Colonial Echoes. When Americans Spoke Dutch

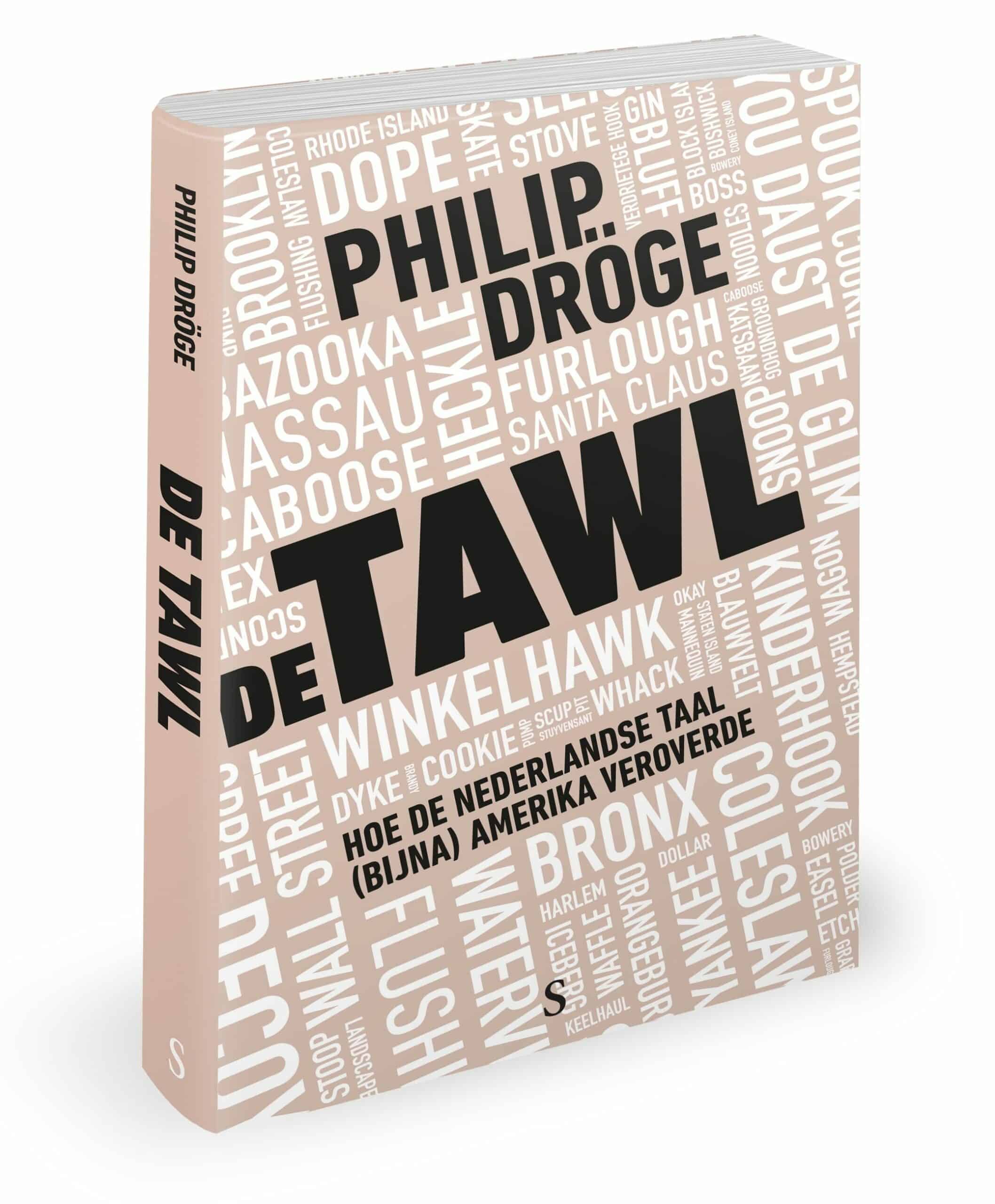

It is well-known that New York was once called New Amsterdam. But who knows that for centuries, a variant of the Dutch language was spoken in the eastern American states of New York and New Jersey? In his book ‘De Tawl’, historian Philip Dröge cycles along American roads in search of what remains of that Dutch-speaking past today.

The history of the Dutch language in America is a fascinating topic and the author takes two approaches to learning about it. First, and primarily, the book is a travelogue of a biking trip Dröge made in New York and New Jersey, to learn more about the influence of the Dutch language in the region. The bicycle trip, the scenery, and the people and places Dröge encounters are well-described. However, what Dröge discovers about the Dutch language in the region is superficial, and I mean literally superficial: some street and city names, text on a few old tombstones, bits of Dutch on paper in museums. In fact, one might suspect this book is deep satire, and if so, it is genius. The satirical element is that every time Dröge asks a New Yorker about anything related to the Dutch, he is met with a blank stare. Nobody speaks it, nobody knows much about it. When Dröge writes “What am I actually looking for here, I ask myself at every steep metre,” I ask myself the same thing. What is he looking for?

Map of New Amsterdam in 1660 showing the wall, from which Wall Street is named

Map of New Amsterdam in 1660 showing the wall, from which Wall Street is named© Researchgate.net

Because he finds so little of the Dutch language on the ground, Dröge must rely on discussions with historians, an archaeologist, and his reading of secondary sources to fill in the story. No primary source research went into this, so to a historian of the Dutch in New York, there is nothing new here. But as a light summary of the existing research, it is fairly up to date and inclusive. There is an important place in historical writing for both scholars who create new knowledge and popularizers who take narrowly-known subjects and make them accessible and interesting to general readers. And, as far as I am aware, this is the first non-academic book about the colonial Dutch American language written in Dutch.

