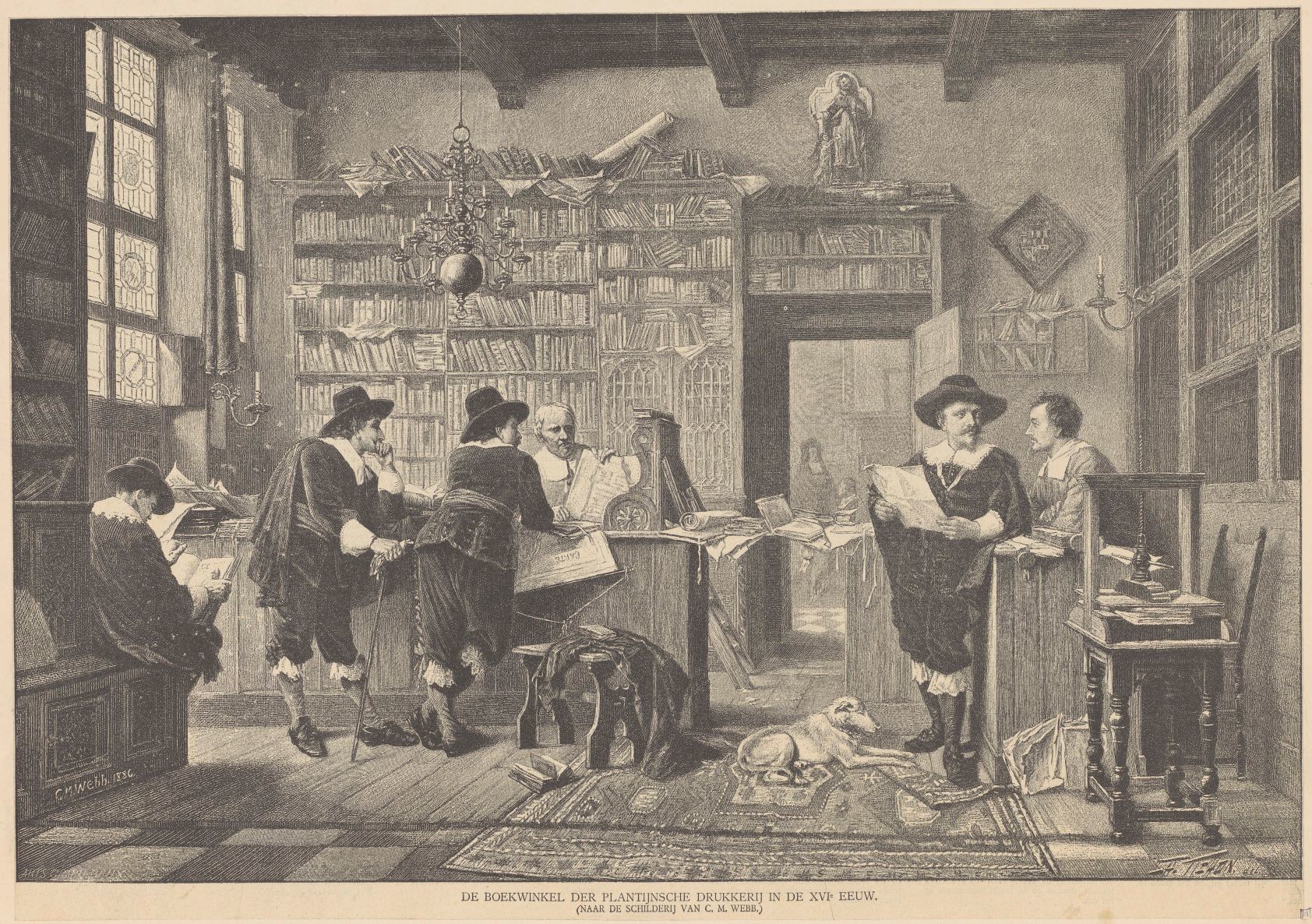

The bookshop of Plantin

The bookshop of PlantinPlantin flouted all the medieval guild’s regulations. He installed as many presses as he could and hired dozens of people. Men with families, whom he put back out on the streets with the same lack of scruples when, in times of economic malaise, cuts had to be made in the business. The cost of success is always paid by the weakest party. The survival of his family firm was, understandably enough, the publisher’s number-one priority. His business had to maintain a wife, five daughters, five sons-in-law and twenty-two grandchildren. In difficult times it was his employees, who were not protected by social legislation, who had to foot the bill for all of this. And his authors as well for that matter. Because there was no copyright in the sixteenth century, so publishers were not obliged to pay writers for the books they sold.

Epilogue

Vantilt publishing house

Vantilt publishing houseWhile this contribution was being written, with a view to the celebrations for Plantin in Antwerp, yet another small, quality publisher closed its doors in the Netherlands. For a quarter of a century, Vantilt was an independent publishing house for non-fiction works. Plantin would have revelled in the cultural entrepreneurship underlying Vantilt’s most masterly publication, 1001 vrouwen (1001 Women), a scrupulously researched reference book of women’s history, edited by historian Els Kloek and designed by graphic designer Irma Boom. Cleverly, this extraordinarily socially engaged book appeals to two very different groups of cultural consumers – people who buy books and people who buy art. Recently, it was voted Best History Book of All Time.

Yet the publisher declared that the relatively high overhead costs of a small publishing company are no longer affordable, partly because the market for textbooks and dissertations – Vantilt’s equivalent of the almanacs – has collapsed, as a result of the anglicization of Dutch universities. It takes less than a Spanish Fury to put a stop to vulnerable modern publishing.