Of the 76,000 enslaved people who ever set foot in New York in the eighteenth century, 30 to 40 per cent could speak Dutch

Crucially, Dröge notes that “De Tawl” was a multi-ethnic language. Not only did the Germans, Scandinavians, Jews, and Africans who lived in New Amsterdam learn Dutch, but Native Americans, English settlers, and enslaved Africans in the Hudson Valley in the 17th and 18th century also learned a smattering of Dutch, as it was the main language of trade in the region, with Albany as a center. Dröge suggests that there is no way to know how many African Americans spoke Dutch, but I have recently made such an estimate in a peer-reviewed article: of the 76,000 enslaved people who ever set foot in New York in the eighteenth century, 30 to 40 per cent could speak Dutch, i.e. 22,800 to 30,000 people.

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883), one of the icons of America’s Black Liberation Movement, was a native speaker of Dutch.

Sojourner Truth (c. 1797-1883), one of the icons of America’s Black Liberation Movement, was a native speaker of Dutch.© National Portrait Gallery, Washington

Dröge also highlights an aspect of the language decline that is often overlooked: that the Dutch language in New York dissipated last in the Mohawk Valley, while residents from there moved west. He notes further that the Dutch language was old-fashioned and mocked in the United States by the 1830s. Historians of the current generation have emphasized that the Dutch language did hold on in New York and New Jersey longer than previously thought. Nowhere in the scholarship, however, have I come across the claim that in New York City, upon the adoption of English as the sole language of instruction in 1758, were children punished if they spoke a word of Dutch. That Dröge does not cite a source for this claim makes me question it all the more. He reinforces this point a few pages later when he writes of “strict schoolteachers.” Of course, our stereotype of teachers in the past is that they were all strict, but that is not necessarily so.

Probably the most common label for the Netherlandic dialect in New York and New Jersey was 'Low Dutch' or 'Leeg Duits'

I am also not convinced that the pronunciation of “Taal” in colonial New York was “Tawl.” This does, however, serve as a convenient description for a language that has been described in various ways, but never properly labeled. Probably the most common label for it has been “Low Dutch” or “Leeg Duits,” which was often used to distinguish the Netherlandic dialect in New York and New Jersey from the German American tongue. Like any language, this one evolved over time, and gradually developed its own distinct pronunciations and spellings, while incorporating many loan words from English, French, Spanish, and native American languages, that would distinguish it from the Dutch spoken in the Netherlands. The language likely also had regional differences, with variations developing separately in New Jersey, Long Island, and the upper Hudson Valley.

Dröge does not mention the new waves of Dutch immigrants that came to New Jersey and New York from the 1850s through World War One. These Dutch are an important, albeit complicating part of the story. They make the story difficult because the few remnants of the colonial Dutch language in the region died away while the new immigrant language took its place, often leading to confusion in the historical record about when and where colonial Dutch was last spoken.

A home for Dutch sailors and immigrants in Hoboken, New Jersey, c. 1920-1930

A home for Dutch sailors and immigrants in Hoboken, New Jersey, c. 1920-1930© Calvin University

Dröge also invents the term “Neder-Amerikanen” to describe his subjects. Scholars have never used this term, but they don’t have much better options, because neither “colonial Dutch,” “Low Dutch,” “Dutch-Americans,” or “Anglo-Dutch,” perfectly capture the group of Dutch speakers in New York and New Jersey from the 17th through 19th centuries.

Dröge often adds a moralistic comment to the story. He treats the success of the Dutch in New York as coming at the expense of Native Americans. He calls it “The classic story of European colonies: progress at the expense of other peoples.” A few pages later, speaking of the presence of Dutch churches in the area, he says “None of the Christians wanted to turn the other cheek to the Indians.” Surely this is hyperbole, the history of Christians and Native Americans is more nuanced.

Dröge invents the term 'Neder-Amerikanen' to describe his subjects. Scholars have never used this term, but they don’t have much better options

Stereotypes of Americans past and present also feature in the work. “Americans are generally proud of where they live,” he writes, “but they often know remarkably little about it.” The churchgoers in Katsbaan, New York, he adds, know little of their Dutch history. And “I have to stop watching Fox News in the motels where I stay overnight, where the constant shootings in the United States are widely reported.”

He is not the first one to notice that the new generation of pick-up trucks are more for show than for work, nor that the state building in Albany looks like it was built in North Korea. Dröge, at times, over-romanticizes his subject. Writing about the Dutch in New Jersey in the mid-twentieth century, he states that little had changed in centuries, and that “everything mainly remained as it was.” That is quite an exaggeration. He accepts the origin story of the word “O.K.” rooted in the campaign of presidential candidate Martin Van Buren, “Old Kinderhook.” The veracity of that story is, however, up for debate.

Despite the subtitle of the book, the Dutch language did not almost take over America. In fact, far from it. The language was marginal compared to German, French, or Spanish. It has been common for decades now to use inaccurate book titles to encourage sales. This is unfortunate. But, the strange thing here is that the book does not even try to argue that the Dutch language almost took over America. It does, however, provide a readable overview of what scholars generally know about the language, without being overly encumbered by linguistics or historiographical debate.

Philip Dröge, De Tawl. Hoe de Nederlandse taal (bijna) Amerika veroverde, Spectrum, Amsterdam, 2023, 256 pages